I was stigmatized as a queer female in rural Kentucky. My personal quest for equal rights now informs my push for a revamped public health approach to homelessness.

“I never met a Kentuckian who wasn’t either thinking about going home or actually going home.”- Kentucky Senator A.B “Happy” Chandler.

There is nothing quite like the beauty and comfort I find in my home state of Kentucky: from the state’s signature bluegrass and stunning Red River Gorge canyons to the “Bourbon Capital of the World” sign that signals I am nearly home when back for a visit.

These places represent my roots and growth, where I evolved into my authentic self.

I grew up on a farm among the rolling hills and world-renowned bourbon distilleries of the Kentucky Knob Region and couldn’t wait to move to the city (Lexington, Kentucky) after graduating high school. I spent eight pivotal years among the horse farms and bluegrass of Lexington, completing both my undergraduate and master’s degrees.

As I reflect on this pivotal period of my life, the steep terrain and unbridled horses remind me of the obstacles I overcame as a first generation female academic and the passion that fuels me (almost) every day. As I discovered more about my identity in those years, the intricate canyon system of Red River Gorge with its enormous rocks, sandstone cliffs, and waterfalls have come to exemplify my journey to uncovering and accepting my queerness. Each step and breath taken amongst the leaves and water representing new, exciting spaces that I am continually exploring and understanding within myself.

Copperas Falls in Red River Gorge near Campton, Kentucky (Credit: April Ballard)

I would be lying if I said that I have always felt this way about Kentucky. My love is the kind that has evolved overtime, requiring me to move away and realize that the relationship status “it’s complicated” can apply to more than just a romantic partnership.

Unfortunately, as a queer female, this state and its people have not always been kind to me. I grew up in an environment that made me ashamed of who I was, an environment that refused to recognize me or my basic human rights.

From an early age, I was told being gay was wrong. I never saw same-sex couples. And queerness was spoken about in whispers with discomfort; people at barbecues gossiping about this person’s cousin’s best friend, or that neighbor who keeps to themselves.

I have struggled to feel dignified because of queer guilt and shame, because so many of my loved ones have and continue to erase my identity. They distill me down to just being “liberal.” They have never asked about my sexual identity, but love to ask where my friend is during family gatherings. They leave me with feelings of guilt for being the “problem” child.

Being in such an environment made me hide parts of myself. I tucked pieces of myself away, hiding them so well that even I forgot they are there. Then I spent my adulthood in search of dignity. I had to uncover my true self, to decipher between the parts I created to make the world happy and those that are truly me. Queer readers out there know exactly what I am talking about.

This essay is also available in Spanish

My personal quest for dignity and equal rights connects me to those who often experience stigma and are stripped of their dignity. It shapes and drives my work as an environmental health scientist as I seek to address the environmental and social conditions that impact an individual’s ability to access water, sanitation, and hygiene while experiencing homelessness. Because of my struggles and experiences, I now actively and intentionally ground my work in dignity and human rights. Just as I have been afforded the opportunity to feel prideful in my queerness, people experiencing homelessness deserve to feel respected, valued, and seen regardless of their housing status.

Homeless camp in downtown Los Angeles. (Credit: Russ Allison Loar/flickr)

Homelessness is an ongoing national crisis, affecting 2.3 to 3.5 million people in the United States (U.S.) each year. Economic conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic may leave hundreds of thousands more homeless: 85 million households struggled to pay for their usual household expenses in the past week and 14.3 million adults living in rental housing are not caught up on rent, according to data collected in December.

When discussing the struggles and needs of people experiencing homelessness (more on the importance of people-centered language can be found here), we often drift toward “the basics:” food, water, warmth, and clothing. And while it is true that these are essential to survival, this approach defines our needs as humans too narrowly and fails to include dignity. We fail to ask:

Where can people experiencing homelessness get drinking water?

What else do they need water for (personal hygiene, handwashing), and where can they get this water?

Is clothing alone enough, or do people need to bathe regularly and have clean clothing to meet their basic needs?

Where does sanitation (or bathrooms) come into this? Where do people experiencing homelessness urinate and defecate? Why do they use these places?

And what are the physical, mental, and emotional impacts of all of this?

Dignity for people experiencing homelessness in relation to water, sanitation, and hygiene is rarely discussed in the U.S. This is because national estimates indicate that U.S. citizens have near universal (>99 percent) access to basic water and sanitation, and because we rely on bathrooms and laundry facilities mostly inside our homes: a one-stop shop.

Like many of you reading this, I wake up every morning and walk across the hall to brush my teeth in my bathroom. I drink water from the faucet in my kitchen. I urinate and defecate using my indoor, private flush toilet and wash my hands in my bathroom. And I shower at night in that same bathroom before I go to bed. All of these movements are done without thinking, other than being burdened with expensive period products (the “tampon tax”) and procuring toilet paper (#thankscovid19).

This is not the reality for people experiencing homelessness.

Instead, those living in encampments in Fresno, California, walk a mile and a half to access the nearest drinking water fountains. They are forced to urinate and defecate in public because there are no public restrooms nearby and they are denied access to facilities in local businesses.

Women living in shelters and on the streets of New York City deal with an insufficient number of clean, functioning, safe, and private toilets and an inadequate stock of items such as toilet paper and period products. They also report a loss of dignity because they have to wash their bodies in bathrooms at places like McDonald’s. They experience stigma and feelings of shame because of the possibility of period blood leakage and odor resulting from inability to change and bathe as needed.

And these struggles extend beyond city limits, impacting the rising number of rural people experiencing homelessness though limited research has focused on homelessness in rural communities.

Whether in large metropolitan areas or the mountains of rural Appalachia, too often we fail to consider the circumstances that people experiencing homelessness deal with every day and how our research, programs, and policies may contribute to such circumstances. We assume that if we build facilities, they will come but, the result is ineffective approaches that contribute to diminished self-worth and self-esteem among people experiencing homelessness.

But there is a path forward. By using harm reduction approaches, grounded in justice and human rights, and centering those experiencing homelessness in our decision-making and policies, we can create humanistic and equitable approaches to address the water, sanitation, hygiene needs of people experiencing homelessness and related emotional, mental, and physical health outcomes that result from unmet needs. My early work in Appalachia helped me re-imagine what good public health work can look like.

Reflections from Appalachia

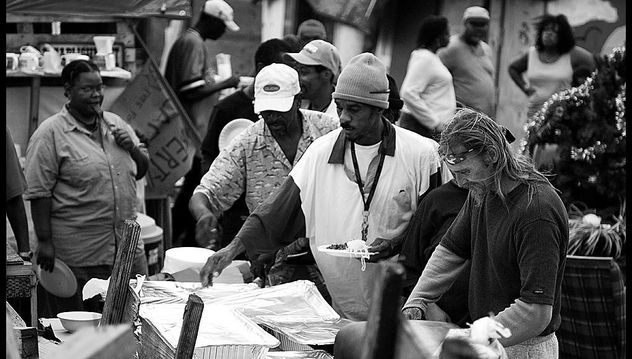

Author April Ballard refilling water at a Love Beyond Walls handwashing station for people experiencing homelessness residing in an encampment in Atlanta, Georgia (Credit: Alison Hoover)

My journey in water, sanitation, and hygiene among those without stable housing began amid the mountains and hollows of Central Appalachia where the opioid epidemic has hit hard and there are scant social, economic, and healthcare resources.

After graduating from my master’s program, I began working as a research assistant in Appalachian Kentucky. While working on projects focused on substance use, I spoke with many people experiencing homelessness and later conducted a study to understand their experiences with water, sanitation, and hygiene; the first of its kind in rural America.

I was also charged with co-hosting community cookouts to engage with and recruit participants. People would stop by for free food and stay for quick banter.

It took some time for people to open up and overcome their skepticism. After all, I was handing out free food in random parking lots. But over time my relationships with people grew as did the depth of our conversations.

Eventually, I heard many stories from people experiencing homelessness and people who use drugs. I listened as people described their deep-seated need for worthiness and respect; I noticed their need for eye contact, for remembering their name, for just being treated like a human.

One woman’s words in particular stuck with me. She explained the impact that other people’s harmful words had on her, saying that once you hear something enough, you start believing it. “They look at you like you’re crazy or you wouldn’t be in the situation you are, but you don’t have to be crazy to be poor.”

It was through these stories and navigation of my own identity that I realized the importance of dignity. I realized the importance of listening to the people that I wanted to help.

Now, as an environmental health scientist and practitioner, I seek to develop public health strategies that reduce the harms associated with homelessness such as providing soap for handwashing to prevent the spread of coronavirus, or providing a sufficient number of period supplies to menstruators to care for their health and hygiene and prevent reproductive tract infections and period stigma. I strive to place dignity at the center of what I do by asking people questions like “what do you want?” and “how do you want it?”

Reimagining public health approaches to homelessness

The Umoja Village Shantytown in Miami, Florida. (Credit: Danny Hammontree/flickr)

I have integrated these principles into my own work now in Atlanta, Georgia, a city with the highest income inequality in all of the U.S. and a growing homeless population.

During the pandemic, I have been handing out hygiene supplies, period products, and contraceptives to people experiencing homelessness with my colleagues, what we call “Dignity Packs.” Products provided allow people to meet their needs, prevent the transmission of coronavirus, and promote sexual and reproductive health. Our research team collects feedback via interviews, and we adjust contents and our approach week-to-week based on guidance from people experiencing homelessness. This approach allows those experiencing homelessness to dictate what products are available to them and how they receive it.

Direct feedback allowed us to veer away from traditional hygiene kits that are standardized and pre-packed. Instead, we set up a table where local organizations are providing food. We let people select the items they want (humanism) to meet their acute needs (pragmatism), like grabbing a few bars of soap to wash their hands and body. We let anyone (human rights) take any item with no requirements, no questions asked (autonomy).

We are proud of our efforts, but across the U.S. there is still so much work to do. Shelters and privately owned businesses overwhelmingly struggle to support the water, sanitation, and hygiene needs of those experiencing homelessness; both failing to meet critical human needs due to conditions that inadvertently perpetuate stigma.

Shelters are necessary and often well-meaning, however, limited capacity and scant resources allocated to them lead to conditions such as broken and dirty toilets, inadequate stocking of bathroom necessities, and lack of privacy that make those trying to access services feel demeaned and devalued. Requirements to access resources and facilities, such as “a desire to stay clean” and to “actively be working to end homelessness,” publicize and perpetuate stereotypes. And businesses screening those who ask to use the bathroom and denying access to those deemed unacceptable contribute to the extreme marginalization that those without homes experience.

As public health professionals and researchers, it is our job to both do and demand better.

We need to demand government support and funding to secure water, sanitation, and hygiene access for people experiencing homelessness. We need to broaden existing approaches to reduce the burden shelters and privately owned businesses face. And we need to reimagine our strategies; we need to focus on dignity.

This means using pragmatic approaches – seeking to reduce harm (infectious disease) as people continue to experience homelessness, recognizing that the elimination of homelessness may not be attainable or desirable.

This means employing humanism – leveraging approaches that value the respect, worth, and dignity of people experiencing homelessness. People should be met where they are and stigmatizing language and policies should not be used.

This means allowing for autonomy – respecting the decisions made by people, even if those decisions may cause harm to themselves. Preconditions should not be required to receive services and behaviors should not be prevented (drug use) as they may take away the person’s autonomy and cause distress.

This means protecting human rights – providing equitable, non-judgmental, and evidence-based services with no conditions. No person should be excluded because of their homeless status, drug use, sexual orientation, or race.

My quest for dignity that began within the borders of the Bluegrass state – the rolling hills of the Bluegrass Region, the cliffs in Red River Gorge, and the Appalachian Mountains – have helped to shape me as a public health professional and reimagine what dignity-centered public health work looks like. By leveraging harm reduction principles (pragmatism, humanism, autonomy, and human rights) and placing people experiencing homelessness at the helm of decision-making, we can create equitable and effective public health interventions that empower the people we are trying to help.

This essay is part of “Agents of Change,” an ongoing series featuring the stories, analyses and perspectives of next generation environmental health leaders who come from historically under-represented backgrounds in science and academia. Essays in the series reflect the views of the authors and not that of EHN.org or The George Washington University.

Banner photo: Author April Ballard handing out ‘Dignity Packs’ for people experiencing homelessness in Atlanta, Georgia (Credit: Alison Hoover