Going for Gold Public Engagement Coordinator and the founder of Bristol-based start-up grOWN IT, Florence Pardoe, reports on the webinar she hosted as part of #BristolFoodKind. The webinar explored the idea of who owns our food and asked how we can create a system that works for the people who produce our food, and the people who eat it.

“It’s the crux of the matter that we’ve got to not lose our ownership and the right to share seeds, food and the way we farm”, explains Gerald Miles, owner of Caerhys Farm in the opening scenes of In Our Hands: Seeding Change, which was screened online as part of the #BristolFoodKind campaign.

What does this mean? And what role do we as food citizens have to play in ensuring that doesn’t happen?

As someone who has long been passionate about the power of food to heal the numerous social and ecological imbalances in our world, I have spent much time trying to understand the role of the individual in shaping our food system.

How do we take back control and ownership of our food? It’s my belief that before we can change something, we need to understand it. And so, as a follow up to the #BristolFoodKind film screening of In Our Hands, I wanted to explore the ideas of ownership and control, the structure of food systems and the practical actions we can take as citizens.

To start, our webinar explored the context of the challenges we face with a few select fill-in-the-gap facts, beginning to illustrate the precarious and damaging industrialised food system we have found ourselves with:

(You can find the answers at the bottom of this post. We delved into more detail on each of these facts in the webinar, which you can watch back to find out more.)

When we explore these facts, it’s clear there’s a lot going wrong here. It can certainly feel overwhelming when we have something as complex as feeding eight or nine billion people a sustainable, healthy diet to figure out. Before we feel we can play a role as an individual we need to develop an understanding or appreciation as to how it all works. So, we start to delve into ‘food systems thinking’.

To begin with we think of our food system as being made up of Inputs, Activities, People and Outputs. What would this look like for a homegrown potato? Then we think about what this looks like for a bag of oven chips.

It’s a complex picture, with a linear structure. This means there’s basically no recycling of nutrients and resources. Of course, we don’t find linear systems in nature because they are inherently unsustainable. As was mentioned in the film, we have had this system in place for about 80 years and we’ve got somewhere between 20 and 120 years before it completely fails us.

What this representation fails to show us is the size of the role played by different actors in the system; the supermarkets, the seed and fertiliser corporations and their lobbies, as well as the role of governments.

So, we can also think of our food system in terms of Power, Control, Risks and Benefits.

A useful food system shape to explore this is the tree below.

Where does power, control, risk and benefit lie here? Consumers ought to hold some power and control, but do they exercise it? I believe a major problem is the use of the word ‘consumers’; a disempowering and passive word. If we start thinking of ourselves as ‘citizens’ instead, we start realising our power and control.

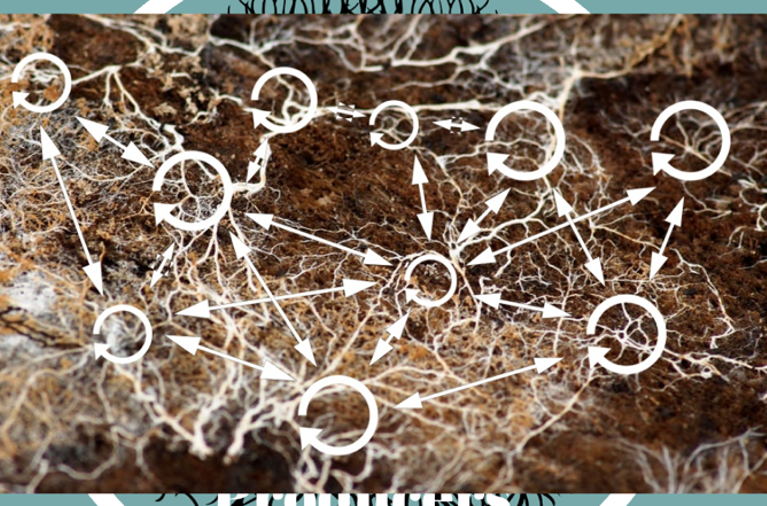

Instead of a tree, we need a food system that looks more like a mycelium network; small, localised and self-governing markets, with lots of interconnections and lot of diversity. Here everyone has choice and the risks and benefits are shared more equally.

A structure like this gives us food sovereignty, a concept introduced in the film.

How do we get there? What role do we play individually? At this point we began to share our ideas as group, which included:

- Community growing projects, allotments, community farms – leading to greater visibility and connection to food.

- Local street markets – more routes to market for producers, more localised and shorter chains.

- Policy and legislation – access to land, incentives and rewards for growing organic, growing to suit your land type, restricting advertising.

- Seed saving and seed sharing.

- Implementation of block chain in food systems giving visibility of source and path.

- Agroecological farming – working in harmony with nature.

- Cooking together – maintaining cooking skills for control over what we eat and to bring people together.

- Education – understanding the problem gives you the power to make informed choices.

- Education in food growing skills and enabling a new generation of farmers.

- Campaigning and active citizenship.

- Changing the language around food.

- Addressing inequality for farmers and the general population, for example providing a Universal basic income.

- More foraging.

- Clearer labelling – standardised and honest.

We then introduced Joy Carey, Going for Gold Coordinator and Consultant in Sustainable Food Systems Planning, and Steph Wetherell, Coordinator of Bristol Food Producers.

In brief, Steph discussed how all areas of action are important, and how we must not underplay the role of policy. She talked about the Agriculture Bill recently passing through parliament and the opportunity it presented.

Joy touched on the move to ‘build back better’ and the importance of our role as food citizens and our ability to influence outcomes through demand. She also gave us an insight to the international momentum on food sustainability that has been growing since the pandemic.

Finally, I put it to our speakers “How do we maintain this change we are seeing?”

Steph put it very well. The pandemic has highlighted problems in our food system, not caused them. There is more discussion about where food comes from now than ever before and people are beginning to recognise the value of food and farmers. We must continue engaging people and enable them to grow their connections with the source of their food and the joy it brings.

I’d like to invite you to visit my website. You’ll find information on what grOWN IT does, resources and ideas to help you engage in a better food system, and links to a host of amazing organisations and campaigns. You can also join our newsletter to keep up to date with relevant campaigns and news.

In the meantime, here are the stats relating to the graphic at the very start of this blog post:

- Nine companies control 94% of grocery supply in the UK, up from 8% in 1969.

- We spend £120bn on food and (non-alcoholic) drink in the UK per year. The externalities created by the system cost an additional £120bn per year.

- 80% of all antibiotics used are fed to animals globally.

- Usually quoted is that 70% of food globally is produced by small farms. In fact, 70% of the world population live off small farms but do not account for 70% of food consumed or produced. The real figure has been estimated as 30-34%.

- Mineral levels in soil have fallen an average of 72% in Europe in 100 years.

- Chicken contains five times less omega 3 than in 1970.

- The UK imports up to 80% of its food.

Finally, I am running two half marathons in July to raise money for the development of grOWN IT and the ongoing work of The Landworkers’ Alliance. If you are able to contribute any amount, no matter how small, it would very gratefully received.

Read Joy Carey’s blog post suggesting five core principles on which to start building a better and more resilient food system. In a follow up to Joy’s blog Sara Venn, Founder of Incredible Edible Bristol reflects on some critical ingredients required to increase urban food production (land, skills, business support, investment, understanding, committed and loyal customers).

#BristolFoodKind is a collaboration between Bristol Green Capital Partnership, Bristol Food Network, Bristol City Council and Resource Futures. See our #BristolFoodKind food waste highlights and grow your own highlights.

Visit Bristol Food Network for more information and resources on Bristol’s Good Food response to the pandemic.