From the Strong Towns website:

In the run-up to November, we talked a lot as a staff about what to publish during election week. On the one hand, we didn’t want to run a bunch of extended, hard-hitting content when the nation’s attention would, naturally, be elsewhere. On the other hand, we sure as heck weren’t going to be silent. Then Daniel proposed this essay in one of our weekly pitch meetings, and it seemed like the perfect fit.

At Strong Towns, we’ve always been sincerely dedicated to working across political barriers. The Strong Towns approach is one that we know can unite people of all sorts of ideological persuasions, and one that makes all our communities better—no matter in they’re in red or blue states. And the truth is that few of us really live in “red” or “blue” areas anyway. We live on streets and in neighborhoods filled with people who have a myriad of political convictions, many of which—despite what Twitter might tell you—do not fit neatly into a Democrat or Republican box.

What Daniel writes in the following essay about political divisions and caricatures and—most importantly, how to move past them—is essential Strong Towns reading. I urge you to absorb and ponder every word. — Rachel Quednau, Program Director

This piece is being published on Election Day 2020, so as of this writing I don’t know what’s going to happen next week, month, or year. The current moment provides plenty of doomscrolling opportunities if you want to read the likes of an in-depth exploration of whether America’s coming armed conflict will look more like Northern Ireland 1972 or more like Syria 2011. Yikes. (For the record, I still think there’s plenty of reason to believe we’re not going to see as dire a state of unrest as either of those. But yes, there’s been political violence in 2020, and it seems hard to imagine there won’t be more.)

No matter the outcome, tens of millions of Americans are going to feel betrayed, cheated, and frightened. It’s difficult right now to see a way back from polarization. One thing is certain: there is no way back whatsoever that involves ostracizing 30 or 40 percent of the country and permanently excluding them from power, in 2022 and 2024 and 2026 and so on. The idea that that is possible is pure fantasy. The people you think are too propagandized and deluded to reason with aren’t going anywhere. And so we have work to do in learning to hear and understand each other, the better to be heard and understood.

I think I have some basis in feeling like I can talk about this subject because of my experience with Strong Towns.

Strong Towns has always sought to be a voice that cuts through the noise of our heavily ideological national politics and media cycle. We’re not a centrist or “moderate” movement. We attract a politically eclectic group of readers and members, I believe because the truths we have identified largely exist outside of the left-right axis of American politics. There are people at every part of that spectrum who care about building local resilience. The Strong Towns approach is radical, but not in a way that fits into ideologues’ narrative boxes.

We routinely hear from candidates for local office who identify with the Strong Towns movement. One thing that has surprised me is that, to hear them describe who they are and their priorities in their own words, I can rarely tell which political party they identify with. In part this is because our issues map poorly onto the left/right divide. But it’s also simply a reflection of the fact that generalizations about what large groups of people value and believe fall apart in the specific. Individuals in their communities are just that: individuals, with unique perspectives and motivations. It’s why local politics tends to be where the process is most cooperative and least dysfunctional.

A World of Cartoon Villains

Scrolling social media is an entirely different world. Lately, it’s been full of ugly caricatures of the kinds of things real people supposedly think. It’s as if we inhabited a world made up of scheming, cackling cartoon villains, not real people.

Things I’ve actually read recently, without exaggeration (in case it needs to be said, and I fear it does, not one of these is true):

-

“Republicans don’t care if you die.”

-

“Democrats support the looting and burning of cities.”

-

“The GOP is composed of people who don’t think I should have basic human rights.”

-

“Democrats will happily destroy the economy just to make Trump look bad.”

-

“You can’t be a good person and vote for [Candidate or Party Name Here].” (I’ve seen every version there is.)

Here is a challenge that can benefit everyone, in two parts:

1. Expunge the vague, unspecified “They think” and “They want” from your political vocabulary. Are you appalled by something an opposing political faction seems to believe? Okay: find an individual who voices the sentiments you hate. Who are they a spokesperson for? Whose views do they credibly represent? How do you know?

2. When you’re about to voice public disagreement with someone’s views, first write down (for yourself) a description of what that person believes. Then ask yourself, “Am I describing this person’s opinion in language they would agree with or at least accept?”

No? Try again. Amend it until you can confidently answer, “Yes.”

My guess is you will often fail, or resort to caricature. How many of us can actually describe the views of people we vehemently disagree with in language those people themselves would endorse?

I’m describing an exercise in understanding, which is not the same thing as agreeing, conceding, endorsing, excusing or forgiving. It does not mean that you must practice both-sides-ism, the lazy fallacy that says that if there appear to be two extremes on a subject, the truth must lie somewhere in the middle. Sometimes it doesn’t, and you are perfectly free to conclude that it doesn’t.

You’re free to think what you think, for the reasons you think it. Which means you should grant others the same: the right to their own reasons.

An essay by Laurie Penny on the political symbolism and meaning of the “family” contains the following statement:

“The ideal of ‘the family’ that conservatives want to protect is an ideal of white male supremacy. It has nothing to do with helping actual adults and children to love and protect one another. It is, in fact wholly uninterested in human happiness. Instead, it is concerned with human obedience, particularly female obedience.”

Full disclosure, at the risk that some of you will want to stop reading when you learn this—please don’t!—is that I align with very liberal social views, and I am not a religious person. I wholly agree with the expansive and less tradition-bound version of the “family” that Penny would like to see enjoy social approval and legal protection.

What I cannot agree with is Penny’s caricature of conservatives. Find me a remotely non-fringe conservative who would agree that they are “uninterested in human happiness” and just want wives and children to be obedient. I’ll wait.

The Stakes of Politics Are Real. Caricatures Don’t Help Us Address Them.

Cartoonish caricatures of those who “aren’t like us” and “don’t share our values” are nothing new in history. They are seductive because they offer easy answers to an eternal human question: why is it that good people so often suffer at the hands of others, or of impersonal rules and institutions those others have designed? Let’s grapple with that question sincerely, because the most common objection I hear to the claim that we’re mostly decent people across the board is, “Well, if they were actually decent people, they wouldn’t vote to do [thing that hurts me or my loved ones].”

There’s a condescending genre of “Let’s all get along” rhetoric, popular on social media, that says we shouldn’t be hurt or offended by something as trivial as politics. “What, you can’t be friends with someone just because they vote for a different party?” This sentiment tends to be voiced by people who have enough security in their own personal situation that they are free to treat “politics” as abstract sport, or an intellectual exercise.

The reality is that politics can be life or death: for many people, basic questions of safety, well being, liberty and autonomy are at stake. It is profoundly condescending and unreasonable to tell people, “You shouldn’t harbor any hard feelings toward someone who voted for a policy that does measurable harm to you.” You’re human. Of course you will.

Demonization, though, is where we need to draw the line. The other side can be wrong, but if you believe they are categorically evil, it is you who are mistaken.

I’m asking you to do the difficult, uncomfortable, but ultimately far more gratifying work of understanding how basically decent people end up supporting, enabling, or voting for things that you find self-evidently bad.

To understand someone means grappling with the roots of their worldview, not just a single idea or set of discrete facts. We do not form our political opinions in a vacuum, and we do not usually form them rationally based on a dispassionate look at the evidence, or even as an outgrowth of our values (though we may flatter ourselves into believing we have). We form them, most often, as an outgrowth of our community—as a key to belonging and forging the mutual solidarity we need to cooperate.

This is not all bad, in and of itself. Group solidarity is essential to survival. What’s bad is when ideas that first served to bind us closer into supportive communities end up hardening into ideology.

An ideology is not the same thing as a worldview or belief. It is prescriptive rather than descriptive: it substitutes its own tidy, self-contained narrative for the messiness of reality. Hannah Arendt, the political philosopher who sought to explain how whole societies succumbed to totalitarianism in the 1930s, understood that ideological fanaticism thrives in the vacuum left when we cease to have meaningful connections with others. Ideology, writes Arendt biographer Samantha Rose Hill, “turns us away from the world of lived experience, starves the imagination, denies plurality, and destroys the space between men that allows them to relate to one another in meaningful ways.”

Arendt could explain even the Third Reich without concluding that Germans were demons. And they weren’t; to see that we need only observe how the very same society, made up of most of the same individuals, rapidly transformed after the war, once the fever of Nazi ideology broke.

Hardened ideologies, filter bubbles, the blurring of news and propaganda, our increasing lack of exposure to those who think unlike ourselves: these things can help explain the state of us in 2020. Cartoon evil cannot.

How to Care About Other People

There’s an article that has circulated for several years on social media in liberal and left circles. It’s titled, ”I Don’t Know How to Explain To You That You Should Care About Other People.” It’s a bad, condescending article that relies heavily on cartoon-villain caricature in lieu of reasoned argument. But its viral success is, of course, not because it’s persuasive, but because it’s an emotionally cathartic experience for those who already share its author’s frustrations. (And an incredibly alienating read for those who don’t.)

I share many of that post’s author’s policy preferences, and yet I know that those who don’t share mine still care about other people just fine. This knowledge deprives me of the satisfaction of a cartoon narrative, and forces me to live in the more ambiguous territory of the real world.

In the real world, simply “caring about other people” is not going to lead us all to agreement on a political program. Not only because there is real ambiguity about whether many well-meaning policies will produce their intended results. Also because “care” isn’t something we simply have or don’t have: it’s selective and situational. As good a thing as “caring” is, trying to sustain empathy for everyone and everything in the world that is deserving of your care is an impossible feat. You would be paralyzed with inaction, and you would likely slip into a deep depression.

In practice, we wield our empathy more like a spotlight, which illuminates the object of its attention, but leaves everything surrounding its circle of illumination in even greater darkness than before.

How can you be a good person and vote for a policy that is going to do direct harm to me? The answer may be quite simple: Not because I wish harm upon you or feel any malice at all, but because you are outside the spotlight of my empathy. I haven’t felt what you feel. I haven’t deeply considered how you will be affected. Or I have, but it carried less weight for me: it faded into the background when placed against the effect on someone closer to the center of my circle of concern. If so, that is my failing, but it is a universal human failing.

We Live in a World We Have to Share

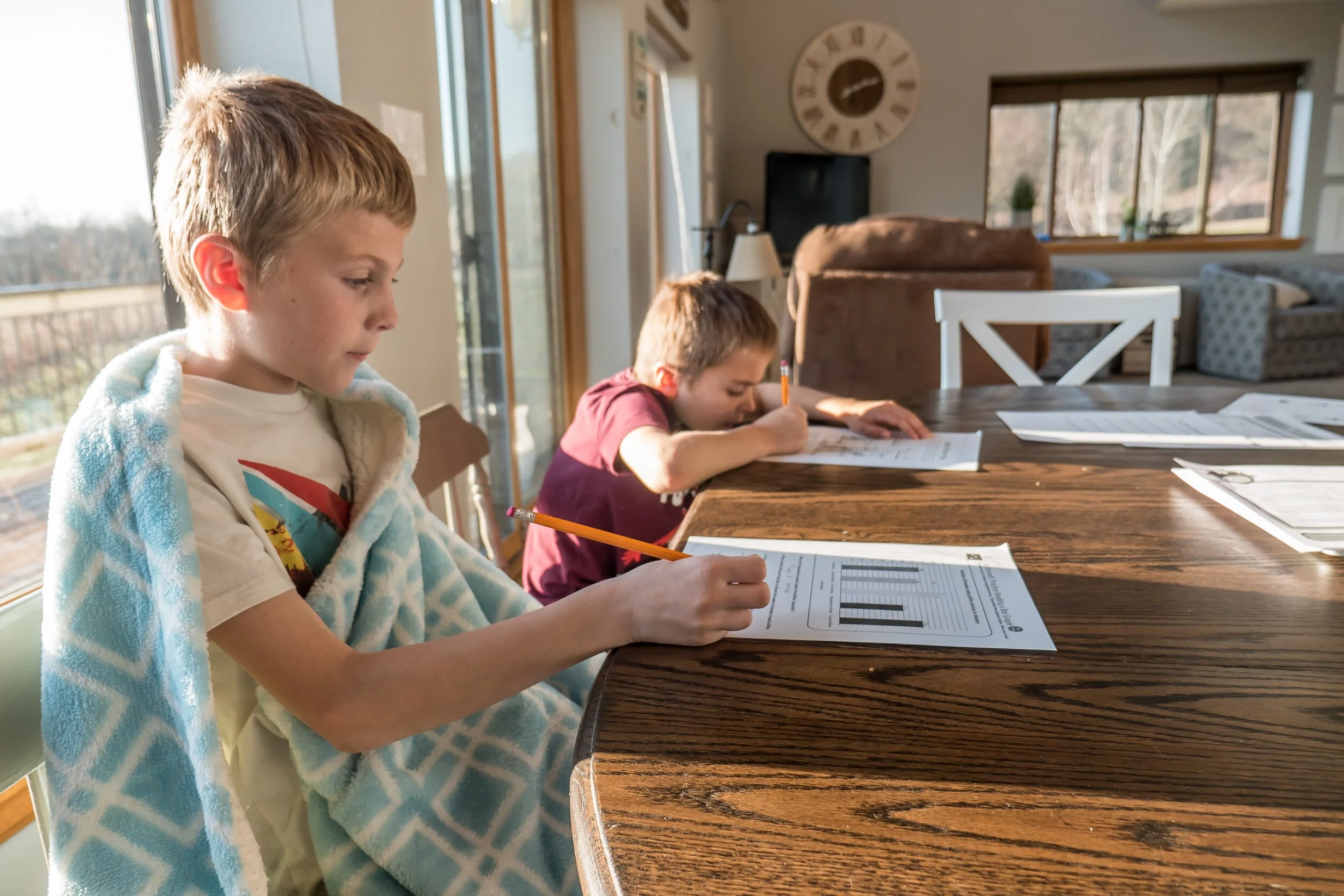

Image via Unsplash.

As a private tutor for the last 12 years (my moonlighting gig), I’ve been inside hundreds of family homes. Most are happy homes that remind me a lot of the liberal one I grew up in, where kids talk back to their parents and put off their homework, where the family is kind and considerate toward me and each other, offers me a glass of water each time I arrive and a paper plate of Christmas cookies to take home at the end of the fall semester. I know that many of my students’ families identify as conservative—you can’t help but spot a yard sign or a bumper sticker. Were it not for those hints, I generally wouldn’t be able to tell before getting to know them.

Because I know and like these people, I don’t have the luxury of believing they are cartoon villains. The same goes for my colleagues with whom I disagree politically. Not everyone is in a position to like or trust the people in their life with whom they have profound disagreements, and I respect that. But I think those of us who do have warm relationships across political divides carry the responsibility of building bridges.

Entering into difficult political conversations is something to do only when we have reason to believe that the situation, the timing, and our approach to the conversation will lead to both parties coming out of it feeling like they had a good interaction and were respected. Even if you don’t think the other person’s views deserve respect, even if all you want is to change their mind, this is the only effective way to do so. No one has ever had their mind changed by someone they didn’t want to change for, or someone they felt looked down upon them.

We live in a world we have to share. The other side isn’t going anywhere.

At the local level, we all understand this, which is why local politics often lacks the entrenched hatreds and toxicity of national politics. The simple fact of your being my neighbor, even if I disagree with you, tends to lead me to include you in my in-group, or circle of moral concern (to borrow a term from philosopher Peter Singer).

Outside of the in-group is where cartoon villains await. I challenge you to broaden your circles of concern. Seek to understand—not agree with or embrace—the roots of a worldview you find incomprehensible or abhorrent. Shine the spotlight of your empathy somewhere you haven’t shined it in a while, and see what you find.

Not because political differences don’t matter, but precisely because they do. It is in the fog of mutual incomprehension that we become capable of being truly cruel to each other. And it is when we move out of that fog that we get the pleasure of working to build great small things together instead.

Image via Unsplash.