Ed. note: Robert Jensen, “Who is we?” The Ecological Citizen, 4:1 (2020): 57-61. (The version below is slightly revised for a forthcoming book, The Perennial Turn, edited by Bill Vitek.)

Who is “we”?

We humans have made a mess of things, which is readily evident if we face the avalanche of studies and statistics describing the contemporary ecological crises we face. But even with the mounting evidence of the consequences for people and planet, we have not committed to a serious project to slow the damage that we do.

One reasonable response to those statements is, “Who is ‘we’?” That is, exactly who has made a mess of things and who has failed to take action? Who’s to blame for the problems and who’s responsible for the costs? Put more bluntly, borrowing from the often-quoted exchange between the Lone Ranger and Tonto, “What do you mean, we, white man?”

The global North—which is to say, fossil-fuel powered capitalism as it developed in Europe—bears primary responsibility for the contemporary crises, and those societies have failed to meet their obligations, or in some cases to even acknowledge obligations, to change course. And within those societies, it is the wealthy and powerful who bear the greatest responsibility for destructive policies.

Today, “we” is not everyone, equally culpable. But if there is to be a decent human future—indeed, if there is to be any human future—we have to realize that human-carbon nature is at the core of the problem, a reality that exempts no one.

Because this sounds harsh in a world with so much human suffering, so unequally distributed, let me be clear: My argument does not minimize or trivialize that suffering, or ignore the profound moral and political failures that exacerbate it. Strategies for a sustainable human presence must involve holding the wealthy and powerful accountable for damage done, and moving toward a more equitable distribution of wealth and power—goals that are desirable independent of ecological realities. But if that realignment were accomplished, then what? With nearly eight billion people and most of the world’s infrastructure built with, and dependent on, highly dense energy, then what?

It’s tempting to believe that we can identify low-energy societies from the past, or communities in the contemporary world with lower-energy living arrangements, and reproduce them more widely. It’s tempting to believe that breaking concentrated wealth and power and expanding democratic decision-making would lead to sustainable societies. But such hopes are based on a misunderstanding of the problem.

We should learn from the low-energy societies and experiments within today’s societies, but those good examples don’t offer a program for moving from the current state of most of the planet (high-energy, unsustainable) to where we need to be (low-energy, sustainable). Because no one can imagine what such a program would look like, people are quick to embrace a “technological fundamentalism” that pretends we can continue at high-energy levels through some magical combination of innovation and renewable energy, which are important but cannot keep the contemporary world afloat.

We can’t pretend that people, if freed from hierarchal social systems, will suddenly find it easy to avoid the comforts and pleasures associated with dense energy, to which people have become accustomed (in the more affluent societies) or to which others aspire (most everywhere else). While much irrational consumption is driven by capitalist propaganda (that is, advertising and marketing), fossil fuels and other sources of energy also make people’s lives easier in many ways that are not frivolous. There is variation in people’s assessment of their needs, but capturing and using dense energy for comfort and pleasure is not a unique goal of imperialists and capitalists.

In short, there are no solutions, if by solutions we mean ways to support anything like the existing number of people at anything like the existing level of aggregate consumption. Wishing it to be possible, simply because the alternatives are difficult to imagine—let alone achieve—does not make it possible.

Again, for emphasis

So as not to be misunderstood: We live amid dramatically different levels of energy consumption, resource exploitation, waste production, and overall contribution to ecosystem instability. This highly skewed distribution of wealth is a product of crimes of the past (especially, but not limited to, the barbarism of European nations in their world conquest over the past 500 years) and ongoing economic domination (when imperial armies go home, private firms continue to exploit resources and labor, typically with local elites as collaborators).

The profoundly unsustainable nature of human economic activity today is the result primarily of a rapacious transnational corporate capitalism. Because capitalism is, and always has been, a wealth-concentrating system, a relatively small number of people reap most of the financial benefits from this ecological destruction. In short: The First World is rich, and much of the wealth of the First World is concentrated in the hands of a relatively small segment of those societies’ populations.

Some people who benefit from these arrangements are dedicated to maintaining the hierarchical systems at the heart of the unsustainable economy and its unjust distribution of wealth. Other people who benefit will condemn those systems but take no action to disrupt them. And some people will work for change. We all should do a self-inventory, uncomfortable though it may be, to assess honestly where we fit in these categories.

I am white, male, born and raised in the United States, educated, retired from a professional job—all realities that have enhanced my opportunities and reduced impediments. While I have been an active member of various movements for sustainability and justice, I will never have a satisfactory answer to a troubling challenge: “Why have you not done more?” And while I am reasonably frugal and consume less than most people of my class in the United States, I have no illusions that I live at a sustainable level.

To repeat, one more time: We are not all similarly situated, and this inequality within the human family must never drop out of our analysis. But when analyzing the ecological crises facing humans today, I believe it is important to talk about a “we” that includes everyone—on biological, historical, philosophical, and political grounds.

We are one species

First, it should be uncontroversial to assert an anti-racist principle anchored in basic biology: We are one species, and while there are observable differences in such things as skin color and hair texture, there are no known biologically based differences in intellectual, psychological, or moral attributes between human populations from different regions of the world. There is individual variation within any human population in a particular place (obviously, individuals in any society differ in a variety of traits) but no meaningful differences between populations in the way people think, feel, or make decisions. Again, we are one species. We are all basically the same animal.

Second, although we are one species, there are obvious cultural differences among human populations around the world. If those differences aren’t a product of human biology—that is, if they aren’t the product of any one group being significantly different genetically from another, especially in ways that could be labeled cognitively superior or inferior—then development of different cultures in different places must be the result of humans living under different material conditions. The type of living arrangements that groups of humans develop arise out of the differences in geography, climate, and environmental conditions. The different material realities under which humans have lived shape the different forms of human culture.

Third, we know that we make decisions, individually and collectively, in ways we do not and cannot fully understand. Our experience of freely choosing does not mean that all of our choices are 100% freely made. Without attempting to resolve the age-old debate on free will, we can self-reflect on how we often come to recognize that our choices, which we believed that we made freely at one moment in time, were shaped and constrained by material conditions we could not understand at that moment, and maybe never fully understand. While we continue to act day-to-day on the assumption of free will, we also should continue to be alert for ways behavior is to some degree determined.

Finally, the implications of all this: We should condemn the unsustainable and unjust actions of others and be critically self-reflective about our own contributions to unsustainable and unjust systems. We also should extend such critique not only to individuals but to the systems that reward pathological behavior and impede virtuous behavior. But thinking historically, we also should recognize that any group of humans living under the same material conditions would most likely have developed in roughly the same way.

That is, there’s nothing particularly special about any one of us or any one group of people.

This caution is a way of extending “there but for the grace of God go I” beyond the individual to cultures. That phrase emerged from Christian testimony to God’s mercy, but I use it here in secular fashion: If one has lived an exemplary life, that’s great, but be aware that life might have been very different if some of the material conditions in which one lived were different. To those who believe they have accomplished something and made a positive contribution to the world, that’s great, but a reminder: Change up any one of the conditions in our lives, especially in our formative years, and perhaps we would have found ourselves failing instead of succeeding. That doesn’t imply that we have no control over our lives, but simply that we likely don’t have as much control as we tend to assume.

This is true of us individually and collectively. The conditions under which a culture emerged may have led to ecologically sustainable living arrangements, but those arrangements might have been very different if initial conditions had been different. If Culture A created an ecologically sustainable way to live and Culture B created an unsustainable system, it is important to highlight the differences, endorse Culture A, and try to change Culture B. But if the geography, climate, and environmental conditions out of which the two cultures emerged had been different, then what would A and B look like? There but for the grace of God go we.

For example, not all cultures developed the technology to plow the ground, smelt ores, or exploit fossil fuels to do work in machines. The cultures without those technologies have not depleted the carbon in soils, forests, coal, oil, and natural gas at the same rate as societies with those technologies. If the development of those technologies was not the product of inherently superior intelligence—remember, we are committed to an anti-racist principle that flows from basic biology—the forces that led to the creation of such technologies must have been a result of the specific environmental conditions under which that culture evolved. Likewise, the lower rate of carbon depletion that results from the absence of those technologies cannot be a marker of inherently superior intelligence, but rather a product of environmental conditions. In a significant sense, the trajectory of people and their cultures is the product of which continent and in which region they have lived (Crosby, 2004; Diamond, 1997; Morris, 2010).

Humility all around

Recognizing that material realities shape our lives does not absolve anyone or any society today of moral accountability for actions, or lack of action. For those of us holding a disproportionate share of the world’s wealth who are responsible for a disproportionate share of ecological destruction, an awareness of some level of environmental determinism is not a free pass. Whatever people knew about ecological consequences when today’s cultures first developed, we now know more than enough to act on what our own moral principles demand of us—pursuing living arrangements consistent with ecological sustainability and social justice. If we fail to live up to those principles, we are appropriately the targets of demands for corrective action.

But in trying collectively to find a way out of the mess we’ve made, the assigning of different levels of responsibility for the mess is only a first step. No culture has a plan for transitioning from an unsustainable high-energy, interdependent global society of eight billion people to sustainable low-energy societies with smaller populations. While lessons from low-energy societies will undoubtedly be valuable, there is no way to flip a switch and return to a previous era’s living arrangements. Technological innovation and renewable energy will play a role but cannot replace the infrastructure of a world built with highly dense carbon. Breaking the grip of concentrated wealth on politics won’t change the fact that dense energy makes our lives easier in many ways that most people enjoy and will not want to give up.

Said differently: Human nature is relevant.

People advocating for social justice and ecological sustainability typically are nervous around talk of human nature, given capitalists’ success in defining our nature as inherently greedy and self-interested. Humans have the capacity to act in greedy and self-interested fashion, of course, but capitalism’s critics point out that we also have the capacity to collaborate and cooperate, which is also part of our nature—a crucial part in the story of human expansion across the globe (Despain, 2010).

My concern is with another aspect of human nature, what we might call our human-carbon nature, a phrase that reminds us that we are carbon-based like all other life on Earth. What is life? What is the nature of living things? Wes Jackson suggests that one answer is, “Life is the scramble for energy-rich carbon” (Jensen, 2021). It is our human nature, like the nature of all life, to seek out energy-rich carbon. Over time, humans have gotten exceedingly good at it, maximizing the extraction of all the carbon we can get our hands on. Exceptions to that pattern are rare.

Coping with the consequences of that carbon-seeking—an aspect of our human-carbon nature—is now our daunting challenge. Our greatest success as a species has become our most profound failure. This is a new challenge for which we have no road map. No existing ideology or culture is going to provide us with a template for dealing with what lies ahead.

It is too glib to say it’s ironic that some of the places in the world that contributed the least to climate change are going to suffer the most from climate disruption. It is too glib to observe that the world is not fair. Ecological realities challenge our policy-making capacities and threaten to overwhelm our moral imaginations. But we can agree not to hide from such realities and press forward.

Renouncing First-World dominance is a start, as is imagining a world beyond capitalism’s obsession with growth and consumption. The end of those systems is a necessary but not sufficient condition for change. If we start with an awareness of the scope of the change needed and the lack of a plan, we can at least be clear about the direction in which we need to move. And that requires committing to being the first species that will have to impose limits on itself, which means a cap on the carbon we use and rationing to ensure fairness (Cox, 2020).

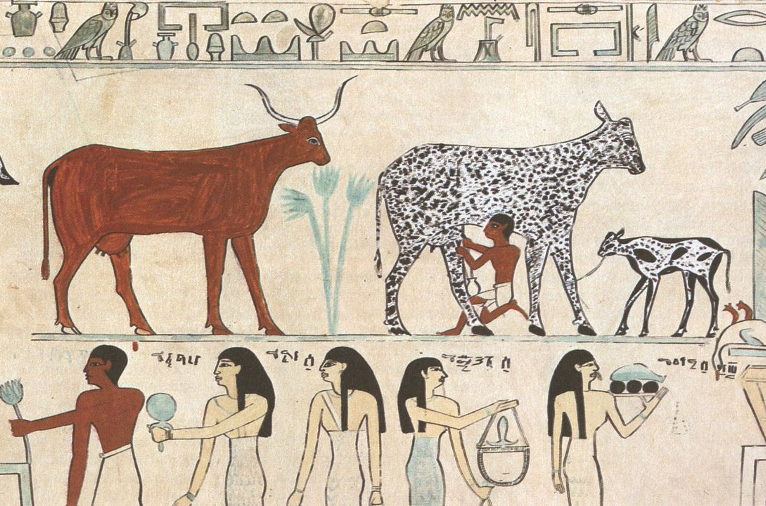

Our chances are better if we take the long view and realize that the problems we face aren’t just the consequence of the past 250 years of fossil-fuel use or the past 500 years of European colonialism. We have to go back further, to the origins of agriculture 10,000 years ago, the crucial fault line in human history, when humans began exploiting carbon at levels beyond replacement levels (Montgomery, 2012), particularly where grains (e.g., wheat and rice) were farmed by annual plowing that disrupted and degraded the soil.

Agriculture did not develop in the same way everywhere on the planet; geography, climate, and environmental conditions set the parameters within which people farmed. Especially where grain crops dominated, the ability to create and store surpluses generated the hierarchies that have produced profound social inequality (Scott, 2017). Surplus-and-hierarchy predate agriculture in a few resource-rich places (Pringle, 2014), but the domestication of plants and animals spread that dynamic across the globe, and agriculture was the beginning of the idea that we humans, rather than the ecospheric forces, control the world.

The “we” is us, Homo sapiens, the primate with the big brain. The first farmers, the first smelters of ore, the first people who tapped fossil fuels to do work in machines—all of them contributed to the mess we are in, but without knowledge of the consequences of their actions. We can say of those early carbon-seekers, “Forgive them, for they know not what they did” (Luke 23:34).

Today, we know what we do. The question is, can we—all of us—face what lies ahead without diversion and without illusion?

References

Cox, S. (2020). The Green New Deal and beyond: Ending the climate emergency while we still can. City Lights.

Crosby, A. W. (2004) Ecological imperialism: The biological expansion of Europe, 900-1900 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Despain, D. (2010, February 27). Early humans used brain power, innovation and teamwork to dominate the planet. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/humans-brain-power-origins/

Diamond, J. (1997) Guns, germs, and steel: The fates of human societies. W.W. Norton.

Jensen, R. (2021) Prairie prophecy: The restless and relentless mind of Wes Jackson. University Press of Kansas.

Montgomery, D. (2012). Dirt: The erosion of civilizations (2nd ed.). University of California Press.

Morris, I. (2010). Why the West rules—for now: The patterns of history, and what they reveal about the future. Picador/Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Pringle, H. (2014, May 23). The ancient roots of the 1%. Science, 344(6186), 822-825. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.344.6186.822

Scott, J. C. (2017). Against the grain: A deep history of the earliest states. Yale University Press.

Teaser photo credit: By Unknown author – Scanned from 1000 Fragen an die Natur, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1948., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2959985