Ed. note: This article first appeared on ARC2020.eu. ARC2020 is a platform for agri-food and rural actors working towards better food, farming, and rural policies for Europe.

Since he first set foot in Vachères-en-Quint in La Drôme, France, almost half a century ago, Sjoerd Wartena (left) has followed in the footsteps of the older generation, who taught him how to farm and raise animals in these austere uplands. Still fascinated by the ways of our predecessors, he has taken to tracing the remnants of farming practices indigenous to the area. Here he reflects on what we can learn from past generations and their ability to adapt to harsh conditions.

Since he first set foot in Vachères-en-Quint in La Drôme, France, almost half a century ago, Sjoerd Wartena (left) has followed in the footsteps of the older generation, who taught him how to farm and raise animals in these austere uplands. Still fascinated by the ways of our predecessors, he has taken to tracing the remnants of farming practices indigenous to the area. Here he reflects on what we can learn from past generations and their ability to adapt to harsh conditions.

In these 500 hectares of mainly wild nature, I now constantly look for signs of the ancestors of the indigenous population. I have always been fascinated by the life of the previous generation that was born and bred here, who shaped our way of practicing agriculture and animal husbandry.

There is still one old peasant alive, Mr. Robert Parat (94 years old) who has experienced all this and can recount it with a razor-sharp memory. He partly showed me the way, for example to a series of six terraces, which were completely overgrown, and of which I had been made aware several years ago by a cadastral indication that this concerned workable land.

I found some walls and started to discover and clear access paths. Jochen and Oda (our successors on the goat farm) started to help, mainly by sawing juniper and pine trees and throwing them down, where the green was pulverized by a chopper and then distilled in the herb cooperative I founded, while the wood in another machine was shredded, dried and then fuelled our central wood heating.

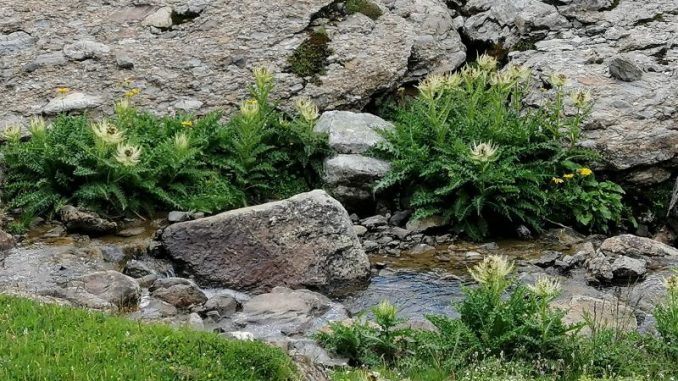

Water was a rare commodity: every measly trickle from the mountains was received with the utmost care. Photo © Valérie Géslin

Every measly trickle

Robert Parat explained to me why those terraces were built, and I discovered it for myself. At the top was a small spring, which had been drained by the last farmers of Vachères in a well constructed in the fifties and which had been transported by channels to the terraces below.

Water was a rare commodity in this god-forsaken village, where 100 people nevertheless lived in 1850, and every measly trickle here and there from the mountains was received with the utmost care.

Only in autumn and winter was there sometimes enough to run two millstones in the lowest part of the village, do the laundry for six months and let the cattle drink close to the stable. For the rest of the year, the children roamed with a cow and some goats all over the ravines and secluded valleys to find patches of grass and, above all, a little water here and there.

In the summer, water use was strictly regulated, and although the main source of water was drawn from a pipe leading to the village, there was only water for one or two hours a day for the most necessary needs. The deep trench in front of that pipe was cut into the stony soil by a group of Italian road workers in the early 20th century. According to the Escarron brothers, God have mercy on their souls – who were the first to show us the way in Vachères – the poor people mainly ate onions.

Cairns were built to mark soil that was stone free and worked. Image: A cairn on Plateau d’Emparis in the French Alps. Photo by Dominicus Johannes Bergsma, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

There’s hemp in them there hills

In the meantime I have restored the roads to the terraces. I can even get there by tractor. But to start growing vegetables, chickpeas and potatoes again, or to plant lavender and thyme, I lack the energy, however much I like to preserve the link to previous generations.

I also made passable a fairly steep road to the top of the hill. In the past, this road was necessary to get wood from above, which was then transported down on a sledge. Now the hunters use it and the road is included in my archeological circuit.

That circuit also includes two elongated terraces with fairly high walls, 4 meters high here and there, without water and probably intended for vines. Now, with my grandchildren, I put a stone booth on it, likely to be used for shelter and tool storage.

The circuit also includes an accidentally discovered water basin of approximately 8 square meters. Here again a moderately trickling source that fills the basin and where the hemp used to be rotted to make fibers for rope and clothing. That basin is also on a steep slope due to the water presence.

The vegetable gardens were spread over the entire area in places where some water came from the rocks. A few terraces have also been constructed around this basin and there is even a rusted jug hanging from a branch with which the lettuce could be watered.

The path to this basin was not found at first, but if you suddenly see a somewhat flatter ledge on a steep slope, it could well be the remains of a path and however overgrown it turned out to be true.

Above the basin is an overgrown field with a sparse chalky soil, but there is a huge cairn as a sign that the soil around it was in the past “stone free” and worked. Maybe with hemp?

“In the evening when I see the flock of sheep roaming the hillside, I am back with those diligent survivors.”

Human life in the most unlikely places

For example, there is an abundance of tracks in this area, intersected by valleys, chasms and ravines. A dead cherry tree or a hundred-year-old small-leaved sage plant are direct signs of human life in the most unlikely places, where you can walk along roads built entirely from walls that wind for miles to see how the urge to survive expressed itself in stone wonders.

Nowadays there are mainly pines, but photos from a hundred years ago show a barren meadow area, because wood was expensive and needed for heating, bread ovens and buildings.

Such an infrastructure was of course only possible through shared labor, which you should not imagine too idyllic: they sometimes did not speak to each other for generations because a neighbor’s chickens were found in the vegetable garden, or the water tank emptied overnight, so that a mother could not give her children anything to drink. But if you had to bury a dead horse or a dead villager in winter, there is not much else to chop open on the rock-hard ground.

In the evening when I see the flock of sheep, while sitting on one of those terraces, roaming the hillside, I am back with those diligent survivors, only these sheep give more milk and the sheep cheese is found on every locally well-stocked table.

This is called adapting to modern times without throwing the wealth of tradition into the dustbin of history. Especially the last light and the silence make the landscape timeless.

Teaser Photo: © Valérie Géslin