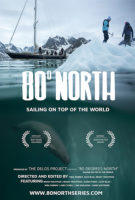

80° North: Sailing on Top of the World

80° North: Sailing on Top of the World

The Delos Project presents a four-part docuseries produced by Brian Trautman, Karin Syren and Brady Trautman; directed and edited by Kiril Dobrev, Alex Blue and Brady Trautman; cinematographed by Alex Blue, Brady Trautman, Kiril Dobrev, Brian Trautman and Karin Syren; music by EpidemicSound.com; still photography by James Austrums, Alex Blue, Kiril Dobrev and Joachim Haesendonck; drone piloting by James Austrums, Brian Trautman and Andy Schell; narrated by Gunnar Magne; audio Mixing by Nature of Noise; animations by Animations Outsourced. Running time: about 30 minutes per episode. Available to view at: 80northseries.com.

80° North is part sailing adventure, part beautifully photographed travelogue and part eyewitness account of the environmental threats faced by the Arctic. The four-part docuseries tells the story of eight plucky individuals who sailed to the top of the world (to paraphrase the series’ subtitle) and recorded their journey for the rest of us to share in vicariously. We watch with trepidation as they brave frigid temperatures, scale sheer ice cliffs and navigate through treacherous iceberg minefields. We share their amazement at seeing wondrous creatures in their natural habitats. And we feel their sadness in documenting the extent of humankind’s presence in the Arctic.

Their three-week expedition took place two years ago and brought together two pioneering sailing crews for the first time. One crew had already been documenting its travels since 2010 on its popular YouTube channel Sailing SV Delos. The other had been operating an offshore sailing adventure company called 59° North Sailing since 2015. Their shared passion was the pursuit of sailing as a full-time vocation and a model of self-sufficient living. The seed of their joint venture was planted when 59° North cofounders and husband and wife team Andy Schell and Mia Karlsson first met and bonded with the Delos crew in Stockholm, Sweden. Schell later reconnected with Delos captain Brian Trautman to let him know that he (Schell), along with Karlsson and ship’s photographer James Austrums, planned to sail around the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard the following summer, and to ask if the Delos crew would join them. Neither crew had ever sailed the Arctic, but Trautman and company enthusiastically accepted the challenge.

Though Schell initially pitched the trip as fodder for a future episode of Sailing SV Delos, it would take on a life far beyond the YouTube space, and would draw on the documentarian talents of 59° North just as much as it would those of the Delos team. Austrums’ gift for still photography, together with his and Schell’s experience piloting camera drones, would prove a perfect complement to the Delos crew’s video blogging prowess. The result is a work of filmmaking that engages as much as it educates, and awes with wonderful regularity.

As we meet the eight courageous individuals who have ventured aboard Schell and Karlsson’s 1972 Swan 48 Isbjörn, the tone is an enchanting mixture of idyllic and playful. A leisurely tracking shot reveals a secluded cove, its obsidian waters surrounded by steep white cliffs and wisps of cloud. A drone shot swoops over an expanse of majestically etched ice spires that dwindle to obscurity just beneath a mountained horizon. Then we’re aboard the Isbjörn in time to see each member of her crew take a rejuvenating plunge into the near-freezing ocean at the urging of Captain Schell, who somewhat jestingly extolls the virtues of becoming “one with the cold.” A chorus of pained as well as delighted squeals fills the air as they dive.

It doesn’t take long for the docuseries to temper this initial merriment with sober reflection on the challenges ahead. The captain who at first seemed carefree goes on to reveal that he’s acutely aware of the responsibility he bears for his crew’s safety, and that he expects this awareness to make him “on edge” for the duration of the trip. He knows theirs is a passage that not many have attempted by sail, and he quotes a blunt saying about the region through which they’ll be traveling: “The Arctic will kill the unprepared.”

Among the potential dangers that have Schell ill at ease are freezing temperatures, the notoriously fast-changing Arctic weather and ice floes capable of crushing ships. The cold and wind make finding safe anchorage a challenge, necessitating around-the-clock watches each night to ensure the spot where they’re anchored remains secure. The sailors must also be on alert for small fragments of glacier ice known as bergy bits and growlers, which are smaller than icebergs but are still more than capable of wrecking a boat hull.

And whenever our adventurers come ashore, they face the risk of polar bear attacks. Prior to departing, the team stops into a gun shop to rent a big-game rifle and receive a crash course on its use, just in case they need protection from a hungry bear. We’re informed that Finnish law requires people in Svalbard to carry flare devices when traveling outside settlements, for the purposes of scaring off confrontational bears, and that it recommends carrying rifles as well. Thankfully, while the crew does catch some fine footage of a mother bear and her cub, they never experience an encounter that would call for breaking out the gun or the flares.

The first hint of tragedy comes during episode two, when we happen upon a throng of walruses sunning on a beach and learn about the injustices inflicted on these calm giants. We’re given a brief history of the walrus-harvesting industry of the 18th through early 20th centuries that nearly drove the animals into extinction. (And though the docuseries doesn’t get into this next topic, we now know that the hunting ban of 1941 in no way put an end to the abuse, as evidenced by the high levels of heavy metals, polychlorinated biphenyls and other human-made contaminants found in the bodies of present-day walruses.) Yet as somber as this segment is, it contains some of the docuseries’ best wildlife photography.

Equally enrapturing are the team’s video footage and audio recordings of beluga whales. There’s a nice aerial shot of a pod swimming in synchrony, followed by a hydrophone recording of beluga songs that amply demonstrates why these creatures are referred to as the canaries of the sea. The calls relayed through the hydrophone are a medley of clicks, chirps, bleats, squeaks, whistles and other astonishing sounds. And as with the walruses, we feel grateful that the marvelousness of these animals is still around to be appreciated, in spite of the grievous casualties wrought during the halcyon days of commercial whaling.

The signs of humankind’s ever-growing toll on Arctic ecosystems are ubiquitous. Because the Arctic happens to be disproportionately affected by a number of environmental threats, it provides an especially sharp lens through which to view their extent and gravity. As our travelers comb the beaches of Svalbard, they see plastic everywhere, an interminable trail of toxic detritus that speaks volumes about the shortsightedness of human beings and the interconnectedness of our world. Evidence of climate change pervades every aspect of the expedition, beginning with the fact that it was feasible in the first place. As Schell explains, it’s only because of the extreme loss of Arctic summer sea ice in recent years that a trip like theirs is possible, since an icier Arctic is one in which no navigable routes around Svalbard exist.

We also see how the newly thawed waters are luring cruise ship traffic, a development about which our protagonists express mixed feelings. One opines that while the rise in visitors does impose an undue burden on local communities, it’s good that more and more people are getting a chance to witness the effects of climate change firsthand by coming to the Arctic on cruise ships. Another recounts a vexing exchange with a cruise ship captain. The captain warned them all that they were in violation of laws governing interaction with wildlife, though a subsequent review of these laws revealed no such offense. It’s suggested that the captain may have been trying to deceive them in order to guarantee his own party priority access to areas where the Isbjörn crew had been spotted walking or swimming.

The stories of how 59° North’s founders and the man behind Sailing SV Delos managed to turn sailing into a career are amazing but beyond the scope of 80° North. For instance, while the docuseries gives a bare-bones outline of SV Delos founder Brian Trautman’s journey from software analyst to groundbreaking nautical entrepreneur, it doesn’t get into his boat’s onboard spirit distillery, the travails of trying to repair engine parts at sea or the brushes he and his crew have had with Somali and Indonesian pirates. (I learned these details from a Wall Street Journal feature on Trautman that I read after watching the docuseries.) With luck, a future series will get us better acquainted with this fascinating group of uniquely accomplished sailors.