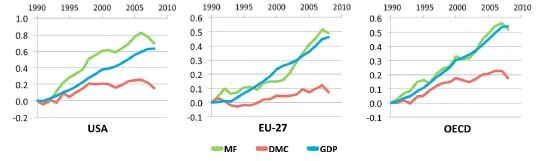

A number of people have asked me to respond to a piece that Andrew McAfee wrote for Wired, promoting his book, which claims that rich countries – and specifically the United States – have accomplished the miracle of “green growth” and “dematerialization”, absolutely decoupling GDP from resource use. I had critiqued the book’s central claims here and here, pointing out that the data he relies on is not in fact suitable for the purposes to which he puts it.

In short, McAfee uses data on domestic material consumption (DMC), which tallies up the resources that a nation extracts and consumes each year. But this metric ignores a crucial piece of the puzzle. While it includes the imported goods a country consumes, it does not include the resources involved in extracting, producing, and transporting those goods. Because the United States and other rich countries have come to rely so heavily on production that happens in other countries, that side of resource use has been conveniently shifted off their books.

In other words, what looks like “green growth” is really just an artifact of globalization. Given how much the U.S. economy relies on globalization, McAfee’s data cannot be legitimately compared to U.S. GDP, and cannot be used to make claims about dematerialization. If McAfee wants to compare GDP to domestic resource consumption, then he needs to first subtract the share of US GDP that is derived from production that happens elsewhere. He does not. Nor is this possible to do.

Ecological economists have been aware of this problem for a long time. To correct for it, they use a more holistic metric called “raw material consumption,” or Material Footprint, which fully accounts for materials embodied in trade. When we look at this data, the story changes. We see that resource use in the United States hasn’t been falling at all; in fact, it has been rising along with GDP. The same is true of all other major industrial economies. There has been zero dematerialization. No green growth. And indeed when it comes to excess resource use, rich countries are the biggest problem – not the saviours that McAfee suggests they are.

In this new piece, McAfee attempts to defend himself with a series of claims that raise interesting questions. I will respond briefly here:

1. First, McAfee points to the fact that rich nations have reduced their air pollution. This is proof, he says, of the Environmental Kuznets Curve, where impacts rise with GDP up to a point, and then begin to decline as GDP continues to go up. McAfee says “The EKC is a direct refutation of a core idea of degrowth: that environmental harms must always rise as populations and economies do. It’s not surprising that today’s degrowth advocates rarely discuss the large reductions in air and water pollution that have accompanied higher prosperity in so many places around the world.”

In reality, degrowth scholarship is full of references to the EKC; it is widely acknowledged. McAfee would know this if he engaged with the degrowth literature. We note, however, that the EKC is known to apply to only a limited range of impacts (such as air pollution). It does not apply to impacts like resource use and energy use, which rise inexorably along with economic growth (and which are, for this reason, the focus of degrowth analysis). The spottiness of the EKC is well established in the empirical literature (see, for instance, Stern’s recent review, “The Environmental Kuznets Curve After 25 Years”). McAfee ignores this fact in order to create the impression (as in the quote above) that the EKC applies universally to all environmental harms. There is nothing to be gained by papering over the nuance in the EKC literature.

Moreover, even where the EKC does apply, the literature is increasingly clear that it’s not income growth itself that drives the reduction in pollution (as McAfee implies when he says “prosperity bends the curve”); rather, it is policy interventions, and specifically legal limits. London’s mayor Sadiq Khan has massively reduced the city’s air pollution over the past couple of years. Is this because London’s GDP has suddenly increased? No, it’s because Khan, unlike his predecessor, has introduced laws to reduce air pollution. This could have been done decades earlier with the same effect, regardless of how much GDP the city might have had at any given time.

Indeed, Stern’s conclusions about the relationship between GDP and pollution are worth noting: “The effect of economic growth on pollution is generally positive… The evidence shows that over recent decades economic growth has increased both pollution emissions and concentrations, ceteris paribus [i.e., when controlling for all other factors]… This reinforces the early concerns that the EKC literature might encourage policy-makers to incorrectly de-emphasize environmental policy and pursue growth as a solution instead.” And that’s exactly the error that McAfee has committed.

So, yes, air pollution can be decoupled from GDP, with policy. We have known this for a long time. But that has nothing to do with the question of dematerialization, which is the focus of McAfee’s book, and which is the specific claim I have critiqued. Nor does it have to do with the broader problem of ecological breakdown, or the broader question of whether “green growth” is possible. In other words, yes, it’s good news that air pollution is going down, but this is certainly no sign that everything is rosy.

2. Next, McAfee turns to CO2 emissions. He points out that rich nations have been reducing their CO2 emissions, even in consumption-based terms, while continuing to grow GDP. Once again, this is widely acknowledged by ecological economists, including in the degrowth literature, and comes as no surprise to anyone (renewable energy!). Indeed, Giorgos Kallis and I address this point directly in our review of data relevant to the question of whether “green growth” is possible. I have articulated this point repeatedly.

Here, McAfee is answering the wrong question. The question is not whether GDP can be decoupled from CO2 (we know that it can be), the question is whether this can be done fast enough to stay within safe carbon budgets while growing GDP at the same time. And the answer to this, alas, is no (see here and here). More growth entails more energy use, and more energy use makes it all the more difficult to cover that demand with renewables. The only scenarios that succeed in reducing emissions fast enough to keep us under 1.5 or 2C (without speculative technologies) involve a reduction in resource and energy use (in other words, degrowth). I discuss this in more depth here and here. This 2020 review examines 835 empirical studies and finds that decoupling alone is not adequate to achieve climate goals; it requires what the authors themselves refer to as “degrowth” scenarios. This paper in Nature Sustainability comes to similar conclusions.

The key lesson here is that the less energy we use, the easier it is to accomplish a rapid transition to renewables in the short time we have left.

3. Next, McAfee turns to resources (at last!). He questions the figures from Material Footprint analysis. There are a few issues to unpack here. First, McAfee confuses offshoring and imports. MF analysis does not only look at materials embodied in production that a nation has offshored, as McAfee seems to believe. It looks at the materials embodied in all the imports that a nation consumes (i.e., the materials involved in the extraction, production and transportation of those imports). This is why MF in the United States is rising, regardless of how much of its industry is offshored at any given time.

Second, McAfee notes that MF data are based on estimates. This is hardly a revelation; indeed, this is the only way to do it, as embodied resources cannot be counted directly. But they are sophisticated estimates, and material flows scientists improve on their methods (and data availability) every year. Is it perfect? No. But it’s the best we have, and, crucially, it’s the only way to meaningfully compare resource use to GDP. Again, McAfee’s method of using domestic material consumption for this purpose (which is the basis of his book), is illegitimate. Compared to illegitimate, using MF data is a dramatic improvement.

Third, McAfee is confused about how footprints are allocated. It’s quite straightforward. The first step is to understand that the products a country imports don’t materialize out of thin air. They come from mines and factories in other countries, all of which involve resources, and those need to be accounted for. So, for instance, if the US consumes imports from China, then the US footprint includes the resources involved in the infrastructure that produces those goods, in proportion to the share of China’s economy that is organized around US consumption (and, by the same token, a share of materials in US infrastructure is allocated to countries that consume US exports).

McAfee is upset about this, and uses this example to explain why: “if my neighbors bring me a cake the same year they renovate their house, then my consumption of lumber, drywall, and copper pipe goes up as soon as I have a slice.” This example doesn’t work well, however, because the neighbour’s renovation has nothing to do with cake production. A better approach is to imagine that McAfee buys his cake from a bakery. In that case, the materials involved in the bakery should absolutely be counted as embodied in the cake. And if the bakery uses more materials and energy to make its cakes (say, bigger, more energy intensive ovens), then yes, the footprint of the cake goes up.

Of course, if one wants to avoid using MF analysis, one can look at global resource use (where trade is cancelled out), and compare this to global GDP. If we do, we see that global resource use is rising, right along with GDP. There’s no dematerialization, no green growth. In fact, the global economy has been getting more materially intensive over the past couple of decades, not less. And that’s a problem.

Global GDP and global raw material consumption

4. Next, McAfee turns to attacking the idea of ecological limits, by which I mean, the threshold beyond which continued resource use begins to cause ecosystems to break down. Ecologists who study material flows have proposed that a safe upper threshold for global resource use is about 50 billion tons per year. This is not just one paper, as McAfee implies; similar thresholds have been proposed by a number of scholars, which Stefan Bringezu reviews. Are these thresholds precise? No, they are estimates. And there’s no magic number. It’s particularly hard to arrive at a single global threshold figure, because so much depends on the type of resources, technologies, and ecosystems involved.

The authors of this research are careful to note all of these uncertainties. But they are also careful to note that we should consider 50 bn tons to be at the high end of a threshold range. So when we use 50 bn, we are being extra generous. After all, when we crossed this threshold, in 1999, we were already in trouble, in terms of habitat loss, species extinction, etc. All you have to do is look around you, pay attention to what’s happening to the planet, and it’s clear that, wherever that safety threshold might be, we’ve crossed it. Things are not going well.

Do we need better science on thresholds? Absolutely. And McAfee will be glad to know that this field is improving quickly. Researchers are beginning to distinguish different thresholds for different kinds of resources, and beginning to take account of changing ecosystems. Ultimately, we will probably need regional analysis rather than global analysis. This is an exciting field to watch. But all of this is really irrelevant to the matter at hand. The point is that we know that resource use is already too high, and we need to reduce it.

Here’s the crucial fact: there is a strong, well-documented relationship between aggregate mass flows and ecological impact (and the UN finds it is responsible for 80% of biodiversity loss). Mass flows are going up, and ecological impact is rising right along with it. McAfee tries to wriggle away from this uncomfortable fact by pointing out that we don’t know at what point resource use might actually cause global ecosystem collapse. And yes, that’s true. We don’t. It is not possible to precisely identify such a point, for any impact, including climate change. What we can say, with significant certainty, is that things are bad, they are getting worse, and economic growth is a primary driver of the problem.

With ecomodernists like McAfee, this is where the conversation always founders: they question the science on ecological limits. Once they realize that green growth is not happening and is unlikely to happen, the only thing that’s left is to question where the limits might be. Some have already tried to get us to reject 1.5C and 2C limits for global warming (an argument McAfee has endorsed). It seems to me that this represents an irresponsible attitude toward science.

Indeed, in a series of tweets, McAfee went so far as to imply that there is virtually no limit to global resource use. Global material use is now around 100 billion tons per year, but that’s “trivial”, he said, compared to the weight of the Earth’s crust, so it’s fine; there’s no reason to worry… there is no crisis. Statements like this have no grounding in science, and betray a worrying ignorance of how our planet’s ecosystems work. There is not a single ecologist that would recognize this as a legitimate claim.

It is a strange move for someone like McAfee to make. If he is so convinced that there are no ecological limits, why does he care about dematerialization in the first place? Why bother with trying to decouple GDP from resource use at all? Put another way, if McAfee is so eager to celebrate a putative reduction of resource use in the United States (which is the point of his book), why turn around and effectively deny that reducing resource use is even important to do?

*

Of course, McAfee makes this last move because he’s looking for things to attack rather than out of real conviction. Ultimately he does recognize that excess resource use is a problem, and he does want to reduce it. We share this goal. The problem is, the empirical record is quite clear that, unlike air pollution, resource use isn’t absolutely decoupling from GDP, and indeed all existing models indicate that absolute decoupling is unlikely to happen, even under strong policy conditions. We review this evidence here, but the literature has grown since: i.e., here and here… the latter paper reviews 179 studies on decoupling published since 1990 and finds “no evidence of economy-wide, national or international absolute resource decoupling, and no evidence of the kind of decoupling needed for ecological sustainability.” Here is a 2020 meta-analysis of all available data on GDP and resource use, which comes to the same conclusion.

In other words, we know that while growth does not require additional air and water pollution, it does require additional resources and embodied energy. This has been true for the entire history of capitalism, and it shows no sign of changing. Why? It’s an important question, and has been explored by a number of scholars, including here, here and here.

We can either deny this evidence, or we can face up to it. Facing up to it means rethinking the extent to which we should pursue GDP growth. Now, this is where the good news comes in. McAfee says he wants to achieve “longer, healthier lives”, improving human well-being and flourishing. That’s the goal. And here too, we agree (that’s two goals we share). But for some reason McAfee assumes that in order to do this, even high-income nations, regardless of how rich they have already become, need to keep growing their GDP, exponentially, with no identifiable end point. This is an unexamined assumption; he provides no evidence for this claim.

I get it – I used to hold this assumption too. Most people do. But the good news is that it’s not true. At least 30 years of research in ecological economics has made it clear that high-income nations don’t need to keep growing in order to improve people’s lives. They can do it right now, without any additional growth at all, simply by sharing income, resources and opportunities more fairly and investing in universal public goods. These are the interventions that matter. That’s how Spain beats the USA in life expectancy by a solid five years, and outperforms the USA on virtually every social indicator, with half of the USA’s GDP per capita. The notion that the US needs to keep growing its GDP in order to improve social outcomes is simply not supported by evidence.

By the way, we need to keep the inequality problem in mind here. According to the World Inequality Database, the richest 5% capture 46% of total global GDP. That means that nearly half of all the resources we use, and half of all the emissions we emit, is done in order to make rich people richer. In what world does this make any ecological sense? And yet McAfee has never engaged with this question.

Once we realize that we don’t need growth in order to accomplish our social goals, this makes it much easier to reduce resource and energy use, accomplish a rapid transition to renewables, and bring our economy back into balance with the living world. We should see this as liberating. And this vision is not anti-tech. On the contrary, the point is to prevent our technological gains (efficiency improvements, renewable energy, etc) from being swamped by scale effect of growth (ever-rising resource and energy demand), so that they can deliver the benefits we want them to.

Now, to McAfee’s final point: “but that would be a recession!”. And recessions, as we all know, are terrible: people lose their jobs and homes, poverty and inequality goes up, etc. Nobody wants this; and here too McAfee and I agree (that’s three). Here’s what we need to grasp, however: recessions are what happen when growth-dependent economies fail to grow; it’s a disaster. This is where degrowth comes in – to solve precisely this problem. Degrowth calls for a different kind of economy altogether: one that doesn’t require growth in the first place; one where we can reduce resource and energy use while specifically preventing unemployment and reducing inequality. The idea is to allocate resources and energy more rationally, and more democratically, to enable everyone to live flourishing lives in balance with the ecosystems we depend on.

Instead of engaging with this literature, McAfee tries to dismiss degrowth as a recession. To be frank, this is a lazy, bad faith argument. We have different words for these phenomena because, as I explain here, they are, in every respect, fundamentally different things. You can only miss this fact if you’re not reading, or if you’re intentionally seeking to mislead; either way, it is irresponsible. So, while I welcome McAfee’s engagement, this kind of claim is not helpful, and does not advance our collective understanding. My appeal to McAfee: let’s try to get beyond this sort of thing and engage more honestly with the empirical and theoretical work that has been done, so we can have more meaningful conversations. If we are going to realise our shared goals, we can and must do better.