Get in good trouble, necessary trouble, and help redeem the soul of America.— Congressman John Lewis

The crises of 2020—the COVID-19 contagion, systemic racism, and a depressive economic downturn—are testing the mettle of American society. Curiously, they are also expediting efforts to address racial injustice and economic, energy, and environmental inequality within an integrated national climate policy framework.

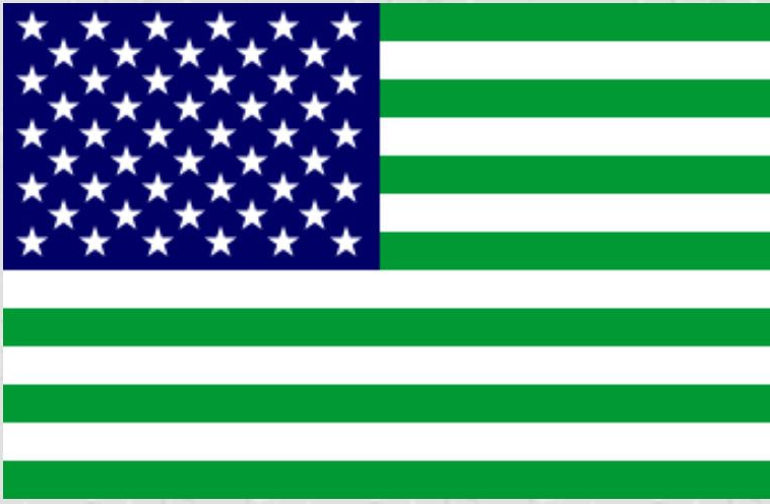

Since the introduction of the Green New Deal (GND) onto the national stage by Representative Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY), the sense of political possibility has been growing. Conceptually the GND goes beyond conventional energy and environmental issues to address underlying social, economic, and racial injustices and inequalities.

The GND concept was roundly ridiculed by congressional Republicans and Democrats alike when it first appeared on Capitol Hill. In less than two years, however, the integrative concept has become a primary policy plank of the Democratic Party and its presumptive presidential candidate—Joe Biden.

Accounting for the rather radical change of approach to solving the climate crisis has been the confluence of events like the record number of billion-dollar weather disasters and the emergence of a novel coronavirus responsible for the COVID-19 contagion. The failure of governments to act in a concerted manner has laid bare the dysfunction of the nation’s political leaders and confirmed for the 99-percent the privileges afforded the one percent.

The death of George Floyd, an African American man, under the knee of a White Minneapolis police officer has triggered a racial justice reckoning the likes of which we haven’t seen since the 1960s[i]. Racial justice has, in many ways, become a metonym for the socio-economic and political inequities that have been ailing America for decades.

The events of recent months have been compared to the civil rights marches of the 1960s. There are, however, significant differences between today’s protests and those of a half-century ago. Protestors taking to the streets in 2020 are more representative of the overall population—racially, economically, and generationally—than the marchers of the 1960s.

Moreover, today’s demands to end systemic racism are more expansive than those of yesterday. In addition to core issues like police brutality, voting rights, healthcare, and economic inequality, for example, are growing calls for energy, environmental, and climate justice.

The 2020 response to the call for an end to systemic racism has prompted the self-evaluation of institutions across society. Organizations of every ilk, e.g., companies, nonprofit advocacy and charitable groups, local governments, et al., are acknowledging their own racism and cultural incongruities —voluntarily vowing to correct them.

The symbols of systemic racism have begun to fall everywhere. Sports teams like the Washington Redskins and the Cleveland Indians are now casting aside the names and logos that, for decades, have disrespected and insulted native Americans. NASCAR has outlawed the reminders of slavery—banning the stars and bars flags of the Confederacy on competitors race cars and within the track venues.

The statues of historical figures like Robert E. Lee, Christopher Columbus, Woodrow Wilson, Roger B. Taney, and others who are known for their racist sentiments or the enslavement of human beings are coming down—at times, peacefully at times not. Serious debates about the characters of George Washington and Winston Churchill are taking place.

Today’s Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement protests are far from symbolic. George Floyd’s killing has become the flashpoint for the center and left-of-center liberal political activists in much the same way Donald Trump ignited right and far-right-of-center conservatives in 2016.

Even before the 2016 elections, strong negative feelings over the inequities of established economic and political governance were building on the left. Hillary Clinton proved to be the wrong candidate to ignite them. Four years of Donald Trump and the continued killing of African Americans at the hands of White policemen have done what Clinton couldn’t.

The coalition around former Vice President Biden of center and left-of-center forces is more of convenience than comfort—again not unlike the grouping that formed around Trump. It remains to be seen if Biden is the man for the times or the beneficiary of them. Should the Democrats capture Congress and the White House, they will need to reconcile the differences between moderates and progressives that were put on hold long enough to defeat Trump and the Republican Senate majority.

Racism may be found at the roots of the environmental movement, within the ranks of the clean energy community, and the oil and gas industries.

Racial and economic injustice and inequality are found in many forms throughout the clean energy and environmental sectors—in its institutions, the siting of polluting industries, and access to technology. Racism has long plagued the environmental movement.

Michael Brune, the executive director of the Sierra Club, has written:

The Sierra Club is a 128-year-old organization with a complex history, some of which has caused significant and immeasurable harm. As defenders of Black life pull down Confederate monuments across the country, we must also take this moment to reexamine our past and our substantial role in perpetuating White supremacy.

Brune is referring to the organization’s founder, John Muir—an overtly avowed racist who had described African Americans as lay-about Sambos. Then there were members and leaders of the organization like Joseph LeConte and David Starr Jordan, who were vocal advocates of White supremacy.

Jordan was a “kingpin” of the pseudo-scientific eugenics movement. He pushed for forced-sterilization laws and programs that deprived tens of thousands of women of their right to bear children—mostly Black, Latinx, Indigenous, and poor women, as well as those living with disabilities and mental illness. Jordan co-founded the Human Betterment Foundation, whose research and model laws were used by Nazi Germany to cull its non-Aryan population.

The Sierra Club has promised to reallocate $5 million from its budget to make more investments in its staff of color and racial justice initiatives, pending board approval.

Racism in environmental advocacy organizations is not just yesterday’s problem. The Washington Post recently reported on the experience of Ruth Tyson, an employee at the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), who quit because she found her job unbearable. In a 17-page open letter to the organization, Tyson wrote about a meeting of a group she was told a majority of her time would be devoted:

…at the convening, although the intention was to uplift voices from “marginalized communities,” the majority of people participating were White. They were working “for” communities of color in some capacity, but not actually representing them. (emphasis added)

Ken Kimmel, UCS president, has read the letter many times and…thought it…fair. He has gone on to say:

I think this is part of a larger issue in all of society, and there is real meaning to the culture of White supremacy. There are ways that a White-dominated workplace doesn’t make it welcoming to persons of color.

UCS and other environmental organizations are hardly alone in their “whiteness.” Looking back over my 40 years in the clean energy and climate fields, it took decades for groups like the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA), American Wind Energy Association (AWEA), and others to integrate. Federal agencies like the Department of Energy (DOE) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) had relatively few African Americans in policymaking or management positions through the 1990s and into the 21st century. Professionals of color were prominent by the infrequency of their presence.

For its initially higher costs and the race of its early adopters, solar has long been considered a technology for wealthy White folks. However, times are changing. New approaches are being found to locate community-solar projects in neighborhoods of color and low-incomes.

The oil and gas industries are much less integrated racially than the US workforce in general. Moreover, the industries are not nearly as committed in practice to hiring African Americans as the American Petroleum Institute would lead people to believe. Inequities in salary compound racism in the sector.

According to Professor Donald Tomaskovic-Devey at the Center for Employment Equity at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Black workers made up only nine percent of the oil and gas industry workforce in 2018. They were paid, on average, 23 percent less than their white counterparts. Similarly, the numbers show substantial underrepresentation in employment and equally lower pay rates for women and Hispanics in the industry.

Following the killing of George Floyd, the CEO of the American Petroleum Institute (API) released a moving statement. Not for the first time, he challenged his industry to drive racism and discrimination out. Actions of the industry, however, speak louder. The fact remains that the industry is a very unwelcoming place for Black, Brown, and female workers. Stories of minority workers leaving the industry for reasons similar to those of Ms. Tyson abound.

The injustice and inequality suffered by minority workers in the oil and gas industry are particularly poignant given that communities of color and low incomes bear a disproportionate burden of the negative environmental consequences that flow from the use of fossil fuels.

The BLM movement is shocking the nation into taking stock of itself and seeing the world through the eyes of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery. In the wake of their murders, environmental and clean energy advocacy groups are vowing to get into good trouble by hiring people of color as equal and valued members of their organizations.

As important as the integration of advocacy organizations is the integration of their policy and political agendas. For too many years, the environmental and civil rights movements have been running on parallel paths. They are at last coming together, and much of the credit belongs to the activism of America’s youth.

Evidence of the merger is found in courtrooms and the halls of legislatures. Novel theory law cases seeking to establish a habitable environment as a constitutionally protected right equal to the right to vote or to an education have been cropping over the past few years. The most prominent of these, Juliana vs. US, was brought by a racially diverse group of young plaintiffs.

Whether or not the constitutional claims of the Juliana plaintiffs are recognized as actionable on the part of the courts, it will ultimately be up to the Congress and the president to craft and enact science-based federal legislation. Legislation that would look conceptually very much like the GND and as described in the report of the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis and put forth by the presumptive Democratic nominee for president, Joe Biden and, vice president, Kamala Harris.

Effective policymaking requires an appreciation of the issues involved. In the case of integrative climate-related policies that seek to redress injustices, as well as to address Earth’s warming, it is necessary to have a clear understanding of the meaning of the terms environmental, energy, and climate justice. Sharing some core characteristics, e.g., limiting access to the policymaking process, the terms are not interchangeable.

This is Part 1 in a series of three articles. Part 2 distinguishes and discusses the differences between energy, environmental, and climate justice. Although sharing many core characteristics, e.g., full participation in the policymaking process, there are important distinctions to be made. Part 3 analyzes the several proposed laws that have been introduced, including the Environmental Justice for All Act, that was introduced into the Senate by Senators Harris (D-CA), Duckworth (D-IL), and Booker (D-NJ). A House version of the Act has been introduced by Representative Raúl M. Grijalva (D-AZ), Chair of the House Natural Resources Committee, and Representative A. Donald McEachin (D-VA).

[i] Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Stokely Carmichael didn’t deserve Bill Clinton’s Swipe during John Lewis funeral, Washington Post.

Lead image: António Martins-Tuválkin