Democracy has a blind spot so enormous that almost nobody notices it – myself included. In the decade I spent as a political scientist researching democratic governance, it simply never occurred to me that we systematically disenfranchise future generations in the same way that women and slaves have been disenfranchised in the past. Yet that is the reality.

They are given no rights, nor (in the vast majority of countries) are there public bodies to represent their interests or potential views on decisions that will undoubtedly affect their lives, from policies to confront the climate crisis and the regulation of artificial intelligence to planning for the next pandemic.

The disturbing truth is that we have colonised the future. Especially in wealthy nations, we treat it is a dumping ground for ecological degradation, technological risk and nuclear waste – as if there is nobody there. And there is little that the unborn citizens of tomorrow can do about it. They cannot throw themselves in front of the King’s horse like a Suffragette, block an Alabama bridge like a civil rights protestor, or go on a Salt March to defy their colonial oppressors like Mahatma Gandhi.

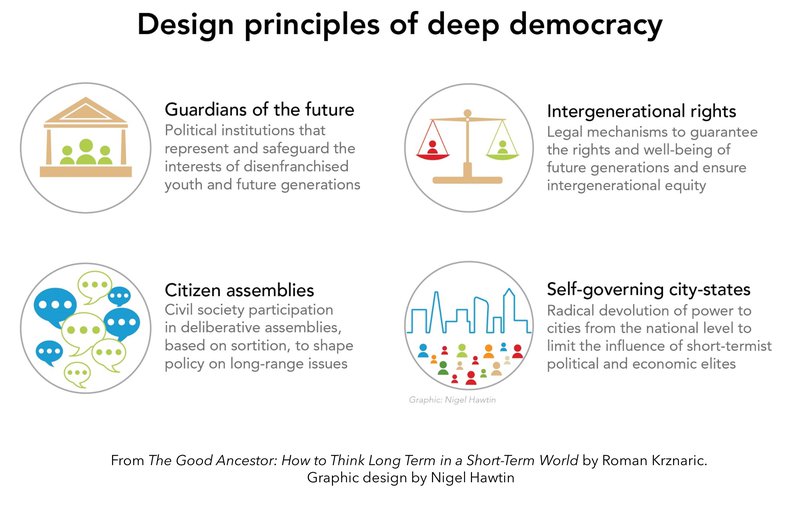

The good news is that a pioneering generation of time rebels is now emerging to challenge the myopic political presentism at the heart of representative government, where politicians can barely see past the next election or even the latest tweet. This vanguard movement of political activists, policymakers and engaged academics has proposed more than 70 different ways to embed long-term thinking and intergenerational justice into democratic institutions, offering a new kind of politics that I call ‘deep democracy.’

Their most powerful and innovative proposals (many of which are already being put into practice) fall into four main areas shown in the graphic below. They don’t represent a blueprint to be imposed on the existing system but rather a set of radical design principles with the potential to inject democratic structures with a far deeper and longer sense of time.

Guardians of the future

Public officials and institutions with the specific remit to represent future citizens who are left out of traditional democratic processes are essential – covering not just children but also unborn generations. One model can be found in Finland, which since 1993 has had a parliamentary ‘Committee for the Future’ comprising 17 MPs who engage in long-term scenario planning around technology, employment and environmental issues.

Wales has taken a different approach, establishing a Commissioner for Future Generations under the 2015 Well-Being for Future Generations Act. Its current holder, Sophie Howe, is a leading time rebel for intergenerational justice who scrutinises public policy for its impacts thirty years into the future, but she has little direct power beyond the capacity to name and shame.

That’s why a new campaign has been launched called Today for Tomorrow to establish a ‘Future Generations Commissioner’ for the whole UK, but with the legal power to hold public bodies to account for failing to act in the interests of future citizens. It’s gaining a surprising amount of cross-party support.

However, such models face a potential problem of democratic legitimacy. Why shouldn’t angry teenage climate strikers have a say themselves rather than having to rely on proxy adult representatives? And how can we ensure that these ‘guardians of the future’ tackle the full range of issues, including the way that racial injustice is transmitted intergenerationally in criminal justice systems?

Citizens’ assemblies

The ancient Athenian model of participatory democracy has been making a comeback in the form of citizens’ assemblies, where randomly selected members of the public deliberate on public issues (a process known as ‘sortition’). In 2016 the Irish parliament established a Citizens’ Assembly that played an historic role in supporting a referendum on abortion. Spain and Belgium now have permanent citizens’ assemblies that feed into municipal government, while in 2019 the UK parliament created Climate Assembly UK to discuss the shift to a net-zero carbon society.

What’s the connection to future generations? Research by political scientist Graham Smith suggests that citizens’ assemblies “outperform traditional democratic institutions in orienting participants to consider long-term implications.” In part, this is because they encourage the ‘slow thinking’ that’s required to engage with long-range issues, but it’s also because ‘sortition’ ensures a wide variety of social perspectives and thereby limits domination by traditional elites.

The Future Design movement in Japan is taking an innovative approach to this model. Local residents are invited to make planning decisions for their town or city but are split into two groups. One group is told that they are citizens from the present, while the second is told to imagine themselves as citizens from 2060, and are even given ceremonial robes to wear to aid their imaginative journey. The latter group typically propose far more radical policies in areas ranging from health care to environmental protection.

The Future Design approach, which is now spreading through local authorities in Japan, has huge potential to be adopted by progressive towns and cities in other countries. In the UK, it could help transform the House of Lords into a democratically-legitimate House of the Future that considers the legacies we leave to future generations.

Intergenerational rights

A third design principle is to embed the rights of future generations into the legal system, especially constitutional law, as a means of ring-fencing their interests and protecting them from the short-termism of incumbent politicians.

It may sound far-fetched to give rights to future citizens who aren’t even here to claim them, but this is already happening. Back in 1993 and acting on behalf of 43 children, environmental lawyer Antonio Oposa won a landmark case in the Philippines which established the right of future generations to a healthy environment.

In the more recent ‘Urgenda’ case in the Netherlands in 2019, the courts drew on the European Convention on Human Rights to rule that the government has a legal duty of care to protect its citizens from the future impacts of climate change by meeting its own stated targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In the US, Our Children’s Trust is pursuing legal cases to secure “the legal right to a safe climate and healthy atmosphere for all present and future generations,” backed by heavyweight figures such as climate scientist James Hansen and economist Joseph Stiglitz.

The challenge is that even if such cases are successful, there is the subsequent problem of enforcement: why would we expect governments to protect the rights of future people if they so manifestly fail to protect the rights of those who are alive today, such as those fighting for indigenous rights or against police violence?

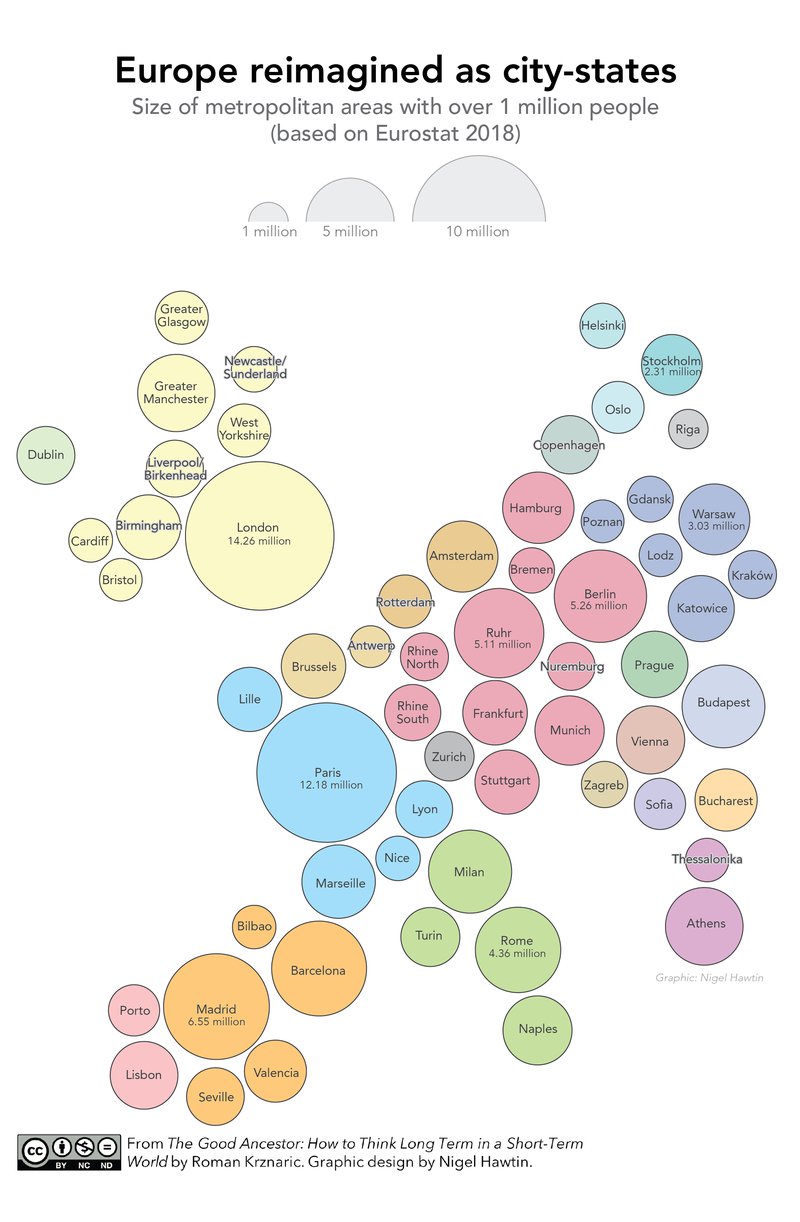

The final strategy for redesigning democracy for future generations is the radical devolution of decision-making power from central government, where it is typically captured by corporations and other vested interests bent on short-term gains. Compelling evidence from a new Intergenerational Solidarity Index reveals that countries with decentralised political systems (such as Switzerland and Japan) perform better on indicators of long-term environmental, social and economic performance.

Devolving power to the city level may be the most effective means of benefiting future generations, because cities have proven themselves to be far better than nation-states at tackling long-term problems such as ecological degradation, migration pressures and housing crises. For example, think back to June 2017 when – just weeks after President Trump withdrew from the Paris Climate Agreement – 279 US mayors representing one in five Americans pledged to uphold the agreement in their own cities such as Boston and Miami.

More recently, Amsterdam has adopted economist Kate Raworth’s model of Doughnut Economics as a way of emerging from the COVID-19 crisis and shifting towards a long-term post-growth regenerative economy. The city is part of the C40 network of over 90 cities that are committed to taking action on climate change.

While nation-states will be with us for some time yet, such interdependent city networks are signalling a gradual return to the era of Renaissance city-states and the Hanseatic League of trading cities in sixteenth-century Europe. Just imagine Europe as a confederation of twenty-first century city-states.

It is wishful thinking to believe that simply voting in politicians who support long-term policies would be enough to secure the interests of future generations. Short-termism is too deeply structured into the DNA of representative democracy. That’s why we need radical institutional change that designs myopia out of the political system.

Democracy itself is under siege from the rise of far-right populism and declining faith in traditional political parties. We should take advantage of the crisis created by the coronavirus pandemic to rethink what democracy looks like in the twenty-first century.

There may be no better way of reviving faith in the democratic ideal than by granting a rightful place to the ‘futureholders’ – the unborn, unknown citizens of the future. It is time to expand the boundaries of the demos forward in time. Or as the philosopher John Dewey put it, “the cure for the ailments of democracy is more democracy.”

Roman Krznaric’s new book is “The Good Ancestor: How to Think Long Term in a Short-Term World,” published by Penguin Random House.

Click here for more information and to order.

Teaser photo credit: Flickr/Dominic Alves. CC BY 2.0.