Ed. note: Statistics mentioned in the article were current as of April 8, 2020.

I’ve been thinking a lot about breathing, recently: how our organisms take life-supporting oxygen from Earth’s clement atmosphere, and exhale waste carbon dioxide back out. I’ve been thinking about how pleasant and normal each breath is, and about the victims of COVID-19, now dying at the rate of thousands every day, their lungs destroyed, gasping desperately for their share of breath. Breath denied.

My research is on the social science side of climate change: trying to understand how we can live better lives using less energy and natural resources. How to protect ourselves and our life support systems at the same time – and what kind of economics would allow us to do this. There are many lessons that translate to the current pandemic-induced economic crisis. Welcome to my crash course in pandenomics: the economics we need in a time of pandemic. Rather fortunately, the lessons also apply to our larger time of climate crisis – this is a revolution we must win now, but from which we will reap benefits far into the future.

Our time of need

The clash between business-as-usual economics and the pandemic demonstrates what we really need from our economy. As businesses and leisure activities grind to a halt, specific categories of jobs are protected. Work and workers we once took for granted now appear clearly as the titans underpinning our daily lives: nurses, doctors, healthcare workers in general, hospital cleaners, grocery store cashiers, stackers and delivery drivers. Somehow, stockbrokers and airline magnates failed to make the list. In a surprise twist, and despite mainstream economic narratives to the contrary, the people who keep the economy working for our survival and well-being are not at all the people who profit most from economic growth and consumerism. And this fundamental economic truth hides another one, connected to our human nature: what do we rely upon? What is it that makes us well, that allows us to live healthy and good lives?

This fundamental question is the one I ask myself in my research, as an ecological economist. What are the physical things (like energy, materials, infrastructure and so on) we need to live well? To answer it, we must understand what we truly need, and how satisfying our needs connects to well-being.

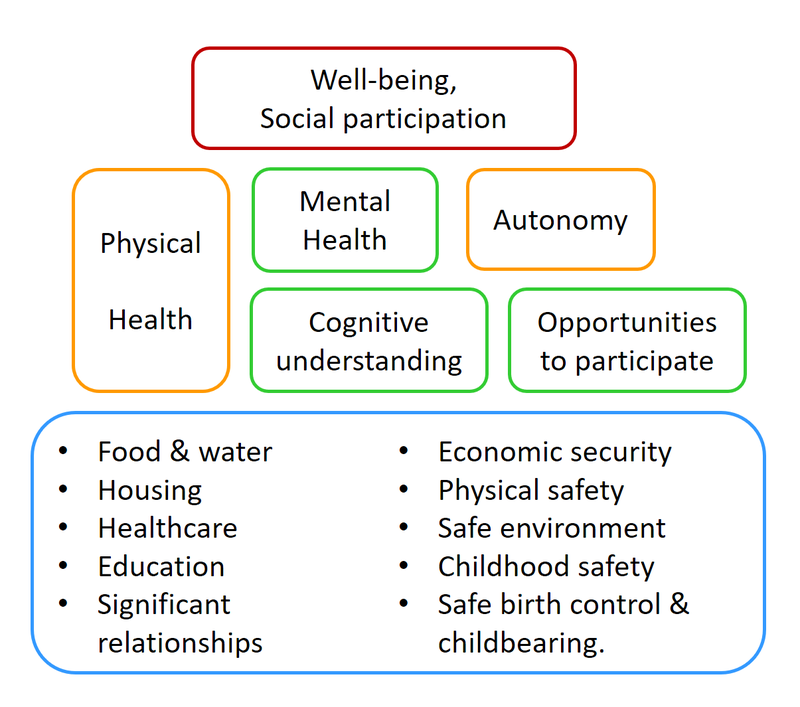

Well-being theorists Len Doyal and Ian Gough present a compelling picture of human need satisfaction: we all share a finite number of satiable and non-substitutable human needs. According to them,well-being can be understood roughly as a pyramid, with basic need satisfaction at the bottom underpinning physical, mental health and autonomy, culminating in well-being and social participation.

Human needs and well-being | Based on Doyal & Gough 1991, Gough 2015.

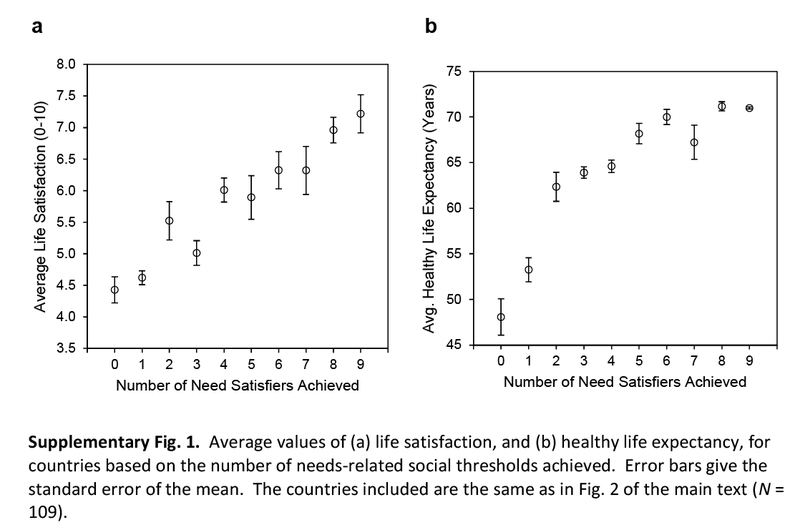

The picture put forward by Doyal & Gough might seem convincing, but can we measure it in reality? In 2018, my colleagues Dan O’Neill, Andrew Fanning, William Lamb & myself attempted to do exactly this, based on an unprecedented international dataset. We showed that well-being, measured as life satisfaction, was extraordinarily well correlated with the number of basic need thresholds that countries achieve (sufficient nutrition, sanitation, energy access, education, social support, equality, democracy, employment and income). Effectively, we confirmed Doyal & Gough’s theoretical pyramid.

International well-being correlates with the number of human needs satisfied | From O’Neill et al 2018

How is understanding well-being and human need satisfaction relevant to the coronavirus pandemic? Because it shines a spotlight on the kind of economy we need to prioritize human health. This is especially important at a time when some actors, both in academia and politics, are putting forward the claim that pausing economic activities to slow the spread of the virus will result in more harm than good (the “cure cannot be worse than the disease” argument). This argument flies in the face of the sheer deadliness of the coronavirus (alongside an overwhelmed medical system). Even worse, it is based on the incorrect assumption that economic growth underpins well-being, when robust research shows it does not.

Crucially, what is necessary for achieving well-being is the satisfaction of basic needs: not growth in consumption or economic activity. If our focus is the well-being of ourselves and other human beings, we should focus on sufficiency, rather than growth. What if things were more ominous, though, and our economic focus on growth were not just indifferent, but a deadly foe?

The crash-test dummies of exponential growth

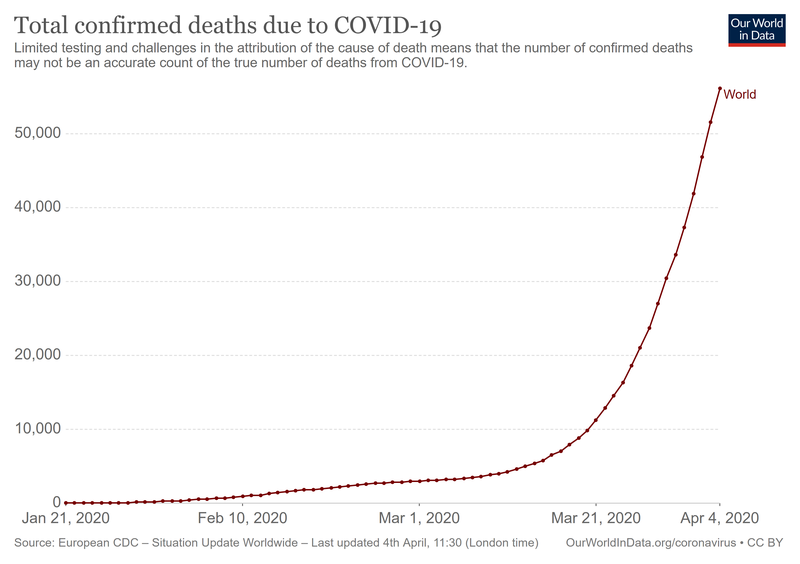

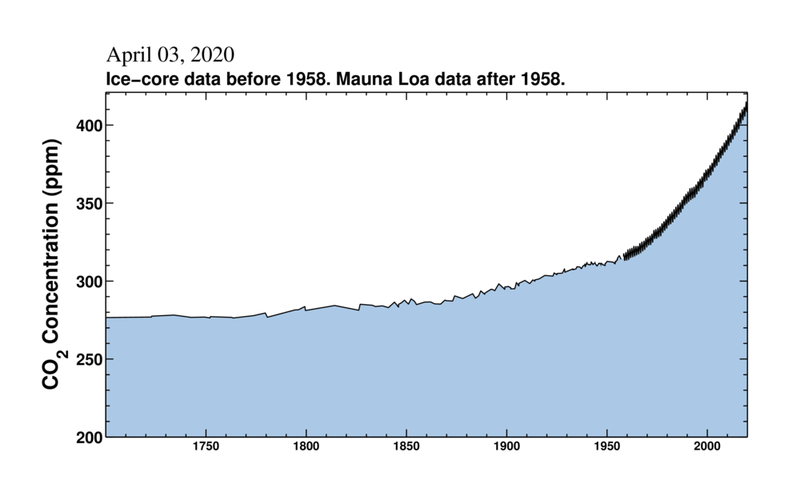

The coronavirus pandemic is giving us a unique, real-time, crash course in exponential growth – and our governments, economies and safety systems are failing the test. The supreme irony is that our economies are built on foundations of everlasting exponential monetary growth but are incapable of protecting us against the real-world exponential growth of a virus gone pandemic.

Two real-world examples of exponential growth: coronavirus deaths and carbon concentration in the atmosphere.

In fact, the growth foundations of our economy have hampered and delayed our societies’ responses to the coronavirus, enabling it to turn into a full-fledged pandemic. Coronavirus is a vastly accelerated crash test, but there is another, seemingly slower one out there, that our economies have also been dangerously failing for decades. Global warming, like coronavirus, raises the temperature and interferes with the balance of breathing, not of human bodies, but of the planet. It is a planetary-scale illness that faithfully scales with our economic exponential growth. Economic growth prevents us from acting on either climate or coronavirus, for three distinct reasons, each worth understanding and overcoming: growth as the goal, growth as governance, and growth as distraction.

Growth as the goal

The first reason our economies are growth-obsessed has to do with the international pecking order. Simply put, governments at the highest levels view their reputation as tied to the reputation of the economy. If you abandon economic growth as a policy goal, you are literally removing yourself from the club of worthwhile countries. Growth-focused governments might not be ill-intentioned – instead, they might just assume that economic growth is a good enough proxy for all the other things they might want to achieve, like social welfare or investing in action on climate, and that if they pursue growth, they are effectively pursuing all other good things. The reality could not be more different.

The growth-above-all mindset has resulted in malevolent outcomes, and these are visible every day in lack of action or ineffective action on the coronavirus pandemic. Most governments refused to enact early life-saving measures that would have prevented the arrival and spread of the coronavirus, including stopping flights, cancelling large events and closing schools and places of gathering (restaurants, bars, etc) where contagion would occur. Many governments and officials justified their refusal to take these measures on openly economic grounds, rather than public health ones, thereby making the ranking of their priorities clear for all to see: the economy above health and lives.

The past weeks have demonstrated that every necessary and vital step to protect our societies against the exponential growth of the virus has been slowed and countered by our leaders’ obsession with the exponential growth of the economy.

Growth as governance

Weighing the pandemic response against economic growth goes beyond a simple matter of moral or humanitarian priorities. Economic growth is not just a nice-to-have aspiration of our economies. If that were the case, the many laudable proposals to move away from Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and towards other indicators of social performance could have been adopted a long time ago.

It’s important to understand this: the growth aspiration of our economies is structural, built-in to the ways we run our firms and finance. The structural dependence on growth can be understood as follows: under capitalism, firms compete for market share, in order to accumulate profits. The competition imperative means they are constantly looking for ways to increase productivity. Sometimes, productivity gains are the outcome of clever innovation and efficiency – this is the part of capitalism that everyone points to when defending it. Very often, though, productivity gains are made at the expense of people (workers & consumers), planet (overexploitation of resources and pollution) and the public (avoiding regulation and taxes).

Where do profits come from, and where do they go? The Charging Bull of Wall Street photographed during the pandemic | Andrew Henkelman, CC0.

Regardless of how productivity is increased, though, the imperative of constantly increasing productivity has two main structural outcomes. First, firms tend to overproduce, leading to the necessity of persuading consumers to overconsume, through advertisement and other means. This is described masterfully by Schnaiberg and Gould’s “Treadmill of production” theory, as well as in Professor Tim Jackson’s book “Prosperity without Growth.” Second, firms tend to use financial loans to invest in productivity improvements, relying on the subsequent market expansion to allow them to repay at least part of the loans. The financial industry now pervades all aspects of our economic life (including households, firms and the public sector), demanding growth for everyday function to continue.

The structural dependency of almost every aspect of our economy on growth means that lack of growth is not just a slow day at the office: it’s a crisis. Our economies are simply not capable of dealing with lack of growth, let alone a real slowing down of the economy. Instead, they go into recessions and crises, firms go bust, workers are fired, households go hungry and are evicted.

In other words, the growth dependency of our economies is downright dangerous, especially right now, in the time of coronavirus and climate change. Facing the coronavirus requires us to hit an enormous PAUSE button on our economies, shut down, lock down, effectively go into stasis, with only essential life support functions for humans (health & food) being maintained. Interestingly, there are clear parallels with the danger from global warming. Facing the climate crisis requires us to shut down economic activities that are dependent on fossil fuels, and invest like mad in alternatives (if these exist) that are not. In both cases, the human forces within the economy that stand to lose by such changes rebel, and refuse to cooperate for the greater good.

When we try to act on either of two major public health threats, climate and coronavirus, we learn that we are governed by the forces within our societies that benefit from economic growth. We are not in democracies, where the people can decide their own fate collectively: we are in growth-ocracies, where life-saving measures are halted if they impede the accumulation of wealth through profits. Growth-as-governance is now a major obstacle to effective public health action, and its effects can be seen all around us, from our governments refusing to take early action, to their unwillingness to invest in additional hospital capacity and protective equipment, to their objection to testing medical personnel and everyday citizens, to their hesitancy in imposing meaningful lockdown.

In the United Kingdom, where I live, the growth-mania of the government has been so extreme that they sincerely convinced themselves, despite blinding evidence to the contrary, that it would be better for the country to sacrifice hundreds of thousands of citizens to coronavirus rather than impose any measure that could dent profits-as-usual. It took a combination of outraged experts, who published the estimates of likely deaths, and public outcry, for each single life-saving step to be taken. And once these steps were taken, the government’s growth mania caused it to drag its feet, and continually fail to protect its population from the economic fall-out, by enacting relief pay, rent & mortgage amnesties, protection against eviction and so on. This unwillingness to address economic hardship caused by the lockdown completely undermined the lockdown itself, with workers forced to work by venal employers, crowded together as usual in public transportation, working in unsafe proximity to other workers.

While many people under lockdown turn to online shopping, Amazon warehouse workers are not guaranteed safe working conditions | Mcwesty, CC0

Healthcare workers are being forced by the state, their employer, to work without necessary protective gear – which the state should have ordered and stocked well in advance, since they knew full well a pandemic was on the horizon. Why did our governments not prepare sufficiently, or protect us effectively now? Simply because they see investing in public health as a drain on growth.

A real crisis thus exposes growth-as-governance as misgovernance, with delayed and deadly decision-making costing lives every day, and into the future.

Growth as distraction

There is a final major way that growth-focused economies and governments harm our collective ability to respond to exponentially growing crises like the coronavirus and climate change. Growth-obsession acts as a distraction, hiding the positive alternatives we need to pursue.

The first myth to dispel is that growth is necessary or beneficial to all. To the contrary, we now know that growth accrues to the wealthiest, with scant benefits to the poor or middle class. Growth-based economies are more and more exposed as fundamentally predatory and extractive systems, with financialization (of housing, utilities, transport, basic services) acting as a key mechanism to extract revenue from everyone else, and concentrate wealth at the top.

Growth is not a panacea against poverty and deprivation, but instead dangerously distracting us from measures which would truly eliminate poverty. Examples of such measures include Universal Basic Services complemented with Universal Basic Income. Such measures rely far more on removing essential parts of the economy from the financialized treadmill (and on large wealth taxes!) than they do on eternal growth.

Another form that growth-distraction takes is market ideology, often known as neoliberalism. According to this ideology, if everyone in society acts selfishly, the invisible hand of the market will allocate resources in a way that optimizes collective welfare. As a result, our leaders are constantly to be found sitting back, selling off public assets, allowing private enterprise to profit from price-gouging and regulation-flouting, and looking over their shoulders from time to time, vaguely hoping for the cavalry of the market’s invisible collective welfare hand to ride to the rescue. Our leaders have drunk the market kool-aid to the extent where they fundamentally believe that doing nothing and enabling selfishness to flourish is the only and best way to govern. Margaret Thatcher’s TINA statement: There Is No Alternative to predatory market capitalism is carved into their very soul. For them, the only possible way to govern is by absence, rather than presence.

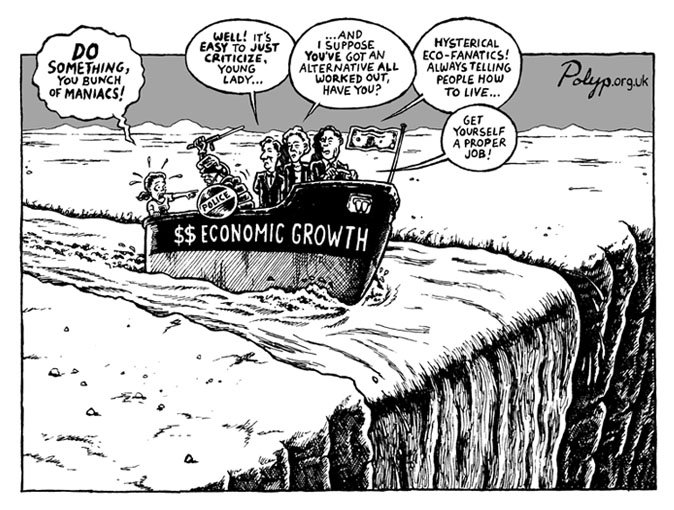

Growth distracts our leaders from addressing real problems, including coronavirus and climate | Cartoon by Polyp

The growth-focus thus robs our governments and leaders of the realization that public policy and initiative are not only possible, but that they are essential. The market will not fulfil the vital task of satisfying human needs, and enabling well-being. We have to turn away from growth-distraction, and embrace public efforts in the foundational and most important areas of our economy: healthcare (the NHS), social care, education, housing, food supply and core services such as water, energy and transport. We need governments at every level to focus on these systems and their innovation, not leave them as prey to private profit vultures.

The third way that growth-mania distracts us is with the false idea that individuals can be held responsible for social performance. This is a corollary of neoliberal market ideology, and once again it holds true for both climate and coronavirus. If the market is the solution, the individuals are the culprits: any large systemic problem has to be blamed on individual misbehaviour (not washing hands! Not recycling enough! Having carbon-intensive lifestyles!) rather than on the government or industrial activities that cause these problems in the first place.

The UK government has constantly tried to blame the failures of its abysmal coronavirus response onto its citizens – echoing the fossil fuel companies pushing the idea of personal carbon footprints to distract from their own overwhelming responsibility, or the plastics industry pushing for recycling, rather than accepting their own role in the permanent pollution of the planet. But blaming individual consumers or citizens is simply the last cruel trick in the arsenal of a growth-focused system. What we as individuals can do, however, is refuse to be fooled anymore, and demand an end to this dangerous distraction.

The rebellion of the crash-test dummies

If we are the crash-test dummies of the exponential growth of the coronavirus and carbon dioxide accumulation in the atmosphere, and if our vehicles, growth-based economies, are crashing and bursting into flames all around our ears, we should probably not be sitting there and taking it quietly. We should probably, and this is just a suggestion, mind you, take it very loudly indeed. We should rebel.

Crash test dummy | Wikimedia Commons

We first need to hold our existing governments, the drivers of the flame-wreathed vehicles, to account. This means the unquestioned focus on growth, and assumption growth is the answer to every question, must be challenged openly, and at every turn, so that our governments learn that we, at least, are no longer accepting growth-as-an-excuse from them. We can do this in every role: as citizens, activists, political party members, community groups, teachers, students. We must also support journalists and media outlets who call our governments to account, including with our financial support. Crash-test dummies should get their torches and pitchforks ready, because there should be accountability at the highest level.

Secondly, we need to support initiatives that move away from extractive, for private-profit economic growth, and in effect “growth-proof” our economies, especially its vital or foundational parts. This means moving to Universal Basic Services and/or Universal Basic Income, as well as definancializing many sectors, especially those related to basic needs, health and well-being. Supporting groups like WEAll, the Wellbeing Economy Alliance is crucial here. This means joining community groups and mutual support groups: these groups will be part of the backbone of a not-for-profit well-being economy, and this should be their ultimate goal. We should also support initiatives that refuse to use the crisis to bail our fossil fuel companies and airlines, and instead insist on “building back better,” building a new economy which is climate compatible. The call for a Green Stimulus is crucial here. Crash-test dummies should stand together and work in solidarity with each other towards a better (crash-free) world.

Third, we should refuse to be distracted by growth any longer. Growth does not serve the vast majority of the population: it accrues to the wealthy, and exacerbates inequality. Growth-at-all costs economies devour the public sector and leave it unable to face crises, such as the ongoing pandemic or the climate crisis. And finally a growth-based mentality diverts attention away from systemic understanding, preferring to shift the blame onto us as individuals. Crash-test dummies should insist that we change our economic systems, rather than feel helpless and guilty about problems we have not caused.

These are my modest proposals. Welcome to the age of pandenomics.

A post-script

This piece had to be written now, but it has no pretensions of saying the last word, it’s a stepping stone in a journey many researchers and journalists around the world are taking to figure out the keys to unlock our moment in time. It’s part of a larger effort to find a passageway, a wormhole, to a type of human society and civilization that minimizes death and destruction moving forward. I invite you to join us: not just in thought, but in action, because the struggle for a new economics is without hyperbole the fight of our lives, for our lives.

Teaser photo credit: Pandemonium by John Martin | Wikimedia Commons