In a recent committee meeting at my institution, I heard a colleague say: “Our job is to prepare students for the world.” This comment wasn’t intended as an earth-shaking revelation, but it nevertheless caught my attention and got me thinking. On the surface, the idea appears to be simple and non-controversial, even banal. Those of us who are associated with higher education do tend to assume that we are in the business of preparing students for the world. Upon closer examination, however, the matter turns out to be rather complex.

Generally speaking, we can only prepare our students for the world to the extent that we know the world ourselves; for the vast majority of educators, this means the world of the immediate past. But preparing students for the world entails helping them develop the type of knowledge, skills, and attitudes that will allow them to meet the challenges that they are most likely to face, not the challenges that we faced. This, in turn, requires that educators are reasonably well-informed regarding the world as it will be over the next half century—i.e., the world in which our current students are going to spend most of their lives. It follows that if we fail to take into account the specific ways in which the world is changing, we’ll also fail to prepare our students for the world in which they’re going to find themselves. In other words, if we don’t systematically think about how the world is going to look like in the coming decades, and if we don’t continually change our pedagogy in light of what we’re learning about the world’s future, our students are likely to discover that their education was utterly worthless insofar as it failed to prepare them for the world.

As a matter of theory, we educators are well aware of the imperative to constantly adjust what we teach in accordance with how the world is changing. In practice, however, most of us are no less resistant to change than members of any other profession. Both personal and institutional factors conspire to keep things moving along their established trajectories, thereby making significant change difficult to imagine and slow to implement. Thankfully, this inefficiency in adjusting to change does not prove fatal for most institutions—provided the world itself changes in a relatively predictable way and at a relatively predictable speed, thereby allowing our pedagogical practices enough time to catch up with reality.

The predicament we are facing today, however, does not fit well in this narrative. There are two main reasons for this: first, the world is currently changing at a speed that is faster than ever before; and second, the overall direction of the change is such that it is making life increasingly desperate for increasingly large segments of the planet’s inhabitants. As a result, many of our fundamental assumptions about the world are quickly becoming obsolete. Consider, for example, that we can no longer assume that the earth will continue to have a stable and benign climate, or that the national and global economies will continue growing indefinitely, or that the land and oceans will continue to feed more and more people, or that technology will continue to improve in its ability to solve our problems without creating new ones, or that human population will continue rising along with everyone’s standard of living, or, indeed, that our basic needs will continue to be met without any disruptions. Instead, we are witnessing the slow but inexorable disintegration of our quasi-religious faith in the story of infinite material progress as capitalist hubris collides against the biophysical limits of our planet. It has been well understood for a long time that civilization in its present incarnation is not sustainable; today, it is time to acknowledge that the world is currently experiencing the initial stages of what might be called socio-ecological collapse. Given what we know about how things work, it is time to acknowledge that we are facing a situation that does not get better with the passage of time—at least not in the foreseeable future.

What does the current state of the world mean for educators? Given that the natural and social systems that make up our world are in a state of ongoing or imminent collapse, it should be clear that the world in which our students are going to spend most of their lives will be very different than the world of the immediate past—and not in a good way. This means that we can no longer assume that our students will face the same kind of challenges that previous generations had faced. Consequently, if we want to prepare our students for a drastically different world, the world in which they will actually spend most of their lives, then we must teach them in drastically different ways. Facing an unprecedented situation requires the ability to think, imagine, and act in unprecedented ways.

Since governments and corporations, as well as the majority of our fellow humans, are unlikely to change their ways in the short-term, it is imperative for people associated with higher education to take some unconventional but necessary steps within their respective zones of influence. I believe educators have a special responsibility in this context, which stems from two sources: first, the unusual privilege that society bestows upon academics and other intellectuals, including the time, opportunity, and resources that make it possible for us to see what’s coming a little sooner, and a little more clearly, than others; and second, the demand of our vocation to train and educate students in ways that will support their total well-being. In effect, educators are responsible, more than any other segment of society, to take seriously both the current global trends and the most likely future scenarios as we go about our daily business of preparing our students for the world.

What, exactly, is required of educators in a time of collapse? I suggest that we begin by grappling with a few fundamental questions. For example: Is helping our students become productive members of the economy still a meaningful goal, given how the global economy is implicated in the destruction of all that we hold dear. If our job as educators is to prepare our students for the world, how well do we actually understand the world that our students are destined to inhabit? If our current understanding is inadequate, what do we need to learn so we can fulfill our responsibility as conscientious guides for the next generation? After we have acknowledge that the world is in a state of socio-ecological collapse, we would need to come to terms with the fact that our students are destined to live in a much impoverished, troubled, and desperate world. This, in turn, should lead us to face another set of questions. For example: What should be the purpose of education in a time of socio-ecological collapse? How are we to prepare our students so they can meet, in ethical and humane ways, the challenges they are likely to face? What will be the cost to our students if higher education continues on its present path while administrators and educators keep trying to maintain business-as-usual?

The assumption that the future is going to be just like the past is untenable. If we keep educating our students on the basis of this assumption, then that means we’re not preparing them for the world. Instead, we are unwittingly encouraging a cynical attitude among those of our students who do have a sense of where the world is headed. As for those who are still blissfully unaware of the challenges coming their way, we are essentially setting them up for shock, disillusionment, and suffering.

As educators, our insistence on staying the course in a time of socio-ecological collapse is a betrayal of our vocation as well as of our students.

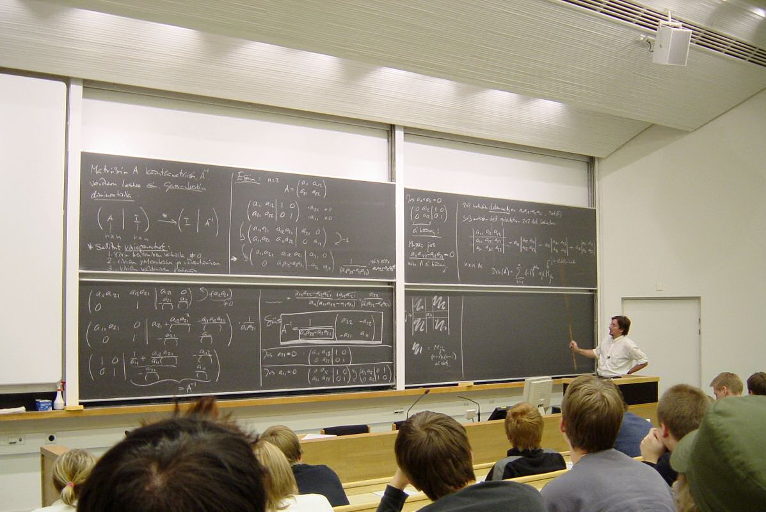

Teaser photo credit: By Tungsten – photo taken by Tungsten, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=171641