Ed. note: You can find Parts 1, 3, 4 and 5 on Resilience.org.

Tucked right at the end of the consultation document produced in the name of the Growth Board and One Nottingham is Appendix B. I suppose this section has been relegated to “Appendix B” because it does not fit the upbeat “always look on the bright side” optimism of the rest of the document. An analogy would be an embarrassment like a shameful family secret that no one wants to acknowledge to non-family members. Appendix B is where the authors of the report (almost) try to be realistic about what the situation in Nottingham really is….

To me what is really shameful is that the entire document did not BEGIN with some kind of acknowledgement, like this, of how bad things are….I quote:

The overall economic impact will be severe and unprecedented in peacetime.

The Coronavirus pandemic and the public health measures adopted in response is impacting the national, regional and local economy in three important ways: disruption to the supply of goods and services; demand shocks; and increased uncertainty. This looks set to reduce growth and drive unemployment –in ways which will impact some parts of Nottingham’s population harder than others.

Growth in the local economy has not stalled, it’s gone into reverse

Nottingham’s economy is forecast to shrink over the course of 2020 by some 5.7%, having suffered a severe contraction in economic output in April to June. Based on assumptions of a v-shaped recovery, economic growth is expected to be 3.3% in 2021, slightly above the UK average.3 City sectors which are being most affected are tourism and hospitality; creative industries; leisure services; transport and manufacturing, as well as the wholesale and retail sector. The severity of impact is dependent on how successfully the economy emerges from lockdown and whether there is a major local outbreak post-lockdown. The number of high risk sectors is expected to fall from 12 in 2020 to 5 in 2021 with GVA associated with this group falling by 27.4%.

The lockdown will have a major impact on employment with some sectors especially hard hit…

End of Quote Text continues…

There is a word for this embarrassed relegation of reality to the back pages – if this were the action of an individual it would be pretty close to what a psychotherapist would called DENIAL An issue is pushed away, out of mind with no real attention paid to it. In this case the truth is stated nominally but at the end of the text and in an appendix so that it does not have to be addressed and spoil the “vision” for Nottingham.

Consistent with my conclusion that the “Growth Board” and “One Nottingham” are unable to deal with unpleasant realities is this sentence, which can be found right at the end of Appendix B and of the document.

“COVID-19 (especially when combined with Brexit, climate change and other strategic drivers) will present long-term economic challenges of a kind never witnessed in modern times. But –based on history –the economy will recover, the labour market will improve and prospects will brighten eventually. The need to focus on long-term gains in labour productivity remains fundamental to regaining prosperity and raising living standards in Nottingham, as elsewhere.”

Well, that’s all right then! Thank goodness. The story will have a happy ending – “based on history”. It’s always darkest just before the dawn and the great God “economic growth” will re-appear, rise in the sky and throw its warmth across the places where entrepreneurial efforts have sown exciting innovations, thus bringing forth “wealth creation” in abundance.

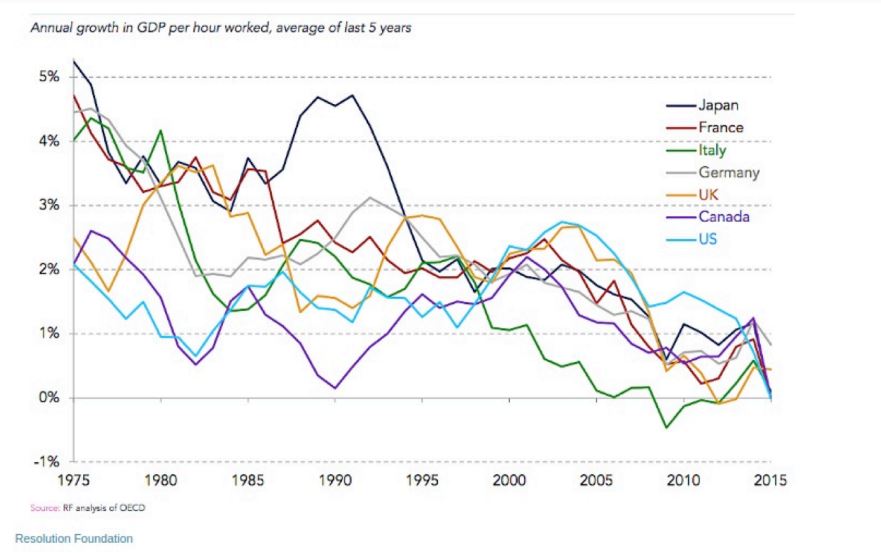

Or maybe not…. The “need to focus on long term gains in labour productivity” may be hampered in Nottingham as they are everywhere else in the OECD, as witness these graphs:

https://www.cusp.ac.uk/themes/aetw/wp12/ (CUSP is the centre for sustainable prosperity)

http://images.feasta.org/2017/04/201704-davey-slide1.png [update] (ed. note: Link seems to be broken)

What the graphs show is that labour productivity has been slowing across the OECD now for half a century –almost to zero. In other words, the Covid-19 crisis is serious but there were serious problems before the crisis too – and that the growth that the Growth Board intends to achieve locally, was already failing. Indeed economists have had a name for this problem – “secular stagnation”. But you would not know that reading the document, because the document lacks any kind of economic analysis – of international, national and local trends.

The Limits to Growth forecast for the first two decades in the 21 century

The current situation was predicted as early as 1972 with the publication of a study titled “The Limits to Economic Growth”. This book, authored by a number of scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, foresaw that growth would come to a halt in the first two decades of the 21st century, followed by a decline in production and a population crisis. Their reasoning was essentially that further expansion by industrial economies would eventually be halted by the negative impacts of pollution and wastes as well as by the depletion of essential materials and energy.

Fast forward to the present and we have a number of crises caused by pollution like the climate crisis and biodiversity collapse, while at the same time depletion of oil, gas and coal reserves has exhausted cheap to access sources of fossil fuels. There are also good reasons to believe that while there are sufficient affordable sources of minerals to start a renewable energy revolution – like lithium, zinc, nickel, cobalt and rare earths – these are however insufficient to get very far and complete such a revolution by bringing it to anything close to the scale of the current global fuel based transport fleet.

The economy is embodied and embedded in the material world and is also an energy system. For example climate change is having and will have real world physical impacts like droughts and flooding which brings down crop yields. At the same time the depletion of fossil fuels and the resort to renewables is actually leading to increasing energy and material input costs – in the 1960s the global energy cost of energy was less than 2%. By the end of the century it was 3.5% and now it is about 8%. This has real world effects.

A modern economy mostly consists of human guided machines, equipment, vehicles, appliances, structures and infrastructures – nearly all of which are powered and/or require energy to construct and maintain them.

The productive power of a modern economy is because of the energy that flows through this system. Work has a meaning in physics as well as in economics, and the work that an averagely fit person can do with their muscles is about 3kWh a day – but the energy flowing through the machines of the European economy is over 100 times this per capita and over 200 times this per capita in the USA. However some of the energy must be devoted to the extraction, refining, delivery and the conversions of the energy system itself. When this proportion goes up from less than 2% to 8% then the energy delivered to the rest of the economy falls from 98% to 92%…..and counting.

Effect on Personal Prosperity

In order to understand what is happening in Nottingham’s economy, and in the economies of cities like Nottingham, it is necessary to consider how this hits the prosperity of most people. In 2008 when the oil price went to over $140 for a barrel of oil this had a big impact as energy bills rose and the price of goods which take a lot of energy to produce also rose – like food. But this left people and companies with less money to be spent on other goods and services, and less money for people to use to service their debts. It was massively deflationary and led to a financial sector crisis.

As energy bills have risen people have less money for other things and have increasingly covered the gap by borrowing. Whatever their nominal income, the average person’s prosperity is shrinking and this has massive implications for their ability to go shopping – as well as their ability to patronise leisure, the arts and hospitality venues and to visit Nottingham for these purposes. They simply lack the purchasing power for discretionary purchases.

The John Collins Strategy was never sustainable – the decline in ‘discretionary expenditure’

The previous economic development strategy of turning Nottingham into the shopping capital of the East Midlands and making it a cultural and nightlife centre was only ever sustainable while the economy was booming, prosperous and the credit was flowing. Now that it isn’t, the John Collins strategy has reached its limits with the growth limits of the economy. (As I predicted would occur eventually back in 2004, although I was clumsy in my prediction for oil prices. In 2004 I did not fully recognise that rising oil prices would be braked because the rest of the economy cannot afford high prices. This means that the oil companies will be eventually driven towards bankruptcy as it becomes impossible to cover rising costs of extraction/refining and fuel transport by putting up the retail price of fossil fuels.

http://www.bgmi.us/web/bdavey/NottmDebtfuel.htm

As regards how ordinary people are impacted by these processes, Dr Tim Morgan explains in his blog “Surplus Energy Economics”:

There is a sequence of hierarchy in how the ‘average’ person spends his or her income. The first calls are taxation, and the cost of household essentials. Next come various liens on income owed to the financial and corporate system – these are the household counterparts of the streams of income on which so much corporate activity and capital asset value now depend. ‘Discretionary’ (non-essential) spending – everything from leisure and travel to the purchase of durable and non-durable consumer goods – is funded out of what remains, after these various prior calls have been met.

Putting these two facts together leads to some striking conclusions. Because discretionary consumption comes last in the pecking-order of spending – and because a large and growing slice of apparent ‘income’ is no more than a cosmetic product of financial manipulation – then it follows that the underlying and sustainable level of discretionary expenditures is far lower than is generally assumed.

In essence, discretionary sectors of the economy are now on life-support, kept in being only by the dripfeed of credit and monetary stimulus. Additionally, the ability of households to sustain the stream-of-income payments to the financial and corporate sectors is hanging by a thread.

This means, first, that, as and when credit and monetary adventurism reach their practical limits, whole sectors of the economy will contract very severely.

Second, it means that we have reasonable visibility on the processes by which asset prices will slump into a new equilibrium with much-reduced economic prosperity.

https://surplusenergyeconomics.wordpress.com/2020/11/23/185-the-objective-economy-part-two/

Implications for Retail, Culture and Leisure and FinTech

This analysis has enormous implications for a large part of the “recovery programme” offered to us by the “Growth Board” and “One Nottingham”.

It should be blindingly obvious that the consultation document offers us “an exciting vision” of a continued expansion of sectors that are really vulnerable to these developments. Re-opening the economy for Covid is not going to turn round the prospects for retail in the city centre for a start. The so called “Retail Apocalypse” will continue.

More than this though – right at the cutting edge of the “Growth Board” strategy we are offered a vision of Nottingham as a city of culture and the arts, yet however worthy the idea, there is the key ECONOMIC issue of whether ordinary people will be able to afford to pay for this culture, arts and leisure. These are clearly the sorts of expenditures that are paid for out of the discretionary part of people’s income and this is the very part where available purchasing power is drying up. If the idea is that such culture will attract people to Nottingham by being for free – but that the people who come here will then buy more in shops and local restaurants – the same issues that are producing the retail apocalypse will apply.

This is a problem that exists independently of Covid-19. The Covid-19 crisis has brought this issue forward but it did not create it and ending the Covid restrictions will not resolve it…..especially as the Brexit crisis is likely to make the shortage of purchasing power even worse. If, as one can expect, food prices and other essentials become more difficult to get hold of after December 31st then this will also reduce whatever income people have remaining for “discretionary expenditure”, not to mention making servicing debt more difficult.

As the demand for help from food banks increases can we really expect that spending on the arts and culture will be getting top priority in how people allocate their available money?

(To be continued )

Teaser photo credit: By Smashman – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3941370