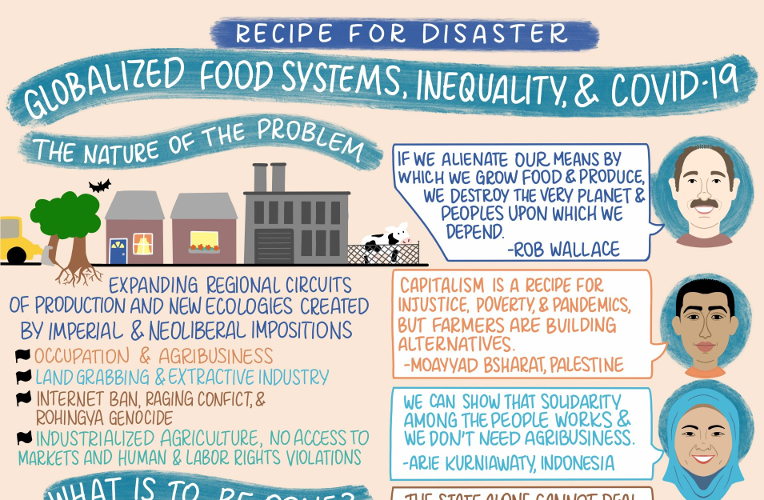

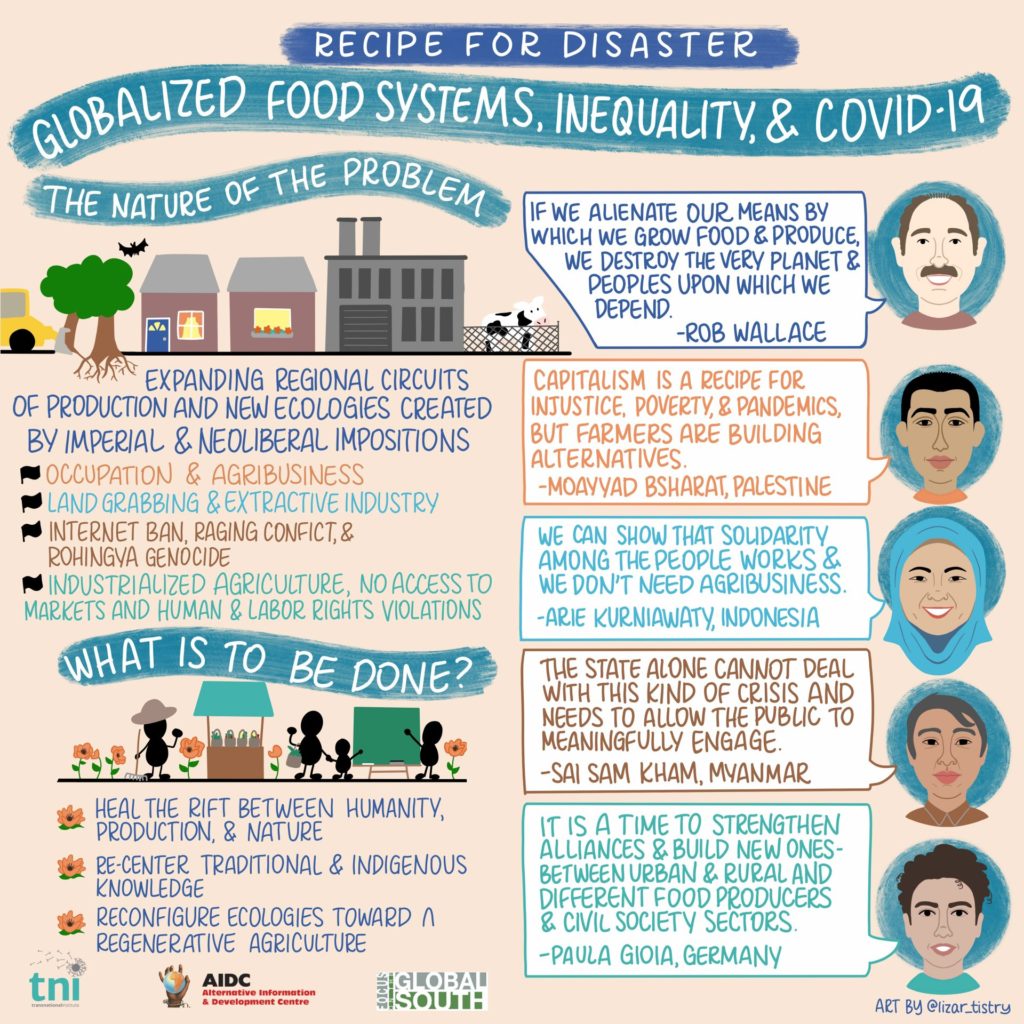

How can we begin to understand the complex relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and our food systems? How is this crisis impacting communities and transformative strategies for a future founded on international solidarity, agroecology and food sovereignty? Our recent webinar A Recipe for Disaster: Food systems, inequality and COVID-19 addressed these questions and more.

Rob Wallace outlined the situation so far and posed a number of questions that served as starting points for the discussion that followed.

More than a quarter of current recorded global cases of COVID-19 are in the US with large outbreaks in Europe and the Middle East. Cases in the Global South are on the rise, in a context of lesser public health capacity, fewer household resources to shelter in place and a greater number of underlying health conditions. In the most impoverished areas of the Global North and South matters including access to food are becoming arguably more pressing than the virus itself.

We are seeing reversals including Britain accepting shipments of masks from Vietnam, Cuba sending doctors to Italy and Senegal turning around tests in four hours, while the same tests take ten days to process in the US. These telltales are underway during what world-systems theorists describe as a major shift in the cycles of capital accumulation which have structured much of the world order for the past 500 years. The US is on the tail end of its cycle of accumulation, cashing out and turning capital back to money for the wealthiest. Rob described the recent US defunding of the World Health Organisation (WHO) not as an exercise in imperial might but a capitulation of the American role of keeping the global system on the same developmental path despite the unsustainable destruction this path represents. With its individualized public healthcare, the US now barely has enough hospital beds and equipment for normal operations let alone the resources necessary to pursue the scale of disease suppression that this outbreak demands.

China, in contrast, having invested in building the infrastructure it needs to turn money into capital, moved to eradicate COVID-19 from Hubei by deploying 40,000 medical staff and conducting comprehensive contact tracing and testing.

Addressing why some countries have escaped the worst of the outbreak, Rob noted successful government responses that both prepare a country during the advanced warning stage and sees the shared commons as still part of the purview of governance. Taiwan and Iceland have been effective by means of aggressive testing, tracing and isolation of cases. Vietnam provides most of its population with comprehensive health care and has doctors and nurses in every community. Unlike in the US where the federal government set off a black market bidding war for ventilators between states, there are few if any reports from Vietnam of price gouging, panic buying or hoarding.

Economically, disease and deficits are interacting. Those countries worst affected will find themselves further in the fiscal hole once the economic fallout begins in earnest. Efforts to fix the outbreak and economy simultaneously see attempts to push the two crises onto the indigenous and poorest workers worldwide. Brazil and the US are already planning to reduce the criminally low wages of immigrant farm workers as a ‘pandemic relief’ for agricultural companies.

These cycles of accumulation – the US cashing out while China ramps up – have impacted the very origins of COVID-19. Over the past 40 years China chose to engage in massive shifts in land use and migration to feed and pay its population. These shifts had a considerable impact on decoupling and then recoupling traditional ecologies into new configurations that have had a profound effect on both the economy and epidemiology. Post-economic liberalization in China has seen the rise of multiple strains of new influenza including H5N1, H6N1, H7N9, H9N2 as well as SARS1 and now African Swine Fever which killed half of China’s hogs last year. The genetics of the virus SARS2 show it to be a recombinant of a bat coronavirus and a pangolin strain that subsequently attuned to the human immune system either before or during the Wuhan outbreak.

Clearly agriculture had a role to play in this process, despite China moving towards an official position that it did not. Somehow the virus got from the many coronaviruses circulating among a variety of bat species in central China into Wuhan. How do you explain a move from bats to pangolins through perhaps another intermediary species such as hog into humans without bringing up agriculture or logging or mining? In all likelihood, an expanding regional circuit of production maneuvered both the increasingly formalized wild food sector and industrial livestock production further into China’s hinterlands where both sectors increasingly encountered bat reservoirs. These peri-urban loops are growing in the extent of population and can increase the interface and spillover between wild non-human populations in newly urbanized rural areas. These new geographies also reduce the environmental complexity within forests that help to disrupt the transmission of deadly viruses.

This regional circuit of production of COVIDs likely origins – forest to peri-urban to city – is reproduced around the world, offering a broader framework by which to consider outbreaks. SARS1 and SARS2, Ebola, Zika, Yellow Fever, African Swine Fever, Avian Swine Influenza, Nipah virus and Q fever among others all originated or reemerged somewhere along such expanding circuits of production, whether in the forest or the new peri-urban continuum or in factory farms and processing plants near or in cities. Many such new ecologies are driven by imperial or neoliberal imposition. Infectious diseases are not merely the matters of the virus itself but also the context in which they emerge. Coronaviruses are only one of many pathogens developing in such an agro-economic context.

We must protect the forest complexity that keeps deadly pathogens from infecting livestock and human hosts that then enter the world’s travel network. We need to reintroduce livestock and crop diversities and reintegrate animal and crop farming at scales that keep pathogens from ramping up in deadliness. We must allow our food animals to reproduce on farms, restarting the natural selection that allows immunities evolution to track pathogens in real-time. These are many of the very practices that the indigenous and smallholders of the world engage in as a matter of course in their everyday cultivation. Can we scale these out specific to the needs of people around the world and as a consequence make a world in which there are many worlds?

Arie Kurniawaty of the Indonesian feminist organization Solidaritas Perempuan (SP), working with women in grassroots communities across the urban-rural spectrum described how, in Indonesia, the population is particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 due to impoverished living conditions, inaccessible health services and the high number of people with tuberculosis and diabetes. Due to a lack of medical personnel that can provide sexual and reproductive health services since the pandemic, there are also reported cases of pregnant women feeling anxious and having to postpone their routine checks. Indonesia is particularly vulnerable to natural and ecological disasters including floods and volcanic eruptions. Following the 2018 earthquakes, tsunami and liquefaction in Sulawesi, survivors are still living in temporary shelters with poor water and sanitation facilities. Despite being very rich in agriculture and fishing resources, Indonesian food producers – particularly small scale and traditional – are constantly threatened by corporate power, land grabbing and extractive industries. Even amid the pandemic these damaging infrastructure projects continue and workers do not have enough protection. Solidaritas Perempuan is documenting the impacts of COVID-19 as well as the government policies to address the crisis that are proving biased towards the middle class and do not take into consideration the diversity of the population. Physical distancing and large scale restrictions recently implemented in some big cities have already resulted in millions of people losing their jobs. Traditional markets have no support from the government to implement safety protocols and are subsequently labeled as harmful and unhygienic. Women make up most of these market sellers and buyers. In coastal villages, fish markets have been closed so women are struggling to sell their fish and shells. In turn this economic difficulty has created an increase in domestic violence.

Arie Kurniawaty of the Indonesian feminist organization Solidaritas Perempuan (SP), working with women in grassroots communities across the urban-rural spectrum described how, in Indonesia, the population is particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 due to impoverished living conditions, inaccessible health services and the high number of people with tuberculosis and diabetes. Due to a lack of medical personnel that can provide sexual and reproductive health services since the pandemic, there are also reported cases of pregnant women feeling anxious and having to postpone their routine checks. Indonesia is particularly vulnerable to natural and ecological disasters including floods and volcanic eruptions. Following the 2018 earthquakes, tsunami and liquefaction in Sulawesi, survivors are still living in temporary shelters with poor water and sanitation facilities. Despite being very rich in agriculture and fishing resources, Indonesian food producers – particularly small scale and traditional – are constantly threatened by corporate power, land grabbing and extractive industries. Even amid the pandemic these damaging infrastructure projects continue and workers do not have enough protection. Solidaritas Perempuan is documenting the impacts of COVID-19 as well as the government policies to address the crisis that are proving biased towards the middle class and do not take into consideration the diversity of the population. Physical distancing and large scale restrictions recently implemented in some big cities have already resulted in millions of people losing their jobs. Traditional markets have no support from the government to implement safety protocols and are subsequently labeled as harmful and unhygienic. Women make up most of these market sellers and buyers. In coastal villages, fish markets have been closed so women are struggling to sell their fish and shells. In turn this economic difficulty has created an increase in domestic violence.

At the same time, people are showing solidarity and building collective action including several initiatives focusing on connecting the needs of urban and rural people. Some villages have rebuilt their food barns in anticipation of a food crisis, while others are monitoring local distribution of government aid packages to combat corruption. Unfortunately, the government has reallocated budget from village empowerment and education to the military and the country is close to martial law since the government believes people will not follow regulations due to their need to sustain their livelihoods.

Moayyad Bsharat of Union of Agricultural Work Committees (UAWC), began by outlining the geopolitical situation. According to the Oslo agreement , the West Bank is divided into areas A, B and C. Area C is under total Israeli administrative and security control and forms more than 63 per cent of the entire West Bank with 95 per cent of productive agricultural land for Palestinian food production and more than 300,000 people living there in marginalized conditions. Despite international law, Israel is failing to take responsibility for the care and health of the people under their occupation. Many vulnerable Palestinians are therefore at increased risk from COVID-19, also considering the lack of accessible hospitals and Israel’s refusal to contain the growing number of infections within Israeli settlements in the West Bank.

Moayyad Bsharat of Union of Agricultural Work Committees (UAWC), began by outlining the geopolitical situation. According to the Oslo agreement , the West Bank is divided into areas A, B and C. Area C is under total Israeli administrative and security control and forms more than 63 per cent of the entire West Bank with 95 per cent of productive agricultural land for Palestinian food production and more than 300,000 people living there in marginalized conditions. Despite international law, Israel is failing to take responsibility for the care and health of the people under their occupation. Many vulnerable Palestinians are therefore at increased risk from COVID-19, also considering the lack of accessible hospitals and Israel’s refusal to contain the growing number of infections within Israeli settlements in the West Bank.

Since 2007, the Gaza strip has been under an Israeli blockade. The population are trapped in terrible conditions with weakening health and increased vulnerability to infection. In addition, the Palestinian Authority’s neoliberal policies of privatization have left small scale farmers and impoverished families unable to cover their primary healthcare.

Since the outbreak, UAWC has been campaigning for farmers and marginalized families who have a lack of healthcare support from Palestinian authorities as well as due to Israeli restrictions and occupation. In a bid to assist farmers in returning to their land to cultivate, UAWC is distributing 350,000 vegetable seedlings in support of nourishing food production that does not depend on the commercial and chemical processes of agribusiness. The organization also supplies herding communities in marginalized areas with hygiene kits to deal with COVID-19.

Moayyad, like Rob, cited the pandemic as the result of capitalism and a basic disregard for humanity and the environment as well as the small scale farmers who are producing the healthy and nourishing food needed during this crisis.

Paula Gioia, a peasant farmer and beekeeper in Germany and a member of the Coordination Committee of the European Coordination Via Campesina, provided a perspective on the situation in Europe.

Paula Gioia, a peasant farmer and beekeeper in Germany and a member of the Coordination Committee of the European Coordination Via Campesina, provided a perspective on the situation in Europe.

Agriculture in Europe has been structured over the past decades on an industrialized model that feeds corporations, labor exploitation, human rights violations, loss of diversity and animal diseases. However, 95 per cent of farms in Europe are small or mid-scale feeding local populations with fresh and healthy food beyond the long supply chains of supermarkets. In times of the pandemic, peasant agriculture continues to be threatened by globalization and international markets including increased difficulty in accessing public peasant markets. In Spain, Italy and France the closure of the food service industry, limitation of direct sales and the increase in the concentration of food trade in large supermarkets represents huge economic losses for small scale farmers. This comes during Easter, a time of year when many small scale meat producers make most of their annual income. The good news is that direct sales through consumer cooperatives, shopping groups, community-supported agriculture and the open-air markets still allowed is proving to be a resilient strategy.

Another consideration is the aging of European farmers. With an average age of 65, the core of the sector is very vulnerable to COVID-19 infection and faces extra difficulties regarding delivering their produce and accessing fields. Field access is also proving difficult in the context of lockdown policies designed for urban areas. In a rural context housing and farms are not always in the same place so many cannot access their place of work. Considering the waged work structure of Western European agriculture, many seasonal migrants already forced to accept poor working standards are now facing dangerous health and safety conditions as well as reduced labor rights due to longer working hours. These are just a few of the developments impacting not only the existence of small scale farmers but also our entire populations right to food and nutrition.

Sai Sam Kham of Metta Foundation in Myanmar,saw many parallels in Myanmar. In the context of likely inaccurate numbers of infected due to limited testing capacity, there has been a panic reaction stemming from a deep-rooted and justified mistrust in the government and its healthcare capacity. As mentioned by other panellists, the social distancing measures and lockdown policies in place are a difficult idea for many people, not only culturally but in the context of wage laborers and much of the rural population now unable to make a living. There is a rise of xenophobia as the large numbers of migrant workers returning from Thailand and China are vilified. The government quarantine plan addresses people returning by air but not via border areas. By the end of March some 75,000 people returned from the Thai-Myanmar border with no capacity for accommodation in quarantine facilities. After a simple temperature check they were sent home and advised to self-isolate but there is no monitoring or regulatory system in place. Despite imposing class blind interventions, the government is also attempting to provide food for those in need. However, there is much public criticism over the organization of this aid.

Sai Sam Kham of Metta Foundation in Myanmar,saw many parallels in Myanmar. In the context of likely inaccurate numbers of infected due to limited testing capacity, there has been a panic reaction stemming from a deep-rooted and justified mistrust in the government and its healthcare capacity. As mentioned by other panellists, the social distancing measures and lockdown policies in place are a difficult idea for many people, not only culturally but in the context of wage laborers and much of the rural population now unable to make a living. There is a rise of xenophobia as the large numbers of migrant workers returning from Thailand and China are vilified. The government quarantine plan addresses people returning by air but not via border areas. By the end of March some 75,000 people returned from the Thai-Myanmar border with no capacity for accommodation in quarantine facilities. After a simple temperature check they were sent home and advised to self-isolate but there is no monitoring or regulatory system in place. Despite imposing class blind interventions, the government is also attempting to provide food for those in need. However, there is much public criticism over the organization of this aid.

The de facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi, is using an official Facebook account to communicate with the public daily, a welcome communications effort, however, more strategic interventions are needed. Hospitals have insufficient PPE gear and medical supplies while much of the population have no access to healthcare. Suu Kyi recently made a plea to the public to be more compassionate to the victims and each other while her government has banned internet access in the conflict-ridden western part of Rakhine and Chin states. People are in need of access to information to fight the pandemic as well as to survive the conflict. Humanitarian aid in many areas is difficult to access and in March alone, more than 100 civilians were killed by indiscriminate air raids and mortar shelling. Over 800,000 vulnerable people are displaced in Rakhine, Kachin, Chin, Shan and Kayin states across the country as well as the one million Rohingya people in the refugee camps of Bangladesh.

Civil society organizations in Myanmar and the general public are trying to do as much as they can. Organizations demand immediate cessation of the conflict while the public are mobilizing to the same effect. China is providing much appreciated medical teams and support, however, their overt strategic economic and political interest in Myanmar is cause for concern of dependency. Sai Sam concluded that conflict, land grabs, dispossession and migration, are all linked to and very important to consider while dealing with this pandemic.

Artist: Elizabeth Niarhos

Artist: Elizabeth Niarhos

Small scale farmers and fishers are heavily involved in acting as agents of historical change not only locally but globally. We may be in a better position now to strike forward against agribusiness and reestablish the story of food in such a way that it is not an industrial economy but rather a part of the natural economy, involving the sun, the soil, the life cycles of animals and the health and welfare of communities. It is fundamental to put small scale farmers and fishers in a position to teach us how to heal this metabolic rift that is dividing ecologies and economies and subsequently driving the worst emergence of pathogens.

This clearly also extends to politics on the national and global stage. A divide between the urban and rural must be repaired in a way that connects the welfare of everyone.

The pandemic has exposed the obvious, that our global health and welfare is connected and the divide between the Global North and South must be addressed. Unequal ecological exchanges in which the North entirely extracts the resources and labor from the South must end. Practices supplied by centers of capital including New York, Hong Kong and London have pushed the development of deforestation that has led to the spillover of these new pathogens.

Panellists and participants identified several ways forward:

The pandemic could be a turning point to show that emerging grassroots initiatives are providing a solution that we already have, our sovereignty. A solution in terms of solidarity, in that knowledge and practices of the people work and therefore agribusiness is unnecessary. If governments carry on with a business as usual approach nothing will change. We need a consolidated movement among the people on the ground to express our demands.

Agroecology is a solution for agribusiness and this should be an opportunity to let people, not only in Palestinian territories but around the world, return to their land to cultivate and prove this. Considering that the neoliberal policies of governments are the main cause of vulnerable communities, they must take responsibility to support small scale farmers and impoverished families. As the slogan of Vía Campesina says we must globalize the struggle. This is a global fight against capitalism and neoliberal policies and a chance for international solidarity to make humanity not profit our priority.

Immediate next steps must be measures from policymakers to guarantee the mobility of small scale food producers to their fields, meadows, waters and markets. In terms of agriculture, Via Campesina demands that all European countries advance the common agricultural policy subsidy payments for 2020 and that small scale food producers who face losses now have tax reductions to be able to guarantee the upcoming sowing and harvest season. The health and safety of these producers and land workers must be guaranteed in the fields as well as at local markets. Longer-term public policies to support new entrants into European agriculture and ensure a generational renewal are also important.

We must finally step down from a model in which large scale animal production, already shown to be far more vulnerable to infections, contributes to climate change and exploiting labor. This is an opportunity for measures to develop local, healthy and sustainable food production in the hands of small scale producers at fair prices.

Concluding the webinar, Rob stressed that what climate change and this pandemic indicate is that we are at a profound historical moment. Our troubled path is largely controlled by sociopaths who believe we can engage in capitalist accumulation as if people are things and can be thrown away as products and there is an infinite supply of resources to burn through without consequence. Somehow we need to break this command of the planet – a huge generational project that will require a total reversal of the present power dynamics. This will extend from immediate tactics under the constraints of how we are operating now to understanding that agribusiness is opposed to public health as a matter of principle and externalizes its costs of production onto animals, crops, local environments, labor and wildlife, all in the name of profit. This must be broken in order for agroecology and regenerative agriculture to reconfigure ecologies back in a way that inputs and outputs speak to each other. If we continue to offload the worst of the damage onto the planet and people we will reach a point where the system will collapse under its own weight, bringing everybody down with it. Can we cycle out of this mode of production to a place where we return to the planet that we walk on? If we alienate the means by which we grow food and produce, we destroy the planet and people on which we depend in order to persist as a species. A profound shift in the very nature of our relationships with each other and the planet is required to be able to address climate change as well as the coming pandemics.