Today I’m going to begin my cycle of posts commenting on, expanding and perhaps occasionally qualifying the analyses in my book A Small Farm Future.

You have bought your copy by now, right? Ah well … far be it from me to tell you what to do with your hard-earned cash. Suffice to say that I’m not planning to summarise or repackage what’s in the book, so if you haven’t read it or aren’t an old hand on this blog, some of these posts may be a little mystifying in places. Others, though, should work as standalone pieces. One way or another, I hope you’ll find something of interest and perhaps some things worthy of debate within them.

I’m going to work my way through the book roughly in page order. The book starts with ‘The Civet’s Tale’, which I sketched in order to make the point that, almost invariably, the choices we make have downsides as well as upsides, perhaps in agriculture more than in most areas of life (and, unfortunately or otherwise, agriculture is at the root of all those other areas of life).

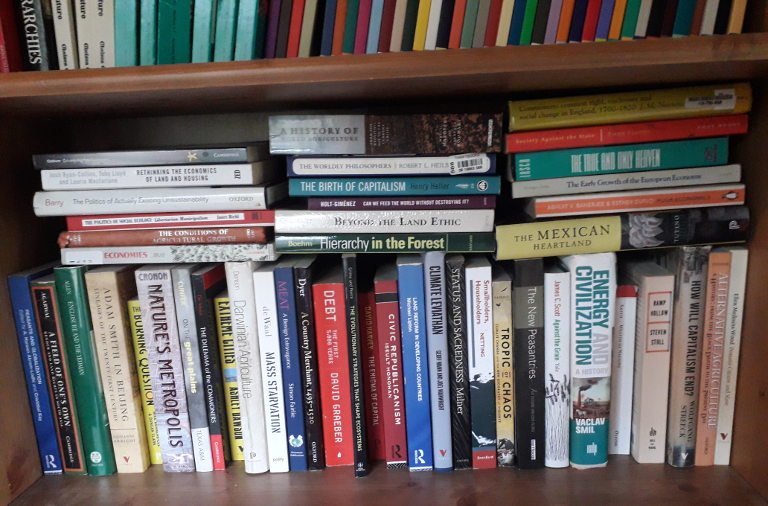

Another way of putting this, following on from my previous post, is that after only death and taxes (in fact, before taxes), a certainty in life is trade-offs. Arguing this puts me in the company of mainstream economists, whose discipline proceeds largely from the concept of opportunity cost or decision-making in circumstances of scarcity. There are those – often on the political left, my own political home turf – who insist that such notions are a conceit of our capitalist economic system, which manufactures an artificial scarcity. Along similar lines there are those in agriculture, both alternative and mainstream, who insist that there’s a ‘right’ way you can farm – out of which flows abundant produce, social harmony, a handsome income to the farmer and all other good and wholesome things1. Well … don’t get me wrong … honestly, I’m with the left, and I’m with the agrarian renegades. But on just a few significant points I’m also with the mainstream economists and the sceptics of cornucopia. As I see it, Harry Truman’s yearning for a one-handed economist is rightly destined to go forever unfulfilled. Perhaps this shelfie of some of the books that particularly influenced the approach I took in my own book illustrates the point – try to reconcile the arguments in all this lot.

On pages 1-3 of my book I try to thread a way through arguments from left and right, from ‘progressives’ and ‘conservatives’, about decision-making under circumstances of constraint – arguing that in the present world-historical moment this points to many more people than at present turning to an agrarian life. The rest of the book, and indeed this blog, is premised on working through those implications.

Although I share a trade-off based starting point with mainstream economic thinking, there are a couple of ways in which my analysis departs from it. One of them is that I’m open to the idea that ‘scarcity’ and ‘abundance’ are not analytical absolutes but in many ways are just words we attach to certain kinds of feelings (and there’s an underlying psychology to those feelings that I examine at various points in the book, particularly Chapter 16). The things humans need are both scarce and abundant, and the best place most of us can be for getting the measure of those twin truths is on the farm, where we have to build a livelihood in their shadow.

Another way I depart from mainstream economics is that, as I see it, only a few of these trade-offs are quantitative ones that can be expressed through the medium of money. Whereas it’s a commonplace of contemporary culture to say that arguments for a small farm life or for economic localism are romantic and fanciful, I argue in the book that the real romanticism in contemporary culture, the real fantasy, is our views of money, capital and trade as the solution to our problems, as the measure of our wellbeing and as a meaningful claim against the world. In this respect, anyone who says that my book is a nostalgic evocation of past rural worlds that are now inevitably lost to us either hasn’t read it or has badly misunderstood it.

But we’ll come back to money and markets presently. For now, I’ll conclude by highlighting a few of the trade-offs that I examine in the book, not many of which are ‘economic’ ones in the usual sense of the term.

So as I see it (and as I explain in more detail in my book), you can’t usually or easily:

- Produce more food or fibre from a given area without creating more work for somebody, or more pollution, or more stress on wild organisms, or all of those things.

- Introduce ‘improvements’ into a society that aren’t experienced as degradations for some people – thereby calling into question singular narratives of universal social ‘progress’

- Develop new crop varieties that involve significantly less labour input and less environmental impact, but yield as well or better than older varieties

- Create globalized networks of profit-seeking trade without degrading human and non-human ecologies somewhere

- Create collective forms of human organisation without creating interpersonal conflicts

- Dismantle collective forms of human organisation without creating other interpersonal conflicts

- Build and populate cities without energetic and social costs

- Surrender a sense of personal autonomy without spiritual cost

Some of these issues we’ve already discussed at length and picked over on this blog, but in the posts to come I’ll try to lay them out (alongside other issues) afresh once more to fill in some of the gaps in the book and round out its analyses. I hope you’ll join me.