Background

My heritage – my whakapapa – has been shaped by 200 years of colonialism: I am a woman of Indian-Pakistani descent who was born in the UK. It is therefore perhaps no surprise that, when coming to New Zealand four years ago, I wanted to make sure that my sustainability practices here reflected – and were shaped by – the indigenous peoples of New Zealand.

Working in sustainability, one understands that context is key. When we fail to identify or understand the nuanced, complex, systemic and local context of a situation, the best-intentioned solutions simply won’t solve society’s most pressing problems.

The first economic model I came across which offered an effective, modern context for our planet was the doughnut, developed by acclaimed economist and author, Kate Raworth.

To inform the local context for sustainability, I felt New Zealand needed a doughnut of its own. I have been to too many meetings held to discuss issues affecting minority groups (Māori, Pasifika, women, children) without them at the table. Clearly, the process of reimagining the doughnut needed be led by an indigenous voice – female if possible.

Enter scientist and Executive Manager of the BHW Lands Trust, Teina Boasa-Dean. Teina and I first met at the Ōhanga Āmiomio Pacific Circular Economy Summit in 2019 where she spoke powerfully about the divine kinship Māori have with the natural world.

I asked Teina to take on the interpretation of the doughnut in the hope that it would provide New Zealand with the social and environmental context for the nascent circular economy. While we have an opportunity to reflect and reset post Covid-19, the new solutions we create must be better than the broken systems of the past which have accelerated inequality and waste. If we’re not careful, circular ‘solutions’ could simply benefit those who can afford them. Using the doughnut as a framework can ensure that circular opportunities restore our ecosystems and are inclusive, diverse and distributed equitably across our cities, regions and society.

The doughnut translated into Te Reo Māori

The Te Reo Māori doughnut we created was ultimately a collaboration between four women including Jennifer McIver, Director of Wishbone Design Studio and fellow member of the Circular Economy Accelerator Advisory Board; and Tineke Tatt, a talented designer of Pacific Island descent, both of whom played a key role in the evolution and creativity of the design.

The doughnut reimagined through an indigenous worldview

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation team hosted a meeting after the 2019 Summit in London to discuss the role of indigenous people in the circular economy. Teina and I shared the draft diagram, noting it hadn’t yet had Kate Raworth’s blessing. But we didn’t just share the translation of the doughnut, we shared a second version: Teina’s reimagining of the doughnut from a Tūhoe Māori perspective, with the environment as its foundation, and social elements on the outer ring (below).

.jpg)

The Doughnut reimagined from an indigenous Māori perspective

While I was initially confronted by Teina’s ‘flipped’ version, I soon realised that this was her worldview, and all the more relevant because of this. I also understood the power of Te Reo Māori: our planetary boundaries, or ecological ceiling, becomes hā tuamātangi: the Earth’s last breath: incredibly rich and evocative.

As this depiction is the perspective of one Māori person, it obviously doesn’t represent the view of all mana whenua. There are other perspectives, including a doughnut also created in 2019, by Johnnie Freeland.

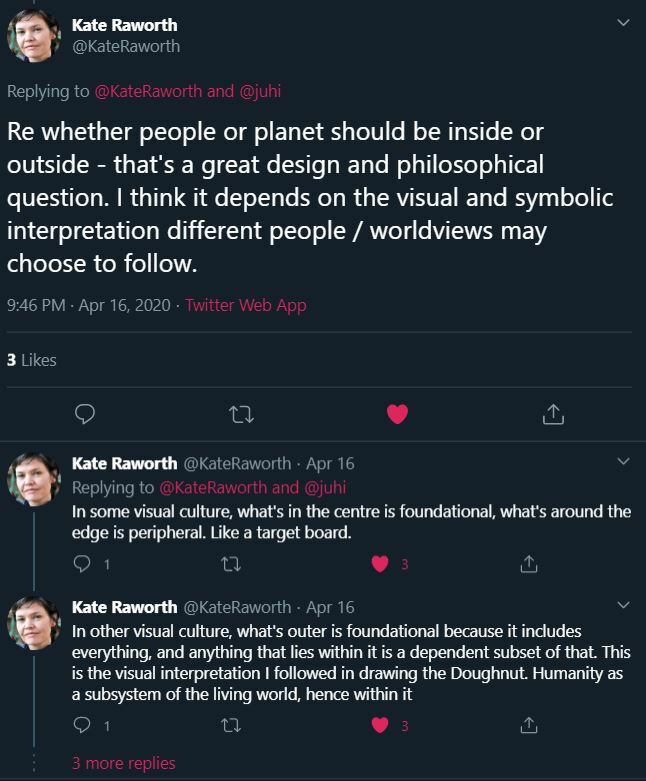

As Kate said when we shared our versions with her on Twitter:

Whatever your worldview, it is powerful to recognise that two perspectives of the New Zealand context – Māori and Pakeha – can sit side by side. It is our hope that these two perspectives, and more, spark dialogue on our journey to build a better future.

How can indigenous knowledge and practice become the foundation of resilient and regenerative cities?

Teina embodies and carries forward the wisdom of her ancestors. Her stories describe her deep connection with the biosphere which enables her to think about her existence as dependent on the biosphere, and not the other way around:

“My ability to thrive in union with Mother Nature occurs when I have not dehumanised or desensitised myself to the extent that I do not recognise that I am violating Mother Nature.”

In considering a regenerative economy as described by the doughnut, Teina says that there is no substitute for helping people become more connected with their ecology and surroundings. As a scientist, she also notes that we must make room for indigenous knowledge, explaining that matauranga Māori is a technical science and its concepts are planets away from western science. Indigenous scientists such as herself must then become teachers of this empirical, indigenous wisdom.

Teina invokes one of the most famous proverbial sayings in Māoridom:

He aha te mea nui o te ao. He tāngata, he tāngata, he tāngata

What is the most important thing in the universe? It is people, it is people, it is people.

She notes that at the time at which that particular proverb was created and imagined…

“…there was a balance between human behaviour and healthy boundaries of human behaviour in their relationship to the environment. So, at that particular point in time, when things were in more of a balance, of course people could celebrate their behaviour in relationship with the environment. Today, indigenous communities increasingly recognise that this is not the case, and having to position the earth mother and sky father at the centre of a diagram like this, makes things overt and explicit.”

Teina’s work reimagining the doughnut from a Māori perspective and her views on connection, balance and indigenous science contribute to our understanding of our context here in New Zealand. They bring an essential perspective to our exploration of the building blocks for regenerative cities.

Next steps

.png)

www.projectmoonshot.city

I am working with my partner on Moonshot:City, Priti Ambani, in a collaboration with a number of other individuals and organisations to design Aotearoa’s first Regenerative Action Labs. Drawing from the DEAL, C40, Thriving Cities Initiative methodology used for Amsterdam, we will base our Action Labs on:

- The indigenous reimagining of the Doughnut

- Indigenous Māori values and principles known as kawa, currently being refined by Teina Boasa-Dean and other Māori wayfinders. These wayfinders acknowledge the doughnut model but are now referencing a indigenous motif – a spiral – known as a takarangi. Indigenous partnership and acknowledgement of Te Ao Maori is vital for bi-cultural Aotearoa.

- Data on material, energy and asset flows

- An acknowledgement that a lot of regenerative initiatives are already underway; we aim to connect and amplify existing initiatives under a place-based, community-led vision

- A set of lenses including: biomimicry, circular economy, Cradle to Cradle, SDGs etc

- Learnings from international best practice and collaboration with leading businesses on circular business models

- A systems approach, rather than focusing on individual businesses or organisations.

Acknowledgement

Teina Boasa-Dean (Msoc.Sci, PhD completing)

To hear Teina explain the Te Reo Māori doughnut in her own words, listen to Episode 2 of our podcast Moonshot:City

This story is licensed under a Creative Commons BY SA 4.0 license. For full details see our Licensing Rules.