Half a century ago, the Secretary of the Interior called for a Project 76, a set of policies coinciding with the Bicentennial of the American Revolution and aimed at creating an urban renaissance by the year 2000. It didn’t happen, but his ideas may resonate even more today than they did then.

“An increasing gross national product has become the Holy Grail, and most of the economists who are its keepers have no concern for the economics of beauty.” –Stewart Lee Udall, 1968

During the Covid-19 pandemic, I’ve been developing a documentary film project about Stewart Udall, America’s Secretary of the Interior during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. I have always admired Udall as the exemplar of a public servant who put the nation’s needs above his own. I interviewed him once in 1988, but it was when I read of the 100th anniversary of his birth (January 31, 1920) that I grew determined to celebrate his life in film. I was surprised to discover that no film biographies of Udall had been produced, with the exception of short tributes. So I went to work researching his story. I’m calling the film Stewart Udall and the Politics of Beauty.

I already knew quite a bit about Udall and his career at Interior, promoting what became many of our landmark environmental laws, establishing a host of new national parks and wilderness areas, and first supporting, then stopping, power dams planned for the Grand Canyon. He has been called the most effective Interior Secretary in America’s history, and the Department of the Interior Building (as well as the easternmost point in the U.S., Point Udall in the Virgin Islands) is named for him.

But as I read biographies by Thomas G. Smith and Scott Raymond Einberger, I became aware of Udall’s much wider interests—in racial justice, environmental justice (including his fight for the victims of uranium mining and atomic testing), the arts and humanities, and, later in his life, the global climate crisis. I was surprised by how many of his concerns are still relevant today. I began to talk with his children, friends and former co-workers and developed a film proposal, and a Facebook page which led to new connections. I read and watched whatever I could find about him, growing more convinced by the day of the importance of his contributions. But I still thought of Udall as a rural westerner whose driving passion was the preservation of America’s priceless public lands.

UDALL’S URBAN RELEVANCE

UDALL’S URBAN RELEVANCE

Then, a conversation with the prominent presidential historian Douglas Brinkley added a new wrinkle to my thinking. After reading my initial film proposal, Brinkley, who is currently writing a book on the rise of environmentalism during the Kennedy/Johnson/Udall era, suggested that what was missing in my vision, and what would make the story even more currently relevant, was Udall’s passion to address the ills of urban America, not just the public lands issues usually associated with Interior secretaries.

A re-reading of Udall biographies confirmed that I missed this key element of his life’s work. Einberger in particular led me to a somewhat forgotten text of Udall’s (he wrote nine books) called 1976: Agenda for Tomorrow. I ordered a copy through a used book seller. When it arrived, I was surprised to find that it was a signed original edition. “For Maurice Knee, Guardian of the land of monuments,” the inscription read, “with the warm regards of Stewart and Lee Udall. June 1969” A Google search revealed that the “land of monuments” was Monument Valley, Arizona, where, in those days, Knee ran a trading post. I delved into the book, and quickly realized that Udall’s thinking was prescient and his words prophetic. The shock of recognition and the relevance for our own age was palpable.

Udall with LBJ and Lady Bird Johnson Source: Wikimedia

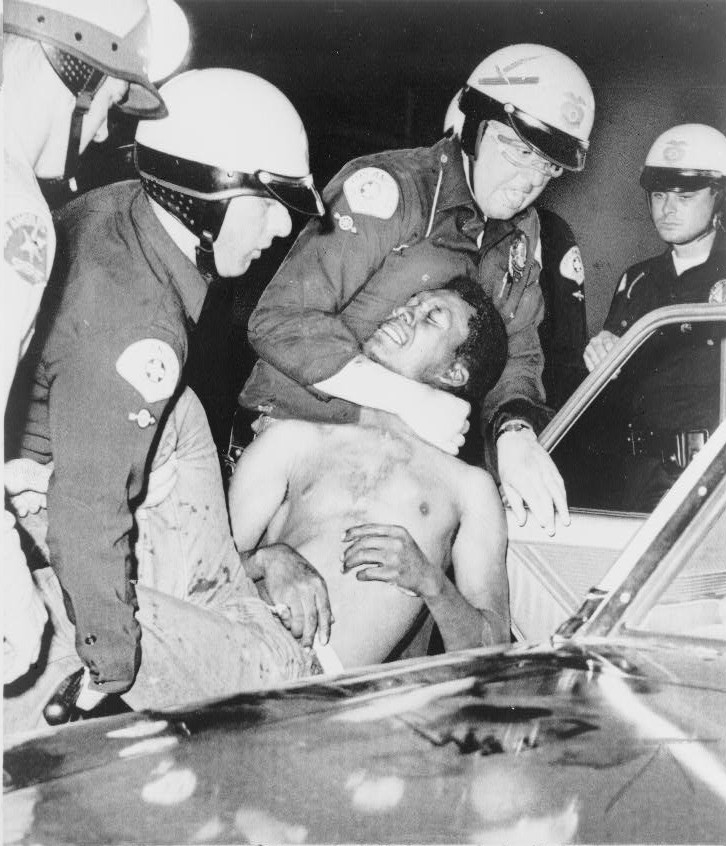

He wrote the forward in July of 1968. It was a time much like our own, except that we had a president who hoped to unite the country rather than divide it. The task was daunting. Much like Minneapolis, Portland and Seattle in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder, our urban streets in Udall’s time were engulfed by a series of insurrections that began in Harlem in July of 1964. “In the heat of the summer,” folksinger Phil Ochs wrote about the Harlem riots, “when the pavements were burning, the soul of a city was ravaged in the night…Now no one knows how it started, why the windows were shattered, but deep in the dark someone set the spark…”

The cause was quite clear and the images easily recognizable to us today. An unarmed Black teenager was shot and killed by a white police officer in clear view of a crowd of people. The ensuing violence resulted in one death, more than 400 arrests and extensive property damage. Ochs expressed the protestors’ anger that, then as now, Black lives did not seem to matter—”…we’ve been down so long, and we had to make somebody listen.”

The next summer, another confrontation between police, young men and a pregnant Black woman resulted in a conflagration that dwarfed Harlem’s by comparison. When the “Watts riots” were over, 34 people were dead and 3400 had been arrested. More violence erupted in 1967. In mid-July, a police beating of a Black man resulted in 26 deaths in Newark, and only a week later, Detroit exploded, leaving 39 dead, including 16 police officers and soldiers. More violence followed in the wake of the murder of Martin Luther King in April of the next year, followed by a “police riot” at the August Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

Watts riot, 1965 Source: Wikimedia

A 1968 study of the upheavals by the Kerner Commission found that absence of economic opportunity had turned urban ghettos into powder kegs. “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal,” the report declared.”What white Americans have never fully understood — but what the Negro can never forget — is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.” Moreover, the report condemned racism in the media for hiding the truth from White eyes.

MOVING BEYOND WAR

Meanwhile, a war raging in Vietnam brought campus unrest to a crescendo. And many hopes were shattered by the assassination of presidential candidate Robert Kennedy in June 1968, following a victory in the California primary that would likely have carried him to the Democratic nomination. Udall was grieving deeply at the time; Bobby had been a dear friend. Udall opposed the war. His brother Mo was among the first members of Congress to condemn it publicly. But Stewart expressed his thoughts only as private remarks to the president and in the cabinet. He was accomplishing much as Interior Secretary and knew he would not keep his job if he took on Johnson in the open.

Then, in the book, 1976: Agenda for Tomorrow, he made his disagreement known even though he was still in the cabinet. The war in Southeast Asia and money spent on weaponry, he warned, was taking away much-needed resources from our failing cities. While he’d fought proudly in World War II, Udall frowned on militarism; indeed, in 1962 he had traveled to Soviet Union with poet Robert Frost, meeting with Nikita Khrushchev in an effort to curb nuclear weapons proliferation. A few years after leaving his position as Interior Secretary, he would take on another kind of fallout from the arms race—the sad fate of “downwinders” and Navajo uranium miners who were victims of cancers caused by atomic radiation.

Our cities, Udall argued, were neglected, plagued by structural unemployment, an inadequate housing supply and financial redlining. They were hollowed out by white flight to the suburbs, and sometimes riven by violence. They suffered particularly from two central problems, the “nationwide infection of racism,” and a political system that gave disproportionate power to rural districts and states, especially in the South. The result was a “paralysis of politics” that prevented federal investment in cities. “Negro [Udall’s language reflects the common usage of his era] removal” was more prevalent than real urban renewal. “Congress, in the postwar years,” he wrote, “was anti-Negro, anti-city, anti-education, anti-culture, and incapable of thinking in terms of national goals for an overall environment of quality, human equality and ecological balance.” It seems that on this count the rural/urban divide has widened over the past half century.

Moreover, he wrote, market-driven economics “accepted poverty and slums as inevitable incidents of American life.” Whole areas of cities were sacrificed to the automobile. While Japan and other nations built fast and efficient new public transit systems in the postwar era, Americans abandoned theirs for the private car. Freeways carved up neighborhoods. Udall calculated that a reduction of 25 percent of city streets and parking lots could double the size of parks and open space. Billions were spent on highways “so people can ‘escape’ to the beaches,” but “only pennies for the parklands so desperately needed in every neighborhood.”

LA freeways Source: Wikimedia

Udall did not spare environmentalists from his critique. “The quiescence and narrow perspective of the postwar conservation movement did little to redirect the urbanization and industrial growth that would befoul the air, turn rivers into open sewers, and overrun the countryside with ‘slurbs’ and scars and eyesores,” he charged. “The bulldozer, the billboard, and the belching smokestack were the authentic emblems of postwar progress.”

Cities also fell victim to gun violence, Udall wrote, in a passage that recalls our recent spate of school and other mass shootings; in 1967, guns accounted for eight times as many homicides in Houston alone as in all of Great Britain. “The squalor, the ugliness, the inhumanity, and the police squads at the ready, tell us that the failure of American urbanization is now a judgment of history.” This sad reality, Udall observed, extended beyond the urban ghettoes to Indian reservations and many rural areas as well. An urban renaissance would also need to address the pain outside the cities.

CHALLENGING THE GOSPEL OF GROWTH

In addition to racism and the unregulated market, our values held up quantity over quality, Udall observed. We worshiped “the gospel of growth,” both of production and population. “We are still held in thrall by the idea of growth for its own sake…This outworn and dangerous growth gospel must be rejected,” Udall declared. He called for a new index of quality of life and the environment that would supersede our reliance on the Gross National Product (now, in a slightly different form, referred to as the Gross Domestic Product). In this he echoed Bobby Kennedy’s view that “the Gross National Product measures, in short, everything except that which makes life worthwhile,” and that of Lyndon Johnson himself, who warned against “unbridled growth” in his 1964 “Great Society” speech.

Consumerism, Udall felt, was a hollow philosophy, and overpopulation promised a society where “all forms of outdoor recreation will be rationed…the national parks and seashores will be severely rationed.” “Interest in wild things and open country” would be extinguished and countless species “of plants and animals, their habitats destroyed, will have disappeared.” Large wildlife, he warned, needed sufficient land, removed from human beings, to thrive.

His warnings have been realized. Visitation is now rationed for many popular trails and much more is needed; a recent Seattle Times article reported that rangers counted 999 hikers at Colchuck Lake in Washington State’s Alpine Lakes Wilderness on a single Saturday and hauled out two hundred separate piles of garbage and human waste. Meanwhile, the United Nations estimates that a million species of plants and animals may become extinct in the next decade.

We Americans, Udall wrote, believed in two dangerous myths, “the Myth of Resource Superabundance and the Myth of Scientific Salvation.”Our population growth was actually more threatening to the earth than that in poor nations because we each consume so much more. If we didn’t waste our wealth “on idle displays of conspicuous consumption…illusory arms races or dubious military actions,” he suggested, we might “make all cities cathedrals for everyday existence.”

THE CITIES OF TOMORROW

Toward that end, Udall proposed a program like the New Deal that would “provide full employment as the humane use of human beings, not merely more jobs [my emphasis] …conditions that will create social health…balanced cities, not merely more housing” [something to consider as we respond to the epidemic of homelessness], and “liberation from the congested prison of private wheels by the creation of fast and quiet public transportation.” The program should be as concerned, he said, with conditions on Indian reservations as “the barrios of East Harlem. It should be as interested in the revitalizing of small towns as in the renovation of the largest metropolis.”

Moreover, the new, balanced, cities he proposed, would “put people first,” avoiding the dominance of squared-off high-rise office towers, a cold architecture that depresses the spirit driven by “our readiness to employ steel without style and put technology before taste.” Only in Washington DC, he wrote, did “the spires of cathedrals still dominate the horizon and deny the message of the skyscraper that we are pre-eminently and everlastingly a commercial civilization..”By contrast, he lauded the human scale of many European cities.

Beautiful European cities make room for people. Source: Wikimedia

The idea of enhancing beauty, both natural and human-designed, was central to this thinking, which Udall referred to as “the emerging economics of beauty.” It would provide parks, fountains, plazas as gathering places, and public art, elevating the soul of America. “Just as Franklin Roosevelt sent unemployed youths into the devastated woodlands to replant the forests,” Udall wrote, “we should launch an urban clean up corps to roll back blight, reclaim public beauty…” and, “if we dare have faith in the aptitudes and aspirations of our own people—and especially the younger generation—we can have a blossoming of American genius and art that would truly transform the face and character of our country.”

As a substitution for the wasteful pleasures of consumerism, Udall suggested a new educational emphasis on the arts and humanities to increase interest in less consumptive activities. Surprisingly for someone who grew up in a small ranching town in the Arizona desert, Udall had a passion for high culture, bringing poets like Robert Frost and Carl Sandburg to Washington, promoting regular artistic performances by world masters and supporting the establishment of the national endowments for the arts and humanities. His wife Lee filled the Interior building with Native American arts and crafts and pushed him further in his support. He wrote poetry himself, as several of his children still do.

Such a new focus for education, Udall suggested “may well teach us to cultivate the gentler sides of our nature, to awaken to the arts, and to sense the lasting satisfactions of altruism…education is more than preparation for given kinds of work.” “Enlarged opportunities for education,” he wrote, might also “become preoccupied with the more aesthetic aspects of nature.” In addition to an increase in wilderness areas and national parks, which he also advocated, we would need to put much more emphasis on bringing the wild into the city itself, with nature trails, urban forests, and streams clean enough to swim in.

But of all the contemporary reminders of Udall’s almost-clairvoyant perspicacity, what is most surprising are his warnings about the potential dangers of climate change, something very few public figures were talking about 52 years ago. We must reduce our burning of fossil fuels, he argued then, or “we may alter the heat-absorption capacity of the atmosphere and cause the earth’s climate to grow warmer…which could melt enough of the world’s glaciers to cause the inundation of all coastal cities.”

Miami already knows what he means. Worse, the extreme weather events now generated by global warming threaten vast areas of the United States and the rest of the world. Fires in California burned a million acres in just the past week and Death Valley hit a record 130 degrees—twice. Consider what it means that Udall’s warnings and those of many scientists were ignored for so long, and by some, still are.

IT’S NOT TOO LATE

But 1976: Agenda for Tomorrow was not a doomsday book, and this is not a doomsday article. Udall proposed dozens of remedies for the ills he revealed; some of them, like his Land and Water Conservation Fund, have brought parks and trails, nature centers and cleaner water to many cities and towns. The Fund was recently made permanent, as part of the Great American Outdoors Act. One of Udall’s first ideas as Interior Secretary, the LWCF was originally passed in 1964, four years before he called for its expansion in his book. With federal transportation funds, many cities did install fast new light rail transit systems.

But most of the agenda he proposed remains to be realized, including the dream of racial justice that he weaves throughout its pages. It is simply heartbreaking to see violence in our cities today because the deep-seated racism Udall deplored has still not been adequately addressed. In his book, Udall called for a renewal of American democracy with greater citizen participation, and more opportunities to engage. Instead, we seem to be retreating from that promise. The Voting Rights Act, passed under Lyndon Johnson, has been weakened by the courts, amid state and local efforts to suppress votes—including voting by mail. And recent years have witnessed an epidemic of gerrymandering so odious that in Wisconsin, for example, Democrats won 54 percent of the 2018 State vote yet only 36 percent of the legislative seats.

Bobby Kennedy, whose lifeblood drained away on the floor of Los Angeles’ Ambassador Hotel only a month before Udall finished 1976: Agenda for Tomorrow, wrote a book for his campaign inspired by the words of a Tennyson poem: “Tis not too late to seek a newer world/It may be we shall touch the happy isles…” Today, we would do well as a nation to re-read Udall’s book and bring its broad vision back into our narrowed and polarized politics. If, as I hope with all my heart, the nightmare of the Trump presidency ends in January, and we can also break free of the impediments of Covid-19, it will be time for our nation to update Udall’s sweeping vision, not merely “return to normal.”

With ideas like the Green New Deal, or the “Beauty New Deal,” which the Maryland-based Bread and Roses Party has proposed, we should be able to write another volume—2026: A New Agenda for Tomorrow. If we take its—and Udall’s—ideas seriously, implementing them in the years before the United States turns two hundred fifty, Americans may yet live in a newer world by 2050, amid cities and towns that are happy isles in a beautiful, sustainable, just and compassionate nation.