KYKOTSMOVI VILLAGE, Arizona – Some 30 years ago, when Navajo Nation member Nicole Horseherder returned to her Native land after college, her hopes of building a home like her grandmother’s near here were dampened because wells had dried up with massive coal strip mining and power plant development that drained the underground water tables while polluting Diné and Hopi communities.

Horseherder found herself shifting in the saddle. Instead of teaching school as planned, she began campaigning for restoration of clean water, land, and air in this Navajo-Hopi ancestral indigenous territory, which is known as the Four Corners area because the boundaries of Arizona, Utah, Colorado and New Mexico states meet here.

Having founded the non-profit Tó Nizhóní Ání (Beautiful Water Speaks) in 2001 for that purpose, Horseherder was glad to receive the news of Arizona Public Service Company’s proposed Just and Equitable Transition assistance package to the Navajo Nation.

She responded to the utility giant’s announcement with a written statement from her organization, which claims Kykotsmovi as its mailing address.

“APS is just one of a number of utility owners and beneficiaries of Navajo coal and water. With the precedent that this agreement sets, it signals to the others that they too have a corporate responsibility to assist the people and communities that helped make the companies so profitable.”

If the state regulators at the Arizona Corporation Commission approve the terms, that will provide a minimum of $127 million from Arizona’s largest electric utility to the largest tribe in the United States over the next 10 years to compensate for the legacy of the coal industry’s debacle in the Southwestern United States.

The industry that created Arizona’s urban prosperity and provided Navajo and Hopi jobs at the cost of Native health and resources is closing the Navajo Nation’s Kayenta and Black Mesa coal strip mines under local and global pressure from climate justice lobbies. It is switching to more reliance on alternatives, such as cheaper natural gas and the renewable technologies that Horseherder’s rural organization has tirelessly advocated for more than a decade.

The “signal” is apt, as progressives rally for a Green New Deal to address climate change in the impending administration of President-elect Joe Biden, and President Donald “Lame-Duck” Trump’s outgoing EPA brass announces its decision not to require coal industry cleanup bonding.

For some time, Horseherder, her husband and three daughters have lived in a home powered by solar energy, independent of the electrical transmission grid. But she wants the many other people who still lack electricity and running water to have access to appropriate technology in the wake of their sacrifices.

The proposed agreement between the utility and the Navajo Nation comes after years of intensive efforts by the grassroots community organizations Tó Nizhóní Ání and Diné CARE on the Navajo Nation and San Juan Citizens Alliance in the Four Corners area.

“The Four Corners region is being hit hard economically as coal goes away, and we deserve to be part of the economic diversification now recognized by APS and the Navajo Nation,” wrote Mike Eisenfeld, Energy and Climate Program manager for San Juan Citizens Alliance in Farmington, N.M., in a joint statement with Horseherder.

To secure support for communities, the groups submitted numerous comments, met with officials, and formally intervened in various regulatory proceedings, including the ones that led to the utility’s offer.

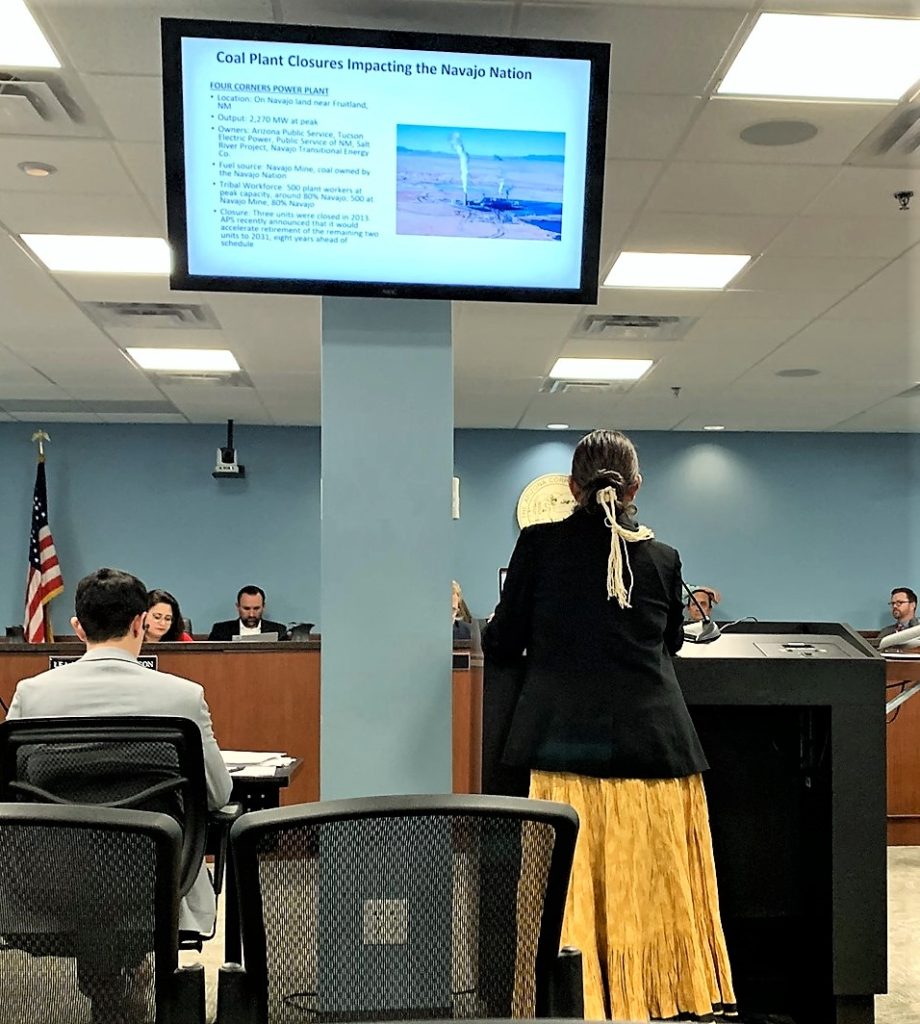

Tó Nizhóní Ání participant asks Arizona Corporation Commission for renewable energy development on lands of coal impacted tribal communities. COURTESY / Tó Nizhóní Ání

It corresponds to an amendment the grassroots groups proposed to state regulators, which was passed in September, requiring APS to create a Tribal Energy Efficiency Program. With it, ACS earmarked $457,000 annually for implementation of energy efficiency projects in Navajo and Hopi communities “impacted by the closure of coal-fired power plants that Arizona Public Service Company owns or operates.”

“Navajo coal and water and the workers from our communities provided the power that made the success of cities like Phoenix and companies like APS possible. Now that coal plants are no longer economic, it’s only right for some of that prosperity to come back to us,” said Robyn Jackson of Diné CARE in response to the utility giant’s announcement.

The consistent grassroots involvement helped spark the Navajo Nation to intervene in the APS rate case for the first time ever, with Navajo President Jonathan Nez offering testimony similar to that of the three community organizations earlier this year.

They recommended a number of just transition measures and payments of more than $200 million in financial support for the Navajo Nation and Four Corners area.

“We feel that sacrifices made by our people to provide Arizona cheap water and power deserve the full amount we requested in this proceeding, but this is nonetheless an important first step to establishing what corporate responsibility to communities looks like,” Horseherder said of the somewhat lesser amount offered.

Offer addresses history of grievances

The proposed agreement also provides compensation to the much smaller but no less stricken Hopi Tribe. It would mean $3.7 million for the tribe, which has suffered severe hardships as a result of the closure at this time last year of its Navajo Generating Station (NGS) and the Kayenta Mine that fed it.

Former Hopi Tribal Council Chair and now Black Mesa Trust Executive Director Vernon Masayesva explains that “the intent of coal mining on Black Mesa was: first, to provide low-cost electricity to bring water from the Colorado River to Phoenix and Tucson, via Central Arizona Project; second, to supply a huge demand for electricity in booming cities in the Southwest.

“Black Mesa became a sacrificial area for producing cheap electricity,” Masayesva wrote in a recent essay. The Hopi Tribal Council did not understand the magnitude of the mining and the devastation it would cause, he says.

“Little did they know that by the end of 2005, over 45 billion gallons of pristine groundwater would be used to operate a coal slurry project, enough water to sustain the entire Hopi population of 10,000 for over 300 years.

“Neither did they know that the hydrologic balance would be permanently and irreparably damaged. In fact, they claimed to have irrefutable proof that the negative impacts will be minimal,” he added.

“Agents of the federal government who approved the leases committing 670 million tons of coal on 68,000 acres to Peabody justified their decision by saying the economic benefits will far outweigh the damages,” he recalls.

“Today less than a dozen Hopis work at the mine; the Hopi Tribe is receiving less than $10 million, and unemployment is among the highest in Indian Country,” he observed 40 years after the onset of the project.

For nearly 50 years, Kayenta Mine served as the sole supplier of fuel for the Navajo Generating Station, or NGS, the largest coal-burning power plant in the West, co-owned by APS.

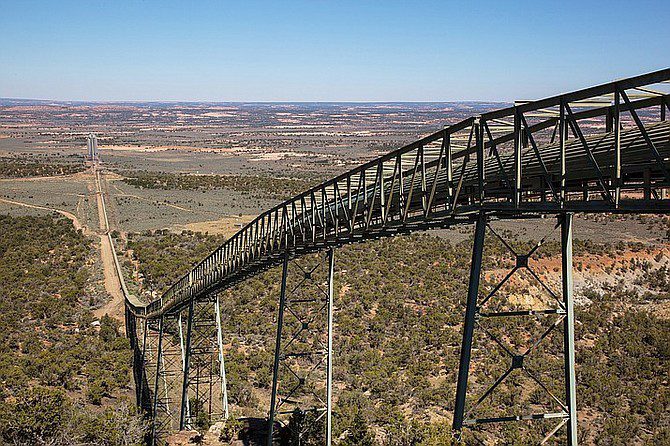

The mine, not far from Black Mesa, used drinking water to slurry around 8 million tons of coal annually to the plant located 90 miles away in federally recognized Navajo Nation jurisdiction near Page, Arizona, Glen Canyon Dam, and Lake Powell on the Colorado River north of the Grand Canyon.

In early 2017, as coal was becoming an increasingly uneconomic source of electricity, APS and co-owners of NGS decided to close the plant.

By 2018, when this picture was taken, the Navajo Generating Station was on its way to becoming a ghost of its former self. Photography by: Talli Nauman

Kayenta loaded its last trainload of coal to NGS in August 2019 and locked its doors for a good several months ahead of NGS’s retirement, according to a report released Oct. 29 by the Western Organization of Resource Councils (WORC).

In the year since Kayenta ceased operations, its co-owner Peabody Western Coal Co. has done “almost no reclamation work at the mine,” the report finds. Despite federal law requiring reclamation simultaneous to extraction, the coal pits have been left idle, with no significant backfilling or grading taking place, it says.

As of September, some 350 miners who worked at the mine were still out of jobs, with Peabody and the United Mine Workers of America unable to come to an agreement putting them back to work on reclamation activities, according to the 35-page report by public administration specialist and WORC regional organizer Kate French.

Besides holding a share of the Navajo Generating Station, APS is the majority owner and operator at Four Corners Power Plant on Navajo land in northwestern New Mexico, which is scheduled to close by 2031, and at Cholla Power Plant, which sits just south of the Navajo Nation and Hopi reservation in northeastern Arizona, and is scheduled to close in 2025.

Public sentiment favors reparations

Those plants have left significant contamination on Navajo land; they have used up enormous amounts of Navajo water, and pollution from their smokestacks has caused widespread health problems on the Navajo Nation, Tó Nizhóní Ání contends.

The other co-owners or principals in the three plants – Tucson Electric Power, Salt River Project, NV Energy, Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Central Arizona Project, Public Service of New Mexico (PNM) and the Warren Buffett-owned PacifiCorp – have contributed no transition support to date, despite one plant already being closed and the two others now having retirement dates set, the organization points out.

Statewide polling done in 2019 showed that 83 percent of Arizonans thought it was important “for the owners of the Navajo Generating Station to provide financial assistance and support such as job training for communities impacted by the closing of the plant,” with strong bipartisan support for the idea.

Over the past several years, other utilities in the West, like APS, have started to acknowledge that they simply cannot close down a power plant that has been operating for decades without providing transition assistance. They must instead provide financial and economic development support and commit to helping these communities rebuild, Tó Nizhóní Ání maintains.

A similar agreement was approved last year in New Mexico to provide transition support, economic redevelopment and worker transition related to the closure of the San Juan Generating Station, not far from the Four Corners Plant. There, the transition funding provided by PNM was made possible by a financial tool called securitization, which allows utilities to refinance undepreciated debt in uneconomic coal plants at much lower interest rates.

The savings help lower customer rates and at the same time free up capital earmarked for just transition support. Tó Nizhóni Ání, Diné CARE and San Juan Citizens Alliance are hopeful that a similar mechanism can be applied in Arizona.

New report recommends job replacement through reclamation

The WORC report, entitled “Coal Mine Cleanup Works,” concludes that thousands of jobs lost in the collapsing coal industry could be replaced through employment in removal of mine waste that is polluting tribal and other rural lands.

For starters, the Navajo Nation could benefit by 1,301 jobs and the Hopi Nation by 416, according to the 35-page report.

It shows that up to 200 Kayenta Mine employees could be back working full time on efforts to reclaim that land over the next few years, Horseherder said.

Kayenta Mine used underground drinking water to slurry coal to the Navajo Generating Station, both on Navajo territory, for electricity to support Phoenix and Tucson, Arizona. Credit Peabody Energy

“Navajo and Hopi workers who have been out of jobs for more than a year could be working to restore our lands and waters, but they’re not because since the mine closed last August, Peabody Energy is trying to push off its reclamation obligations for two to four more years,” she complained.

However, Peabody has submitted an application to the federal Office of Surface Mining, Reclamation and Enforcement to delay 70 percent of major reclamation for another two to four years.

“Peabody is just leaving big open pits sitting on our land, and people are still out of jobs at a time when we need it most,” Horseherder said.

Her organization seeks guidance from Indigenous wisdom to inspire all those who have the goal of economic diversification and local capacity building for “full ownership in sustainable energy projects.”

Participants of Tó Nizhóni Ání COURTESY Tó Nizhóni Ání

If the benefits participants pursue achieve a stamp of approval from regulators, Arizona Public Service Co. will provide a transition package that includes:

- Commitments to implement 600 megawatts of renewable energy projects on the Navajo Nation and in the Four Corners region, with 250 megawatts to come in the next two years.

- APS shareholder contributions of $2.5 million a year in revenue sharing with the Navajo Nation for APS’s transmission capacity on tribal land, beginning no later than 2031 and running through 2038, for a minimum of $17.5 million in payments, and perhaps as much as $30 million.

- Agreement to extend electric service free of charge to any Navajo households within 2,000-4,000 feet of an APS distribution line, depending on the results of a household census of Navajo homes lacking access to electricity that APS will conduct.

- $10 million for electrification of homes on the Navajo Nation not currently connected to the grid.

- $250,000 per year for five years dedicated to assisting the Navajo Nation with economic development efforts, with the time window to run from several years before to several years after final retirement dates for the plants still in operation.

- Assistance to the Navajo Nation in its efforts to acquire water rights associated with the Four Corners Power Plant.

- Additional financial support totaling $15.7 million for other coal-impacted communities, such as the Hopi.

“We are on the verge of transforming our economy from coal to clean energy, and commitments like this will be critical to shaping our future,” Diné CARE’s Jackson said.

This story was reported and produced with the generous support of the One Foundation.

Teaser photo credit: Nicole Horseherder. COURTESY/ Semester in the West