Economic growth is closely linked to increases in production, consumption and resource use and has detrimental effects on the natural environment and human health. It is unlikely that a long-lasting, absolute decoupling of economic growth from environmental pressures and impacts can be achieved at the global scale; therefore, societies need to rethink what is meant by growth and progress and their meaning for global sustainability.

Key messages

- The ongoing ‘Great Acceleration’ [1] in loss of biodiversity, climate change, pollution and loss of natural capital is tightly coupled to economic activities and economic growth.

- Full decoupling of economic growth and resource consumption may not be possible.

- Doughnut economics, post-growth and degrowth are alternatives to mainstream conceptions of economic growth that offer valuable insights.

- The European Green Deal and other political initiatives for a sustainable future require not only technological change but also changes in consumption and social practices.

- Growth is culturally, politically and institutionally ingrained. Change requires us to address these barriers democratically. The various communities that live simply offer inspiration for social innovation.

This narrative is part of a series called ‘Narratives for change’ published by the EEA

Growth and narratives for change

The world is undergoing rapid change. Numerous drivers of change interact in a highly complex interplay of human needs, desires, activities and technologies (EEA, 2020) and contribute to the Great Acceleration in human consumption and environmental degradation. Human civilisation is currently profoundly unsustainable.

These dynamics have to change. Governments, scientists and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) worldwide are coming together to try to devise new ideas, policies, blueprints and narratives. This narrative is part of a series called ‘Narratives for change’ published by the EEA. It presents alternative perspectives on economic growth and human progress and explores the diversity of ideas needed to transform our society towards sustainability goals and fulfil the ambitions of the European Green Deal.

By building on the insights of EEA reports on drivers of change and sustainability transitions (EEA, 2017, 2019a, 2019b, 2020), this briefing explores alternative ideas about growth and progress with the aim of broadening the sustainability debate. This comes at a crucial time for the EU, which faces urgent challenges and opportunities associated with fundamental change. The EU has achieved unprecedented levels of prosperity and well-being in recent decades, and its social, health and environmental standards rank among the highest in the world (EEA, 2019c).

Maintaining this position does not have to depend on economic growth. Could the European Green Deal, for example, become a catalyst for EU citizens to create a society that consumes less and grows in other than material dimensions?

As global decoupling of economic growth and resource consumption is not happening, real creativity is called for: how can society develop and grow in quality (e.g. purpose, solidarity, empathy), rather than in quantity (e.g. material standards of living), in a more equitable way? What are we willing to renounce in order to meet our sustainability ambitions?

Global-scale, long-lasting and absolute decoupling may not be possible

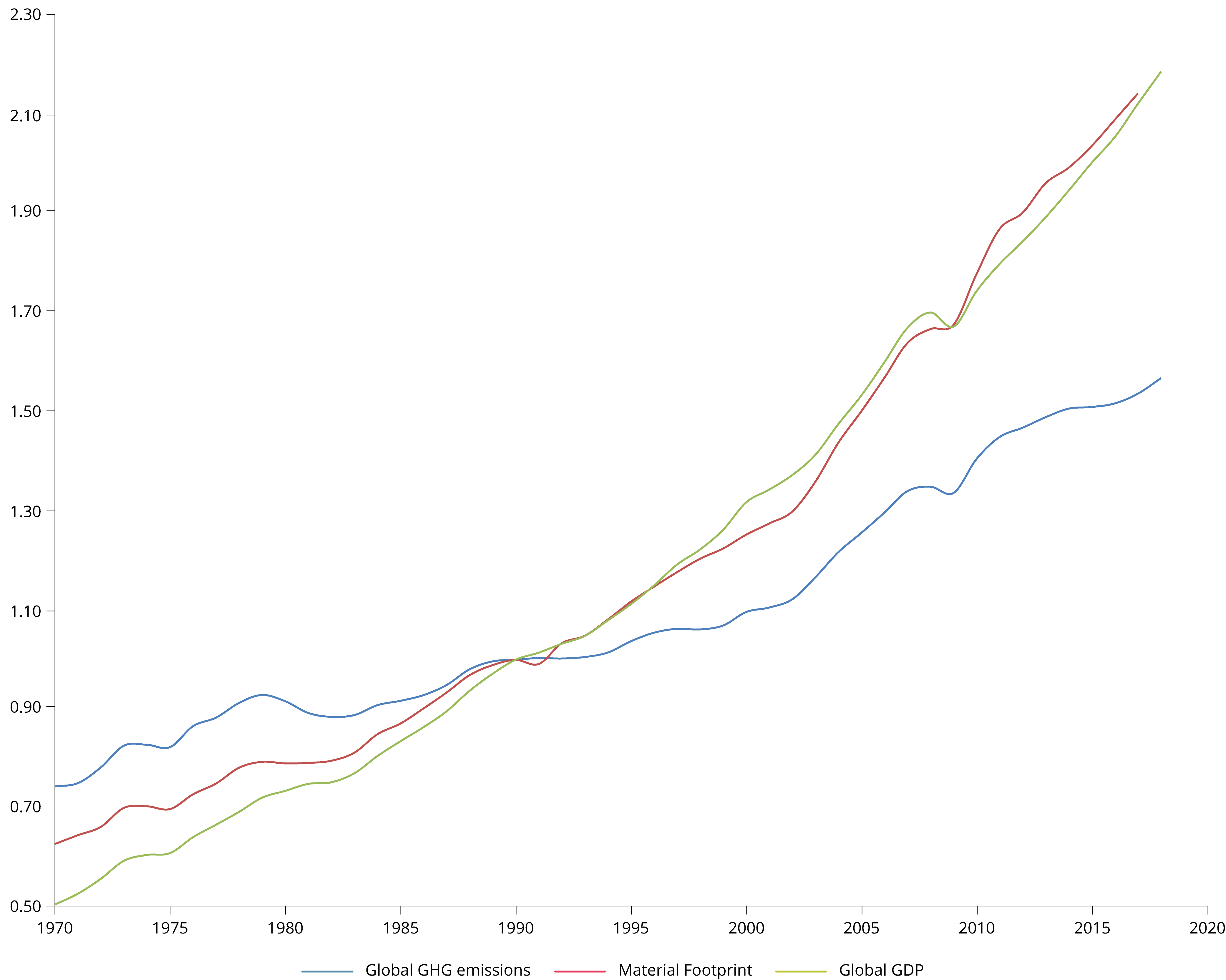

Globally, growth has not been decoupled from resource consumption and environmental pressures and is not likely to become so (Parrique et al., 2019; Hickel and Kallis, 2020; Wiedmann et al., 2020). The global material footprint, gross domestic product (GDP) and greenhouse gases emissions have increased rapidly over time, and strongly correlate (Figure 1). While population growth was the leading cause of increasing consumption from 1970 to 2000, the emergence of a global affluent middle class has been the stronger driver since the turn of the century (Panel, 2019; Wiedmann et al., 2020). Furthermore, technological development has so far been associated with increased consumption rather than the reverse.

Europe consumes more and contributes more to environmental degradation than other regions, and Europe’s prospects of reaching its environmental policy objectives for 2020, 2030 and 2050 are poor (EEA, 2019c). Several of Europe’s environmental footprints exceed the planetary boundaries (Sala et al., 2020; EEA/FOEN, 2020).

Figure 1. Relative change in main global economic and environmental indicators from 1970 to 2018

Sources: Modified from Wiedmann et al. (2020). Reproduced under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Data from Olivier and Peters (2020) for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions; UNEP and IRP (2018) for material footprint; and World Bank (2020a) for GDP.

More info

High-level policies (e.g. the European Green Deal and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, SDGs) propose decoupling of economic growth and resource use as a solution. However, scientific debates on the possibility of decoupling date back to the 19th century and there is still no consensus. Recent studies, such as Hickel and Kallis (2020) and Parrique et al. (2019), find no evidence of absolute decoupling between growth and environmental degradation having taken place on a global scale.

While some EU countries achieved a reduction in some forms of pollution between 1995 and the mid-2010s (e.g. acidification, eutrophication, greenhouse gas emissions), the decoupling between growth and environmental footprints (e.g. water, materials, energy and greenhouse gases) associated with EU consumption patterns is often relative and varies between countries (Sanyé-Mengual et al., 2019; NTNU, 2020).

Such changes are associated with a combination of factors (see EEA, 2020). These include structural economic change, which led to the outsourcing of significant shares of energy-intensive activities to non-EU countries and the financialisation of EU economies (Kovacic et al., 2018). An absolute reduction of environmental pressures and impacts would require fundamental transformations to a different type of economy and society — instead of incremental efficiency gains within established production and consumption systems.

100 % circularity is impossible

If economic growth cannot be decoupled from resource use, can the use of existing resources be extended within the economy? Circular economy policies aim to improve waste management and induce responsible production and consumption cultures. The circular economy, however, may not deliver the transformation to sustainability if circularity measures fuel a growth strategy that leads to increased material consumption. An economy downsized to match the material input that it can recycle would be a very slow economy (Kovacic et al., 2019a).

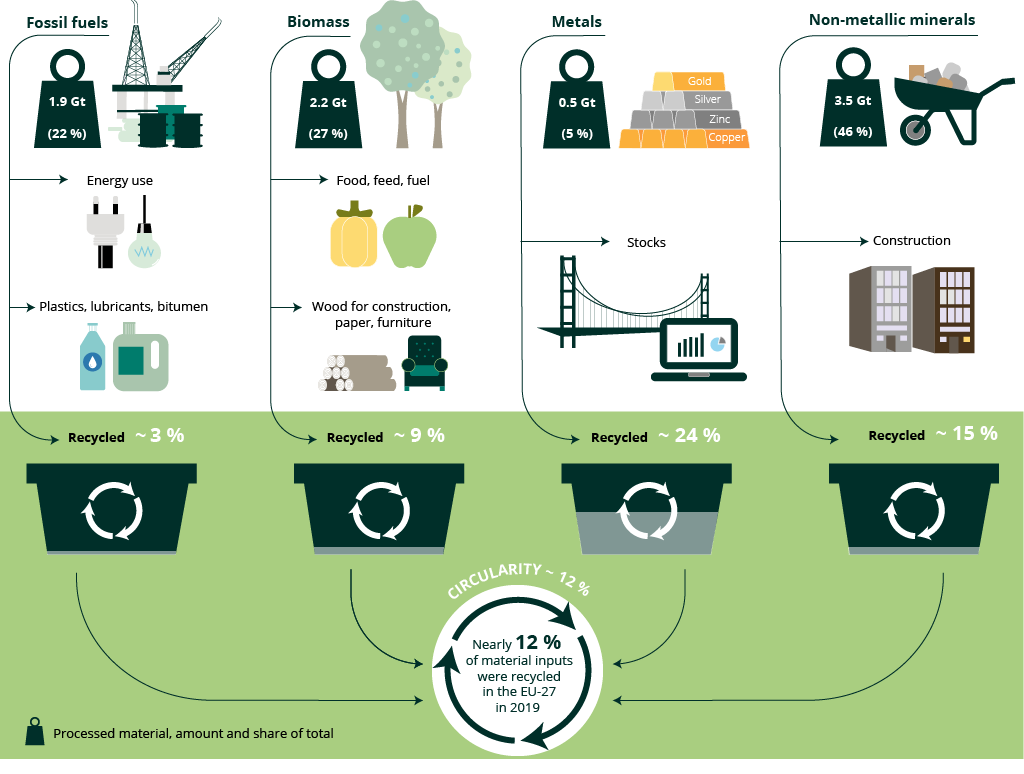

The concept of ‘circular economy’ suggests that material resources could be increasingly sourced from within the economy, reducing environmental impact by increasing the reuse and recycling of materials. However, this socio-technical ‘imaginary’ has a limited potential for sustainability, as revealed by biophysical analysis (Kovacic et al., 2019a). In fact, at the scale of the whole economy only around 12% of the material input was being recycled in the EU-27 in 2019 (Eurostat, 2020). Given current product design and waste management technologies, recycling rates of materials such as plastics, paper, glass and metals can — and should — be greatly increased in line with EU policy ambitions. However, overall, recyclable material remains a meagre portion of material throughput.

The low potential for circularity is because a very large share of primary material throughput is composed of (1) energy carriers, which are degraded through use as explained by the laws of thermodynamics and cannot be recycled, and (2) construction materials, which are added to the building stock, which is recycled over much longer periods (Figure 2). This can be interpreted in the light of Tainter’s (1988) study of the collapse of complex societies: as complexity increases, there are diminishing marginal returns on improvements in problem-solving; hence, improvements at the local scale have a very small impact on the overall system.

Moreover, high throughput and low rates of recycling appear to be conditions for high productivity (Hall and Klitgaard, 2012). Advanced societies require high throughputs of energy and materials to maintain their organisational complexity (Tainter and Patzek, 2012). What these insights point to is the need to rethink and reframe societal notions of progress in broader terms than consumption.

Figure 2. Schematic representation of limits of circularity in the EU-27, 2019

Note: The figures in brackets (top) indicate the share of a given category of material of total processed material and refer to year 2014. The figures for recycling (bottom) indicate the share of recycling in each category and refer to year 2019. The category ‘Metals’ also includes associated extractive wastes.

Source: Data from Mayer et al. (2019) for processed material and Eurostat (2020) for recycling rates.

Avenues for rethinking growth and progress

Historically, modern states embraced economic thought that focused on economic growth and conceptualised social and environmental problems as externalities. As a result, growth is culturally, politically and institutionally ingrained. Worldwide, the legitimacy of governments cannot be separated from their ability to deliver economic growth and provide employment.

However, recent decades have seen a variety of initiatives to ‘rethink economics’ (including the movement with that name, Rethinking Economics, 2020) and develop theoretical perspectives that combine attention to the legitimate needs of the present human population with the need for a transformation to a sustainable future. Ecomodernist thought [2] promotes ‘green growth’ through scientific and technological progress.

Other scholarly fields and social movements went beyond the idea of green growth (Wiedmann et al., 2020) and proposed concepts like “doughnut economics” (Raworth, 2017) and “degrowth” (Demaria et al., 2013), which are outlined in Table 1.

Similarly, radical perspectives are offered by fields such as transition studies, post-normal science, ecological economics and resilience studies. The EEA (2017) summarised this literature and noted:

The challenge in coming years will be to bring these insights into mainstream policy processes and consider how they can be operationalised effectively in support of Europe’s sustainability objectives.

Social, political and technological innovation is called for to translate alternative ideas about growth into new ways of living. Inspiration is also to be found in very old traditions. Ernst Schumacher’s (1973) slogan ‘Small is beautiful!’ had deep roots in oriental as well as occidental thought.

There is a range of religious, spiritual and secular communities that are less materialistic, consume less and seek lifestyles simpler than that of mainstream society. The so-called ‘plain people’ (e.g. the Amish and the Quakers) practise simple living as part of their religious identity. In ecovillages, the simpler lifestyle is connected to environmentalism (GEN Europe, 2020). Countless internet communities are devoted to simple living to increase quality of life, reduce personal stress and reduce environmental pressures. Among the schools of thought on growth, the degrowth movements are particularly interested in simple living.

Europe’s fundamental values are not materialistic

In liberal societies, a multiplicity of values is cherished. The European heritage is much richer than material consumption. The fundamental values of the EU are human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality and the rule of law, and they cannot be reduced to or substituted by an increase in GDP. If there are limits to economic growth and to the current trajectory (i.e. ‘plan A’), plan B to achieve sustainability is to innovate lifestyles, communities and societies that consume less and yet are attractive to everybody and not only individuals with an environmental, spiritual or ideological interest.

Plan B is extremely challenging. Economic growth is highly correlated with health and well being indicators, such as life expectancy and education. Thanks to economic growth, the portion of the world’s population living in extreme poverty, as defined by the poverty line of USD 1.90 a day, fell from 36% in 1990 to 10% in 2015 (World Bank, 2020b). In terms of doughnut economics, it is possible that the doughnut between basic human needs and planetary boundaries is very thin (O’Neill et al., 2018). However, economic growth has not contributed to decreasing inequality, either between or within countries (Piketty, 2013).

Although Europe remains home to the most equal societies globally (EC, 2017), inequalities have nonetheless been rising too, albeit at a slower rate than in other regions. Moreover, there is a risk that younger people in Europe today could be less well off than their parents, as a result of high unemployment levels among young people (EC, 2017). It may be that plan B also has to be considered in order to leave nobody behind, particularly the most vulnerable in the population.

Old and new narratives about the need for a universal basic income, an idea that is supported by nearly two thirds of Europeans (Lam, 2016) and calls for reduced working hours, are nowadays brought more prominently to the fore. These measures are suggested as possible ways to resolve gender biases and the unequal distribution of working time across society (De Spiegelaere and Piasna, 2017), as well as limiting the impacts of the growth in precarious and insecure work in Europe.

While the planet is finite in its biophysical sense, infinite growth in human existential values, such as beauty, love, and kindness, as well as in ethics, may be possible. Society is currently experiencing limits to growth because it is locked into defining growth in terms of economic activities and material consumption. The imperative of economic growth is culturally, politically and institutionally ingrained. As emphasised by Commission Vice-President Frans Timmermans (EC, 2019), however, the need for transformative change, amplified and accentuated by the COVID-19 pandemic, calls for a profound rethinking of our activities in the light of sustainability.

What could be achieved in terms of human progress if the European Green Deal is implemented with the specific purpose of inspiring European citizens, communities and enterprises to create innovative social practices that have little or no environmental impacts yet still aim for societal and personal growth?

Footnotes

[1] The period after the 1950s marks a unique period in human history of unprecedented and accelerating human-induced global socio-economic and environmental change, which has become known as ‘the Great Acceleration’ (Steffen et al., 2015).

[2] See, for example, the ecomodernist manifesto

Acknowledgements

Authors:

Strand, R., Kovacic, Z., Funtowicz, S. (European Centre for Governance in Complexity)

Benini, L., Jesus, A. (EEA)

Inputs, feedbacks, and review:

Anita Pirc‑Velkavrh (EEA), Jock Martin (EEA), Zuzana Vercinska (EEA), Kees Schotten (PBL), Igor Struyf (MIRA), Wolf-Ott Florian (Umweltbundesamt Austria), Eionet NFPs and NRC-FLIS, and the EU Environmental Knowledge Community

References

De Spiegelaere, S. and Piasna, A., 2017,The why and how of working time reduction, European Trade Union Institute.

Demaria, F., et al., 2013, ‘What is Degrowth? From an Activist Slogan to a Social Movement’,Environmental Values22, pp. 191–215 (DOI: 10.2307/23460978).

EC, 2017, White Paper on the future of Europe and the way forward — reflections and scenarios for the EU27 by 2025, European Commission, Brussels, accessed 18 January 2019.

EC, 2019, Frans Timmermans, European Commission., accessed 3 September 2020.

EEA, 2017, Perspectives on transitions to sustainability, EEA Report No 25/2017, European Environment Agency, accessed 8 June 2019.

EEA, 2019a, Sustainability transitions: policy and practice, EEA Report No 9/2019, European Environment Agency, accessed 7 February 2020.

EEA, 2019b, Sustainable transitions in Europe in the age of demographic and technological change, European Environment Agency.

EEA, 2019c, The European environment — state and outlook 2020: knowledge for transition to a sustainable Europe, accessed 6 June 2020.

EEA, 2020, Drivers of change of relevance for Europe’s environment and sustainability, No 25, European Environment Agency.

EEA/FOEN, 2020, Is Europe living within the limits of our planet? An assessment of Europe’s environmental footprints in relation to planetary boundaries, Publication No 1, EEA/FOEN, accessed 3 September 2020.

Eurostat, 2020, ‘Material flows in the circular economy – circularity rate’, Eurostat Statistic Explained, accessed 9 November 2020.

GEN Europe, 2020, ‘European Ecovillages’, Global Ecovillage Network – Europe, accessed 3 September 2020.

Haas, W., et al., 2015, ‘How Circular is the Global Economy?: An Assessment of Material Flows, Waste Production, and Recycling in the European Union and the World in 2005’, Journal of Industrial Ecology19(5), pp. 765-777 (DOI: 10.1111/jiec.12244).

Hall, C. A. S. and Klitgaard, K. A., 2012, Energy and the Wealth of Nations. Understanding the Biophysical Economy, Springer New York, New York, NY.

Hickel, J. and Kallis, G., 2020, ‘Is Green Growth Possible?’, New Political Economy25(4), pp. 469–486 (DOI: 10.1080/13563467.2019.1598964).

Kovacic, Z., et al., 2018, ‘Finance, energy and the decoupling: an empirical study’,Journal of Evolutionary Economics28(3), pp. 565-590 (DOI: 10.1007/s00191-017-0514-8).

Kovacic, Z., et al., 2019a,The Circular Economy in Europe: Critical Perspectives on Policies and Imaginaries, Routledge.

Kovacic, Z., et al., 2019b,The Circular Economy in Europe: Critical Perspectives on Policies and Imaginaries, Routledge.

Lam, A., 2016, ‘Two-thirds of Europeans for basic income – Dalia CEO presents surprising results in Zurich’, Dalia Research, accessed 15 August 2018.

Mayer, A., et al., 2019, ‘Measuring progress towards a circular economy: A monitoring framework for economy‐wide material loop closing in the EU28’, Journal of Industrial Ecology23(1), pp. 62-76.

NTNU, 2020, ‘Environmental footprints Data Explorer’, accessed 19 October 2020.

OECD, 2011, Fostering Innovation for Green Growth, OECD, accessed 26 November 2020.

Olivier, J. G. J. and Peters, J. A. H. W., 2020, Trends in Global CO2 and Total Greenhouse Gas emissions: 2019 report, No Report no. 4068, PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, The Hague, accessed 20 February 2020.

O’Neill, D. W., et al., 2018, ‘A good life for all within planetary boundaries’, Nat Sustain1(2), pp. 88–95 (DOI: 10.1038/s41893-018-0021-4).

Panel, I. R., 2019, Global Resources Outlook 2019: Natural Resources for the Future We Want, No ISBN: 978-92-807-3741-7, United Nations Environment Programme, accessed 3 September 2020.

Parrique, T., et al., 2019, Decoupling Debunked: Evidence and arguments against green growth as a sole strategy for sustainability, European Environment Bureau, accessed 3 September 2020.

Piketty, T., 2013, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Belknap Press: An Imprint of Harvard University Press.

Raworth, K., 2017, Doughnut economics: seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist, Chelsea Green Publishing.

Rethinking Economics, 2020, ‘Why Rethink Economics?’, Rethinking Economics, accessed 3 September 2020.

Sala, S., et al., 2020, ‘Environmental sustainability of European production and consumption assessed against planetary boundaries’, Journal of Environmental Management269, p. 110686 (DOI: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110686).

Sanyé-Mengual, E., et al., 2019, ‘Assessing the decoupling of economic growth from environmental impacts in the European Union: A consumption-based approach’, Journal of Cleaner Production236, p. 117535 (DOI: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.07.010).

Schumacher, E. F., 1973,Small is beautiful: a study of economics as if people mattered, Blond & Briggs, London.

Steffen, W., et al., 2015, ‘The trajectory of the Anthropocene: the great acceleration’, The Anthropocene Review2(1), pp. 81-98 (DOI: 10.1177/2053019614564785).

Tainter, J., 1988,The Collapse of Complex Societies, Cambridge University Press.

Tainter, J. A. and Patzek, T. W., 2012,Drilling Down: The Gulf Oil Debacle and Our Energy Dilemma, Copernicus.

UNEP and IRP, 2018, ‘Global Material Flows Database’, accessed 9 January 2020.

Wiedmann, T., et al., 2020, ‘Scientists’ warning on affluence’, Nature Communications11(1), p. 3107 (DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-16941-y).

World Bank, 2020a, ‘GDP (constant 2010 US$)’, The World Bank Data, accessed 19 November 2020.

World Bank, 2020b, Poverty – Overview, World Bank., accessed 3 September 2020.

Identifiers

Briefing no. 28/2020

Title: Growth without economic growth

HTML – TH-AM-20-028-EN-Q – ISBN 978-92-9480-321-4 – ISSN 2467-3196 – doi: 10.2800/781165

PDF – TH-AM-20-028-EN-N – ISBN 978-92-9480-320-7 – ISSN 2467-3196 – doi: 10.2800/492717

This piece is shared under the following Creative Commons CC by 2.5 DK license.

Teaser Photo: © Ricardo Gomez Angel on Unsplash