This is part one of a five-part essay that highlights lessons from the coronavirus pandemic which could advance the fight for a Green New Deal. Part one argues that money is not scarce. Part two argues that control of government policy by wealthy elites tends to produce unnecessary suffering and inadequate responses to major crises. Part three argues that plutocracy is incompatible with serious climate action. Part four explores how the public can easily draw very different conclusions and argues that the climate movement must undertake mass education to ensure these lessons are learned. Part five outlines a broad curriculum containing these lessons and many more.

Introduction

Over the past year there has been much discussion about what we can learn from the coronavirus pandemic, and for good reason: the lessons instilled in its wake could dramatically change the course of society. Perhaps the most crucial insights are those that could help us steer away from the persistent existential threats we face. For the climate crisis in particular—which demands a societal reboot—the stakes could not be higher.

If certain lessons highlighted by our experience with the pandemic are internalized by the climate movement and much of the general public, we will be far better prepared for the fight to enact a Green New Deal. This essay identifies three of them, with each building on the previous one.

The first lesson is that money is not scarce. The federal government has created trillions of dollars for pandemic relief, dispelling myths about financial constraints that make progressive policies seem unaffordable.

The second lesson is that our society’s economic and political systems, as currently constructed, routinely cause unnecessary suffering. In particular, the pandemic illustrates how wealthy elites’ control over public policy tends to suppress government spending and produce an inadequate response to major crises. Fundamental system change is necessary.

The third lesson is that plutocracy is incompatible with addressing climate change. If the government is willing to reopen the economy in the midst of a growing plague to placate business interests, there’s little chance of reducing emissions at the steep rates that science prescribes, because doing so very likely requires the curtailment of some economic activity. We’ll need truly democratic governance to enact transformative climate policies.

The prospects for implementing a Green New Deal rest on the emergence of a new and enduring political common sense. However, the public can easily draw different conclusions about the response to the pandemic that perpetuate existing political narratives, fueling apathy or resistance to change. This essay argues that the climate movement must take on the task of mass education if the right lessons are to be learned. It concludes by outlining a broad curriculum containing these lessons and many more.

Lesson 1: Money Is Not Scarce

As the $2.2 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act was being prepared in March 2020, economist and Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) expert Stephanie Kelton began making her rounds in both agenda-setting and activist-oriented media outlets. She was trying to spotlight the fact that politicians had thrown out the question posed most often in discussions about public policy: how will you pay for it?

That question is perhaps the greatest intellectual weapon against progressive policies, and its power stems from everyday people not knowing the process behind government spending and what the real limits are. Most think that governments can only spend after collecting taxes, but that is only true for the ones that don’t issue their own currency (such as city, state, or certain foreign governments). The US federal government, as the issuer of the US dollar, doesn’t need to tax first before it can spend. It just creates new money out of thin air.

Kelton describes the very simple process: first, Congress passes a bill that authorizes spending on some priority issue and sends payment instructions to our central bank, the Federal Reserve. The Fed then creates new money with a few taps on a computer keyboard—“digital dollars” that are added to the bank accounts of every group paid by the bill. This happens every day as the government purchases things. That’s it.

The persistent myth has been that the federal government cannot spend on something new without raising taxes or cutting spending elsewhere. “Paying for” a new policy means combining the injection of new money into the economy with measures to remove an equal amount. Spending without simultaneously cutting back results in a budget deficit, and according to the myth, deficit spending will always lead to ever-rising prices and a collapsing economy.

However, massive deficit spending during the Great Recession did not lead to major inflation and neither has the new money created for pandemic relief, just 12 years later. Before 2008, big deficits had been run up for congressional priorities like waging war or cutting taxes for the wealthy—priorities never subject to the “how will you pay for it” question—without leading to an inflation crisis. But it’s these multi-trillion-dollar bailout events that are demonstrating as clearly as possible that increasing deficits are not inherently inflationary.

This doesn’t mean that there are no limits. The constraints on creating new money are set by the productive capacity of the economy. If so much money starts circulating through the economy that it greatly exceeds the amount of goods and services available for purchase, then inflation will occur. But if output can be increased, then new money can be absorbed without changing prices. It is after things are running at full capacity that continued increases in the money supply can generate inflation.

How close are we to that point? We don’t exactly know until we hit it. Economies emerging from a recession have plenty of unused capacity for production, with no real threat of inflation on the horizon. Also, if prices really started to rise, we know how to resolve the problem. The government can simply raise taxes or cut spending on lower priorities, like waging war, to remove money from circulation—even making these responses kick in automatically if prices were to accelerate.

The point is that government spending seems to have been kept artificially low through fearmongering about deficits and imminent inflation. We are seeing that it is possible to spend without simultaneously raising taxes or cutting spending elsewhere. It is this commitment to “paying for” all new spending that has tended to leave progressive policies dead on arrival, because few in Congress are willing to face political battles over the money-draining measures. Some new policies that serve public interests aren’t large enough to cause inflation and could simply be implemented without removing any money from circulation. And for large-scale programs needed immediately, like a Green New Deal, we could pass them first and rein in spending later if inflation becomes an issue. The real-world demonstration of increasing deficits without inflation means we should be spending more to meet public needs. Money is not scarce, and activists cannot ask for clearer evidence than what we see unfolding before our eyes.

There are two significant caveats here. First, there is a difference between the amount of spending that is possible with the current high-consumption economy and the one we must build. Humanity is experiencing ecological overshoot—a series of crises, including climate change, arising from overwhelming human demands on this finite planet. Addressing these issues requires wealthy nations to consume less. Making our society sustainable entails a process that would deliberately reduce the productive capacity of the economy, which would constrain the amount we can spend before experiencing inflation. Though spending doesn’t seem to face major constraints today, this may become more of an issue during and after the transition, and should figure into activists’ planning.

The second caveat, which follows from the first, is that MMT doesn’t eliminate the need for cultural change. It simply delays a reckoning with fiscal limits, as the ceiling for government spending is set according to inflation rather than arbitrary deficit figures. At some point we will likely need to remove money from circulation. Before that need arises, activists must cultivate wide recognition that it’s legitimate to cut the military budget, reduce the wealth of the superrich, and also scale back the consumption of the majority or redirect it from individual assets (like personal vehicles) to collective ones (like expanded public transit).

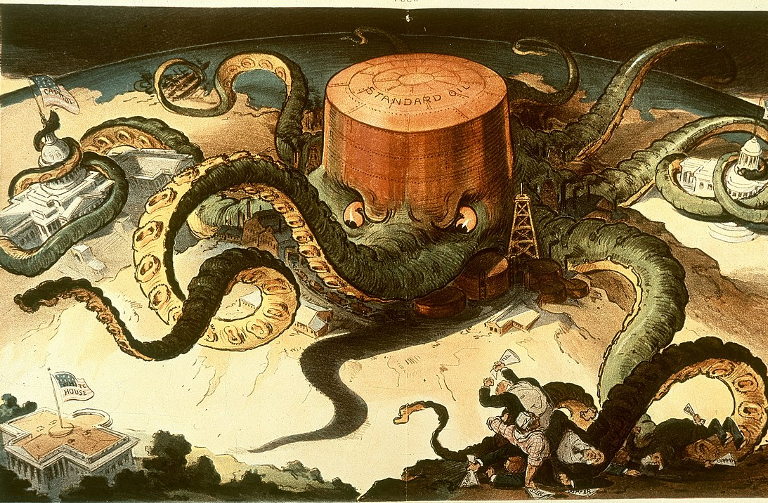

Teaser photo credit: Contemporary nineteenth century depiction of an acquistive and manipulative business enterprise as an all-powerful octopus. Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=530376