Ed. note: Parts 1 and 2 of Seeing White can be found on Resilience.org here and here.

Chattel slavery in the United States, with its distinctive – and strikingly cruel – laws and structures, took shape over many decades in colonial America. The innovations that built American slavery are inseparable from the construction of Whiteness as we know it today. By John Biewen, with guest Chenjerai Kumanyika.

Key sources for this episode:

Ibram Kendi, Stamped from the Beginning

Nell Irvin Painter, The History of White People

Transcript:

Mammy: Oh naw, Miss Scarlett, come on, be good and eat just a little.

Scarlett: No! I’m going to have a good time today.

John Biewen: We Americans are notorious for not knowing or caring about history. It’s a generalization, forgive me, history buffs. But it’s a fair one, isn’t it? On the whole, Americans care a whole lot more about tomorrow. Forget yesterday. Yesterday was so long ago, for one thing. Get over it.

Kizzy, reading: For God giveth to a man who is good in his sight wisdom… [door opens]

Master: Is that you reading, Kizzy?

White woman, laughing: Uncle William, it was only a trick!

John Biewen: That said, most of us do have a general picture in our minds of American slavery. Our schools teach it. And the Antebellum South has made recurring appearances in massively popular novels, movies, and TV series.

Father: But don’t split up the family, Master. You ain’t never been that kind of man. Please, Master!

Master: Mr. Tom Moore owns Kizzy now. Mr. Odell will take her away today.

Mother: Oh God, my baby…

John Biewen: Some portrayals of American chattel slavery have been more unvarnished than others.

Platt: But I’ve no understanding of the written text…

Mistress Epps: Don’t trouble yourself with it. Same as the rest, Master brought you here to work, that’s all. Any more will earn you a hundred lashes.

John Biewen: But unless you’ve really gone out of your way to duck the reality of it, you know. Still, how often do we actually let it sink in, how recent it was, and how monstrous? The people who called themselves white, people who looked like me, claimed the right to own the people they called black, to buy and sell and confine them like livestock. Well, no, not like livestock, as livestock. Asserting utter dominance over them, and their children, generation after generation after generation. And they met the unending and inevitable resistance from those enslaved human beings with waves and waves of violence.

Solomon Northup: Goddamn it! Sooner or later, somewhere in the course of eternal justice, thou shalt answer for this sin.

John Biewen: That brutal society did not just spring from the Southern soil. It wasn’t imported either, not as a complete system. The standard American explanation is to say, well, it was the times. It was in the air. The Brits brought it with them. All kinds of people enslaved all kinds of people forever, nothing special here. As we heard in the last episode, there’s a good bit of truth to that argument. In our hemisphere, Spanish colonists practiced a kind of chattel slavery in South America before the English colonists introduced it in the north.

But “our peculiar institution,” as white Southerners charmingly referred to their brand of slavery, was made in what would become the United States. Its totalitarian framework, based on rigid notions of race and sex, was constructed on this continent plank by plank. That process started not too long after the first African people landed in Jamestown on a Dutch ship in 1619, about twenty people stolen from Angola. But the project took decades to complete.

I’m John Biewen, it’s Scene on Radio. This is Part Three of our series, Seeing White. Looking at whiteness, past and present – who made it, how it works, what it’s for. In episode two, we explored the ancient world, back before anybody thought up race as we know it, and the early development of racist ideas in Europe. This time, how race laws and structures took their distinctive and shockingly cruel forms in colonial America. As we’ll see, the innovations that built slavery American style are inseparable from the construction of whiteness as we know it today.

Suzanne Plihcik: And if we know how we made it, if we know how it was constructed, then we have a better opportunity to deconstruct, to unmake.

John Biewen: Suzanne Plihcik again, of the Racial Equity Institute, leading that anti-racism workshop for adult professionals in Charlotte.

Suzanne Plihcik: Let me ask you. When people began to immigrate to this hemisphere from Europe and from Africa in the 1400s, 1500s, and early 1600s, did they come identified by race? No. What was a likelier identification? [voices] Religion, a little later in that period, but first of all would have been – [voices] country of origin. So, your nationality. You came as an Englishman or a Dutchman or an African.

John Biewen: Suzanne says, whatever ideas were floating around in early colonial society about African and European people, there were no official distinctions. Some Africans were free, some were indentured servants, same as the English colonists. Historians say indentured servants from Europe outnumbered those from Africa in the colonies until the later 1600s. It took a bunch of steps to get from those relatively loose beginnings all the way to hardcore chattel slavery confining only people of African descent. How did it happen? We’re gonna look at some the key steps through a few noteworthy and revealing stories.

Story One: Punch, the one who tried to get away.

Suzanne Plihcik: In the colony of Virginia, in 1640, an African indentured servant by the name of John Punch runs away from his servitude. John has figured out that this wasn’t what he imagined it to be. Interestingly, John doesn’t run away alone. He runs away with a Dutchman and a Scotsman. They are all indentured servants; they are all living in identical circumstance. So they band together and run away.

John Biewen: This does not go well. The three men are chased down and caught.

Suzanne Plihcik: And a very interesting thing is recorded in the Colony of Virginia. The Dutchman and Scotsman are given four additional years of servitude as punishment – one to the master to whom they’re indentured and three to the colony. But the African is given what we see codified for the first time as perpetual servitude.

John Biewen: The judge tells John Punch that unlike the two men from Europe, he will labor for his master for the rest of his days.

Suzanne Plihcik: What have we rewritten down? Slavery. Slavery.

John Biewen: Some Africans were already effectively enslaved in Virginia by 1640. But the Punch case seems to be the first explicit approval of lifelong servitude—and the first time African and European people were treated differently in the law.

Suzanne Plihcik: Why was it done?

John Biewen: This is important. Suzanne says whether the judge consciously intended this or not, his decision was a gift to rich landowners.

Suzanne Plihcik: The story of race, folks, is the story of labor. They needed a consistent, reliable labor force. And they could not have a consistent, reliable labor force if that labor force was banding together and challenging the authority of the colony.

John Biewen: Colonial America was deeply unequal. Most people of every color were poor laborers – farm workers, builders, seamstresses. And those workers were prone to getting restless and pulling out the pitchforks. There were lots of worker uprisings. The disparate sentencing of John Punch was one of the first examples, Plihcik says, of what would become an ongoing practice by the rich landowning class and their political representatives: The practice of giving the poor people who looked like those in power, people of European descent, advantages—usually small advantages—over Africans and Native people.

Suzanne: And what did that do? It switched their allegiance from the people in their same circumstance to the people at the top. It eventually created a multi-class coalition of people who would later come to be called white. It created a multi-class coalition. So this was a divide and conquer strategy. It was completely brilliant.

John Biewen: Story Two: Key, the one who got away.

Ibram Kendi: Sure. So, Elizabeth Key was the daughter of a white legislator in Virginia and an unnamed African woman, so she was biracial.

John Biewen: Historian Ibram Kendi of the University of Florida, author of Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America. Elizabeth Key was born in 1630. Her mother, an African, was effectively enslaved. Her father was not only a free white man but a member of the Virginia legislative assembly, the House of Burgesses.

Ibram Kendi: Before his death, her father, her white father, basically asked her slave owner to free her when she became 15. He did not do that. Eventually, she wed an indentured servant who also happened to have some law training in England. They sued for her freedom on the basis that her father was free and also because by then, in the mid-1600s, she had become Christian. And in English common law, you cannot, the paternity or the status of a child derives from the father. And it was also against English common law to enslave a Christian.

John Biewen: So, Elizabeth Key sued on the grounds that she was her English father’s daughter and that she was a Christian. The colonial court ruled in her favor in 1655 and she was freed. Clearly this frustrated the ruling elite.

Ibram Kendi: So by the 1660s, Virginia had changed their laws to basically state that the status of a child was derived from the mother.

John Biewen: That is, the child of a negro woman would be free if the mother was free and a slave if the mother was a slave.

Ibram Kendi: And that a Christian slave basically would not have to become free.

John Biewen, to Kendi: So that closed a, closed a loophole.

Ibram Kendi: Precisely.

John Biewen: Some slave owners had resisted exposing their African slaves to Christianity so long as English law required them to free Christians. The new law explicitly stated that slaveholders could offer “the blessed sacrament of baptism” without fear of having to free the enslaved people who partook of it.

These legal changes, of course, expanded the pool of people who could be permanently enslaved: Christians of African descent, and the children fathered by slave-owning men through the rape of the women they held as slaves. These laws enhanced the bottom line for slave owners. But that’s not all that the white men in charge did to advantage themselves.

Ibram Kendi: Then they simultaneously passed laws stating that white women could not have biracial, have relations with enslaved or even Native American men. So it then gave white men the ability to basically have intercourse with everyone, but then white women and non-white men could not.

John Biewen: Story Three: the lawmakers.

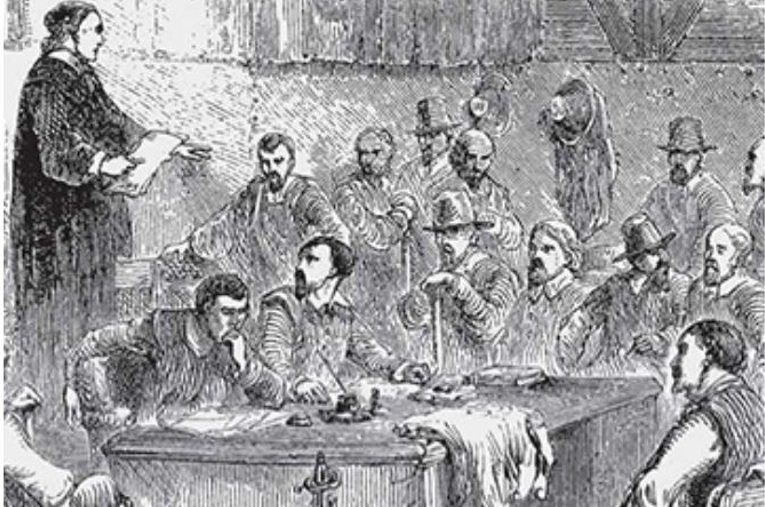

Suzanne Plihcik: By 1680 the Virginia House of Burgesses is literally debating what is a white man. Why are we debating what is a white man? What are we giving away? Land. And rights. We’re basically deciding who is going to be the citizen of this new world.

John Biewen: The Virginia House of Burgesses was the first legislative body in colonial America. In 1682, the Burgesses passed a law limiting citizenship to Europeans. It made all non-Europeans – “Negroes, Moors, Mollatoes, and Indians,” as the law put it – quote, “slaves to all intents and purposes.” Virginia was giving away land at the time, in 50-acre allotments, but only to Europeans.

Nine years later, in 1691, the Burgesses passed another law. According to historian Terrance MacMullan, this law included the first documented use in the English-speaking colonies of the word “white” – as opposed to English, European, or Christian – to describe the people considered full citizens. That is, the people who got to remain citizens so long as they didn’t marry outside of their so-called race. The law read, quote: “Whatsoever English or other white man or woman, being free, shall intermarry with a negro, mullato, or Indian man or woman, bond or free, shall within three months after marriage be banished and removed from this dominion forever.”

Suzanne Plihcik: So, by 1691, we have a definition of white and we have constructed race in what becomes the United States. It’s important that we see this creation was for the upliftment of white people, primarily to support the white people at the top. Poor and working class whites will get little. They will get just as much as is needed to ensure their allegiance.

John Biewen: Story Four: Deciding who counts.

Suzanne Plicik: So we are going to skip ahead a hundred years. It is now 1790.

John Biewen: 1790, the year in which the almost new United States of America conducted its first national census.

Nell Irvin Painter: Yeah, 1790.

John Biewen: Here’s Nell Irvin Painter, who we heard from a lot in the last episode. She’s the Princeton history professor emerita and author of The History of White People.

Nell Irvin Painter: So, the U.S. Census is an instrument of government and it’s meant to sort out the population for purposes of governing. It’s not meant as a scientific classification to sort of float above any policy or material questions. It really, it’s an instrument to be applied. So, let’s count up people in terms that are useful.

John Biewen: And for the U.S. government of 1790, doing its census under the direction of the Secretary of State, a slave owner by the name of Thomas Jefferson:

Nell Irvin Painter: We have three kinds of white people, and then we have slaves and then we have other free people.

John Biewen: To spell that out a bit more, the first U.S. census counted people in these categories: white males 16 years and older, white males under 16, white females, all other free persons, and slaves. Remember, enslaved people were counted as 3/5 of a person for purposes of taxation and representation in Congress.

John Biewen: And were they assumed to be black?

Nell Irvin Painter: I don’t know. I would assume so, but I don’t know. What I do note is that “free” is added to “white.” It’s not that white by itself means free.

John Biewen: Right. So that suggests that there were unfree white people.

Nell Irvin Painter: Exactly.

John Biewen: So, the U.S. government does not choose to count black people, except as part of other categories – slaves and, presumably, “other free persons.” Nor does it count Native Americans.

John Biewen: It also effectively, does it not, defines an American citizen as a white person.

Nell Irvin Painter: That comes more clearly with the Naturalization Act of 1790, which says that the only people who can be naturalized are white, and they use the word “white.”

Deena Hayes-Greene: 1790, we’re seating our first Congress. In the first session, the second act is the Naturalization Act…

John Biewen: Deena Hayes-Greene is Managing Director of the Racial Equity Institute – she works with Suzanne Plihcik and heads up the REI team. At that same workshop in Charlotte, Hayes-Greene picked up the story of the making of race in the U.S. by talking about the next thing Congress authorized after that first census.

Deena Hayes-Greene: The Naturalization Act says only free whites can be naturalized as citizens. What were rights of citizenship in the United States? Hmm? Voting. Land owning. Access and rights to due process. Being able to start a business, sit on a jury. So what we’re saying here, this is the first time that you’re going to see a race, you’re going to see white, written into the documents that speak to our national identity.

We talk a lot about, you know, race has just been around for a long time. Slavery and oppression have been around for a long time. Our record of history, I think we can point to that being around. But we can see specifically that race, the way it’s been institutionalized in the United States, we have a very specific place in our history and in our country where race is showing up as an identity.

John Biewen: In all these ways, over more than a century, the men who shaped the United States defined it as a country by and for the people they labeled white. And they tried to draw hard boundaries, to wall off white. Another big boulder in that wall was the insistence that most mixed-race people with African ancestry be defined as black. The infamous one-drop rule didn’t become law until the early 20th century. But much earlier, states limited the amount of African ancestry a person could have and still be considered white – typically one-fourth or one-eighth.

Ibram Kendi: Yeah, because they were trying to connect blackness to slavery in order to justify slavery, and whiteness to freedom in order to justify white freedom. And so biracial, free people I think would have devastated those racist constructions.

John Biewen: These rules were all about who was on top, and on the bottom; who got land and who didn’t; who got to vote and hold office; who was permitted to marry or have sex with whom; and who could own whom. Suzanne Plihcik and her colleagues with the Racial Equity Institute say, knowing this history, it’s easier to see with clarity what racism is. They define it as social and institutional power, plus race prejudice. Or, put even more simply: A system of advantage, based on race.

Suzanne Plihcik: It is all about power. It revolves on power. It is not prejudice, it is not racial prejudice, it is not bigotry. It is power.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: Hello

John Biewen: Hey Chenjerai, it’s John.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: Hey John, what’s going on, how you doing, man.

John Biewen: So, how about that, at the end of the piece, Suzanne Plihcik saying it’s not bigotry, it’s power. That’s what you’ve been trying to tell me.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: I’m saying, man! That’s what I been saying! [Biewen laughing.] You know what I mean?

John Biewen: That is what you’ve been saying.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: It’s nice to hear somebody else say it. You know, it ain’t like I invented it.

John Biewen: I know. But it’s been a point of emphasis. So…

John Biewen: I called up Chenjerai Kumanyika again. He’s a Communications and Media Studies professor at Clemson University. He’s an organizer, journalist, and artist, and he’s helping me throughout the Seeing White series—to flesh out what we’re discovering, and to give me backup, to help me with any blind spots I may have as a white guy trying to see whiteness. To help us fish who’ve been taught to see ourselves as white to see the ocean of whiteness we’re swimming in.

John Biewen: So much of this, again, was new to me. I put myself in the category of Americans who – ugh, I don’t know that much history, I gotta tell you…

John Biewen: I tell Chenjerai how eye-opening it was for me to learn about the step-by-step creation of American slavery, and of whiteness, in colonial times.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: That’s why I think it’s so important, the story that you all are telling, the pieces of it. And you know another really important piece that I always think of is the Virginia Slave Codes.

John Biewen: And that’s, what, 1705?

Chenjerai Kumanyika: Right. The Virginia Slave Codes happened in 1705. And I think, you know, they intensify slavery and give more rights to slave owners and really to white people in certain ways. But what happens shortly before the Virginia Slave Codes is Bacon’s Rebellion. And by the way, I’m not an expert on any of this either, right. But what we know about Bacon’s Rebellion is that you basically had like these farmers of multiple classes, but a lot of poor folks, [and] you had poor black servants and slaves who were promised freedom if they fought with Bacon. And he was rising up against Governor Berkeley for a variety of reasons, but it seems like the main reason was Bacon wanted to have the right to go and really attack and make war on Indians. You know, and to even use some other Indian tribes to attack other Indian nations.

John Biewen: And this was back in the 1670’s, I believe?

Chenjerai Kumanyika: Right. Bacon’s Rebellion happened between 1676 and 1677, is usually the time frame people talk about. And I want to be clear. Bacon’s Rebellion isn’t really something that we want to celebrate because of the way that it was a part of the genocide of Native Americans. But what it showed the House of Burgesses and what it showed Governor Berkeley was, a multi-racial rebellion that showed the possibility of class solidarity across racial lines. And that was horrifying. And so it was Bacon’s Rebellion itself and things like Bacon’s Rebellion that eventually lead to the Virginia Slave Codes.

John Biewen: So are you suggesting that the Virginia Slave Codes, which were really essentially a vicious crackdown on black people and a real tightening of the screws as far as slavery in the colonies, that that was, in part at least, a way of breaking what could otherwise have been a multiracial coalition of people sort of at the bottom of society rising up?

Chenjerai Kumanyika: That’s right. I mean I think, you know, the story that you all have already been telling involves like this slow intensification of slavery. And I think the Virginia Slave Codes mark a crucial turning point. I mean you just have to look at what’s going on with those laws. I mean, one thing is in Section 34 I think, you get this thing that says when a slave is resisting his master, the master has the right to correct the slave. And if the slave is killed in that process of what they call correction, right, then it wouldn’t be counted as a felony. You know, and it says actually the master, owner and every other such person giving correction ‘shall be free and acquitted of all punishment and accusation.’ So, now you just have the ability of slave holders to just torture black slaves with like, with impunity, basically, and know that they’re not going to face any punishment.

So if you look at part 23 of the Slave Act, it was also, it was encouraging, encouraged white free people to hunt down and capture escaped slaves. And there was this whole reward system that involved tobacco and rewarding people with tobacco so you’re now incentivizing free whites to try to capture free black folks. And there’s also this part that deals with marriage. So any white man or woman who marries a person of African or Indian descent is now going to be committed to jail for a period of six months without bail and has to pay 10 pounds as a fine. So, what you really can see there is like, you can really see the intensification of any racial division really happening there through these laws. Right?

John Biewen: And there wouldn’t have been any need for these laws if people weren’t actually having a tendency to join together, whether it’s in marriage, in relationships, or potentially on grounds of class interest and things like that.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: Right. I mean you look at, in your story, John Punch escapes together with some folks who would now be classified as white. Right? And then you had interracial relations. I mean, people don’t make laws about things that aren’t happening, you know, to stop things from happening if they’re not happening. Unless it’s voter fraud or something like that, then people make all kinds of laws. [Biewen laughs.] But that’s why we have to break this idea that somehow just because of these differences, that the differences were the thing that dictated how people acted politically. People acted politically based on the fact that, you know, in many cases they were sharing some conditions of servitude. And these slave laws, it was a legal project that intensified the division between those and sort of forged that allegiance.

John Biewen: So, a lot of this, a lot of these efforts, the laws, the ways of really forcibly separating the races and setting them against one another, really, and creating only incentives for them to separate—the argument is that those things were designed to lead to what Suzanne called a multiclass coalition of white people, right? As opposed to a multiracial coalition of people who had economic interests in common.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: That’s right. And I mean, one of the most clear expressions of this? My friend Corey Robin reminded me that John C. Calhoun, who was a political theorist, sort of political thinker and statesman from South Carolina who eventually goes on to become vice president, in 1848 he makes, he delivered a speech on this called the speech on the Oregon Bill. And he has this interesting comment in there where he says, ‘With us, the two great divisions of society are not the rich and the poor, but white and black. And all the former, the poor as well as the rich, belong to the upper class and are respected and treated as equals.’ Which is like kind of crazy that he says that, right? I mean, but the first thing to look at, right, is he—the reason why he says the two great divisions of society are not the rich and poor is because he realizes that there are folks who are starting to see it that way, mainly because he’s like a rich-ass plantation owner, you know, who eventually sort of bequeaths land that becomes Clemson University. But, so he has to clarify, he has to jump in and say, no it’s not rich and poor, it’s white and black, and all, all of the poor white people, you have as many rights as me. Which is, of course, not true. But it just shows you like how clear that project was in his mind.

John Biewen: Right. You couldn’t get a more explicit expression of the argument than that, of the divide and conquer argument.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: Right. So you could see that it’s like over a hundred years later, right? But this is this is the project now much more evolved.

John Biewen: And to come back to the big theme of the project: whiteness. There’s a tendency to think that human beings looked around at some point in the distant past and said, well, let’s see, there’s some of us who look this way and then those people over there look that other way, and those people over there look that other way, so I’ll just describe us as, you know, black, white, yellow, red. But this history on this continent shows something so different, which is that it was constructed with very specific purposes in mind, lines drawn around the definition. And it really alters how you see the meaning of black and white, doesn’t it?

Chenjerai Kumanyika: And I’ve got to say, there’s kind of like good news and bad news on that note, you know. The good news is, it really, when you think of this thing called whiteness, there’s not anything genetic that you really share with folks that’s different from what we all share with each other. So there’s a message in here about our connectedness. But the bad news is that, in a way, the effort to get people to come together under the banner of whiteness has sort of always been about power and exploitation. So I don’t know what that means about trying to salvage the idea of like good whiteness. You know, that’s something that you’ve got to wrestle with.

John Biewen: Right.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: You know, when was whiteness good? It’s kind of like, when was America great? I mean, it seems like the whole project was related to exploitation. And so, if you identify that way, yeah. I don’t envy you in terms of having to try to think about what that means.

John Biewen: I’m gonna just leave that there for now. I’d guess we’ll come back to that more personal conversation.

A preview of the next episode in just a second. I want to thank all of you who gave us ratings and reviews on iTunes recently – they mean a lot and they help more people find us.

Next time, on into American history. The continuous remaking of race theory and whiteness. Including the vigorous efforts by some to put a scientific stamp on racism.

Janet Monge: He was just really interested in the classifications that are associated with cranial capacity, measuring the inside of the skull bones…. The natural superiority of white people, of Europeans.

Biewen: He was trying to prove that, basically.

Janet Monge: Yes. Yes! And in the best scientific terms that could be applied in his time.

John Biewen: The editor of the Seeing White series is Loretta Williams. Music in this episode by Kevin MacLeod, Blue Dot Sessions, and Lucas Biewen. Scene on Radio comes to you from CDS … the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University.

Teaser photo credit: Meeting of the Virginia House of Burgesses, 1619. Library of Congress.