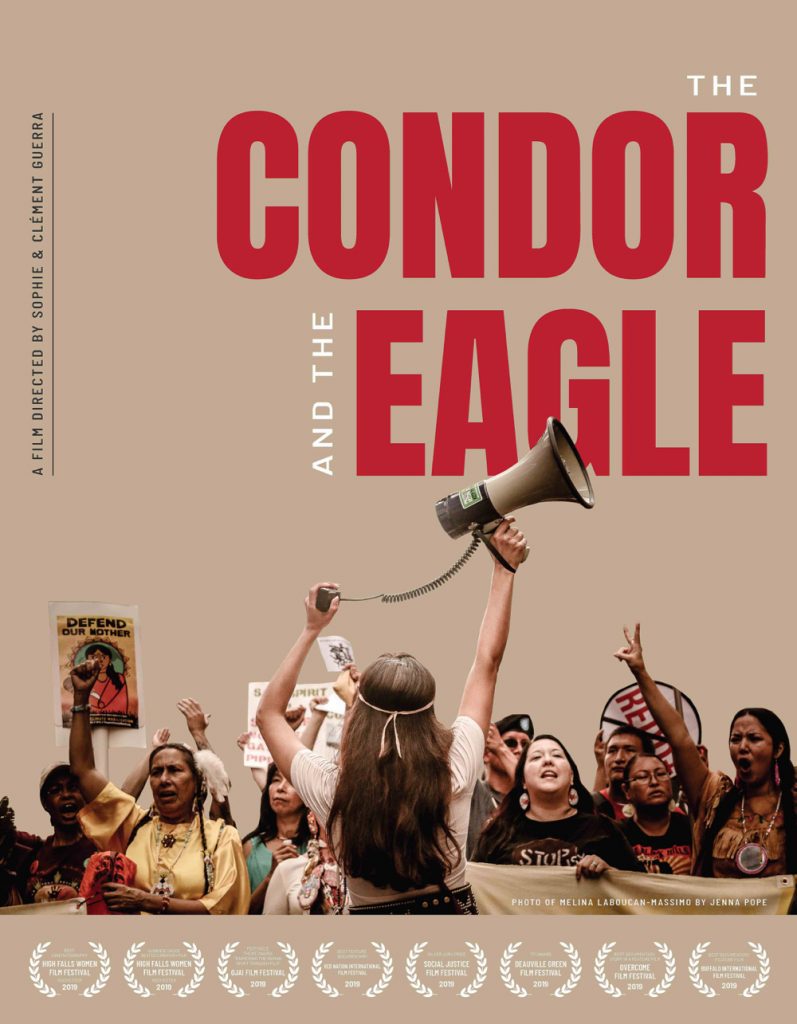

From the tar sands of Alberta, Canada, to the oil fields of Texas, to the Ecuadorian Amazon, The Condor & the Eagle tells the story of the collective struggle of the Indigenous peoples of North and South America in their fight to preserve their communities and to protect the Earth from climate change. It took the directors five years to finish the film, which premiered at the Woodstock Film Festival in New York State in October 2019. It is also a story of solidarity among Indigenous women of the Americas as they have come together to protect First Nations women from exploitation and violence.

This 2019 feature film was directed and produced by Clement Guerra, a 37-year-old French international marketing manager working in London, and his German wife Sophie. The couple left their comfortable careers in Europe and took their savings to live in a camper van and spend five years documenting the Indigenous-led climate justice movement.

There are thousands of pipelines across the US and Canada. However, two pipelines, among others, have captured broad public interest: the KXL pipeline (from the Alberta tar sands to Houston) and the TransMountain pipeline (from the tar sands to Vancouver — for shipping to China and the Asian market). The pipelines made people and communities realize that they are equally affected by environmental risks. Large environmental organizations such as 350.org have made it their duty to stop KXL, and the oil pipeline resistance has become emblematic within the environmental movement over the past few years. The civil society movements against those two pipelines energized the amazing mobilization at Standing Rock.

In this exclusive interview, British author Linda Etchart talks to Clement about the making of the film, and the ways in which the project has created links among Indigenous communities across the American continent. The interview has been updated and edited for clarity.

Check out The Condor & The Eagle website to find upcoming events as the social impact team prepares for the July 1 online launch (pre-order here)

Can you tell me what gave you the idea for the film?

Both Sophie and I come from marketing and health backgrounds; we did not intend to produce a feature film. We wanted to use our media and community organizing tools to support the climate justice movement and facilitate regional and international alliances. After two years of travelling around the American continent, we made 12 short videos centralizing environmental issues. Within six months, we realized a bigger story needed to be told to the world.

As we took a step back, we realized that the dots connected and that these short stories, seemingly isolated, came together organically into a feature film format. The Condor & the Eagle is our first full-length documentary: it has already been selected by more than 50 film festivals across North America and has won 12 awards, including Best Documentary Film at the Red Nation International Film Festival in Beverly Hills. The film premiered at the Woodstock Film Festival in New York State in October 2019.

Bryan Parras, left, and Clement Guerra receiving an award at the Red Nation Film Festival.

Can you tell me more about yourselves?

Sure, I am French, and I co-directed the film with Sophie, my wife, who is German. We live in Germany with our two beautiful babies. We needed five years to finish this film, from development, to filming, to production and post-production, before we presented it at the Woodstock film festival.

We had several options: Sophie was studying pharmacy and I was an international marketing manager in London. We could have just settled down to a comfortable middle-class life, but we were aware of how western countries were treating the environment, and were interested in learning more about it, especially what was happening in the US, because we had heard about the ecological destruction there. So we took our savings, flew across the ocean and arrived in Washington, D.C. We had heard about a gathering of the Cowboys and Indians Alliance, where the oppressor and the oppressed would come together and unite their efforts to expose the destruction taking place as a result of the laying of oil pipelines.

We quickly realized that this was the beginning of the global climate justice movement. It was at the time of the Keystone XL pipeline. Pipelines are damaging the environment, but they also affect communities, as they have done in Canada and in Houston, Texas. We started to educate ourselves on global issues and how the topic of the pipelines was bringing people from all sorts of backgrounds together, and also how the native peoples and the children of the colonizers were coming together.

Pelican flying past an oil refinery in Texas City.

Energy companies are actively planning to triple Canadian tar sands production (the world’s largest industrial project) in the coming years, which would mean “game over” for climate change. Such an increase in production is possible if the planned pipelines are actually built and permitted in the US and Canada. The pipeline movement is to a large extent the origin of the global climate justice movement. Our four protagonists live alongside the pipeline routes and have played key roles in the fight against the oil pipelines.

We knew that we had to look at the situation in Houston, the underbelly of the beast, and one of the energy capitals of the world. We tried to contact Bryan Parras, co-founder of the pioneering environmental justice group Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services (TEJAS), and now spearheading the Texas Beyond Dirty Fuels campaign of the Sierra Club. We stayed in Houston for a while, doing research, and then we moved to the Bay Area in San Francisco.

We found the situation very interesting there. Many communities who were on the frontline of industrial development were starting to work together to challenge the refineries that were trying to get the special permits needed to receive oil from the tar sands. So we realized that the tar sands issue was much bigger than we had previously imagined. We started to interview and film communities affected by it, and we put together a short film. We received good initial feedback; the people liked it, so we decided to carry on travelling and support local communities with our media work.

We heard about an interesting gathering taking place in Canada: the Tar Sands Healing Walk, which was planned to circle the industries near Fort McMurray, Alberta, a Northern Canada town that has played a major role in the development of the Athabasca oil sands.

We were just living in a small camper van, so we drove the 1,000 or so miles to get there. That is where we finally caught up with Bryan Parras, who we would end up following back to his home in Houston at the other end of the planned tar sands pipeline. We also made another important connection: Melina Laboucan-Massimo, a member of the Lubicon Cree First Nation and one of the organizers of the Healing Walk. She had not been able to attend the walk but we got hold of her and met with her for a first interview. She then invited us to take part in a community gathering in memory of her sister who had been murdered a year prior.

Casey Camp-Horinek and Melina Laboucan-Massimo leading the People’s Climate March in New York.

We witnessed the health issues of the local residents: An unusually high number had developed chronic respiratory problems and cancers and suffered from social ills such as unemployment and alcoholism. We also saw the pollution caused by the industry in the city of Fort McMurray, where thousands of oil workers live. These were all migrant workers from other regions, with no attachment to the land, and they were wasting the good money they were earning.

We then flew over the area and went deep into the boreal forest that surrounds Fort McMurray, spending two weeks in the remote downstream community of Fort Chipewyan. This community captured the attention of the media because of the high death rate and the many cases of cancer occurring there.

Visiting with the people in these communities helped us to understand the impact of the industry on communities living downstream and suffering from the toxic effluents from the tar sands extraction.

How did you decide where to go from Alberta?

While we were working in Alberta, Melina let us know that something big was being organized in New York — the People’s Climate March — and she advised us to go. We flew to New York and we didn’t know what to expect. We were amazed as half a million people made their way down the streets of Manhattan, marching for climate justice. When we realized that Melina was leading the way, in the very front row of the march along with the charismatic Ponca leader Casey Camp Horinek and other Indigenous women from the North and the South, we understood that our story was much bigger than we had initially thought. Literally, Indigenous women from the North and from the South were leading the way!

Indigenous-led People’s Climate March, New York, 2014

We were very impressed by the fact that they commanded so much respect in that massive rally. Also in the front row were several women from Ecuador: global environmental leader Patricia Gualinga, of the Sarayaku Kichwa Ecuadorian Amazonian community, and Gloria Ushigua, a leader of the Sápara community, among others. And that is when I started to listen to Patricia, who was saying that the Global North and the Global South had to join hands and also to liaise with the Rights of Nature movements and the Indigenous communities’ legal challenges to mineral extraction on their lands.

It was at this historic event that Indigenous women from the North met with Indigenous women leaders from the South and initiated relationships and began building rapport, which would grow into long-lasting relationships in the years to come. This event would provide insights and connections that continue to guide us to this day.

After New York, we traveled to Houston and worked with Bryan.

Clement and Sophie with their camper van

I understand Houston played a big part in the film, as well. Can you talk a little bit more about that?

Houston is the energy capital city of the world and plays a key role in the whole oil and gas system. Houston refines the oil coming from the whole country and would indeed play a key role in refining and shipping the oil that would come from the tar sands — brought down by the KXL pipeline. Our two main protagonists are Bryan and Melina because they each live on the opposite extremes of the chain of destruction: Melina in the tar sands region, where they extract this extreme fossil fuel; and Bryan in Houston, where they refine and ship the tar sands coming from Alberta. This is how North America is somehow connected, by the pipelines transporting this sludge from Northern Canada to the Gulf of Mexico.

This pipeline issue is key, because if the pipelines (KXL, Transcontinental Pipeline, etc.) are permitted and built, that would mean a threefold increase in production of tar sands — which would mean Game Over for the climate, as the extraction of tar sands produces three times more CO2 than traditional oil.

We then drove to Ponca, Oklahoma, where we met and worked with Casey Camp Horinek.

Casey Camp-Horinek at the Cowboys and Indians gathering in Washington, D.C.

Can you discuss your connection with Casey, and explain the role of the Ponca people in all of this?

At first Casey was reluctant to have two white, privileged Europeans telling the story of Indigenous people; she told us that her whole life had been dedicated to empowering her own people so that they could learn to speak for themselves. But when we shared with her our intention to make a film about the importance of creating alliances between the Global North and the Global South, she started taking our project seriously, as it was exactly what she was working on at the time.

We told her that we had been travelling in our camper van for many months, from community to community, and that our hearts then told us to go to South America. She then told us that she had also been praying for that to happen. She gave us her blessing and our film was set in motion.

So we were on. We led a successful crowdfunding campaign, which allowed us to fundraise to support the alliances that were taking place between the North and the South. Casey and the other leaders who ended up being our protagonists were already developing partnerships with communities living in the Amazon. We didn’t interfere; we only raised the financial support for the already-existing-initiatives to travel to the Amazon and consolidate alliances there. Casey was planning to join us on the journey but had to cancel at the last minute because a close friend of hers had just suffered a tragedy.

So we managed to raise the funds to cover the expenses of four of our protagonists, who flew separately to their communities in the Amazon rainforest in Ecuador and Peru. For practical reasons we managed to shoot the Peruvian section near the Ecuadorian border.

So that is how we organized our storyline through the journey of our protagonists from North America to the South American rainforest in order to build meaningful alliances in the South.

Co-Director Sophie Guerra in Northern Canada, in the community of Fort Chipewyan

Can you talk about the approach you took to the filmmaking process itself?

The Condor & The Eagle tackles complex issues in numerous regions in the Americas, issues most of the audience might be oblivious to. The film avoids the traditional documentary techniques of interviews and voice-overs; instead, the story is told through unfolding action and interactions amongst characters; while it was not easy to create, it was definitely rewarding. The documentary allows indigenous and impacted communities to speak in their own voices, unlike most social justice documentary films. Directing a film on grassroots resistance doesn’t need to be patronizing as long as we build a storyline based on the emotional journey of “normal” people striving towards achieving personal goals. Our program had to leave most of the politics aside by weaving a tale of inner strength and inspiring courage.

Could you please tell us about what happened when you got to Ecuador, and when and how you interviewed the Sarayaku-Kichwa people? Why is Ecuador important in your work?

First of all, could we talk a bit about the spirit of the rainforest? It is something that white people going there do not easily understand. In the climate and environmental justice movements it is usually said that people will not defend something they do not have a feeling for. Why would you actually defend something you don’t love, or of which you don’t have personal experience? So we tried to immerse the protagonists and the audience in this magic, so they could bounce off of it.

Gabi Aguilar, founder of Los Yapas, reforestation project in Ecuador

In the Sarayaku-Kichwa culture, they have a philosophy called kawsak sacha — “the living forest” — meaning that the forest is not just a bunch of trees or animals or insects; it is more than that, it is the spirit of the forest that contributes to the balance of the natural world. When colonialism encroaches on the Amazon forest, the spirits die; if the current destruction continues, the equilibrium of the planet will just collapse. So what is happening in the rainforest affects us all, and also our economic and political system.

What is also amazing is that in Ecuador and close to the Colombian border, Chevron/Texaco spilled millions of gallons of oil, creating an environmental nightmare and producing terrible toxicity in the rivers, and yet, not that far away, there are still areas of pristine biodiversity. That is mind-blowing when you consider how close to that region natural habitats were totally destroyed.

Patricia Gualinga speaking up about the “Living Forest” at the People’s Climate March in New York City

As we started to work there we heard that the government was planning to sell the land to Chinese industries, in a country like Ecuador, which was the first country to enshrine the Rights of Nature in its constitution. So that was a big contradiction, to put it mildly. So we knew that we had to involve the protectors of the land, especially the Sarayaku-Kichwa, who for generations have been the protectors of the environment and have led the way in enforcing prior consultations — “free, prior and informed consent,” according to national and international law — with local communities in countries where the governments were planning to sell or exploit their land. Indigenous people form 5% of the population of the planet, but they live on 20% of the land and 80% of its biodiversity, so naturally, they have to be consulted! You remove the Indigenous people and the game is over for the planet.

So we started with the tar sands, now the largest extractive industrial project in the world, and our priority was to support the Indigenous communities protecting the land and to see how the Northern and Southern global alliances could work together.

It was very important for us that this film would not just end up being an “activist” piece of work. We also wanted to show how many of the Indigenous communities had no choice but to work in the extractive industries, and that many of their members were supportive of those industries because of the job opportunities they provided, especially after losing their traditional lands. So we wanted to show their side of the story, as well as that of those who wanted to keep the oil in the ground.

Whatever happened with the Chinese industries in the Sarayaku-Kichwa territories?

Industries have indeed started drilling in Yasuni National Park. Sarayaku and surrounding communities have so far managed to keep the industries away from their lands.

The Yasuni National Park is one of the most biodiverse places on the planet.

There are a number of communities where increasing numbers of people are working for the oil companies, and there are increasingly fewer individuals who are resisting them. The oil companies are paying large sums of money, buying the support of the communities, particularly from those who do not have other sources of income. So how do you see that question?

That is a very good question; our film is just a film, but when we travelled, we were involving the local communities in the process of making it. We would show our work in progress, depicting how the communities most affected by extraction, although struggling to survive, were actually at the forefront of shaping the movement of tomorrow. Our film also shows that impacted communities define themselves by the feeling of isolation. They are saying: “We were left alone, the government has abandoned us, we die of cancer and other illnesses.” And we highlight in the film how those impacted communities can actually make the difference and lead the way forward.

Unlike so many depressing environmental films, ours is deeply empowering and presents itself as a handbook for social movements and cultural change. Indeed, our story starts small with local impacted marginalized individuals who decide to no longer accept to be the victims of an unjust system. Overcoming the feeling of isolation, they manage to grow regional support networks, progressively gaining national visibility. Eventually, they rise as international leaders, taking the fight from the streets to the courts (tribunals, consultations and reforms) and inspire others to help change our system’s architecture.

Last but not least, The Condor & The Eagle brings to light the fact that we need a cultural shift and not only a technological revolution. Many people respond to the climate crisis by looking to technology and consumer decisions. By focusing on Indigenous people, The Condor & The Eagle shows that without systemic changes in our culture and values, we will never recover from the destructive path on which we are embarked.

Majestic condors in Colca Canyon, Peru

Now that the film is done, how will you distribute it — and how has the global pandemic affected your strategy?

We have decided not to rush things by selling our film rights to TV channels as it would somehow mean that we are stealing the film away from communities and groups who can benefit from organizing around the screening of The Condor & The Eagle. We are therefore taking the steps needed to “liberate” the film. For now, we are handling its distribution ourselves, independently. It is exciting but it definitely represents a lot of hard work — we hope to succeed as we already have powerful and long-lasting partnerships in place.

Before the pandemic forced us to shift our strategy, we were planning hundreds of community screenings with our key partners, which would have been taking place as we speak: Unitarian Universalist Association, Council of Canadians, David Suzuki Foundation, Indigenous Climate Action, and others. We are adjusting to the pandemic by “going virtual” with the film’s impact campaign, which in a way allows us to broaden the scope of our film outreach. We are currently offering the opportunity for groups / collectives / congregations to push the cause for Environmental Justice by using the film as a visual tool. Our award-winning documentary launched online for Earth Day on 4/22 with the participation of many hundreds of people from more than five countries. Many communities and partners have already responded positively to our initiative to “go virtual” as they are excited about the possibility of continuing to get together despite the isolation many feel due to COVID 19, organizing online HD screenings, live Q&As, discussion forums and joint fundraisers.

By bringing a diversity of groups together online, we can build a more effective movement as we launch powerful calls to action. Key environmental justice coalitions have joined our initiative and are currently hosting online events using our film as an organizing tool. We are collaborating with groups such as the Powershift Network (a coalition of 80+ youth groups), Climate Strike groups, interfaith groups, Australian youth organizations and member groups of the divestment movement.

Each screening is the occasion to raise funds for our impact campaign and helps seed more projects in the coming years. Likewise, we are encouraging groups and organizations to use the film as a way to elevate and amplify local grassroots campaigns and issues.

Indigenous people marching against the oil sands at the “Healing Walk” in Fort McMurray

The highlight of our organizing work will be a series of events leading up to the international release of our film on VOD (Video on Demand) on July 1. The Condor & The Eagle is already available for pre-order HERE. Every day, from June 21st to June 30th, one of a series of partner organizations will host one of our free online events, presenting to large audiences the inspiring work being done by land defenders across the world.

We are hoping to have more than 20 online events in the month of June, which will involve 50+ communities and environmental groups, trigger debates around urgent issues / actions and raise thousands of dollars to keep supporting the critical work of those on the frontlines — full list of events HERE. Hopefully, many more organizations will recognize the high potential of such collaborative events and will jump on board, growing this “online movement” over the summer and beyond!

In the longer term, by showing the film and by setting up storytelling workshops throughout North and South America, organizing events and working with social media partners in different forums, we can keep supporting community-led initiatives to reach out to others in order to build alliances, to network and gain visibility. We strongly believe that such organizing work can make changes happen. We are hoping to keep raising funds through our work in order to support Indigenous and other community leaders to carry on their work, and also to use these platforms to come together. Groups, organizations and communities can request an online screening HERE.

Our work has not finished with the film; we are just getting started! We hope that in a few years, we will be unemployed, because, by empowering communities, they will be able to tell, and document, their own stories. And that is our job; not to jump to the next story just because we want to make films, but rather, we want to understand why we are making films, and to give back to the communities. We don’t want to be “extractivist” filmmakers, but rather, ones who work hand-in-hand with communities.

Winning film awards shouldn’t be a goal in itself, and media work can also be understood as a service to others and a contribution to social change. On a personal level, this whole experience helped us face our own privilege, and we quickly realized that the pollution outside reflected the ego-toxicity we are carrying on the inside. We have been conditioned to believe that we are skin-encapsulated egos, that we are each an “I” separate from every other “I.” Interconnection is a central core of First Nations’ worldviews and ways of knowing. Thanks to our journey and the process of making this film, we came to realize that we all depend on each other, we are not separate – we are strongly connected to the communities we live in, our ancestors and future descendants, the land we live on, and all of the plant, animal and other creatures that live upon it.

Now that our documentary will be distributed to hundreds of communities throughout the world, we are inviting people of privilege to follow in our footsteps and join the call from Indigenous and impacted communities. By filming the protagonists traveling into the heart of the Amazonian forest, we illustrate how the direct relationship between people and nature presents itself as a way out of our colonial imprint.

While our governments and financial organizations are leading us down the path to our demise, more and more people are working towards reclaiming our native land, within — this space within our hearts that is not tainted by this destructive ego-driven system that seeks only self-interest. Beyond fighting for what we do not want, many communities are emphasising solution-based approaches.

We are inviting you all to join us on the journey towards rediscovering our natural roots.

Youth Climate Strike, New York City, 2019