Citrus fruits (oranges, lemons, mandarins, tangerines, grapefruits, limes, pomeloes) are the highest-value fruit crop in terms of international trade. Citrus plants are not frost-hardy and can only be grown in tropical and subtropical climates – unless they are cultivated in fossil fuel heated glasshouses.

However, during the first half of the twentieth century, citrus fruits came to be grown a good distance from the (sub)tropical regions they usually thrive in. The Russians managed to grow citrus outdoors, where temperatures drop as low as minus 30 degrees Celsius, and without the use of glass or fossil fuels.

By 1950, the Soviet Union boasted 30,000 hectares of citrus plantations, producing 200,000 tonnes of fruits per year.

The Expansion of Citrus Production in the Soviet Union

Before the first World War, the total area occupied by citrus plantations in the Russian Empire was estimated at a mere 160 hectares, located almost entirely in the coastal area of Western Georgia. This region enjoys a relatively mild winter climate because of its proximity to the Black Sea and the Caucasus Mountain range – which protects it against cold winter winds coming from the Russian plains and Western Siberia.

Nevertheless, such a climate is far from ideal for citrus production: although the average winter temperature is above zero, thermal minima may drop to between -8 to -12 degrees Celsius. Frost is deadly to citrus plants, even a short blast. For example, at the end of the 19th century, the extensive citrus industry in Florida (US) was almost completely destroyed when temperatures dropped briefly to between -3 and -8 degrees Celsius.

From the 1920s onwards, the Russians extended the area of citrus cultivation to regions considered even less suited. Initially, citrus production extended westward along the Black Sea coast, a region unprotected by mountains, and where temperatures can drop to -15 degrees Celsius. This includes Sochi – which hosted the 2014 Winter Olympics – and the southern coast of Crimea. At the same time, citrus cultivation extended eastward to the west coast of the Caspian Sea, in Azerbaijan.

Citrus production was then spread to regions where winter temperatures can drop to -20 degrees Celsius, and where the ground can freeze to a depth of 20-30 cm: larger parts of the earlier mentioned zones, as well as Dagestan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and the southern districts of Ukraine and Moldova. Finally, citrus cultivation was pushed further north in these regions, where winter temperatures can plummet to -30 degrees Celsius, and where the ground can freeze to a depth of 50 cm.

Frost was not the only obstacle to citrus cultivation in these parts of the world. The region is also characterised by excessive summer heat and strong, dry winds.

From Import Dependency to Self-Sufficiency

Before the first World War, almost all citrus fruits in ancient Russia came from abroad. The main suppliers were Sicily (for lemons) and Palestine (for oranges). Some 20,000 to 30,000 tonnes of citrus fruits were imported annually. Its consumption with tea, the national drink in Russia, meant lemon made up almost three-quarters of these imports.

In 1925, following the Russian Revolution and the civil war, citrus growing became the subject of planned development. The Communist Party was determined to become self-sufficient in citrus production, and no efforts were spared. They set up several research establishments and nurseries, as well as test fields in more than 50 locations.

By 1940, the acreage had grown to 17,000 hectares and production reached 40,000 tonnes, double the annual imports under the old regime. By 1950, the area planted with citrus fruits reached 30,000 hectares (56% mandarin trees, 28% lemon trees, 16% orange trees), and production grew to 200,000 tonnes of fruits per year.

The large share of mandarin trees can be explained by the fact that they are the most cold-resistant of all citrus fruits, tolerating frosts to about -2 degrees Celsius. Lemon trees, on the other hand, are the least cold-resistant citrus variety.

There are three reasons why the Russians managed to grow citrus fruits in regions that were (and are) considered totally unfit for it. First, they bred citrus varieties that were more resistant to cold. Second, they pruned citrus plants in radical ways that made them more resistant to cold, heat and wind. This eventually resulted in creeping citrus plants, which were only 25 cm tall. Third, they planted citrus plants in unlikely locations, most notably in trenches of up to two metres deep.

“Progressive cold-hardening”

Imported citrus varieties only survived in a few isolated points along the Black Sea coast, which enjoyed a particularly favourable microclimate. To better prepare citrus fruits for cold, Soviet citrologists followed a method called “progressive cold-hardening”. It allowed them to create new varieties which were adapted to local ecological conditions, a cultivation strategy which had originally been developed for apricot trees and grapes.

The method consists of planting a seed of a highly valued tree a bit further north of its original location, and then waiting for it to give seeds. Those seeds are then planted a bit further north, and with the process repeated further, slowly but steadily pushing the citrus variety towards less hospitable climates. Using this method, apricot trees from Rostov could eventually be grown in Mitchurinsk, 650 km further up north, where they developed apricot seeds that were adapted to the local climate. On the other hand, directly planting the seed of the Rostov apricot tree in Mitchurinsk proved unsuccessful.

The method, developed following the observation that young plants started from seed adapt to the conditions of the new environment, also proved successful for citrus fruits – which retained high yields and high quality fruits. As well as “progressive cold-hardening”, from 1929 onwards the Russian citrologists performed a methodological selection of cold-resistant varieties, which were hybridised with the best local varieties. This was facilitated by an extensive collection of citrus fruits, which included almost all representatives of the genus Citrus.

Dwarf and Semi-Dwarf Citrus Trees

In the main citrus growing centres worldwide, pruning citrus plants was very rare. Harold Hume, a renowned Canadian-American botanist, even advised to “keep pruning shears as far as possible from the citrus plantation”.

However, pruning was crucial to the cultivation of citrus plants in Russia. First and foremost, pruning reduced the height of the citrus plants. Conventional lemon trees grow up to 5 metres tall, while orange trees can be 12 metres tall. On the other hand, even prior to the 1920s, Russians worked with dwarf and semi-dwarf citrus trees, which were only 1 to 2 metres tall. These trees were further pruned to have compact crowns.

More compact trees have two advantages. First, closer to the ground, temperature variations are smaller and wind speed is lower. Second, smaller trees are easier to protect against the elements. In the region with the mildest climate, where an initial 160 ha of citrus fruits were grown, plantations were often located on terraces or on steep slopes, taking up the smallest piece of land with a favourable microclimate.

“Collecting tangerines at the Chakva state farm”, a painting by Mikhail Beringov, 1930s.

During winter, individual citrus plants in these plantations were protected by a shelter made of cheesecloth or straw mats, supported by a light frame of poles. Plantations were also surrounded by windbreak curtains, arranged in such a way that they mitigated both the cold winter winds and hot, dry summer winds. These curtains also channeled the cold air masses descending from the tops of the hills outside of the plantations.

Further protection against cold and wind was generated by planting trees very close together – up to 3,000 plants per hectare. Excessive summer heat was counteracted by spraying whitewash on the upper part of the leaves, which lowered their temperature by about 4 degrees Celsius. All these methods work for large-stemmed citrus trees, but of course they are much cheaper and easier to perform on trees with a height of only 1 to 2 metres.

Creeping Citrus Trees

Training small citrus plants was key to extending their cultivation across all regions of the Black Sea coast, where until then it had been impossible. This was achieved by pruning and guiding citrus plants into a creeping form, which reduced their height to a mere 25 cm.

The crown of creeping citrus plants was formed in two ways. In the first method, the trunk of the tree took an inclined position as soon as it left the soil. The main branches of the crown, formed in a unilateral fan, touched the ground, and so did the fruits. In the second method, the 10-15 cm tall stem was kept straight while the main branches developed radially at an angle of 90 degrees to the trunk, thus (seen from above) forming a spider-like crown. In this case, the branches and the fruits did not touch the ground, and this proved to be the most successful method.

Creeping culture, here applied to an apple tree. Source.

Creeping citrus trees offered even better protection against cold and wind compared to dwarf and semi-dwarf trees, because the creeping crown created a microclimate that softened both the summer maxima and the winter minima. During a 10-year long test, it was found that in winter, the air layer at the level of the creeping crown was on average 2.5 to 3 degrees Celsius warmer than the air layer at 2 metres above the ground. In summer, during hot weather, the difference in temperature could exceed 20 degrees Celsius.

Wind protection was just as effective. The wind speed at 2 metres above the ground reached an average of 10.4 metres per second, while it was only 1.8 metres per second at the level of creeping lemon trees. This limited dehydration of the crown so that less water was needed.

Logically, the very small size of creeping plants made it even easier and cheaper to protect them against the elements. Moreover, as a protection strategy it proved to be more effective: during the winter of 1942-43, when temperatures along the Black Sea coast went down to -15 degrees, creeping lemon trees protected by a double layer of cheesecloth and by windbreaks did not suffer in any way, while similarly protected taller-stemmed lemon trees froze to the roots.

Perhaps surprisingly, creeping citrus plants had higher yields than semi-dwarf citrus plants. The fruits ripened earlier, and produced more fruits, especially during the first years.

Cultivating Citrus Trees in Trenches

None of the above mentioned cultivation methods were sufficient to grow citrus fruits in regions where the ground froze and where winter temperatures dropped below -15 degrees. Here, citrus plants were cultivated in trenches. Obviously, growing citrus fruits in trenches was only practical with dwarf and – most often – creeping plants. In this method, soil heat protects citrus fruits from frost.

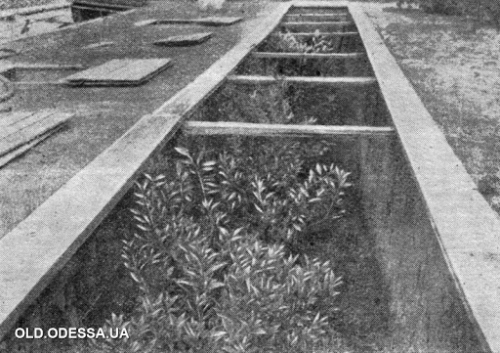

The depth of the trenches varied from 0.8 to 2 metres depending on the winter temperature, the depth to which the ground froze, and the water table. The trees could be planted in single or double rows. Trenches were generally trapezoidal in section to improve light conditions. They were roughly 2.5 metres wide at the bottom and 3 metres wide at the top for single rows of plants, and 3.5 metres wide at the bottom and 4 metres wide at the top for double rows of plants.

If necessary, the walls were coated with clay or reinforced with brick or shell rock. Inside the trench, the plants were positioned 1.5 metres apart from each other, and when two rows were planted, each plant in the first row was located between two plants in the second row. The length of the trenches depended on the nature of the terrain, but did not surpass 50 metres.

Trenches were located on level ground or light slopes, oriented from east to west in order for optimal sunlight during the winter months. They were spaced apart 3-5 metres from each other when they contained a single row of plants, and 4-6 metres when they had a double row of plants. Trenches could be connected to each other, which made it more convenient to care for the plants.

The space in between the trenches allowed for the placing of shade screens or planting of natural shading plants. These increased the humidity in the trenches and protected the citrus plants from overheating in summer.

Covering the Trenches

During the summer, plants received the same care as those planted in the ground under “ordinary” conditions. When winter came, the trenches were covered with 2 cm thick wooden boards and single or double straw mats, depending on the climate. This kept the soil heat in the trench, while keeping precipitation out. If a layer of snow covered the boards, it was left in place for extra insulation. The boards were sloped at an angle of 30-35 degrees. When in winter the temperature rose above zero degrees Celsius, the cover was raised on the south side or completely removed during the day.

This method cannot be applied to any plant. Citrus plants tolerate very low light levels for 3-4 months per year, provided that the temperature of the air in contact with the crown is maintained between 1 and 4 degrees Celsius. At this temperature, the metabolism of the plants weakens, which improves their resistance to cold.

Glass was only used sparingly. Wooden boards gave much better frost protection, were much cheaper, and could be made from local materials. The plants needed some stray light, so that up to a quarter of the trench shelter area was made of glass frames, which were covered with straw mats as well as a top cover of earth and clay. Only a few openings here and there provided light and ventilation.

The cultivation of creeping citrus plants in trenches, although labour-intensive, was a simple method that did not require large investment, and provided high yields (80 to 200 fruits per stem per year) as well as high quality tropical fruits. All types of citrus fruits were grown in trenches.

Other Cultivation Methods

Apart from trenches, Soviet citrologists used other types of shelters to grow citrus plants – all of which were more effective with smaller sized trees (usually dwarf cultures). Some included (usually sparse) use of fossil fuels.

A first example is the cultivation of citrus fruits with annual transplantation. Citrus plants spent the summer outdoors, but as winter approached, they were dug up with the clod of earth surrounding their roots, and transported to wintering sheds, where they were crammed together for as long as it was freezing outside. In spring, they were moved back to their original location. Where the winters were relatively mild, these winter sheds were light wooden buildings that were generally unheated. In colder regions, they were made of masonry, half buried into the ground, and fitted with heating devices.

A limonarium.

Citrus plants were also grown in unheated glasshouses. These “limonaria”, located on the Black Sea coast, were semi-circular glasshouses, built around particularly well-exposed hills with terraces. The trees were grown as espaliers – a method reminiscent of the fruit walls in northern European countries, which facilitated cultivation of peaches and other Mediterranean fruits at high latitudes.

Heated glasshouses, which used electric heating and artificially controlled carbon dioxide and humidity throughout the year, were only used in industrial centers located beyond the Arctic Cycle. Finally, citrus fruits were grown throughout the Soviet Union in pots or boxes in apartments, schools, public buildings, and even in the glass halls of factories and workshops – making use of the waste heat from space heating or industrial processes (steam or hot water).

Few of these methods would have been profitable under a free trade regime. Considerable research investment went into kickstarting domestic citrus production. Although most methods did not require fossil fuels and were possible using cheap and locally available materials, they were very labour intensive. Domestic citrus production was only possible because it was sheltered – not only from frost, but from foreign competition too.

Kris De Decker.

Edited by Alice Essam. Thanks to Alexandrine Maes.

* Subscribe to our newsletter

* Support Low-tech Magazine via Paypal or Patreon.

* Buy the printed website.

Sources:

- Les Agrumes en U.R.S.S., Boris Tkatchenko, in Fruits, vol.6, nr.3, pp.89-98, 1951. http://www.fruitiers-rares.info/articles21a26/article24-agrumes-en-URSS-1-Citrus.html & http://www.fruitiers-rares.info/articles51a56/article53-agrumes-en-URSS-2-Citrus.html

- М. А. КАПЦИНЕЛЬ, ВЫРАЩИВАНИЕ ЦИТРУСОВЫХ КУЛЬТУР В РОСТОВСКОЙ ОБЛАСТИ РОСТОВСКОЕ КНИЖНОЕ ИЗДАТЕЛЬСТВО Ростов-на-Дону —1953. (“Growing citrus cultures in the Rostov region”, M.A. Kaptsinel). http://homecitrus.ru/books.html

- Katkoff, V. “The Soviet Citrus Industry.” Southern Economic Journal (1952): 374-380. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1054452?seq=1. Full version here: https://sci-hub.tw/https://www.jstor.org/stable/1054452?seq=1

- Volin, Lazar. A survey of Soviet Russian agriculture. No. 5. US Department of Agriculture, 1951. https://archive.org/details/surveyofsovietru05voli/page/n3/mode/2up. See page 151.

- Мандарин – туапсинский господин?, СВЕТЛАНА СВЕТЛОВА, 16 ДЕКАБРЯ 2018 https://tuapsevesti.ru/archives/40995

- http://www.agrumes-passion.com/plantation-entretien-f49/topic4913.html

- https://www.supersadovnik.ru/text/yablonya-neobychnye-sposoby-formirovaniya-1003334

- https://selskoe_hozyaistvo.academic.ru/2847/стелющаяся_культура

- http://viknaodessa.od.ua/old-photo/