Social media has been ablaze with this question recently. We know we face a crisis of mass poverty: the global economy is organized in such a way that nearly 60% of humanity is left unable to meet basic needs. But the question at stake this time is different. A couple of economists on Twitter have claimed that the world average income is $16 per day (PPP). This, they say, is proof that the world is poor in a much more general sense: there is not enough for everyone to live well, and the only way to solve this problem is to press on the accelerator of aggregate economic growth.

This narrative is, however, hobbled by several empirical problems.

1. $16 per day is not accurate

First, let me address the $16/day claim on its own terms. This is a significant underestimate of world average income. The main problem is that it relies on household surveys, mostly from Povcal. These surveys are indispensable for telling us about the income and consumption of poor and ordinary households, but they do not capture top incomes, and are not designed to do so. In fact, Povcal surveys are not even really legitimate for capturing the income of “normal” high-income households. Using this method gives us a total world household income of about $43 trillion (PPP). But we know that total world GDP is $137 trillion (PPP). So, about two-thirds of global income is unaccounted for.

What explains this discrepancy? Some of the “missing” income is the income of the global rich. Some of it is consumption that’s related to housing, NGOs, care homes, boarding schools, etc, which are also not captured by these surveys (but which are counted as household consumption in national accounts). The rest of it is various forms of public expenditure and public provisioning.

This final point raises a problem that’s worth addressing. The survey-based method mixes income- and consumption-based data. Specifically, it counts non-income consumption in poor countries (including from commons and certain kinds of public provisioning), but does not count non-income consumption or public provisioning in richer countries. This is not a small thing. Consider people in Finland who are able to access world-class healthcare and higher education for free, or Singaporeans who live in high-end public housing that’s heavily subsidized by the government. The income equivalent of this consumption is very high (consider that in the US, for instance, people would have to pay out of pocket for it), and yet it is not captured by these surveys. It just vanishes.

Of course, not all government expenditure ends up as beneficial public provisioning. A lot of it goes to wars, arms, fossil fuel subsidies and so on. But that can be changed. There’s no reason that GDP spent on wars could not be spent on healthcare, education, wages and housing instead.

For these reasons, when assessing the question of whether the world is poor in terms of income, it makes more sense to use world average GDP, which is $17,800 per capita (PPP). Note that this is roughly consistent with the World Bank’s definition of a “high-income” country. It is also well in excess of what is required for high levels of human development. According to the UNDP, some nations score “very high” (0.8 or above) on the life expectancy index with as little as $3,300 per capita, and “very high” on the education index with as little as $8,700 per capita. In other words, the world is not poor, in aggregate. Rather, income is badly maldistributed.

To get a sense for just how badly it is maldistributed, consider that the richest 1% alone capture nearly 25% of world GDP, according to the World Inequality Database. That’s more than the GDP of 169 countries combined, including Norway, Argentina, all of the Middle East and the entire continent of Africa. If income was shared more fairly (i.e., if more of it went to the workers who actually produce it), and invested in universal public goods, we could end global poverty many times over and close the health and education gap permanently.

2. GDP accounting does not reflect economic value

But even GDP accounting is not adequate to the task of determining whether or not the world is poor. The reason is because GDP is not an accurate reflection of value; rather, it is a reflection of prices, and prices are an artefact of power relations in political economy. We know this from feminist economists, who point out that labour and resources mobilized for domestic reproduction, primarily by women, is priced at zero, and therefore “valued” at zero in national accounts, even though it is in reality essential to our civilization. We also know this from literature on unequal exchange, which points out that capital leverages geopolitical and commercial monopolies to artificially depress or “cheapen” the prices of labour in the global South to below the level of subsistence.

Let me illustrate this latter point with an example. Beginning in the 1980s, the World Bank and IMF (which are controlled primarily by the US and G7), imposed structural adjustment programmes across the global South, which significantly depressed wages and commodity prices (cutting them in half) and reorganized Southern economies around exports to the North. The goal was to restore Northern access to the cheap labour and resources they had enjoyed during the colonial era. It worked: during the 1980s the quantity of commodities that the South exported to the North increased, and yet their total revenues on this trade (i.e., the GDP they received for it) declined. In other words, by depressing the costs of Southern labour and commodities, the North is able to appropriate a significant quantity effectively for free.

The economist Samir Amin described this as “hidden value”. David Clelland calls it “dark value” – in other words, value that is not visible at all in national or corporate accounts. Just as the value of female domestic labour is “hidden” from view, so too are the labour and commodities that are net appropriated from the global South. In both cases, prices do not reflect value. Clelland estimates that the real value of an iPad, for example, is many times higher than its market price, because so much of the Southern labour that goes into producing it is underpaid or even entirely unpaid. John Smith points out that, as a result, GDP is an illusion that systematically underestimates real value.

There is a broader fact worth pointing to here. The whole purpose of capitalism is to appropriate surplus value, which by its very nature requires depressing the prices of inputs to a level below the value that capital actually derives from them. We can see this clearly in the way that nature is priced at zero, or close to zero (consider deforestation, strip mining, or emissions), despite the fact that all production ultimately derives from nature. So the question is, why should we use prices as a reflection of global value when we know that, under capitalism, prices by their very definition do not reflect value?

We can take this observation a step further. To the extent that capitalism relies on cheapening the prices of labour and other inputs, and to the extent that GDP represents these artificially low prices, GDP growth will never eradicate scarcity because in the process of growth scarcity is constantly imposed anew.

So, if GDP is not an accurate measure of the value of the global economy, how can we get around this problem? One way is to try to calculate the value of hidden labour and resources. There have been many such attempts. In 1995, the UN estimated that unpaid household labour, if compensated, would earn $16 trillion in that year. More recent estimates have put it at many times higher than that. Similar attempts have been made to value “ecosystem services”, and they arrive at numbers that exceed world GDP. These exercises are useful in illustrating the scale of hidden value, but they bump up against a problem. Capitalism works precisely because it does not pay for domestic labour and ecosystem services (it takes these things for free). So imagining a system in which these things are paid requires us to imagine a totally different kind of economy (with a significant increase in the money supply and a significant increase in the price of labour and resources), and in such an economy money would have a radically different value. These figures, while revealing, compare apples and oranges.

3. What matters is resources and provisioning

There is another approach we can use, which is to look at the scale of the useful resources that are mobilized by the global economy. This is preferable, because resources are real and tangible and can be accurately counted. Right now, the world economy uses 100 billion tons of resources per year (i.e., materials processed into tangible goods, buildings and infrastructure). That’s about 13 tons per person on average, but it is highly unequal: in low and lower-middle income countries it’s about 2 tons, and in high-income countries it’s a staggering 28 tons. Research in industrial ecology indicates that high standards of well-being can be achieved with about 6-8 tons per per person. In other words, the global economy presently uses twice as much resources as would be required to deliver good lives for all.

We see the same thing when it comes to energy. The world economy presently uses 400 EJ of energy per year, or 53 GJ per person on average (again, highly unequal between North and South). Recent research shows that we could deliver high standards of welfare for all, with universal healthcare, education, housing, transportation, computing etc, with as little as 15 GJ per capita. Even if we raise that figure by 75% to be generous it still amounts to a global total of only 26 GJ. In other words, we presently use more than double the energy that is required to deliver good lives for everyone.

When we look at the world in terms of real resources and energy (i.e., the stuff of provisioning), it becomes clear that there is no scarcity at all. The problem isn’t that there’s not enough, the problem, again, is that it is maldistributed. A huge chunk of global commodity production is totally irrelevant to human needs and well-being. Consider all the resources and energy that are mobilized for the sake of fast fashion, throwaway gadgets, single-use stadiums, SUVs, bottled water, cruise ships and the military-industrial complex. Consider the scale of needless consumption that is stimulated by manipulative advertising schemes, or enforced by planned obsolescence. Consider the quantity of private cars that people have been forced to buy because the fossil fuel industry and automobile manufactures have lobbied so aggressively against public transportation. Consider that the beef industry alone uses nearly 60% of the world’s agricultural land, to produce only 2% of global calories.

There is no scarcity. Rather, the world’s resources and energy are appropriated (disproportionately from the global South) in order to service the interests of capital and affluent consumers (disproportionately in the global North). We can state it more clearly: our economic system is not designed to meet human needs; it is designed to facilitate capital accumulation. And in order to do so, it imposes brutal scarcity on the majority of people, and cheapens human and nonhuman life. It is irrational to believe that simply “growing” such an economy, in aggregate, will somehow magically achieve the social outcomes we want.

We can think of this in terms of labour, too. Consider the labour that is rendered by young women in Bangladeshi sweatshops to produce fast fashion for Northern consumption; and consider the labour rendered by Congolese miners to dig up coltan for smartphones that are designed to be tossed every two years. This is an extraordinary waste of human lives. Why? So that Zara and Apple can post extraordinary profits.

Now imagine what the world would be like if all that labour, resources and energy was mobilized instead around meeting human needs and improving well-being (i.e., use-value rather than exchange-value). What if instead of appropriating labour and resources for fast fashion and Alexa devices it was mobilized around providing universal healthcare, education, public transportation, social housing, organic food, water, energy, internet and computing for all? We could live in a highly educated, technologically advanced society with zero poverty and zero hunger, all with significantly less resources and energy than we presently use. In other words we could not only achieve our social goals, but we could meet our ecological goals too, reducing excess resource use in rich countries to bring them back within planetary boundaries, while increasing resource use in the South to meet human needs.

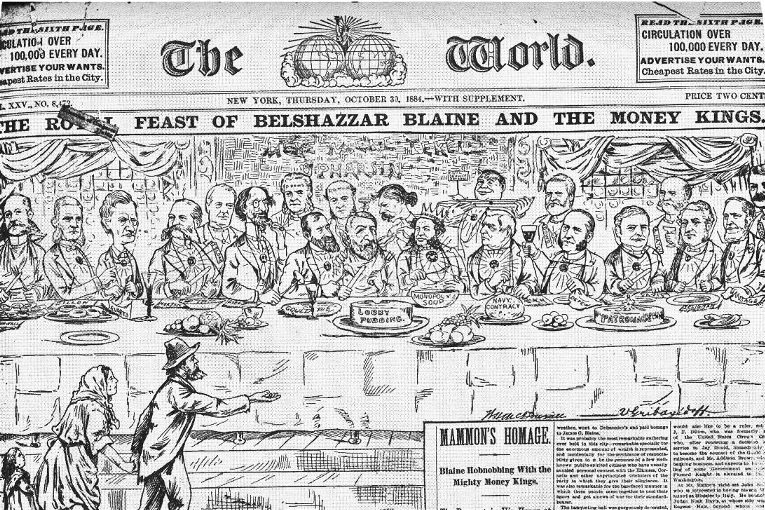

There is no reason we cannot build such a society (and it is achievable, with concrete policy, as I describe here, here and here), except for the fact that those who benefit so prodigiously from the status quo do everything in their power to prevent it.

Teaser photo credit: By Walt McDougall – Originally printed in New York World, October 30, 1884.Reprinted: Belshazzar Blaine and the Money Kings. HarpWeek. HarpWeek, LLC., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=48322037