A growing movement of gardeners — from ethno-botanists to green-thumb hobbyists — is committed to spreading awareness of methods for enhancing the intricate ecological relationships in local spaces. Even more significant is how the interconnectedness of this knowledge can make a ‘global’ difference to landscapes everywhere.

Your garden as social science lab . . . Insect hotels attract wood-nesting insects. [o]

Chickadees are tiny little birds, weighing less than half an ounce when full-grown. They can fit easily in the palm of a child’s hand and are named after the sound they make — ‘chick-a-dee-dee-dee-dee.’ It might be surprising, then, to learn that it takes thousands of caterpillars to raise a single nest of young chickadees.

“When a chickadee lays its eggs and starts to raise its young, it becomes a specialist in caterpillars,” says Monty Caid, president of Lost Foods, a Eureka, California-based nonprofit dedicated to restoring native plant diversity and abundance. It’s a sunny Friday afternoon in September and he’s speaking to less than a dozen local residents gathered for a tour of the Lost Foods Native Plant Sanctuary and Nursery.

“All day long it’s going around collecting caterpillars to feed its young,” he says. A single pair of breeding chickadees, according to a study from the University of Delaware’s Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology, gathers between 6,000 and 9,000 caterpillars to feed one nest of baby birds. “And that’s why butterflies lay tens of thousands of eggs on the plants and you don’t see them being defoliated,” he says, “because every day birds are picking off these insects.”

In turn, caterpillars and other insects depend intimately on just one or a small handful of native plant species they’ve co-evolved alongside. “Plants develop chemical defenses to make it harder for every species to eat all their leaves,” Caid explains. “And so insects over time developed special relationships with plants; they’ve figured out over thousands of years how to digest these toxic chemicals and actually use them to their benefit. But the problem is, in order to do that, they have to specialize.”

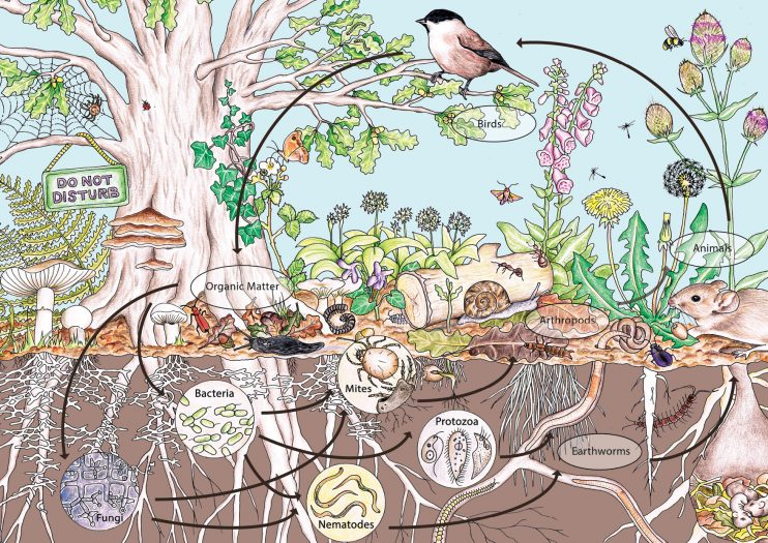

Together, plants, and the insects that depend on them, nourish the entire food web: an interconnected network of delicate relationships. “If you’re not able to eat plants, you’re either eating the insects that ate the plants — or you’re eating other species that depended on the plants or insects to live,” Caid says.

Here, like at many points during this brief but loaded presentation, I’m struck with the undeniable interdependency of everything. This isn’t news to me, as I teach, write and think about relatedness in my work and my life everyday. But there’s something about Caid’s particular gathering of facts and anecdotes — information he conveys calmly and matter-of-factly — that seems simultaneously tinged with a quiet urgency, a near-desperation stemming from deep awareness and empathy in a time of ecocide. I recognize his sense of eco-anxiety, heartbreak and hope because it mirrors my own.

Monty Caid is one of many whose native species focus is changing the way we think about our local spaces. [o]

Caid, 39, is a self-taught native plant horticulturist and founder of Lost Foods. He grew up in Oakland, poring over his mother’s books of herbal remedies. “We’d look through those books and find things good for your brain or heart or lungs and make our own little magic potions,” he recalls. They moved to Humboldt County in 2002, where Caid grew increasingly interested in native plants as a pathway to restoration and resilience. In 2007 he quit his job as an auto mechanic to focus fully on tending plants; five years later he founded Lost Foods. Standing in the three-quarter-acre sanctuary and nursery today, you’d have no idea that this small corner of the city’s fairgrounds was last used as a garbage dump. The place is teeming with vibrant life, making the realities Caid shares with the small crowd feel a world away.

“We’re going through an extinction crisis right now,” he says in his characteristically soft but resolute way. California has been particularly hard hit, he says, its well-known status as a ‘biodiversity hotspot’ juxtaposed to its number of threatened or endangered species, more than 300. Of the US states, only Hawaii has it beat — at nearly 450. The more you have, the more you have to lose.

Systemic annihilation and reproduction of landscapes globally have fueled massive habitat loss, says Caid, citing rampant deforestation and commercial logging, the eradication of diverse forest ecosystems replaced with timber monocultures, as well as urban sprawl and industrial agriculture. Growing non-native species un-adapted to local climate and soils — coupled with corporate agriculture’s mandate to produce as much of a single food commodity in a given space as possible — requires excessive amounts of water and synthetic chemicals, harmful to humans and nonhumans alike. Here it is again, the violent replacement of polyculture with monoculture. Once you’ve got the pattern, you see it everywhere.

To feed their young, chickadee parents must find anywhere from 6,000-9,000 caterpillars, one reason why butterflies lay tens of thousands of eggs. [o]

Collectively, this causes a catastrophic loss of ecosystem function. “Ecosystems are…built of native plants and native wildlife that depend on the plants,” Caid tells us, “and they interact together in a symbiotic way that creates diversity and abundance and resilience. When you remove a native species from an ecosystem there’s a chain reaction from all the other species — ones that might have depended on that species — that is now missing. It causes a chain reaction of extinction.”

The roots of this crisis, Caid suggests, converge in human exceptionalism — the cultural belief that humans are separate from and dominant over nature. “I always believed that humans are supposed to be part of nature,” he says. “And we’re supposed to be a beneficial part. So even though there are billons of people on the planet, the reason why we’re not beneficial is because everything we touch, we destroy or alter. We just don’t know how to live correctly.”

Not simply overpopulation, then — not ‘just human nature.’ Our crisis stems from a story the dominant culture has told itself for centuries, one of fragmented relationships and consciousness. But, Caid believes, it’s a story that can change and must change.

A black-capped chickadee’s universe . . . abundant spaces provide food, fibre and energy while building fertility and repairing the ecosystem. [o]

“If you have billions of people on the planet,” he says, “and we all start restoring native plants, we could fix the problem in, like, a year or two. You become a beneficial species of your local ecosystem. You start to learn the uses of these plants, and you start to grow them — for wildlife, but also for your own health, for your own medicine. . . We can be a little selfish about it. This is about human survival, too.”

The shift, Caid says, can start, literally, in our own backyards, by which he joins a growing community of folks calling for a transition as to how we understand and use our living spaces. “Even if you convert just half of your yard to native plants,” he says, “it provides this resource where species can move.”

Mainstream conservation’s strategy of wildlife preserves and protected land — beyond displacing indigenous groups who have long been part of the ecosystem — has created pockets of biodiversity without considering the linkages. “Species need to migrate, and they need to be able to find food as they go,” says Caid. “But the spaces between our preserves are too big for species to do that. If we incorporated more native species into our yards, we could create the biggest homegrown national park — creating native plant migration jump spots throughout the country. And that’s what we need to do to save our wildlife.”

It’s clear that our challenge is one of cultivating diversity and creativity in our daily human practice; we are called now to re-imagine. For this, we need spaces that can show us, through all the senses, what has been and what could be, spaces that heal, teach, inspire and enchant — spaces like this one.

“The goal of the sanctuary was to put as many diverse native species in a space as possible,” Caid says, “to give people a place where they could actually see plants that are native here. To get people to see it, you have to show it to them.”

Beyond inspiration and education, the nursery provides a bountiful source of edible native plants for local yards and gardens, many of which contain incredible amounts of nutrients for human and nonhuman species alike. Blue elderberries, for example, are growing prolifically in the sanctuary. For his visitors, Caid has harvested some and baked them into muffins. He highlights them on the walk-through tour, along with Western Chokecherry, a delicacy used in pies, jams and wines. Also, Black Hawthorn, used to treat diseases of the heart and blood vessels; Oregon Grape, excellent for liver and blood purification; and the Woodland Strawberry, a delicious native berry that doubles as a productive ground cover.

Caid at work in the Lost Foods Native Plant Sanctuary and Nursery — “a wasteland turned abundant”. [Author photo.]

Also thriving in the sanctuary, to name a few, are California hazelnuts and red huckleberries, Klamath plum and clarika, currants and gooseberries, checkerbloom and serviceberries, Pacific madrone and tanoak, grand fir and Sitka spruce, red cedar and western hemlock, Douglas fir and redwood. To be surrounded by so many species in such a small space is invigorating, enlivening, almost dizzying.

Here in a wasteland turned abundant, Monty Caid — inspirational ethno-botanist, gentle natural healer, deeply kind human being — has put on vivid display another way to be in the world. Insects hum around us, birds call to one another, and I recall the tiny chickadee and the radical revelation that something so small can loom so large in our collective future.