Overnight, the daily life of the majority of the inhabitants of this beautiful Earth-home has vanished, leaving us in a kind of transitory reality between the old and known and the new unknown. After I asked someone how she was doing a couple of weeks ago, she replied: “Mmm, not very well. The most serious thing is that I have no idea when normality will return and, if it returns, how it will be.” The usual sense of control, security, and continuity of our lives dissolves amid the jaws of the health crisis we face.

In a way, we are like half-cooked beans—we now recognize the transience of our lives more clearly. We are wanting to finish cooking properly so that we can nurture bodies, minds, and hearts. But the end product of this “collective cooking” is far from being an assured result. It is possible that the beans will turn out burnt or tasteless, or that we simply don’t reach a boiling point that allows us to become wholesome food.

This uncertainty and social apprehension bring to the surface a series of internal reactions that are often overwhelming, leading to a semi-permanent state of crisis, or even trauma. The constant bombardment of the mass media reinforces the chronic sense of overwhelm, stress, and worry.

Lea este artículo en español aquí

On a systemic scale, the incidence of Covid-19 highlights the multiple deficiencies in the functioning of consumer societies that rest on a disastrous war against nature, misunderstood as progress and economic development. Furthermore, the mitigation measures put in place to counter the spread of the virus contribute to amplify the already severe sense of disconnection and danger associated with the natural world.

In the midst of this scenario of transition and uncertainty, there’s an almost compulsive need to find an anchor or refuge to provide us a sense of security and stability—something that would end the interlude immediately and allow things to return to normal once and for all. However, the “normality” that we were accustomed to was considerably pathological and destructive. What can we do about it?

What if we take responsibility for producing the needed anchor or refuge in ourselves? And if we ask ourselves: How is it possible to connect with the fertile dimension of the crisis that we face? Or, following the previous metaphor, how can the current collective-cooking state serve as inspiration to become nutritious and tasty beans?

The intermediate view

The forced collapse of our identity connected with the slowdown of the productive mechanisms compels us, sooner or later, to come face to face with ourselves. This inward look usually characterizes the interludes found in places as diverse as ancient rites of passage, in the adventure of biological birth and the process of death, in the natural world, and in initiations of a spiritual and religious nature.

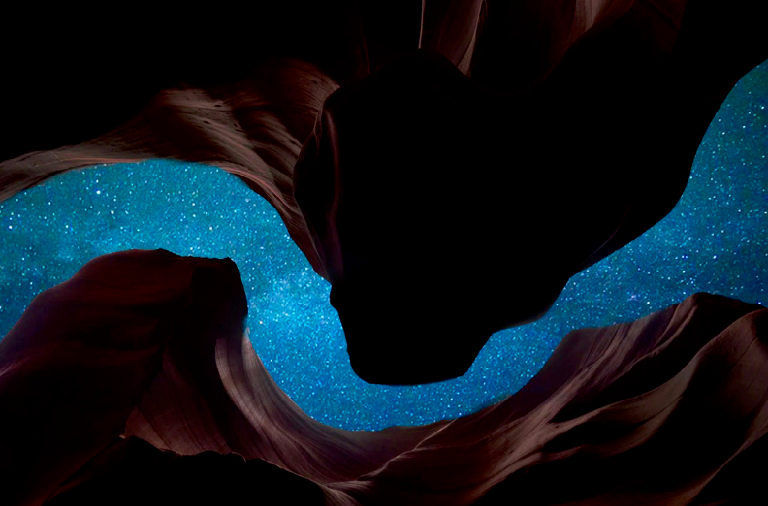

Broadly speaking, these interludes or intermediate spaces carry tremendous potential, because certainties and habitual ways of being cease to operate. Forging a healthy relationship with the uncertainty characteristic of these transitional episodes is conducive to a freedom of expression and creativity not easily found at other times. In this instance, it is useful to recognize that any process of transformation must be preceded by an intermediate state.

Tibetan Buddhism advances a refined understanding of what is surely the most fundamental transition of our lives; the step towards death. Referred to as a bardo, the interval after a human life is an exceptional opportunity to transcend the cycles of suffering and awaken to our true essence, full of plenitude, clarity, and joy. To achieve this, a lifetime of practice in the intermediate spaces is necessary. Practices include amplifying the bardo between one thought and another (a process commonly known as meditation) and bringing refined attention to the bardo between waking consciousness and deep sleep.

It is unlikely for a given person to transcend the cycle of suffering at the time of their death if they weren’t able to familiarize themselves with the nature of the bardo during their lifetime. In such a case, the individual’s consciousness experiences a series of post-mortem adventures and crossroads that lead to a new life, according to some schools of Buddhism.

A basic characteristic of training in the bardo is that the mind finds a certain degree of rest or pause from its incessant action. That is why, according to Tibetan Buddhism, the bardo of life or death works as a space where the radiant light of our essence becomes visible, and what is truly important emerges.

Re-inhabiting the bardo

The episode produced by Covid-19 represents a great pause in our daily lives, characterized by the uncertainty and potentiality of the bardo. As in every transition, in this time we are witnessing structures collapse, both mental and institutional, and the subsequent state of crisis and negotiation that this entails. Yet the bardo brings with it a valuable promise: the ability to re-create the relationship we have with ourselves and with the world.

This is a fertile time to refine our vision and choose the ways in which we wish to continue walking our paths. Today, we can choose where to direct our attention, and reformulate the principles that will oversee the rest of our precious time here on Earth. Today, we can choose to go beyond the individualism and competition of business as usual to recognize the interdependence that weaves all life, that right now knocks so clearly at the door. Today, it is possible to counteract apathy and indifference by forging an attitude of respect and reverence for other beings and for ourselves, however small our steps may be. Today, we are able to choose the path of vulnerability and courage to express what is really important to our hearts. It’s time.

The collective bardo in which we find ourselves invites us to savor the enormous fortune of having a life to live. Perhaps, one of these days, we will be able to glimpse the clear light of reality and realize that we are the beans, the fire, the water, the pot, and the cook at the same time.