I first met David in the makeshift living room of a building we’d stolen. Or at least I think it was then – David could often be found in such circumstances, sitting at the back of rooms, in small meetings, plotting some strange and unlikely caper with a 10% chance of coming to pass. It was 2011, during the high point of student occupations over tuition fee rises and higher education cuts, and one day, seemingly from nowhere, there was David.

I had no idea who he was. I asked a friend about the curious old American – they weren’t sure either. He spoke eloquently to a Bloomberg journalist who had shown up to report our shenanigans, but he didn’t dominate the discussion. He pitched in like everyone else with the minutiae of cleaning and joking, plotting and worrying; conducting himself as I would come to know him: generous and playful, modest without being self-effacing, happy, just to be surrounded by oddballs and activists intent on making the world a more magical place.

Some people call themselves anarchists because it fits their opinions on a graph or because it sounds cool. But as David was at pains to explain, anarchism was a praxis: it was the doing, and the living of the thing, which counted. As his Twitter bio had it: “I see anarchism as something you do not an identity so don’t call me the anarchist anthropologist”. No matter how smart he was, or how esteemed he became, he was always in the mix. Nothing was too small, no company too insignificant. He lived his ideals with an unusual consistency.

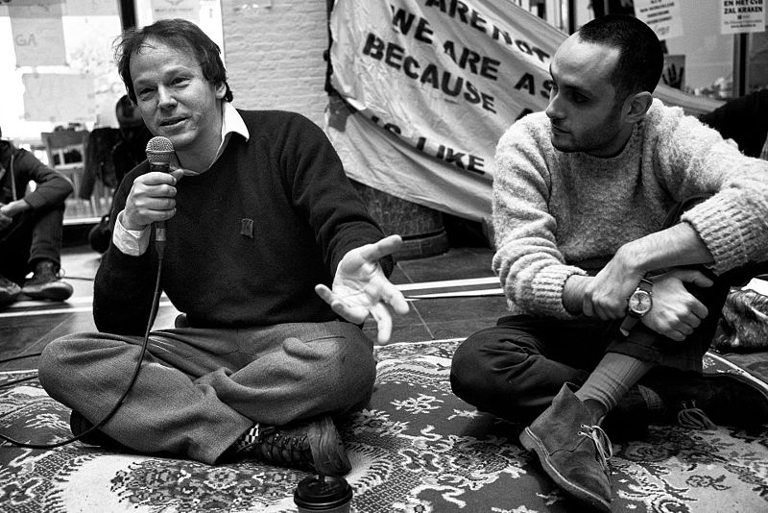

On stage he was the same – excited to debate and throw out new ideas, but always bringing the room in, rather than preaching to it. I think he enjoyed the limelight when he got it – notably after the publication of his most successful mainstream book, Debt, but it never changed who he was. You’d bump into him on the street outside a left-wing event (usually shuffling off to find some Chinese food) and he’d immediately include you in whatever conversation he’d just been having in his head:

“Fractal theory, y’know?”, nodding inscrutably.

“…Sure, David!”

And there was always a conversation happening, always a new idea. When I interviewed him (along with filmmaker Ellen Evans) for The White Review, I spent three booze-filled hours receiving the full force of David’s brain as he invented theories on the fly, segued into the politics of Madagascan magical rites, came back to a playful anecdote from his childhood and finished off with his inimical off-beat laugh.

David loved to collaborate with everyone around him, but as a thinker, he was utterly singular. His writing had offered accessible, quirky and original ways of looking at history, politics, culture and economics. He was not a ‘forensic’ scholar obsessing over detail (a bugbear of his detractors) but was drawn to the big questions that most academics feel you’re not allowed to ask anymore – or shouldn’t risk trying. The full title of his most famous book: Debt: The First 5,000 Years captures that chutzpah.

The breeziness of his style could also belie the depth of his scholarship. Who else would produce articles entitled: “On the phenomenology of giant puppets: broken windows, imaginary jars of urine, and the cosmological role of the police in American culture”, or offer meditations on the radical meaning of scatology? Who else could penetrate the mysterious morality around debt, or question why the hell so many of us do jobs we don’t even believe should exist? His best essays unpick stories which have solidified into lazy consensus, pulling at their threads until the whole thing unravels and a totally different conception of who we are, where we’ve come from, and what is possible for human relations, emerges.

David was so influential for my generation not just because we read his work (we all did) but because he was always actually there: dropping a phone call or email, turning up at the pub, hanging out at a house party. He was always ready to see how you were doing or offer thoughts on a project or get excited about whatever it was you had to say or write (even if it wasn’t that good!). He seemed to prefer the company of younger activists, who I suspect chimed with his natural optimism and inclination to be out and about in the world. With anyone else, that might sound weird, even creepy. With David it just wasn’t. But it did get him into bother at times – sometimes coming in for flack as he became entangled in the fractures which are sadly common to young activist life, and from which a more aloof figure could have easily steered clear.

There could be something almost childlike about David, and I felt protective of him at times, despite the gulf between our ages and experience. Whatever guards we put up between ourselves and the world as we age, David had fewer of them.

He was bad at the internet. Wounded easily by the hostile comments which are the standard fare of public prominence, he would take it to heart and lash back. I suspect people sniped at him imagining they were gunning at a big shot who wouldn’t much care what they said, but David didn’t have those airs and graces; everything could hurt him equally.

His effective blacklisting from American academia brought him to the UK, where he found a home first at Goldsmiths – which he liked because it was “kinda kooky” – and then at the LSE.

We lost touch over the years as I left London and became more disaffected with the activist scene – unlike David’s, my optimism was more easily tarnished. We’d chat on the phone occasionally but our commitment to meet up when I was next in town never materialised, with only myself to blame. How much I regret that now. How much I could do with his buoyancy, his affirmation, his instinctive sense for how it was all worth it, all meant something, whatever it was. Generosity is in short stock right now; losing David is like losing access to the main supply.

I can’t bear the idea that there will be some awkward socially distanced funeral, presided over by an online tableau of fragmented faces. That wasn’t David. I want there to be a bloc of sparkly anarchists, giant puppets, ancestral rites; I want the walls painted with unicorns and Graeber slogans about the revolutionary power of the imagination. I want a Buffy the Vampire Slayer cosplay troupe, delicious Chinese food, and a commemoration event which spills out into the streets, somehow mysteriously culminating in the total, benevolent collapse of global capitalism. I want the bullshit jobs to end, the debt to be forgiven, and the riot cops to blink, dumbfounded, in the mirror, before dumping their uniforms in the bin. Rest in power, peace and possibility, David – your legacy will spill out into the future of this world in so many untold directions, so many beautiful, iridescent ways.