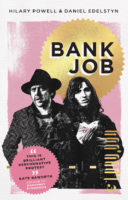

The following excerpt is from Hilary Powell and Daniel Edelstyn’s new book Bank Job (Chelsea Green Publishing, September 30, 2020) and is reprinted with permission from the publisher.

The following excerpt is from Hilary Powell and Daniel Edelstyn’s new book Bank Job (Chelsea Green Publishing, September 30, 2020) and is reprinted with permission from the publisher.

May 2019. A golden Ford Transit van explodes on London Docklands wasteland with a backdrop of the Canary Wharf financial towers. Papers flutter through the morning air and with this act £1.2 million of UK high-interest debt is cancelled. What led to this early morning debtonation, a culmination of our journey down the rabbit hole of debt and money, a quest and a questioning of the moral arguments around debt and the injustice at the heart of the current economic system?

Five years ago, mid-creative crisis and post first feature documentary film, searching for stories and meaning, Dan travelled off to the US with a camera in pursuit of the social movement Strike Debt and their ‘Rolling Jubilee’ project that buys student and medical debt for pennies on the dollar, then abolishes instead of collecting it in ‘a bailout of the people by the people’. Out of Dan’s initial curiosity as to why they would do that, came further research and his realisation that, in the words of founding member and New York University professor Andrew Ross in Creditocracy,‘Our future is mortgaged, calculated, and owned far in advance, and our democratic right to change it for the better is effectively minimized.’

From that moment on we were on a mission, with Strike Debt’s words reverberating in our heads: ‘Join us as we imagine and create a new world based on the common good, not Wall Street profits.’ How could we write off debt in the UK? As filmmaker (Dan) and artist (Hilary) we grappled with the question of how we could make a film about this that could move people to think, to question, to act and… to change. To break through the purposefully opaque language of finance, questioning and countering the overbearing narratives around debt – narratives that keep us trapped. After many dead ends and turning points, we found the answer in our home and the people who surround us. Amid the terraced streets of the London suburb of Walthamstow, our Bank Job was born as a community heist on the financial system.

It feels as if our generation has lost the right to dream

And to stand for what is right

But climbing onto the roof of my house

In the suburbs of east London

Weighed down with mortgages and other debts

Looking over a suburban landscape

Where people nursed their visions to sleep

I wanted to sumon the courage to dream again

of changing the world

And to seize my own destiny Before the hour grows too late

The Bank Job

Our plan (as they always are) was simple. We would open a bank, print our own money, sell it, raise enough money to buy up £1 million worth of debt on the secondary debt markets and then destroy it.

Step one: get a bank

In March 2018, in a former cooperative bank on a high street in our London suburb, we opened Hoe Street Central Bank (HSCB) to the public. Here we gave ourselves the power of a central bank and printed our own money. This was our very own ‘magic money tree’ whose existence has been denied by successive governments, that could print banknotes/art daily and exchange it for sterling.

Employing a crack team of local residents trained up in traditional print techniques, we made banknotes featuring local people we felt were picking up the pieces of a broken economic system, people who had value that the government didn’t recognise. Replacing the Queen and famous figures from British history, from Adam Smith to Charles Darwin, were anti-creditocracy heroes Saira Mir and family who run the homeless kitchen PL84U Al-Suffa, Gary Nash of Eat or Heat food bank, Steve Barnabis and Josh Jardine of The Soul Project youth service, and headteacher Tracey Griffiths of Barn Croft Primary School.

The bank became a hub of economic education with the ‘performance of making’ offering a tactile way into the concepts and preconceptions we aimed to tackle. The project went viral and, alongside queues down the street, the banknotes travelled across the world to locations as far flung as Singapore, Texas and lighthouse stations off the coast of Scotland.

We raised £40,000 through selling the banknotes/art at their face value (initially £5, £10, £20 and £50 notes, then £100 and £1,000 notes), with half going to the organisations featured on the banknotes and the other half into a fund to buy up and cancel (instead of collecting) £1.2 million of local predatory high-interest debt (payday, credit card and catalogue). This cancellation was a quiet process of spreadsheets refined by postcode, grappling with acronyms from GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) to the FCA (Financial Conduct Authority).

Step two: pull off a heist

Most heists aim to fly discretely under the radar. Ours was always hell-bent on making the biggest splash. If our project was to do what we intended, and challenge and be an intervention in the prevailing public narratives around debt, we needed to make a noise about it. Buying the debt was really quiet and invisible. We wanted to do something visual and dramatic. This became the ‘Big Bang 2’ – the controlled explosion of our ‘debt in transit’ van in front of London’s financial district.

Again this was a collective act – funded by a global community who purchased bond certificates printed by our bank using the same team and techniques, and promising a return on investment in the form of a piece of this literal, visceral explosion: coins made from the exploded remains.

An article in the Guardian dubbed us the ‘Rebel Bank’ and we owned it, rewriting the rules of engagement in economics, debt, art and finance. HSCB was again open to the public, exhibiting the exploded fragments of debt and money in suspended animation, and establishing itself as a place that could fill a growing void in the increasingly financialised spaces of the city – a space open to public imagination and debate, inviting people inside to share in a contagious vision of change.

Step three: film it

In Bank Job the movie – our film that all of this action becomes part of – we attempt to play with classic heist story structures and try to make sense of the unruly reality of life living the Bank Job, where the development, conflicts, crises and consequences are constant. Alongside the rupture of the EU Referendum, the UK has had three general elections in four years, and around the world far-right leaders have taken and consolidated power. At the core of the system we live within is a deep hypocrisy upheld by those it hurts most. Our children are growing, we have new friends, new focus and new fights. The world is in flames and flood, and the call and refrain of ‘people power’ ringing out across the streets of the globe brings some hope in the dark. And it has got darker since we began writing this. We are now in lockdown as the COVID-19 pandemic sweeps the world.

Step four: explode the view

Our act of debt write-off was inspired by Occupy Wall Street affiliate group Strike Debt and the multiple student debt buy-ups and public debt burnings they undertook in the US, recognising their power in educating people about how the debt system works and the power relations at play.

But at its core, the Bank Job is a project about debt and democracy or, most fully, debt and freedom – the impact at all levels of state-imposed austerity (imposed to supposedly ‘pay back’ national debt) and the crippling servitude of household debt are not only social and physical, they affect our collective imagination, our ability to dream and create a future.

In The Crisis of Democracy: Report on the Governability of Democracies to the Trilateral Commission, published in 1975, the authors identified an ‘excess of democracy’ in the educational establishments of the US, with then Republican governor of California Ronald Reagan calling the University of California, Berkeley campus a ‘haven for communist sympathisers, protesters and sexual deviants’. Evidencing this in the large- scale participation in anti-war demonstrations, the solution was found in imposing tuition fees. For, as Andrew Ross states, ‘short of armed repression, the loading of debt on to all and sundry has proved to be the most reliable restraint on a free citizenry in modern times.’

This shared awareness of how debt is a natural companion to money and that money creation by banks is fundamentally biased towards the lenders, or creditocracy, exposes the illegitimacy of certain debts and the skewed morality foregrounded by a ‘creditor class’. The realisation that debt is a social construct and shared fiction, not a non-negotiable fact, is in itself emancipating.

Step five: spread the word

Actually, ideas of debt write-offs are not that radical. We wanted our campaign to spark a bigger movement across the UK demanding economic justice. As Laura Hanna of Strike Debt said when we met on the streets of New York, ‘Things are not going to change unless people start to actually act themselves and build power at the grassroots scale and in the financial markets. We’re not going to have a system change from above.’

The BBC’s One Show described us as a ‘nice couple’, helping poor people and local causes.‘ How lovely; you gave the money to the local causes – that’s so nice’ – we knew that would be what many people thought. But for us the idea of ‘thinking through making’ is central – making visible, tactile and malleable forces that we are told to believe are immutable. We believe in an empowered knowledge through participation and action.

We are all, or we all should be, citizen poets, citizen artists, citizen economists. There is an urgent need for some far-reaching economic education, not only to help us understand the system as it is, but to take the next step in reimagining it. A step that encourages critical thinking, asks challenging questions, and grows from participation and collaboration.

What if the 2008 crash had been used as an opportunity to reshape the financial system with fresh purpose and create space to reimagine an economy that works for all of us based on economic justice? This leap of imagination lies at the heart of our Bank Job. The debt crisis cannot be corrected through local action alone, but grassroots experiments can provide both inspiration and concrete assistance to those caught at the sharp end of the problem and forced into traditional, crushing structures of stigma and blame. We wanted to challenge the highly moralising, psychologically powerful narratives of debt and money. Of Victorian notions of balancing household budgets, and religious and social sanctimonies about the sins of borrowing and the shame of debt. The project has given us hope that communities can be resilient and will stand together – that if we owe anything, it is to one another to shape the sort of world that our children can inherit with confidence. The feeling that we are not alone – or as the Strike Debt campaign puts it, ‘not a loan’ – that together we can create value that transcends the embedded debtor- creditor relationships that are ripping our communities apart.