Ed. note: The following piece is an excerpt from the Free, Fair, and Alive, by David Bollier and Silke Helfrich. You can find out more about the book and read it online here.

Open Source Seeds

For millennia, people have treated seeds as a mystical, sacred source of fertility and nourishment. Out of nothing, it would appear, life begets life. From its inception ten thousand years ago, agriculture entered into an intricate dance with living, natural forces — soil, water, animals, and the entire ecosystem — as a way to grow a rich bounty of food. That web of aliveness is under siege as large multinational corporations try to own and control seeds as much as possible. Since the early 1980s, companies have agitated for far-reaching intellectual property rights over plant genetic resources, giving them new powers to control plant breeding and production. As private ownership of seeds has consolidated into fewer and fewer hands — globally more than sixty percent of commercial seeds is now controlled by four agrochemical/seed companies — it has reduced the biodiversity of germplasm (living tissue from which new plants can be grown), making agriculture more vulnerable to pests, diseases, and climate change. The big industry players are intent upon controlling the basic inputs for food production — seeds, fertilizer, Big Data — to serve the interests of large-scale industrial agriculture, commodification, and profit extraction. This approach is eroding the independent production, stewardship, and biodiversity of seeds.

The concentrated ownership of seeds has radically disempowered farmers. Companies like Dupont and Monsanto use their oligopoly power to impose use restrictions — essentially, legal “fences” such as plant patents, utility patents, Material Transfer Agreements (MTAs), licenses, and use agreements — that restrict what farmers can do with their seeds. A “limited license to use” for example, turns out to mean: no saving the seed, no replanting the seed, no breeding of seeds, no research on the seed, and one-time use solely for planting. The licenses may also authorize the seed company to access the farmer’s land and online crop records to determine which seeds are used where. The seed corporations are not selling seed. They are renting seed for one-time use! Being the legal owner of the seed lies at the heart of this business model. On top of such restrictions, the seed industry legally treats the industrial farmer in the US reliant on 250-horsepower farm equipment in the same way as the campesino in Guatemala with his donkey. Each can use seeds only as specified by corporate licenses, much as software users are constrained by the software industry’s one-sided “shrinkwrap” licenses.

Extensive privatization of seed has resulted in an institutionalized market failure. The global seed market has been captured by an oligopoly of large companies that have thwarted competition, promoted crop monocultures, failed to develop innovations to deal with climate change, and undermined organic local farming. “Corporations have used IPRs [intellectual property rights] over genetic materials not just to accrue monopoly rents, but to actively undermine the independence of farmers and the integrity and capacity of plant science,” writes Jack Kloppenburg, a leading seed activist and professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

The appropriation of seeds raises a profound challenge to farmers and, really, everyone, because we all have to eat. How can we steward the natural gifts of life that seeds provide and overcome the genetic engineering that has made them sterile or nonshareable under patent law, contract law, regulation, and/or court rulings? How can we restore the ethic of seed sharing and popular sovereignty over seeds that has been appropriated by large corporations through market power and the law?

Over the past thirty years, a movement comprised of farmers, agronomists, public institutions, lawyers, and sustainable food system advocates has tackled this question in a number of ways. Most seek to liberate seeds from the artificial constraints of property law. This fight is often blended with fights over land tenure, water rights, gender equality, and other concerns. These issues are important, for example, to two leading organizations in the Global South, La Via Campesina, a network of peasant-farmer and Indigenous groups, and Navdanya, an Indian advocacy group for seed freedom founded by Vandana Shiva.

Despite their different styles and emphases, most of the various seed-freedom players wish to establish a protected commons for seed sharing compatible with the imperatives of living ecosystems. Jack Kloppenburg notes that there is general agreement about the need for four universal rights: to save and replant seed; to share seed; to use seed to breed new varieties; and to participate in shaping policies for seed. The big seed companies generally oppose these rights by invoking legal tools that privilege private ownership of seed biowealth. The political and legal obstacles to seed sharing have led many seed advocates to look to a self-help option: building their own legally protected seed commons. Inspired by the success of the GPL and free and open source software over the past thirty years, some leading players in the seed movement decided to align behind the banner of “open source seed.” With two friendly but separate arms of the movement based in Europe and the US, respectively, the open source seed movement has adopted two general approaches to restoring user sovereignty over seeds: new types of licenses similar to the GPL, and campaigns to create strong community cultures of seed sharing. Both approaches seek to facilitate plant breeding and seed sharing as protected commons.

Just at the time when the huge ag-chemical and biotech companies Bayer and Monsanto merged, OpenSourceSeeds, a nonprofit project of AGRECOL e.V., the Association for AgriCulture and Ecology, based in Germany, launched its own legal response: an open source license that prohibits users from patenting any derivative plants grown from licensed seeds. It also prohibits the use of proprietary protections for plant varieties licensed under open source licenses, and applies these same rights and obligations to any future users of the seed. The Open Source Seed license does not grant exclusive rights in the way that most conventional licenses do; it confers the right to share the seed and any developments or enhancements conditional on fulfilling a duty of making it available for public use. Any follow-on users must then accept the same conditions. The license implicitly applies as well to the genetic information contained within seeds.

Open Source Seed Initiative (OSSI) decided against using legal contracts and enforcement, for reasons of both practicality and principle. OSSI believed that it would be hard to print dense, complex legal licenses on a packet of seeds, and that legal language that might be honored by courts would probably not be understood by most farmers. Moreover, many people in Indigenous and Global South contexts objected to the very idea of legal contracts that define seeds as property. They preferred to base sharing on a peer-enforced social ethic. Finally, many farmers and plant breeders are wary of licenses because, while eager to share seed, they want to retain the right to receive payment for any breeding innovations that they do.

Because of such diverse motivations among growers, the Open Source Seed Initiative decided to promote a vernacular seed law in the form of a pledge: “You have the freedom to use these OSSI seeds in any way you choose. In return, you pledge not to restrict others’ use of these seeds or their derivatives by patents or other means, and to include this pledge with any transfer of these seeds or their derivatives.” The pledge does not have the force of state law and enforcement behind it, but instead looks to the ethical and social norms of plant breeders to model behavior and shame transgressors. Drawing upon the ideas of the GPL for free software, the pledge means that users will treat seeds as openly available to all, and will not assert any private control over them. In other words, it is a pledge not to restrict access or use. Nourishing this ethos is at least as important as complex legal agreements that may or may not be understood by farmers and that may not be practically enforceable in any case. Can a peasant farmer realistically hope to prevail in litigation against Bayer-Monsanto? As of mid-2018, said Kloppenburg, “We have 400-plus varieties, fifty-one species, thirty-eight breeders, more than sixty companies [who have signed the Pledge]. We are there, we are real, we are doing it. And I didn’t think these breeders — public breeders — existed in the USA. Guess what: they do. They are real. They are there, they are surviving. We didn’t create them. We are building on a pre-existing network. This is why OSSI works … because we created connections to what already existed.” Kloppenburg’s comment points to the reality that relationalized property often exists already and doesn’t necessarily need to be created; it needs to be protected, whether through law, social sanction, or norms.

Despite the philosophical and tactical differences between the two open source seed projects, both share a concern with treating seeds as a commons — i.e., as something that does not belong exclusively to any individual owner, but whose value arises precisely because it can circulate freely and be shared. The open source seed movement seeks to affirm seeds as something that has deep, symbiotic relationships with other aspects of the ecosystem and human life as well as to past and future generations. The movement wants to restore the dynamic agency of seeds in living ecosystems, rescuing them from their status as sterile, controlled units of intellectual property. This insight is important not just as a moral claim made by commoners (who are responsible for breeding improvements) and by public institutions (which often finance agricultural research). It is a necessity for our planetary ecosystem and agriculture, especially as climate change intensifies.

Commoning Mushrooms: The Iriaiken Philosophy

Once a community escapes the conventional ideas of property (or never embraces them in the first place), it acquires the capacity to nourish new types of relationships, both within a commons and beyond its immediate boundaries. Stewarding seeds as biowealth deepens the interdependencies between human and nonhuman life. One inspiring example is the traditional Japanese right to common known as iriaiken. Its root, iriai, literally means “to enter collectively.” Iriaiken is “the right to enter collectively.” Iriaiken usually refers to the collective ownership of nonarable areas such as mountains, forests, marshes, bamboo groves, riverbeds, and offshore fisheries. From the 1600s through 1868, villagers in Japan allowed people to collect wood, edible plants, medical herbs, mushrooms, and more, but only if they followed rigid, peer-enforced regulations for usage.

In practice, iriaiken translates into many different, context-specific forms of collective ownership. There was sòyù (joint rights) and gòyù (joint ownership), for example. The most common type of the latter was called mura-mura-iriai, meaning “collective ownership of an area by the inhabitants of several neighboring villages.” This is intriguing because unlike most European commons that dealt with a specific human settlement and piece of land, the rights of an iriaiken extended to several villages, not just one. They were regarded as integral to the region and could not be divided up among villages. Thus the rights to common were not executed by the villagers of a village but by a federation of villages!

In the Meiji period of the late nineteenth century, when a new legal code was adopted and modern legal principles were introduced, the right of villagers to common was not abolished, but acknowledged as a rule of custom. So in modern Japanese law iriaiken is still recognized. It is defined as having the nature of joint ownership. Not surprisingly, the two conceptions of law — modern law and the law of the commons (Vernacular Law) — have come into conflict, especially on matters of property rights. The more that full private ownership of land and exclusive land titles were recognized, the faster the decline of iriaiken-style property regimes. But even today we can find iriaiken-based property arrangements in Japan. One of the most intriguing examples can be seen in the stewardship practices of matsutake mushroom gatherers in Japanese villages.

Matsutake are delicious wild mushrooms that grow in forests and cannot be artificially cultivated. This is partly why they are very expensive. Some Japanese varieties regularly sell for more than US$1,000 a kilo, with especially rare ones going for $2,000 a kilo. Annual harvests of matsutake peaked in the 1950s and have declined steadily since then, mainly due to two factors: the decline of their habitats (especially from a disease afflicting Japanese red pines, with which matsutake is associated) and the decline of traditional harvesting practices such as collective harvesting, undergrowth clearance, the thinning of forests, and the gathering of leaf litter as fuel or fertilizer, which once helped improve growing conditions for the mushrooms. Interestingly, forests that are hospitable to matsutake mushrooms tend to be disrupted, scarred landscapes with young trees. They are often full of human traffic, especially for gathering matsutake, explains anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing in her acclaimed book, The Mushroom at the End of the World. The presence of human visitors “keeps the forests open, and thus welcoming to pine; it keeps the humus thin and the soils poor, thus allowing matsutake to do its good work of enriching trees,” she writes.

Kyoto Prefecture in Japan has been famous for its matsutake production. It is there that a unique traditional auctioning system for matsutake gathering developed in the seventeenth century, at Kamigamo shrine in 1665 in the first instance, before being adopted by almost all villages in the prefecture. Two centuries later, in response to the privatization and dividing up of communal forests during the Meiji Period, villages adopted holistic bidding systems, reinterpreting the iriaiken spirit in modern times.

The core of the holistic bidding system is difficult for the modern mind to grasp because harvesting rights do not correspond to property ownership. As the anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing explains, “[E]ven if a villager owns a matsutake-yama (a forest or mountain where matsutake grows), he must bid for the right to harvest the matsutake growing on that land … and those who do hold the exclusive rights to the gathering and selling of matsutake … change from year to year through the bidding process.” This means that the owner of a plot of land is not allowed to harvest mushrooms that grow on that plot of land. Yet at the same time, neither is the owner absolutely forbidden from harvesting mushrooms because he or she may win that right through the community’s bidding process.

How is that possible, and what does that mean? The answer lies in the iriai philosophy and more concretely in the way villagers conceive the interconnectedness of the whole system. They see deep interconnections among the mostly invisible matsutake rhizomes in the soil with the mushrooms that grow on the land, and the relationships among the villagers and owners of different plots of land, among other relationships.

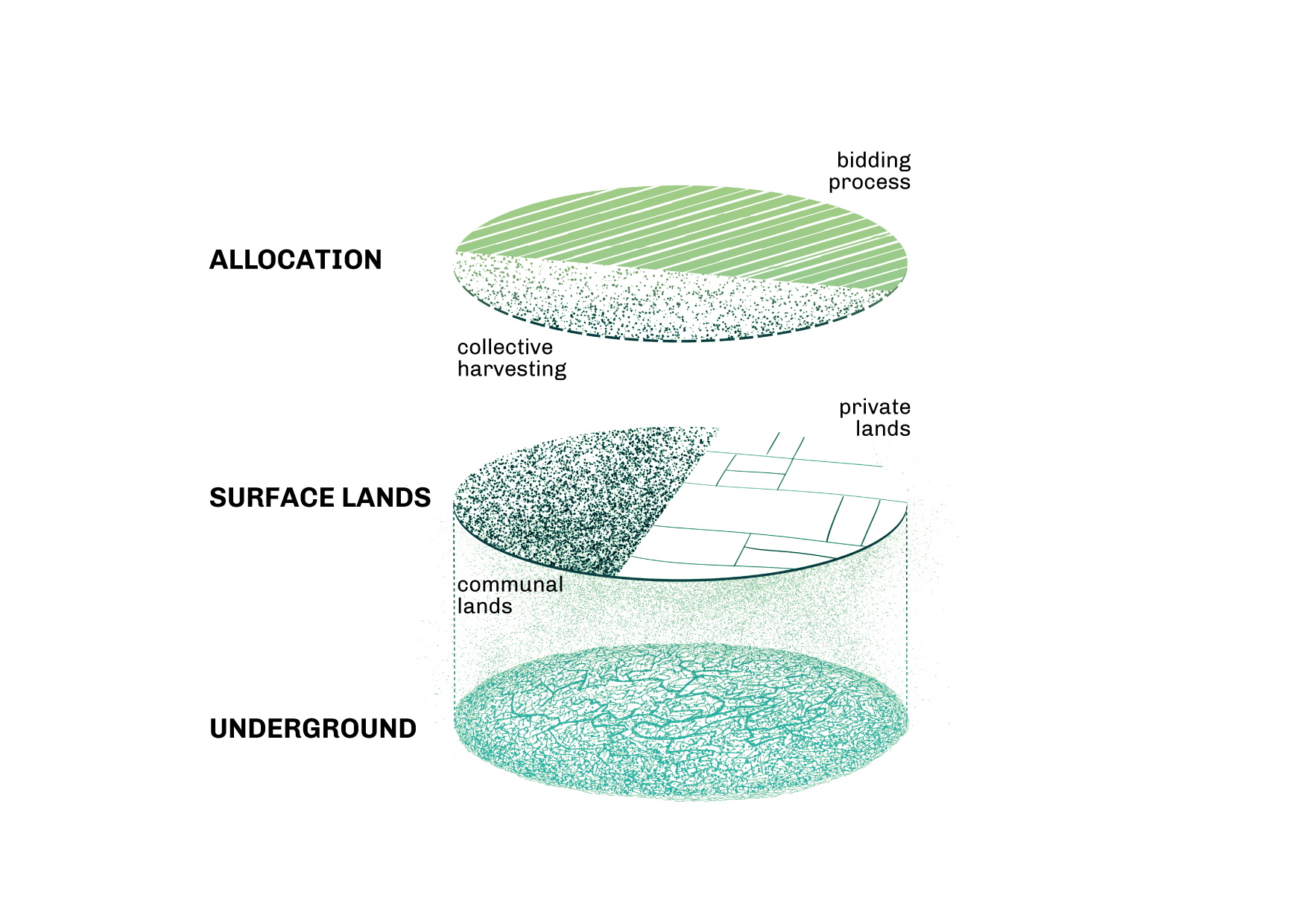

We can see one way in which the bidding process plays out in the village of Oka in Kyoto prefecture, where the iriai philosophy has always been strong. The basic challenge faced by villagers is how to aggregate and share mushrooms that are distributed unevenly across many different plots of privately owned land. The mushrooms are regarded as shared wealth because they arise naturally, without anyone’s active cultivation, and because the mushroom roots are a vast underground system that sprawls across the entire village, without regard to property boundaries on the surface. So the problem is how to allocate biowealth that is seen as both collectively owned (in the subsoil) and privately owned (on the surface) in a fair and equitable manner.

The villagers’ solution is an auction. That name is a bit of a misnomer because the bidding system is not used to raise money to grow the mushrooms in the first place, as members of a CSA farm might do for the upcoming crop. Rather, the auction helps assure that everyone gets some benefit from the mushrooms, either through direct harvesting, allocations of mushrooms reserved for collective use, or through community income.

The first step is to divide the whole terrain into five parcels without regard to anyone’s formal land ownership rights. Then, as in other villages, Oka auctions off gathering rights for three of the five parcels. The two remaining parcels are reserved for weekly Sunday expeditions by members of cooperatives established for managing the matsutake. “All participants climb up to the forest at the same time and gather matsutake together. In 2003, the highest daily amount harvested jointly was twenty-eight kilograms (about sixty-two pounds). Afterwards, the harvested matsutake are assembled and distributed to all participants in equal amounts, except when they are reserved for a joint feast…” A nice example of Pool, Cap & Divide Up. To make things fairer (and more complicated), the two types of parcels reserved for community use rotate every year. Thus a parcel that is bid out one year may be reserved for joint harvest the next year. Only cooperative members are allowed to participate in the bidding meeting and in joint harvesting activities.

Any villagers can participate in the bidding process, through which the community assigns harvesting rights to the highest bidder. The winner then holds exclusive rights until November 15, when the game hunting season starts. “During this time … no one, not even the land owners, can walk in their own forest even if it is not matsutake-yama, without permission,” write Saito and Mitsumata. “If they try to even get near the forest area without permission, they may be suspected of being a matsutake thief.”

The purpose of the bidding is to get the mushrooms on private lands into a common pot that can be reallocated for community benefit. In essence, it’s a scheme to monetize three-fifths of the annual mushroom crop from sales to villagers only, and to apply all income from the bidding on activities and tools that improve the matsutake habitat. The bidding process is thus not like a normal auction. Because villagers agree that the mushrooms cannot belong to anybody exclusively, the auction provides a way to redistribute the anticipated income from selling matsutake to benefit all villagers. The partial monetization of the annual crop lasts for only one season, and it is used to benefit the village and mushroom ecosystem over the long term.

Communal income from matsutake harvesting in Oka fluctuates from years to year. But in a 2004 study, the village collected ¥329,000 in 2003, or about US$9,087. This income is not divided up among members, but is used to pay part of the cost of a group tour/celebration each year. In other communities it has been used for improving the infrastructures or education in the communities. In Oka, since 1962, all members practice what is called deyaku, compulsory work days, very similar to the famous minga system in Andean countries or irrigation ditch maintenance in acequias in New Mexico. Villagers can choose a preferred day from two designated days for deyaku. If a member doesn’t participate, a ¥7,000 penalty is levied, but the coop rarely needs to sanction anyone. The joint harvest activities and denyaku work to Ritualize Togetherness and forge a sense of community. When in 2004 researchers participated in the compulsory work sessions, “the work that day was easy and a sociable atmosphere prevailed — the female participants especially enjoyed talking to each other, and a break was held every thirty minutes.”

The core idea of the holistic bidding system — that the owner of a specific plot of land is not entitled to harvest the matsutake that grow on that land by dint of ownership — is similar to laws that govern many individual forest owners in Europe who cannot simply decide on their own to cut a tree on their property. Villagers obviously have a particular understanding of who owns what — a multilayered tableau of protocols, as it were, for treating the world. Landowners consent to this arrangement because it is a traditional community arrangement; they see themselves as co-designers and co-decision makers of this process as part of the community. Community-regulated access is not seen as a prohibition, but rather as a sensible consensual agreement — obviously, a cultural shift from the Western, proprietary mentality. According to the researchers, “at a subconscious level,” the land belongs to the whole village.

Common land coexists with private rights. In harvesting matsutake mushrooms, Oka villagers regard the underground soil in which the mushroom fungi grows as commonly held land that cannot be alienated or privately owned. On the surface of the land, peer governance determines how people may access the mushrooms.

Common land coexists with private rights. In harvesting matsutake mushrooms, Oka villagers regard the underground soil in which the mushroom fungi grows as commonly held land that cannot be alienated or privately owned. On the surface of the land, peer governance determines how people may access the mushrooms.

This understanding illustrates a larger point about property itself —that “private assets most always grow out of unacknowledged commons,” as Tsing writes. “The point is [that] privatization is never complete; it needs shared spaces to create any value. That is the secret of property’s continuing theft … The thrill of private ownership is the fruit of an underground common.”

One must wonder why this ethic should not also apply to the extraction of coal, gas, and oil from deep underground. There is obviously a difference between the value of that which exists in the ground, untouched and prior to any human activity, and the costs of exploring, mining, drilling, and refining — that is, the costs of making it available to human use. This is a serious difference. But consider what our economy might look like if the full value of oil could not be privately appropriated by corporations or by the nation-state simply because they drill it. The only economic return would be on the work invested to extract oil and refine it into useable fuel. The rationale for such a property scheme is simple: oil and minerals were formed over millions of years without any human contribution, so why should any private party be able to own them? This is the exact logic that Oka’s matsutake commoners have put into practice — a fair, ecologically minded way to steward the wealth generated via their shared underground wealth.

In recent years, the iriai system has come under siege, particularly by younger people who don’t work in the villages and, not surprisingly, by those who own matsutake-yama where the mushrooms grow. In the villages of Kanegawachi and Takatsu, the classical Lockean arguments have been made, that “every landowner has the right to the fruits of his or her land on the one hand, and ought to pay a fixed asset [property] tax on the other.” It has been argued that these customs don’t guarantee “enough rights to matsutake-yama owners,” and that they have therefore created “a disincentive to landowners to carry out the habitat improvements needed to enhance matsutake production.”

These assertions are groundless, however. No evidence to support them has been brought forward. In fact, the evidence points in the other direction: the most serious habitat improvement projects in the Kyoto region have been sponsored by the Association for Promotion of Matsutake Production of Kyoto, with help from government subsidies. Seven years later, a survey on improvement activities noted efforts “on 405 sites totaling 310 hectares in 15 districts, and in almost all cases the sites were communal forests as opposed to privately held lands.” This makes perfect sense because habitat improvement requires specific knowledge, regular activity, and patience. Most individual land owners, in contrast, discontinued their improvement efforts after a year or two. As the evidence suggests, there are not only philosophical but very practical reasons for treating the matsutake-yama as wealth to be owned and managed by the whole village.

According to the research, the decline of the iriaiken land use system has had negative effects on both village finances and matsutake productivity. Villages that chose other systems than Oka — e.g., allowing owners to harvest on parcels of their choice by paying sixty or seventy percent of the bidding income — have now had to introduce membership fees or other taxes to boost village revenues and maintain village infrastructures. Kanegawachi is such a case. Since the holistic bidding system was turned into a piecemeal bidding system in 1999, “bidding income has declined by more than 75% — from 250,000 Yen in the early 1990 to 60,000 Yen in 2004.” At the same time, the willingness of matsutake-yama owners to work to improve matsutake habitat has declined and a vicious circle of individual exploitation has arisen. This stands in stark contrast to the virtuous circle of the Oka villagers who common matsutake.

The Oka story tells us a great deal about how property, typically seen as a right of absolute dominion over a bounded object, can be re-imagined in socially minded yet practical ways. But this is not just a matter of enacting a state law or regulation; it requires a cultural ethic that can only be cultivated through social practice and agency. There must be a commitment to the shared ecosystem and infrastructure upon which everyone depends while also providing space to nourish social relations and human/nonhuman relationships. Notably, this does not preclude individual usage rights or even the right to sell a renewable resource. Perishable mushrooms, for example, can be treated as usufruct, which is the right to use something that belongs to someone else so long as the underlying resource itself is not diminished.

In a larger sense, the matsutake story demonstrates the virtues and practicality of relationalizing property. It is entirely feasible to use property to strengthen social and ecological relationships rather than rend them asunder through ownership and capitalism. Just as the peculiar history of the Nidiaci Garden (pp. 207–209) showed us how a single plot of urban land can be treated as both private property and public property, each with different outcomes, we can see in the matsutake story that managing land as a commons allows for qualitatively different kinds of value to emerge. That value is at once personal, social, and ecological, as well as economic. Things can belong to us as individuals and as part of a collective at the same time. Property arrangements can be designed to respect our freedom-in-relatedness to use things, fairness in providing wider access and use of them, and vibrant living communities as effective forms of Peer Governance.

Teaser photo credit: By Tomomarusan – This is the creation of Tomomarusan, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=600727