One of the pleasant side effects of the series of vignettes about America’s magical history I’ve been posting here of late has been the chance to look into some of the odder aspects of this nation’s trajectory through time. The magical heritage of the United States has spread into some very strange corners of our culture and history, and chasing those down has very often been entertaining. That’s what I was doing a week ago, following the track of Theosophy through the colorful realm of 1930s pulp literature, when three pieces of a puzzle I hadn’t known I was working on suddenly clicked together.

As it happens, the puzzle had only a peripheral connection with pulp literature, and not much more of a connection with Theosophy. Nor does it have to do with the magical history of America in any straightforward sense. It centers on a challenging constellation of ideas we’ve already discussed more than once in these notional pages, and the collective response (or nonresponse) to those ideas. What made the pieces of the puzzle click together for me was a single very short phrase. We’re about to do an old-fashioned word association test, dear reader, to see if the phrase has any of the same resonances for you that it did for me. Your task is to see what you think of first when you encounter the phrase. Ready?

The phrase is “the Shadow.”

Did that make you think of:

a) The famous 1930s pulp magazine and radio drama figure with the sinister laugh?

b) The Dark Lord Sauron, the antagonist in J.R.R. Tolkien’s trilogy The Lord of the Rings?

c) The archetype delineated by Carl Jung in his writings on analytic psychology?

It made me think of all three—and thereby hangs a tale.

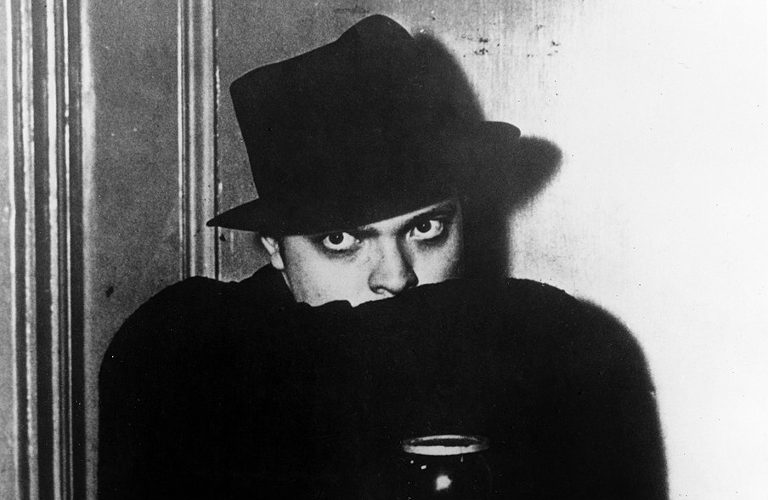

Let’s start by filling in a few of the blanks for those of my readers who haven’t encountered these Shadows in their natural habitats. The first Shadow sprang into being unexpectedly in 1930, when Street & Smith, the great pulp-magazine publishing firm, decided to try to boost sales of their popular weekly pulp Detective Story by sponsoring a radio show, “Detective Story Hour,” which dramatized one story from each issue. This was the era of live radio, and performers were expected to ham it up a bit on the air. The narrator of the show thus started calling himself “the Shadow” and leading off with what became a legendary tag line: “Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows…” followed by a laugh soaked in the triple-distilled, charcoal-filtered essence of human wickedness.

Readers immediately began deluging Street & Smith with questions about the mysterious Shadow. Bill Ralston, the firm’s general manager, scented a cash cow, and tapped prolific pulp writer and journalist Walter B. Gibson to bring the Shadow to life in magazine form. A quarterly, The Shadow Magazine, duly appeared. By the end of the first year it was raking in cash at such a rate that Street & Smith changed its schedule to twice a month, where it stayed until wartime paper restrictions slowed things down in 1943. A radio show, a comic book series, a newspaper comic strip, and a flurry of Saturday afternoon movie serials (the precursor of the Saturday morning kiddie shows on television) duly followed.

Great literature? Not a chance. Great fun? Now you’re talking. The Shadow was one of the first imaginary crimefighting heroes with a secret identity. (That identity varied depending on whether you read the pulps or listened to the radio drama: it was Kent Allard in the former and Lamont Cranston in the latter.) He wore a hat pulled down low, a red scarf covering the lower half of his face, and a great swirling black cape; he had a great beak of a nose, and blazing eyes; he had the power to cloud men’s minds, which he’d learned from yogis in India; and he also packed a pair of automatic pistols in case some less mystical option was called for. He lurked in the darkness or paraded around in a galaxy of impenetrable disguises, hunting down a giddy assortment of psychopathic master criminals. What evil lurked in the hearts of men? The Shadow had it down cold.

So that’s Shadow #1. Shadow #2, the Dark Lord Sauron, had his genesis in the same decade as Walter Gibson’s creation. J.R.R. Tolkien, an Oxford professor who told elaborate stories to his own children, began writing one of those down around 1930, and it was published as The Hobbit in 1937. Well stocked with wizards, dwarves, trolls, goblins, hostile elves, and one of the finest dragons in literature, it became an immediate bestseller. Within months of its appearance, buoyed by the enthusiasm of his young readers, Tolkien began working on a sequel, which he intended to be another children’s story. It didn’t stay that way for long. Terrifying Black Riders showed up nearly at once—Tolkien noted later that he was just as surprised by their sudden appearance as his protagonists were—and something else began to loom up behind them, a vast presence blotting out the stars.

“The new Hobbit,” as Tolkien started out calling the sequel, ended up being named after that vast presence: the only Lord of the Rings in the trilogy, of course, is Sauron the Dark Lord, master of the Black Riders and most (though not all) of the evil entities in Tolkien’s sprawling imaginary cosmos. The reader never sees Sauron; Tolkien, a skilled watercolorist, painted him once but had the good literary sense to realize that Sauron was more effective as an absence than he could ever have been as a presence. Even at his closest, he is always just past the edge of the reader’s vision, and he spends most of the trilogy as a looming darkness far away.

From the early drafts of the manuscript, accordingly, Sauron, his servants, and everything else related to him came to be summed up by the phrase we’re discussing: “the Shadow.” The Shadow is a pervasive presence all through the story, and the entire action of the plot is based on the idea that if the right person can do the right thing at the right moment, the Shadow will pop like a bubble and go away once and for all. That won’t leave the world perfect—Tolkien was a much better writer and a much more conservative Christian than that—but the terrible threat against which the protagonists must fight will dissolve like mist before the wind.

It was an elegant literary construction, a way of highlighting the moral challenges and choices faced by Tolkien’s other characters by placing them in front of a backdrop made of pure darkness. It became something far more significant, and far more troubling, when Tolkien’s trilogy became a cult classic among the young and hip in the 1960s. We talked two weeks ago about another set of cult classics in that era, the novels of Hermann Hesse; Tolkien appealed to much the same market that Hesse did, but his work suffered a different fate. The severe and serious conservatism that pervades the trilogy—Tolkien was politically on the extreme right, a detail most of his fans have been at great pains to obscure—was first ignored and then erased, with the help of bad movies and an entire industry of shoddy Tolkienesque knockoff novels that plagiarized all his imagery and evaded all the ideas that gave them meaning. The consequences—well, we’ll get to those in a bit.

First we need to encounter Shadow #3, the one that Swiss psychologist Carl Jung anatomized in so troubling a fashion. Jung, as I hope most of my readers are aware, started out as a disciple of Sigmund Freud but broke with him in 1913 over basic disagreements over the nature and meaning of the unconscious mind. To sum those up very briefly, Freud insisted that the unconscious was simply the instinctual, animal mind—the id, in Freudian terms—which was mostly interested in sex, and had to be disciplined and controlled by the ego in obedience to the conscience, the voice of the superego.

Jung found in his own work with himself and his patients that the unconscious mind could not be summed up so simply, and at first saw the unconscious as containing two layers. One of them consisted of those things the ego didn’t want to recognize in itself, and so was entirely personal in nature: the personal unconscious, as Jung called it. The second layer consisted of contents that were not personal, had never been conscious in the first place, and formed the deep structure of the human psyche. This layer he termed the collective unconscious.

Until the start of the 1930s—that decade again—that was Jung’s basic theory. What happened then was that he traced the roots of the conscious self and the personal unconscious right down into the collective unconscious. The basic structures of the collective unconscious, he came to see, were the archetypes: a set of roles or functions that were hardwired into the human mind at a deep level, and served as expressions in consciousness of the basic biological instincts we inherit from our animal ancestors. Once you reach a certain stage of sexual maturity, for example, your mind is hardwired to look for a lover: that’s one of the most obvious archetypes, the one Jung called the anima or animus (depending on your gender and sexual orientation).

For all practical purposes, once it’s triggered by some complex set of psychological stimuli, the anima or animus functions as a prolonged case of beer goggles, projecting itself onto the other person and making them look just like the woman or man of your dreams, no matter how faint the resemblance might be in the eyes of your friends. That’s how all archetypes work: they scoop up the relevant contents of your mind, constellate them (that is, fit them into the archetypal pattern), and project that onto the nearest available target. What Jung came to realize as he pursued his investigations into archetypes is that what he’d been calling the conscious self and the personal unconscious were also archetypes. Who you think you are is a construct made up of all the things you think you ought to be, constellated around the archetype Jung called the ego.

Then there’s all the things you think you shouldn’t be, the contents of the psyche that Freud identified with the whole unconscious mind, which constellate around an archetype of their own. In Freud’s own Victorian setting, among the neurotic middle class women who provided him with most of his patients, most of those contents did in fact have to do with sex, but that was an artifact of his own era and culture. In a society with different hangups, different contents fill the blank slate of the archetype—but those contents always come from within the individual. That’s why Jung, in a series of pathbreaking essays written in 1934 and 1938-9, came to call the archetype in question the Shadow.

The Shadow is everything about yourself you hate so much that you’re not willing to admit that it’s part of yourself. Thus, just as inevitably as your anima or animus projects itself on your actual or potential lovers, your Shadow projects itself on your enemies. Still, there’s a difference between the Shadow and the other archetypes. The contents that fill the other archetypes mostly come from other people: every mentor you’ve ever had helps provide raw material for the archetypes of the Wise Old Man and Wise Old Woman, for example, the archetypes that exist for the purpose of getting you to listen and learn from elders, just as whatever aroused your sexual desires most strongly in adolescence provided raw material for your anima or animus.

The Shadow, by contrast, is utterly personal. The contents that it constellates all come from yourself, and there’s good reason for that. Like all the archetypes, the Shadow is the expression of a basic animal instinct. It evolved to whip you into a blind homicidal rage when you have to face an enemy, so that you set aside ordinary human concerns and rip the other person to bloody gobbets. Natural selection being the harsh taskmaster that it is, the aggressive instinct homed in on the things that would produce blind homicidal rage most effectively. Yes, those would most reliably be the things you can’t stand about yourself.

It’s a fascinating synchronicity, to borrow another of Jung’s concepts, that these three Shadows all constellated themselves in the creative imagination of the Western world in the same decade. The 1930s were a good decade for such exercises. As it began, the golden afternoon of delusion that was the 1920s, when people of good will convinced themselves that the War to End Wars really had done the job and an immense economic boom seemed to promise good times forever for everyone who mattered, still hovered close, and the US stock market crash of October 1929 hadn’t yet triggered more than an ordinary recession—the missteps that turned it into the Great Depression were just then being made. Thereafter, year by year and very nearly day by day, everything went wrong, until September 1939 arrived and the world blew itself apart.

What’s more, behind all of it was the Shadow in Jung’s sense, and also in Tolkien’s sense. In Germany, over the course of that decade, one of Europe’s great nations discarded its own grand heritage of humanism and philosophical thought in what amounted to a nationwide psychotic break. There was plenty of history behind that, to be sure. From 1871 on, a great many Germans built their collective ego around the notion that Germany was destined to be a global imperial power. The unwelcome reality was that theirs was a small nation with few natural resources and no defensible borders, hopelessly outmatched in an age of continental powers with vast oilfields.

In 1917 they got slammed face first into that reality when the United States came into the First World War, propped up the French and British armies when those were on the brink of collapse, then flooded the Western Front with a torrent of munitions, supplies, and fuel, and the first wave of an almost unlimited supply of manpower. A year later the war was over and Germany had lost—but that was not something most Germans could accept. Instead, they went looking for scapegoats within Germany who could be blamed for the defeat of their invincible nation, and an unpleasant little man with a toothbrush mustache was happy to provide them with one.

In France and Britain, in turn, a great many people built their collective ego around the notion that their nations were innocent of any wrongdoing while Germany and its allies had started the First World War out of pure unmitigated evil. The unwelcome reality was that France and Britain were brutal imperial powers which treated their colonies around the world the same way the Germans were accused of treating Belgium and France, and which had contributed mightily to the cascade of blunders that caused the First World War. Obsessed with the desire to blame Germany for the war, the French and British goverments demanded terms at the peace treaty negotiations so harsh that they left Germany economically and politically crippled. That made it easy for the unpleasant little man just mentioned to turn a fringe party into one of the twentieth century’s most terrifyingly effective political machines and ride it straight into power.

As the 1930s lurched toward their catastrophic end, in other words, millions of Germans blamed the Jews for Germany’s failures, millions of French and British people blamed the Germans for their own countries’ failures, and both sides proceeded to make a set of moronic blunders indistinguishable from those of 1914 except in detail. The result was the bloodiest war in recorded history, and the transformation of Europe from the imperial center of the planet to a half-ruined wasteland split down the middle and shared out between the United States and the Soviet Union. If this suggests that projecting the Shadow makes for incompetent politics and disastrous outcomes, why, yes, that’s what it suggests to me, too.

Thus the 1930s were a good time to think about the riddle of evil. Two of the Shadows we’ve been discussing represent diametrically opposed answers to that riddle. Tolkien’s answer, an answer he meant as a literary device but became much more than that once his trilogy became part of the mental furnishings of an entire generation, was to see evil as something outside the self, a vast and all-pervading Enemy whose only purpose is to oppose everything that the protagonists think of as good and right and true. Jung’s answer, an answer he didn’t intend as a literary device but became one in the hands of his good friend Hermann Hesse, was to recognize that the Shadow we hate and fear is always cast by the qualities in ourselves that we can’t stand and won’t admit we have.

Both approaches have their political dimension. We’ve discussed that dimension of Tolkien’s Shadow above, and seen its results. The political dimension of Jung’s Shadow was set out crisply by Hermann Hesse in his essay “O Friends, Not These Tones,” written at the beginning of the First World War, which tried to convince other German authors not to join in the demonization of France and England that pervaded Germany just then (and was mirrored precisely by the demonization of Germany that pervaded France and England at the same time). It wasn’t a pacifist tract—that’s the most significant thing about it. Hesse was ready to support his country in war, and went on to do so. He simply argued that whipping up blind rage toward the enemy wasn’t useful. He spoke for a calm, reasoned, effective foreign policy in war as well as peace.

Of course he was shouted down in vicious terms. Thomas Mann, later one of Hesse’s closest friends, disgraced himself with a tirade condemning Hesse as little better than a traitor, and his was far from the worst response Hesse got. Hesse was right, and history shows with agonizing clarity just how right he was, but no one cared about that at the time.

All that was long ago, of course. Two weeks ago, however, we talked about the novels of Hermann Hesse: how they and Tolkien’s great trilogy became the cynosures of a generation of youth, and how Hesse then got dropped like a hot rock while Tolkien, or at least a stuffed and mounted facsimile thereof, stayed fashionable. At the heart of that difference, I’m convinced, is the radical difference in the Shadows the two authors portrayed. In Hesse’s novels, when you have two characters that are moral opposites, they contend with one another until something new is born. In Tolkien, when you have two characters that are moral opposites, one of them must die. We know which of those became the common currency of popular thought in our time.

So if you’re wondering, dear reader, why those of us in the USA live in a country where one party accuses the other of being full-blown goose-stepping Nazis and the other party insists that the first are Satan-worshiping pedophiles, where compromise has become a swear word and both sides have convinced themselves that all they have to do is come up with the right gimmick and the Shadow they hate so much will pop like a bubble, now you know. The bitter irony, of course, is that they’re both wrong. No matter how many self-proclaimed Frodos drop surrogate Rings into notional equivalents of Mount Doom, the Shadow will not go away, because it’s being projected by the people on both sides who have convinced themselves that they’re fighting it.

If there’s a solution—other than mutual slaughter, that is—maybe it’s to be found in the first Shadow we discussed, the one who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men. (Not, please note, their minds—it’s in the heart, the seat of unbalanced passion and distorted love, where the evil that matters has its root.) That tremendous, mordant, terrifying laugh is only possible for one who has already confronted the unbalanced passion and distorted love in his own heart. If there’s a way forward for us here in the United States, that knowledge might just provide it.

*********

This is my last substantive post before the US presidential election on November 3. I’ll have an open post on the 28th, and my regular post on the 4th will be written over the week preceding the election. If you come here on the morning of the 4th expecting to see a review of the carnage, in other words, you’ll be disappointed—but then, astonishing as it may seem to those who have allowed politics to devour their lives, there are things other than presidential elections worth discussing! See you then.

Teaser photo credit: By Mutual Broadcasting System (Corporate Author) – PBS, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9558346