Ed. note: You can find Episodes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 , 8 and 9 on Resilience.org.

The story of Bhagat Singh Thind, and also of Takao Ozawa – Asian immigrants who, in the 1920s, sought to convince the U.S. Supreme Court that they were white in order to gain American citizenship. Thind’s “bargain with white supremacy,” and the deeply revealing results.

John Biewen: Hey everybody. This is John Biewen. I just want to take a second here at the top to say a big thanks to those of you who’ve said nice things to us about our ongoing series, Seeing White. (It is ongoing, this is not a sendoff any kind, I just want to make that clear.) Especially those of you who’ve told your friends, or shouted about the series on social media or on listservs or your blogs or whatever. Thanks, too, if you’ve subscribed to the show or done a rating and review that helps to increase our visibility on iTunes or other podcast apps. The response to the project has been really encouraging. Needless to say, we think everybody should hear the series. We’ve got a number of episodes still to come and I promise, toward the end of Seeing White, we will get to those questions about how to respond, what we collectively should do in the face of what we’re learning here. For now, Seeing White, part ten.

Throughout the series we’ve talked about different ways in which whiteness got made and defined: socially, politically, scientifically. But courts in the United States have sometimes been faced with the question, too: legally, who is “white” and who isn’t? With real stakes, including, who gets to be a U.S. citizen. Remember, our national mythology today talks about a multi-racial, multi-ethnic America, but the Naturalization Act of 1790

declared that citizenship could be granted to, quote, “any alien, being a free white person.” This country’s first Congress said you can come from anywhere in the world and have full citizen’s rights—as long as we see you as white.

Tehama Lopez Bunyasi: But they don’t really decide, well, what does that mean?

John Biewen: This is Tehama Lopez Bunyasi. She’s a political science professor at George Mason University.

Tehama Lopez Bunyasi: So this kind of, rather abstract notion, gets meted out. In the streets but also in the courts.

John Biewen: Back then, the founders of the new United States thought they had a pretty clear idea of who they’d deem white and who they wouldn’t. But when it came to it, local judges had to make the call on who could become a citizen.

Tehama Lopez Bunyasi: The outcomes were rather haphazard. And the arguments, both by the petitioner and then also by, you know, the courts, are all over the place. They change over time.

John Biewen: At the end of the Civil War, the 13th Amendment banned slavery. And at that point, the right to become a naturalized citizen got extended to people of African descent. So now if you were deemed white or black you could become a citizen. The one-drop rule, a holdover from the construction of race designed for the interests of slave owners, clarified the line between white and black.

That’s how it was for the next few decades. But around 1900 we start to see a lot more immigrants to the U.S., many of them not obviously white or black. They see that a key step to building a life in the U.S. is to be a citizen. People did not throng to the border saying, “I’m black, let me in to white supremacist early 20th century America.” The much more desirable path to citizenship was whiteness.

So, you saw more and more people arguing their whiteness before state courts, and more judges making those haphazard rulings on who to let into the club. Congress under Theodore Roosevelt decided it was time to intervene and make whiteness a federal matter. The Naturalization Act of 1906 declared that immigrants must make their case for citizenship before a federal court. If you want to enjoy full rights in the U.S., a federal judge needs to say you’re white.

At this point, I’m gonna turn things over to reporter Audrey Quinn. She produced this episode for us. Audrey tells the story of how the definition of whiteness fell into the hands of the Supreme Court of the United States, in two cases in the 1920s.

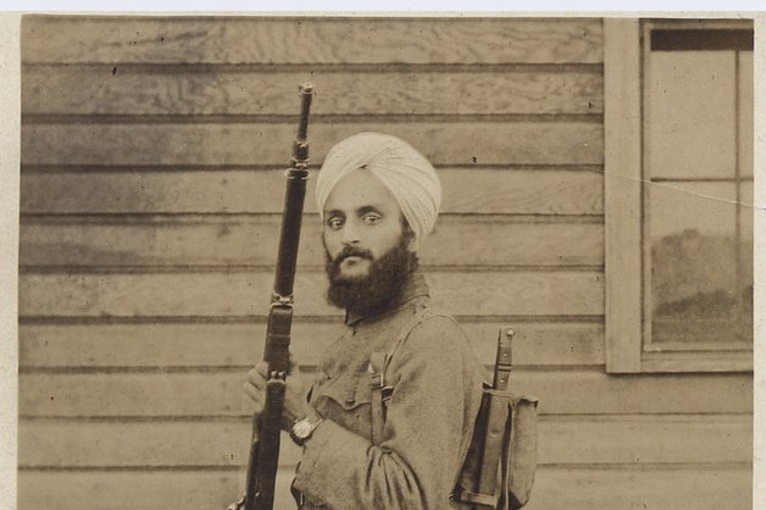

Audrey Quinn: Bhagat Singh Thind was born in 1892 in the Indian state of Punjab. It’s the heart of the country’s Sikh community. His family’s of a prominent caste, his dad’s a spiritual leader. Thind goes to college in India, he’s this budding Sikh philosophy buff. And a move to the U.S. starts feeling like his next obvious option. He had grown up reading Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman, the so-called armchair Orientalists. You have to imagine he figured that if America celebrated men like those, men who aspired after Eastern religions, then it had to be a good place for him. He’s got the real deal Eastern religion. So in 1913 he comes to the U.S. There’s only a couple thousand other East Indian here, but he starts trying to make a life for himself—he finds work, goes to grad school at Berkeley, joins the army. And eventually, Bhagat Singh Thind does become this esteemed religious philosopher in America. And that’s how his son David knew him.

David Thind: He never talked about anything about the Supreme Court case.

Audrey Quinn: Bhagat Singh Thind had a devoted following as a spiritual guru. He was Sikh himself but his sermons were more non-denominational. He gave lectures all over the country. Local newspapers would write about this handsome bearded man in the turban, who filled their auditoriums for weeks straight. David’s mother used to take him to the lectures his father gave—crowds of thousands.

David Thind: Oh, it was wonderful. Everybody loved him, and they listened very attentively to what he had to say. Especially his disciples. And, you know, basically to the letter.

Audrey Quinn: You can tell David really looked up to his dad. Bhagat Singh Thind was gone most of the time. He travelled the country with his preachings almost nine months a year. But David says knowing how much his father meant to other people, that made it okay. And when Bhagat Singh was home with the family in West Hollywood, he was really there.

David Thind: We went on walks almost every afternoon when I was a child. We went to the beach quite often when he was here in the summer. The whole family went down, he loved the ocean.

Audrey Quinn: Did he ever talk about his time in the forestry or in the army?

David Thind: No. He never talked about, I had no idea he was even in the army. You know, he came here, there was no employment here except in the lumber mills, in Washington and Oregon. So he worked for almost 8 years in a town, it’s called Astoria, Oregon, and it was known as Hindu Alley. All this was discovered after I visited three national archives and got the information on his life.

Audrey Quinn: Bhagat Singh Thind died in 1967. And in 2006, David Thind had started writing a book about his father. Like, he already thought he dad was a big deal, lecturing to crowds of thousands and all. But researching the book in those national archives, he also finds a man who had not only withstood years of hard labor, had been the first Sikh to keep his turban and beard in the US Army, but also had been at the center of a case which set out to clarify, once and for all, who was white in America.

Thind first applied for citizenship in Washington State in 1918, wearing his army uniform. He got it, but the court revoked his citizenship four days later when an immigration officer argued that Thind’s not white. Two years later an Oregon judge declares him a citizen again. The same immigration agent objects. This Oregon judge holds his ground in Thind’s favor. The case goes to the Circuit Court of Appeals and then to the Supreme Court. And it’s worth noting here that the main question in the case is not whether it’s okay to have racial restrictions on citizenship. The question stated on the court document reads simply this: “Is a high-caste Hindu,” — this is referring to Thind, Hindu equalled Indian at the time — “Is a high-caste Hindu of full Indian blood …a white person?”

But just before Thind’s case goes to trial in 1923, another case comes up before the Supreme Court—someone else who is arguing to be classified as white. Takao Ozawa is from Japan, but he had been in the US his entire adult life. Like Thind, Ozawa realizes to get ahead in the US, he needs to become a citizen. And also like Thind, he realizes that to do this he needs to prove his whiteness. Here’s Tehama Lopez Bunyasi again.

Tehama Lopez Bunyasi: In his legal brief he talks about how he recognizes the U.S. government and does not recognize the Japanese government. He does not affiliate himself with any kind of Japanese civic groups. He has his kids go to so-called American schools and American churches. He talks about being an English speaker, an American English speaker. And not only teaching his kids English but teaching them monolingually to speak English.

Audrey Quinn: It’s interesting to me just how much erasure there is in his case, of his Japanese heritage.

Tehama Lopez Bunyasi: Assimilating, into this idea of Americanness, really, but really its whiteness in particular, is very much at the heart of his argument, of many people’s arguments. He’s really talking about being a patriot. But he also in his argument says that well if you want to talk about somebody who’s white, well look at the color of my skin. Think about the parts that are typically covered by clothing, that’s rather light.

Audrey Quinn: It’s such a literal argument that he’s making.

Tehama Lopez Bunyasi: It is a literal argument. But I think a literal argument about the lightness of skin color, in many ways, seems to be sort of one register for whiteness, is how light one is.

Audrey Quinn: So what’s the ultimate ruling in the Ozawa case?

Tehama Lopez Bunyasi: The Supreme Court says that, well yes, you’re light skinned, we get that. However, we believe that to be white means to really be Caucasian. And clearly you are not that. And so the ruling kind of takes up the science of the day and says, well, to be white, means to be Caucasian.

Audrey Quinn: And here we get back to Bhagat Singh Thind. Now Thind is no Takao Ozawa, he makes no claims at being a great assimilator, he’s kept his own look, his own religion. But in the Ozawa ruling, that white equals Caucasian, Thind sees an opportunity.

Ian Haney Lopez: Thind was able to rely on what the court had just said months earlier.

Audrey Quinn: This is Ian Haney Lopez, he’s a professor at the UC Berkeley School of Law.

Ian Haney Lopez: He said look, anthropologists classify me as Caucasian, Caucasians are white. Naturalize me. Slam dunk. It seemed an incredibly easy case in the spring of 1923.

Audrey Quinn: Thind is saying hey, I’m literally Caucasian. Like, my people are from the Caucasus mountains. His lawyer adds that not only that, Thind’s people were the conquering people of India, the upper caste, and they are pure. The lawyer doubles down. The argument is, Thind is not only Caucasian, he knows how to look down on his so-called inferiors also. Here’s what Thind’s lawyer put for the closing argument, quote:

“The high-caste Hindu regards the aboriginal Indian Mongoloid in the same manner as the American regards the Negro, speaking from a matrimonial standpoint. The caste system prevails in India to a degree unsurpassed elsewhere. With this caste system prevailing, there was comparatively a small mixture of blood between the different castes.”

David Thind: His lawyer said that?

Audrey Quinn: Yeah.

David Thind: I don’t know anything about that.

Audrey Quinn: This is Bhaghat Singh Thind’s son, David, again. He says the argument doesn’t fit with what he knew of his father. This was a guy who later set up scholarships for poorer Indian immigrants.

David Thind: That doesn’t sound like a very strong argument.

Audrey Quinn: Now, we don’t know whether the lawyer’s arguments reflected how Thind really felt. And the desire to become a citizen and use every possible avenue to get there isn’t necessarily racist. But the arguments that his lawyer uses, heard in 2017, do seem kind of racist. But Matthew Hughey says the argument makes sense if you consider what Thind was dealing with. Hughey’s a sociologist at the University of Connecticut.

Matthew Hughey: I think he was trying to make a bargain with white supremacy. By saying I’m not like the others. I have a culture that is superior and I fit with you also, superior white people. Therefore I should be taken into the fold. If we think about whiteness as a cult, then that’s what he was trying to do, he was applying for membership and, “Bring me in, I’m supposed to be a part. I am pure, I am better, I am great, and I’m gonna only add to the greatness of this nation,” right?

Audrey Quinn: Yeah, I mean, I also have to think that he was doing what he could. Or what he saw as within his means to do to argue his case.

Matthew Hughey: Yeah, I don’t know what else you would have tried to do as a man of Indian descent. I mean he, it looks very methodical and purposeful. I’ve done all these things I’m supposed to do. And I’m appealing to your own white scientists’ views and white philosophers’ views on what race is. And yeah, it is very, very troubling, when we look at the ways he was pathologizing and attributing dysfunction to other groups and other people, but again he was using the logic and the rhetoric of white supremacy to make a claim to join whiteness. And it backfired on him.

Ian Haney Lopez: So the court in Thind’s case said, “You may be Caucasian, we’ll concede that. But we have deep doubts about science.”

Audrey Quinn: Ian Haney Lopez from UC Berkeley School of Law again.

Ian Haney Lopez: And everybody knows a dark brown Hindu is not a white person. And this is really an extraordinary moment. Because here you have the court saying, “Science has in some ways betrayed us because it’s including all sorts of people that we don’t believe are white. So we’re gonna jettison science, and we’re gonna say the only people who are white in terms of being able to join the country are the sorts of people that we as a country believe are white.” And this moment crystallizes that white is really something that’s socially constructed. It’s produced by cultural practices.

Audrey Quinn: Whiteness is what the common man says it is, like what is that saying?

Ian Haney Lopez: This is the significance of the Thind decision. It said we were happy to rely on science when it confirms our prejudice, but when science challenges our prejudice, we’re out. We’re gonna abandon science and continue with a racial project with no scientific justification whatsoever.

Audrey Quinn: Sounds familiar.

Ian Haney Lopez: Yeah. So law helps create and maintain racial oppression. It did so before the advent of any sort of race science, and it did so once race science repudiated the idea that there were biological distinctions between humans that could rank order humanity in terms of superior and inferior groups.

Audrey Quinn: The Supreme Court case didn’t just backfire on Thind. About 50 Indian Americans before him had been successful at getting citizenship. After the Supreme Court’s ruling, they all lost it. They lost land if they owned it, they lose businesses. The women married to them lose their citizenship, too, even the ones deemed white. One prominent Indian American businessman commits suicide. Over a third of all East Indians in America leave the country.

But this cycle of logic that American equals white, and whiteness needs to be protected, it’s not limited to the Ozawa and Thind cases.

Matthew Hughey is the sociologist from the University of Connecticut. He says we see it in the Obama birther controversy, in the immigration debate over Mexican immigrants, and again in a recent Supreme Court case.

Matthew Hughey: So let’s, let’s take a look at the Fisher case.

Audrey Quinn: This is Fisher v. University of Texas, from 2016. Abigail Fisher, a white woman, had applied to the University of Texas at Austin, and she didn’t get in. But she believed worse students than her who were black and Latino were getting in, and taking her spot. So she sued the school for racial discrimination.

Matthew Hughey: Her lawyer said people of color got in who had lower grades than her. And this is an example of anti-white bias, quote-unquote “reverse racism,” and this is an example of why affirmative action is racist against white people, right? And this is what I find remarkable about this case, is that we’re not post-racial, we’re post evidence.

Audrey Quinn: Here’s the evidence. The year Abigail Fisher got rejected, the University of Texas Austin did accept forty-seven students with lower grades and achievement points than her. But only five of those forty-seven students were black or Latino. Forty two of the students who got in with lower scores than her, who took her quote-unquote “spot,” were white.

Matthew Hughey: Her lawyer’s case, I think, makes sense if you don’t think about it, or if you don’t look at the evidence. Because when you look at the evidence, what’s up with those other 42? Well, they were white. They did get in. So the actual evidence shows that there was bias, but it was a pro-white bias. But that doesn’t stop case from going to Supreme Court not once but twice. Behold the power of whiteness.

Audrey Quinn: Hughey says the only way the Court’s decision to even hear the Fisher case makes sense is if you think of enrollment at UT Austin as something white students are entitled to. Only then is it cause for concern that any lower-scoring black and Latino students got in at all over this white woman, regardless of all the white students who also got in over her. It’s like in Thind and Ozawa, where citizenship was considered a de facto white resource. One that’s worth defying logic, or even the court’s own previous ruling, to protect.

Matthew Hughey: So I think the similarities with Ozawa, Thind, and Fisher, right, are similar because they all exhibit the use of a logic that whiteness is somehow under attack, is aggrieved, and needs remedy through the court. And those two cases in 1922 and 1923 were about protecting those resources, very explicitly white resources—political, social resources. The protection of these resources is no different when you look at the Fisher case. Because it’s about educational resources.

Audrey Quinn: In the end, the one thing that Bhagat Singh Thind kept defending was America. He finally got citizenship in 1936 after a new law was passed that gave citizenship to all veterans of World War I. And the fact that he never shared any of this struggle with his son David seems to suggest either it really wasn’t that big of a deal to him, which seems hard to imagine. Or, that it didn’t fit with the image of America that he’d held so closely, that it was a place that would trust and respect him. But regardless of Thind’s battles over citizenship, and whiteness, he never stopped being a believer in the idea of America.

David Thind: My mother and father went back to India 1963 for the first time, and you know travelled all through India, giving lectures on what America means to him. He felt his teachings could be best given here in this country of any place in the world. Because it’s a new country, it’s a receptive country, and it’s a mixed country of all kinds of religions and people.

Audrey Quinn: Two years later, in 1965, Thind was in Tulsa, Oklahoma…Bhagat Singh Thind, 1965 recording: Now we shall all sit straight, hands on theknees….

Audrey Quinn: He’s giving five weeks of lectures in a hotel ballroom, complete with breathing exercises like these, which were said to make you look twenty-five years younger.

A reporter from the Tulsa Tribune interviewed the visitor. She asked him about his return trip to India, and he mentioned to her the caste system there, the caste system that his lawyer had bragged about four decades earlier before the Supreme Court. It seems to be going away, Thind told the reporter. But just like in the U.S., you can’t force the people considered white to care about the darker skinned people overnight. And then he went back to the hotel ballroom, in his turban and beard, and gave another lecture before another crowd of Oklahomans. The lecture was titled, “How to Live Triumphantly on This Earth.”

John Biewen: Audrey Quinn.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: Hello.

John Biewen: Hey Chenjerai, it’s John. How you doing?

Chenjerai Kumanyika: Hey man, how you doing?

John Biewen: I’m doing all right, you?

Chenjerai Kumanyika: Chillin’, man. Just trying to live triumphantly on this earth.

John Biewen: [Laughs.] I think you’re succeeding, I would say.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: That’s good, man. At least somebody does.

John Biewen: He is back. Chenjerai Kumanyika, media scholar, now at the School of Communication and Information at Rutgers University, activist, artist, podcaster. Our conversations are a frequent feature of the Seeing White series, as Chenjerai helps me unpack the stories we’re telling.

One thought I have, Chenjerai, in listening to Audrey’s story about the Thind and Ozawa cases, is the point that you made in one of our conversations in a previous episode, about how recent it is that we as a broad society—that it’s been a mainstream idea, more or less, that we are a multi-racial, multi-ethnic country. And that’s who we are and we’re happy about that. [Laughs] It’s really a, post-Civil Rights Movement, the last 50 years or so, out of a 240-year history of the country. Before that, way into the 20th century, being an American, at least a full-fledged, regular, non-marginal American, meant being white.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: Exactly. Like, this is recent. People act like, you know, the Voting Rights Act got passed in 1777, and like in 1778 Barack got elected. [Biewen laughs.] And you know, come on. Or like 1866, you know what I mean?

John Biewen: Yeah.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: But nah, this was way later, and we’re still arguing about voting rights now. I mean, the voting practices right now of the GOP are explicitly racial. This has been ruled on, determined, by so many courts.

John Biewen: Including here in North Carolina, where I live, where a court now has repeatedly said that the redistricting process was designed with “surgical precision” to minimize the power of black voters.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: That’s right. So yeah, I mean, for a large part of this [country’s history], and I would argue to some extent now, whiteness is a prerequisite for both human and civil rights. And it was offered explicitly to lower-class Europeans and other groups in America, as part of a sort of divisive political project, as we’ve been talking about. And other groups, like Japanese and Indian folks, that have tried to get access to whiteness—they weren’t really offered it but they just astutely recognized what the order of the day was and how they had to position themselves. But even if you had really strong arguments, like Thind did, whiteness could be used, this idea, to say, actually no, we don’t think you should have rights and it doesn’t really matter why.

John Biewen: Right. We just don’t see you as white, plain and simple. You know, and it’s poignant, or I don’t know what the right word is for it—it’s certainly telling—that Bhagat Singh Thind or his lawyer thought that the way to persuade the U.S. Supreme Court to declare him white was to say that he was from a high caste of India, that he was of pure blood, and that, so tellingly, he says, I look down on the quote aboriginal Indian Mongoloid in the same manner as the American regards the negro. Ugh. Where do you even start with that?

Chenjerai Kumanyika: Well, sadly, hearing that reminds me of Gandhi, because apparently in certain parts of his life Gandhi was talking that way, too. But you know, I guess in the long run he got better. But yeah, what’s interesting to me is that Thind, who was living in India under a system that Americans like to separate themselves from, he looked at our system and said—he recognized it. There was a recognition, like, oh yeah this is a caste system, I know what this is. And I know where I am in my caste system so maybe I can, you know, take advantage of that. And so one way to look at that is through the lens of his personal character and it becomes like this moral failing where he was willing to use this racist concept for his personal gain.

But I think it’s, there’s something bigger than that, and it’s about what kind of legal, cultural, and economic system incentivizes you to make that kind of argument. You know, that’s the kind of argument you have to make, in a way. You do have to make that kind of argument in order to achieve, try to strategically and tactically get something like full humanity. Right? You know, you have to become a white man, you have to enter into the only category of personhood that had full rights. And so, and there’s a cost when you use that, though, because you’re reproducing that in legal precedent. And in a lot of ways law is one of the places where things then diffuse into the culture and seem natural and normal and justified. You know, that rhetoric of the law is powerful.

John Biewen: And it says a lot, again, about sort of where we were. This is less than a hundred years ago. And so even going back to that conversation you and I had in, what was it, part four, where we had the Thomas Jefferson stuff and we were sort of having this discussion about what is the more dominant, the true, dominant character of the United States throughout its history. Is it a white supremacist country or a, you know, “all men are created equal” country? And this story is not comforting in that regard, at all. Right? Because here you have a guy, the Supreme Court could have said to him, “Don’t bring those ugly arguments in here.” If this were the Jeffersonian all men are created equal country. But that’s not what they said. They rejected him for entirely other reasons, namely that he wasn’t white, or white enough.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: Yes. It’s like back to our little debate, right? It wasn’t really a debate because I think you weren’t really…. [Laughter]

John Biewen: I wasn’t necessarily pushing back too hard against you.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: You weren’t this sort of raving, foaming patriot.

John Biewen: I should have, you know. It would have been more fun maybe, if I’d … anyway.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: Yeah. But I mean it’s like, you know, so it’s back to our conversation about the character of America. And as I said before, I think nations, I think that the idea of a national character, no matter what you say it is, is a fiction.

John Biewen: Yeah.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: I don’t think nations have characters. Nations are so complex. Hundreds of millions of people, different cultures, it’s like to say that the nation has a character is always a political project that we should be suspicious of.

John Biewen: Oh, come on. Indulge me in my conversation about what is the national character….

Chenjerai Kumanyika: Naw! I mean I’m sayin’….

John Biewen: No no no, I’m kidding.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: I mean, but if people want to go there—while I think that the idea of a national character is not really something that can withstand scrutiny, it’s, that’s a dominant narrative in our country, in this country. It’s like, it’s there all the time, we have a certain national character, it’s good, it’s present, so it’s a real thing. And my thing is like, a lot of people who really feel that maybe should come over to my side. Because you know, I feel like America doesn’t really have a character. But then you see evidence like this, it’s kinda like, mmm, maybe it does.

[Biewen laughs.] It’s pretty persuasive.

John Biewen: And another theme that we have talked about at several points in the project, too, is this shifting nature of whiteness, and its arbitrariness. In this case, you had the highest court in the land choosing to define whiteness in a way that brought the result that the justices were looking for, right? In both cases. So you accept what the racial science of the time says when it helps you exclude the Japanese man from citizenship, the idea that being white means being Caucasian, and you reject that same science when you want to exclude the guy from India. And you know, a lot of people are familiar with the idea that, that the definition of whiteness has evolved over time, as well. Not just, you know, one year apart [laughing], in the case of those two Supreme Court

cases, but over decades, and the idea that certain ethnicities weren’t considered white at one time and later got admitted to the club—Italians, Slavs, Jews, and famously the Irish. By the way, one of my grandmothers was Irish. But when I interviewed Nell Irvin Painter, the historian, she made a very interesting point about this idea that I think a lot of people would be interested in. She disagrees with the guy who wrote How the Irish Became White, Noel Ignatiev….

Chenjerai Kumanyika: Because he, his argument is, the Irish weren’t white, and over time through a variety of processes they gained access to whiteness and became white.

John Biewen: That’s implied in the title, right? That they became white. And Dr. Painter says, no, the Irish were always white. And so were Jews and these other groups that I’ve mentioned. They were just, in that time, in say early 20th century America, they were just the wrong kind of white. She says that it really, this kind of what she calls a toggle switch, or the whiteness toggle switch, where you’re either fully white or you’re not, that came later. But in the early 20th century people didn’t think of it that way. They talked about the Jewish race, for example, and anti-Semites said nasty things about the Jewish race. But that was not the same as saying that Jews aren’t white.

And she says, she makes I think a very powerful argument for this. And I think you’ll like this, Chenj, because of how you have, from the start, you want us to focus on power dynamics and who gets rights and resources, not just, you know, how people feel and think about things. And Nell Painter says if you want to know who was white at any given time, look at who got to vote—at least the men, right, before women got the vote. Irish people were looked down on, sometimes viciously, by white Anglo-Saxon Protestants, but the Irish sure as hell got to vote. Unlike some other people we could mention who were really considered not white and were completely excluded from the political process in large parts of the country. And so, because the Irish had that power, she says, before long they were able to get patronage jobs such as the stereotypical Irish cop, you know, in New York or Boston, and before much longer you got the stereotypical Irish politician. And of course now everybody wants to claim their one-sixteenth Irishness and wear green on St. Paddy’s Day. But, you know, that path was not available to the people who were truly not considered white a hundred years ago, and more, especially of course black people.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: Absolutely. And that’s a really good point that you’re calling attention to. Because I think that when you look at the early years of this country, and even you know the early 20th century, there’s a tendency to conflate all of the different oppressed kinds of folks together. Right, as people who just didn’t—because really, for the majority this country, as we said, most people didn’t really have access, the majority of people didn’t have access to the full kind of human and civil rights. So you can conflate them. But it is important to talk about these differences, and how folks were offered particular incentives and particular opportunities. And it’s really, it’s just so hard to quantify the effect of that. What is the effect of those people not being able to participate in the political process and shape the laws? What is the overall cumulative effect of—not just the wealth loss. People talk about the lack of being able to, to lose wealth or not maximize wealth. I’m talking about just the economic survival, right? And how that functions, what that does to people. So it’s just really the impact of that over the, over a long time. I mean, in a way it takes you back to Thind and Ozawa. You understand why they were trying to go through these maneuvers and these changes.

John Biewen: I mean it just says so much, right, that somebody comes from another country and kind of, as you said, sort of looks around and says, “Okay, I get how this works here. You definitely want to be white in this country.”

Chenjerai Kumanyika: What’s so weird is, people coming into the country looking and going “Okay, there’s a club I got to get into.” Right?

John Biewen: Yeah. Or a cult. As that one scholar put it. [Laughter] When I heard that I thought, wow, whiteness is now a cult!

Chenjerai Kumanyika: It’s a cult! I said technology, I think that’s more benign.

John Biewen: [Laughing.] Yeah. I think I’ll take that one, take that option.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: [Laughing.] But you know, yeah, people are like, I want to get into this. And the people who already are in see themselves as individuals, because—and really, I think that you have really pointed this out and it helped me to understand this more clearly, the way in which being an individual is one of the key components of whiteness. Right? Of white subjectivity. Is that too big of a word?

John Biewen: No, no. You can do big words here.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: It’s like, the experience of living as white is a lot about being an individual. And to even be lumped into the group, that’s, I think that’s part of why when you call someone white, part of the injury is not just that whiteness is understood to be evil, exploitative, whatever, but also just like, Are you putting me in a group? I’m not part of a group! I’m me, I’m an individual, you know.

John Biewen: Exactly.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: It’s interesting. So the people who have whiteness, they’re like individuals. Other people look at it and go, oh I got to get into that club, you know. So I can be, so I can be a full human.

John Biewen: Dr. Chenjerai Kumanyika. The editor of our Seeing White series is Ms. Loretta Williams. Stay tuned. Next episode, a personal story: that time I got held up at knifepoint by a teenager in Philadelphia. Whiteness and blackness, danger and violence, the myths and realities.

Music this time by Sometimes Why, Kevin MacCleod, Lee Rosevere, and Blue Dot Sessions. Our website is sceneonradio.org. Scene on Radio comes to you from CDS, the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University.

Teaser Photo credit: Bhagat Singh Thind in U.S. Army uniform. Smithsonian Institution