Last year will be remembered for many things, and let’s be honest: most of them will be bad. But amidst the hardship and suffering, there is a positive story to be told.

2020 was perhaps the first time in living memory when governments around the world took radical action to put the interests of public health and wellbeing above that of private profit. For a world that is so dominated by the logic of capitalism, that’s no small triumph.

It’s tempting to say that this was a one-off response to a one-off pandemic. But this is to misunderstand both the nature of COVID-19 and global capitalism. If you hoped we could leave life or death political decisions behind us in 2020, then I’m here to disappoint. Because in 2021, the stakes are even higher.

First, some context. Before COVID-19 gripped the world’s attention, humanity’s primary challenge was clear: our fossil fuel-based economic system had pushed our natural environment beyond safe operating zones, threatening the foundations upon which civilisation depends. Without “rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society” we were on track to experience devastating and irreversible damage to our climate and ecological systems, and the end of life as we know it.

In recognition of this stark reality, in 2015 world leaders signed the Paris Agreement which aimed to limit global warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels. Achieving this would require a global mobilisation of resources on an unprecedented scale to rapidly cut emissions.

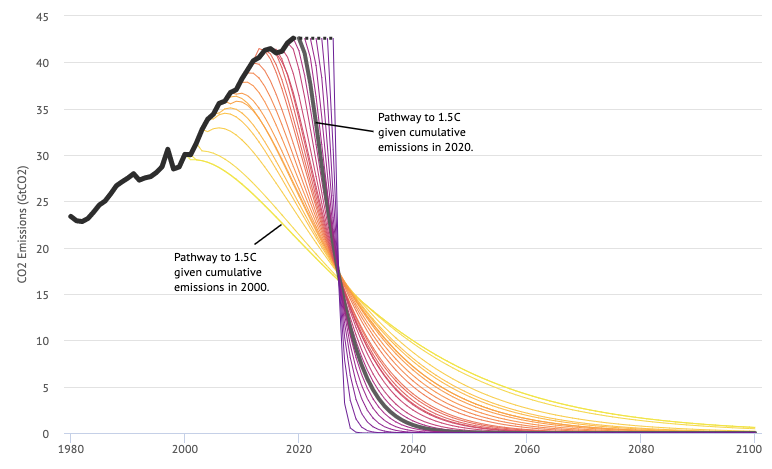

Although impressive on paper, for the most part this was not matched by action. Emissions continued to rise every year after the agreement was signed, leaving our “carbon budget” for staying within the 1.5C target shrinking ever smaller. On current trajectories, the world is expected to breach the 1.5C ceiling in less than a decade – and hit 3C of warming by the end of the century. Each passing year of inaction produces a compounding effect, necessitating ever steeper carbon reductions in future years.

Emission reduction trajectories associated with a 66% chance of limiting warming below 1.5C, without a reliance on net-negative emissions, by starting year. Solid black line shows historical emissions, while coloured lines show different pathways to limiting warming to 1.5C. | Carbon Brief

In short: time is rapidly running out. For this reason alone, 2021 was always going to be a critical year in the fight against climate breakdown. But then COVID-19 came along.

‘The Great Pause’

Twelve months ago it looked like 2020 was going to be another record breaking year for carbon emissions. But as COVID-19 rapidly spread around the world, businesses were forced to close, international travel ground to a halt, events were cancelled, and people were told to isolate at home.

Unsurprisingly, this ‘Great Pause’ caused carbon emissions to fall – according to the Global Carbon Project global emissions fell by 7% in 2020. Despite being the largest relative fall since the Second World War, this still pales in comparison to what is needed to meet the Paris targets. If warming is to be limited to 1.5C then emissions need to fall by 14% every year until 2040.

Some have cited these falling emissions as evidence that COVID-19 has helped to “save the planet”. As well being wildly exaggerated, these claims are also offensive: the idea that a pandemic that has caused immense suffering and killed more than a million people should be celebrated is obviously perverse. Pandemic-induced lockdowns do not provide a model for climate action.

More importantly however, those who say the pandemic will help the environment have got things precisely backwards. Like many other infectious diseases, COVID-19 has its origins in the encroachment of human activity into natural ecosystems. As more and more countries have sought to maximise economic growth, activities such as logging, mining, road building, intensive agriculture and urbanisation have led to widespread habitat destruction, bringing people into ever closer contact with animal species. As the United Nations’ environment chief, Inger Andersen, put it: “Never before have so many opportunities existed for pathogens to pass from wild and domestic animals to people.”

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, three-quarters of new or emerging diseases that infect humans originate in animals. In the case of COVID-19, it is believed that the virus originated in China’s bat population and was then transmitted into humans via another mammal host. On our current trajectory, while COVID-19 might be the first pandemic many of us have experienced, it will almost certainly not be the last.

COVID-19 is therefore not a random act of God. Like climate change, it is a symptom of accelerating environmental breakdown, which in turn is a product of an economic model that is reliant on growth and accumulation. Seen in this light, the idea that COVID-19 can somehow aid the environmental crisis is absurd: they are two sides of the same coin. To address both, we need to tackle the root cause.

Building back better?

As vaccines start to be rolled out across the world, attention is now turning to how the global economy can be rebooted. With unemployment soaring and economic hardship mounting, leaders will face growing pressure to reinstate ‘business as usual’ as quickly as possible. But doing this would not be a neutral act – it would be an active decision to deepen our environmental crisis. Restoring the status quo after defeating COVID-19 would be like celebrating beating lung cancer by smoking a hundred cigarettes. The cure for the disease can never be its cause.

The upshot is that the pandemic has shown that it is possible to radically restructure economies on short timescales, provided there is the political will to do so. Many countries have already promised to ‘build back better’ from the pandemic. In 2021, this rhetoric must be matched by reality. If the pandemic itself cannot cure the environmental crisis, the way we structure the recovery from it most certainly can.

Instead of spending billions to return national economies to their destructive path, governments must instead forge a different path by unleashing a vast programme of investment to decarbonise the global economy as fast as is feasibly possible, and bring our environmental footprint within fair and sustainable limits. Countries in the Global North that have played a disproportionate role contributing to environmental breakdown have a moral obligation to lead by example, while supporting a global just transition. As well as placing the global economy on a more sustainable path, this would create a new wave of high-skilled, low carbon jobs. Crucially, it would make future outbreaks of animal-borne diseases such as COVID-19 far less likely.

Some will question if we can afford such an undertaking. But the pandemic has shown that affordability is always a political constraint – not a technical one. Central banks have created trillions of dollars to prop up economies throughout the crisis – redirecting even a fraction of this towards green investments could put the world on track to meet the 1.5C temperature goal. With interest rates at record lows, there has never been a better time to turbocharge the green transition. The question is not whether we can afford to do this – it is whether we can afford not to.

In 2008 we bailed out the banks. This time, we must bail out the planet.

Crunch time for the carbon superpowers

Learning the right lessons from COVID-19 will be critical, but it’s far from the only important event this year. When it comes to meeting our climate goals, nowhere are the stakes higher than in the world’s largest two economies: the US and China. Together these two countries account for nearly half of all global emissions, and it will be virtually impossible to avert climate catastrophe without both making radical changes. Whether we like it or not, much of the power to materially reduce humanity’s carbon footprint lies in Washington and Beijing. Fortunately, 2021 is shaping up to be a decisive year in both countries.

Joe Biden has replaced Donald Trump as the 46th president of the United States. In the face of mounting pressure from climate campaigners, Biden announced that he will ensure the US reaches net-zero emissions no later than 2050. However, some fear that in power Biden will be heavy on rhetoric but light on concrete action. And with a political system awash with fossil fuel dollars and climate denial, there are questions about whether he can deliver, even if he tried to.

In China, President Xi Jinping has already pledged to make the country “carbon neutral” by 2060. Crucially however, the details of how this will be delivered will be unveiled in Communist Party’s long-awaited 14th five-year plan, covering 2021-25, which will be published in March. Of particular importance will be the binding targets that are set on the proportion of non-fossil fuels in the primary energy mix and the trajectory of coal power capacity. Both will have a huge impact on China’s emissions-reduction efforts over the coming five years.

Taken together, it’s not much of a stretch to say that President Biden’s climate package and China’s next five-year plan could be the most consequential policy packages in human history.

Beyond Paris

At its core climate change is a collective action problem: the short-term interests of each individual country are in direct conflict with longer-term interests of the planet as a whole. It’s therefore essential that national action is led by international cooperation. Once again, 2021 provides us with a critical juncture.

In November world leaders will gather in Glasgow for COP26, the successor to the landmark Paris meeting of 2015. Under the terms of the Paris deal, countries pledged to reconvene every five years to improve their carbon-cutting ambitions. COP26 will provide perhaps the last opportunity for world leaders to agree on targets that are compatible with limiting warming to 1.5C. By the time the next major COP meeting comes around in 2026, it may well be too late.

The amount at stake this year is therefore difficult to overstate. If there was ever to be a crunch point in the climate crisis, then 2021 is it. We face a fork in the road, and the decisions taken over the next 12 months will determine which path we choose. If promises to ‘build back better’ from COVID-19 are fulfilled; the Biden administration lives up to its pledges on climate change; China’s five-year plan delivers on its decarbonisation commitments; and COP26 is a success – then we might have a chance of averting climate catastrophe.

The flipside of this is that if none of this happens, our prospects look drastically different. If ‘build back better’ turns out to be an empty slogan; President Biden’s climate plan fails to pass the gridlock of the US political system; China’s five-year plan includes a vast expansion of coal power plants; and COP26 is a diplomatic failure – then we will find ourselves locked into a very dangerous trajectory indeed.

A constellation of events like this doesn’t come along every year. Time is short – so let’s make it count.

Teaser photo credit: By Mark Stewart – https://2009-2017.state.gov/img/12/48393/DSC_600_1.jpg, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=26064293