Ed. note: This piece has been written in response to Valetine Moghadam’s reflection on the Great Transitions Initiative’s latest forum: Planetize the Movement!

As fate would have it, Valentine Moghadam’s essay has been overtaken by events, but it reminds us how we can be found framing today’s challenges in yesterday’s vocabulary, imagery, and paradigms. I have known Moghadam for a long time and admired her work and values. My primary concern is the outdated notions of class and the continued romanticizing of “the working class.” The failure of what we call “the Left” in the old neoliberal era was partly a failure to frame a new progressive vision.

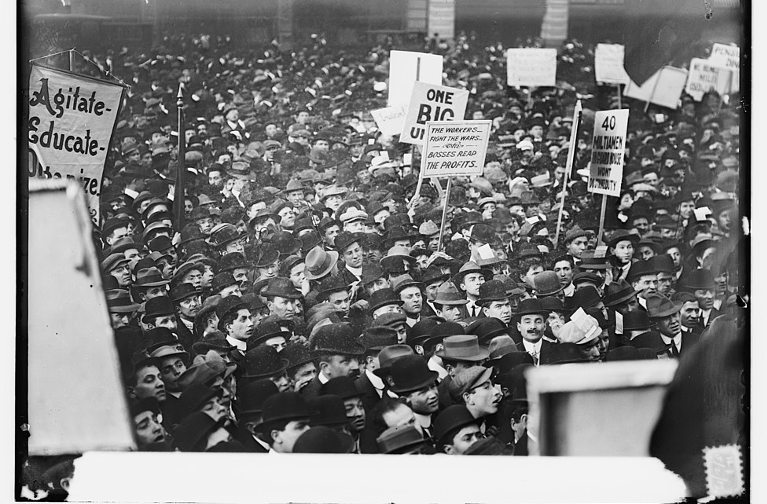

I have argued in this forum that a transformative politics must be oriented to the needs, aspirations, and dreams of the emerging mass class, not those of the old mass class. Today’s mass class is the precariat, not the proletariat. Yet many articles and tracts from the Left persist in talking romantically of ‘the working class” as synonymous with the proletariat. Ironically, the remnants of that class have become the foot-soldiers of neofascist populism.

In the recent General Election in the UK, a majority of what romantic leftists call the working class voted for the most right-wing Conservative Party in my lifetime, led by an upper-class toff known to be a serial liar. A majority of those with university degrees, particularly those in the precariat, who voted, voted for Labour. But, as with the United States, France, and elsewhere, what was striking was that most of the precariat did not vote. The Conservatives won a landslide victory with the support of just 29% of the electorate.

I saw this up close because, for the past three years, I have been an unpaid economic adviser to Shadow Chancellor John McDonnell, i.e., the person who would have become finance minister had Labour won. I wanted him to craft a vocabulary and vision to reach out to the precariat. But he was drowning in the atavistic pressures he was experiencing, from the labor unions, from social democratic think tanks, and from aging Labour MPs and Lords wedded to the imagery of the proletariat. Moghadam praises the Labour Party under Corbyn as an example of the relevance of the past language and agenda. Labour ended up obtaining the lowest share of the vote in the past century. They tried to appeal to the past, and the Conservatives outdid them.

Moghadam claims that “the moment is ripe for an alternative.” But leftists said that in 1929, and the world had its alternative in fascism. Leftists again said that in 2008, and the world got austerity and neofascist populism. The Left must always remember that a paradigm will be replaced only if another is ready and waiting to take its place. There was a lack of a progressive transformative vision out there before the pandemic hit, and the spokespeople of the institutional Left have been shockingly weak.

Val Moghadam laments the drift to populism, quite correctly. But I would like to urge her to modify her narrative in three respects. First, we are not in an era of “entrenched neoliberalism.” That was in the 1980s and 1990s. We have been in an era of entrenched rentier capitalism. Undoubtedly, the neoliberalism of the Thatcher-Reagan period, with its structural adjustment strategy in developing countries and shock therapy in the former Soviet Bloc countries, created a breeding ground for rentier capitalism, which emerged in the 1990s.

For a transformation, there must be a clear identification of what has to be overthrown and the reasons for opposing and delegitimizing it. The Left has traditionally focused on exploitation and oppression in labor. That is not where the main action is now. There has been an entrenchment of the rhetoric and reality of private property rights, from which extensive rent-seeking has been legitimized. There has been the conversion of the commons into part of the structure of rent-seeking, and the US-designed intellectual property rights regime has come to dominate global capitalism.

Movements like Occupy missed the emerging class structure in focusing on the top 1%. Extraction of rentier income is greatest in the plutocracy and for those in the elite and salariat in plutocratic corporations. Segments of the old proletariat have also gained from rentier capitalism and cannot be expected to lead a struggle to dismantle it. The main opposition will have to come from the precariat, and to some extent from quasi-peasant movements opposed to the conversion of the green and blue commons into zones of rentier capitalism.1

Second, we must deromanticize the “working class” in the old sense, and deromanticize labor unions and labor parties. Above all, we must not look back wistfully and try to rehabilitate actual communism and state socialism. Moghadam says communism was “very effective providing education,” but it was often lumpenizing, with, as we know, Lenin setting the tone in lauding Taylorism and the dehumanization of “scientific management,” in which the workers were not expected to think. Labourism was a false road.

There was a fatal loss of faith in emancipation and real freedom. There was a profound neglect of ecological values; the materialist drive saw nature as resources and the source of ‘”jobs.” Whenever there was a conflict between jobs and the conservation of the environment, labor unions and socialist labor parties opted for jobs.

This continues today. As the pandemic swept into Britain and caused an economic slump, the Trades Union Congress (TUC) and the Labour leadership rushed to advocate wage subsidies to keep people in jobs, in a scheme bound to accentuate income inequalities dramatically. Under the scheme they advocated and then supported when the Conservatives introduced it, those on the median salary were set to receive £2,000 a month, those in the precariat about £400, and those on the margins merely an extra £20. In other words, the Left advocated and supported a policy giving high-earners 100 times as much as the unemployed and five times as much as the precariat.

Third, and finally, the Left must advocate a genuinely emancipatory strategy that is driven by values of work rather than labor, and degrowth in valuing reproduction over production and fighting extinction. This is why I have long believed in having an unconditional basic income as the base of a transformative strategy. The most vehement opposition over the years has come from trade union leaders, social democrats, and certain strands of Marxists.

For me personally, the most revealing opposition was exposed at a summer school for international trade union leaders, to whom I was asked to speak about the precariat and why most in it felt alienated from trades unions. I posed the rhetorical question, “Why is it that the most vehement opposition to basic income comes from trade union leaders?”

A senior Italian unionist said, “I think it is because we think that if the workers had income security they would not join unions?” There were nods of agreement. I retorted with my best smile that this was immoral and wrong, and that secure people make braver people who are more likely to join collective bodies.

I have come to think that the themes we on the Left should be coalescing around are dismantling rentier capitalism, offering a new income distribution system in which basic income divorced from the performance of labor is the anchor, and reviving all forms of commons and commoning. Reviving the commons would be real movement, and it would be really class-based.