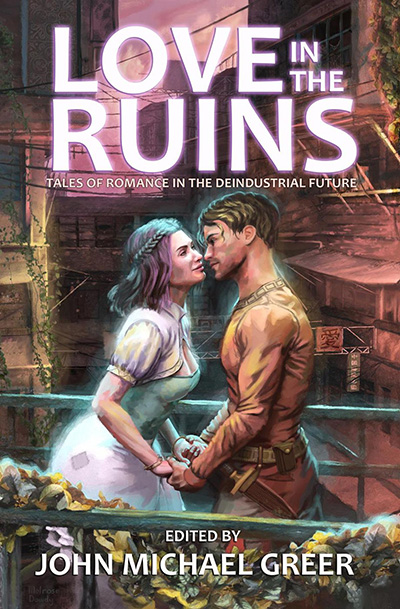

Love in the Ruins: Tales of Romance in the Deindustrial Future

Love in the Ruins: Tales of Romance in the Deindustrial Future

Edited and introduced by John Michael Greer

Paperback, 5.5″ x 8.5″, 275 pp., $15.99.

eBook formats: ePub Edition, file size: 4 MB, $5.99; Amazon Kindle Edition, file size: 4 MB, $5.99.

Founders House Publishing, Apr. 2020.

Perhaps the most striking feature of this anthology of stories and verse about romance in the deindustrial future is its rich assortment of tones and styles. Some stories are charming, others throb with as much trauma as passion and still others feel as timeless as myths. The poems are equally diverse, ranging from the mathematical precision of a villanelle, to heroic verse in the fashion of an Old English epic, to a stark cautionary poem. All of this makes Love in the Ruins a terrifically fruitful union between traditional romance and the nascent but vibrant genre of deindustrial science fiction.

The book is the result of a fiction writing challenge posed by its editor, John Michael Greer. An accomplished author in his own right, as well as a scholar of the rise and fall of civilizations, Greer has been holding writing contests as a way of spurring others to imagine what could lie ahead for industrial society. The entrants in these contests tend to be readers of Greer’s blogs (both his current blog, Ecosophia, and its predecessor, The Archdruid Report) on the subject of civilizational decline. As evidenced by the caliber of their discussions, Greer’s readers are an erudite and inquisitive bunch—and, as Greer was delighted to discover during his first contest in 2010, quite a few of them also possess legitimate writing chops. This volume, together with the superb After Oil series, also from Founders House Publishing, marks the culmination of Greer’s writing contests thus far.

To those familiar with the conventions of deindustrial sci-fi, it isn’t spoiling anything to say that these stories take place in dark futures. And those familiar with the cardinal rule of romance fiction will know that despite this darkness, each tale ends happily as far as the romantic pair is concerned. That payoff at the end is especially welcome in the two bleakest entries in this anthology, both of which involve people being imprisoned for petty crimes without due process and being horrifically mistreated while held captive. In Ben Johnson’s “At the End of the Gravel Road,” an internment camp inmate and one of her minders fall into each other’s arms during a time of intense shared trauma. In Ron Mucklestone’s “A Nuclear Tale,” an escaped prisoner has to warn his newfound love that the poisoning he received during his sentence—which entailed handling spent nuclear fuel—has increased his risk of an early death, and thus if they forge ahead with their relationship, he may be condemning her to premature widowhood.

A recurrent theme in this collection is that as the threat of mortal danger grows more acute and ever-present, so do lovers become increasingly passionate in their affections. Justin Patrick Moore’s “Shacked Up” and Violet Bertelsen’s “The Doctor and the Priestess” are portraits of torrid love relationships set against backdrops of savagery and casual violence. Both pieces involve arsonous rampages committed over betrayals of loyalty, and both exude a live-hard-and-die-young ethos.

Somewhat less oppressive in tone than the three pieces summarized thus far is C.J. Hobbs’ “Letters from the Ruins.” A tale of forbidden love and a fine example of a love story within a love story, this one takes the form of a series of letters from a woman to her long-lost love, framed by a tale set many years later, in which one of the woman’s descendants reads the letters. An elder of his has asked him to read them in order to understand why his family and friends are against him marrying his girlfriend. It turns out there’s a violent history between their two families.

Marcus Tremain’s “Neighborhood Watch” and Daniel Cowan’s “Working Together” deal in infatuation rather than love, though they’re no less enjoyable for that. My favorite of these is Cowan’s piece, which tells a sweet tale of two hopeless introverts finding each other. Katarina wants to go into the bookstore business but is thrust into the position of running her family’s restaurant instead. Philip is a farmer passing through town. Their first meeting is adorably awkward and ends with Katarina buying produce from Philip. This initial transaction leads to an ongoing business relationship, which in turn gives way to romance. A particular strength of this story is its sumptuous descriptions of the fancy dishes served at the restaurant, a fitting touch given that Cowan’s about-the-author blurb says he’s spent much of his career as a cook.

In a similar vein to that of Cowan’s story is “Courting Songs” by Tanya Hobbs. Set in a vast, forbidding desert region of Australia, it likewise breathes new life into the trope of the small-town local and the out-of-towner who discover they’re soulmates. The two love interests are Red, an itinerant trader, and Johannes, a prominent but reclusive resident of one of Red’s trading stops. Theirs ends up being an arranged marriage, though that doesn’t make them any less desirous of going through with it. Perhaps more than any other author in this collection, Tanya Hobbs shows a wonderful ease with narrative-driven storytelling, a fine ear for dialogue and a supreme talent for world building, all of which make this easily the most accomplished of any of the stories.

The heroic poem I alluded to earlier is “The Legend of Josette” by K.L. Cooke. In addition to being a love story, it’s an account of the mythical woman of its title. Josette is part Beowulf (battling humongous bears and an alligator named Old Satan) and part Queen Hatshepsut (donning an artificial beard and changing her name to Joseph so she can reign as a king although a woman). The one thing that detracts from my enjoyment of the poem is that its opening epigraph is a misquotation. It quotes the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius as writing “Fame after death is no better than oblivion,” when in fact he wrote “Fame after life is no better than oblivion.”

This brings me to the one fault I have with Love in the Ruins overall. The version of it that I read, the ebook, unfortunately contains a good deal more mistakes than one would expect to find in a professionally published book. In addition to the misquotation noted above, the book is inconsistent on the names of a couple of its contributors, with one of them acquiring a new last name from one reference to the next, and another a new set of beginning initials. There are also many mechanical gaffes, including misspellings, mistaken use of the contraction “it’s” in lieu of the possessive “its,” omitted or misplaced commas, missing possessive apostrophes, missing paragraph indents, wrong words and homophone errors. I’m told that a lot of mistakes have been corrected for the paperback edition, and thus I would recommend buying that version instead of the ebook. The outstanding craftsmanship and artistry of these stories and poems warrant a first-rate editing job.

The remaining works are an interesting and unfailingly imaginative mix. Al Sevcik’s “Forest Princess” manages to rejuvenate the second-chance-at-love cliché by capping it off with an exciting gunslinging showdown. Catherine Trouth’s poem “The Winged Promise” is an elegy for a long-ago crashed airplane and the miracles its existence once enabled, including “clothes so fine, / Then your lover can your devotion flaunt.” Troy Jones III’s “Come Home Ere Falls the Night: a Ruinman’s Villanelle” is just the sort of folk rhyme I can imagine ruin excavators of the future singing around campfires as they long to return home to their families.

The book’s final piece, David England’s “That Which Cannot Be,” returns to the theme of forbidden love. Set in an unspecified region of a far-future Earth whose sea levels have drastically risen, this story depicts a tribal race that believes its island chain to be the last remaining land above water. Our main character is in love with a fellow member of his tribe, despite a prohibition against intratribal marriage. When the two of them set off in search of other lands in which to build a life together, they bring us along on a rousing adventure that plays out like a retelling of some legend recounted since time immemorial. This story is absolutely the right one to conclude the collection, its folktale-like tone leaving us with a sense of mystical enchantment.