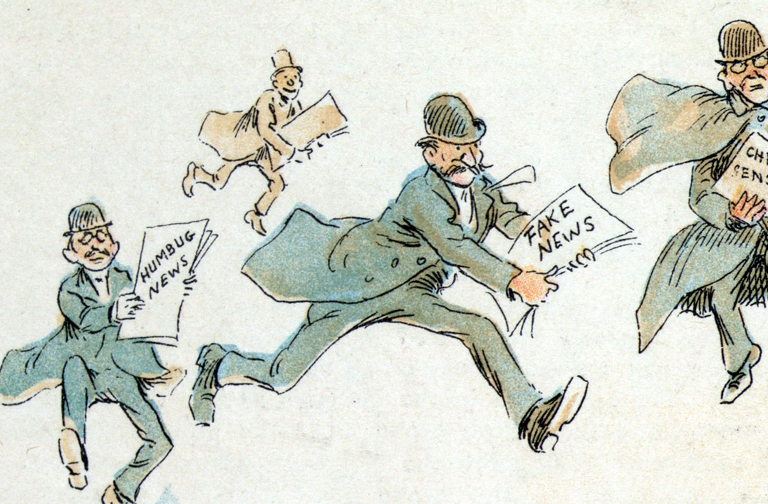

“…stopping misinformation requires social media platforms, journalists, fact checkers, and citizens all to take action”

Should media literacy be taught in schools?

That is the question an article in the Lowy Institute’s The Interpreter asks. It asks the question because media literacy is essential for navigating online media, which is where a lot of people get their news and which influences what children believe.

Alarmingly,

“…the UK Commission on Fake News and the Teaching of Critical Literacy Skills found that only 2% of children have the critical literacy skills they need to tell if a news story is real or fake”, the Interpreter article reports.

The report says that media literacy is a form of critical thinking. Now, more than ever before, critical thinking is a crucial skill needed not only by children but by the public at large. You need only look to social media to see how uncritical people can be, when they unthinkingly repost reports without knowing their origins or the motives of those who produce them.

The role of Russia’s fake news in the US election clearly demonstrated how governments use manipulative psychological tactics to interfere in the internal affairs of countries. More innocent but also potentially damaging is the inadvertent spread of fake news and misinformation by well-intentioned people who do not check whether what they repost on social media is likely to be true.

The coronavirus contagion is an example of how false information spreads rapidly online. The Eater reported that:

“The social media team at the Austin-based vodka maker — which is the top-selling spirit in America — is working overtime on Twitter today, forced to repeatedly explain that its product is not a suitable substitute for hand sanitizer — it just smells like it would be. The confusion arises amid a shortage of hand sanitizer as concerned members of the public attempt to protect against the spread of the novel coronavirus”.

Identity politics a vector for misinformation

The Interpreter article also hinted at how identity politics is a gateway to misinformation and misunderstanding. “…disinformation taps into various psychological realms, such as social identity theory and people’s sense of group belonging or social isolation”.

Participation in identity politics by uncritically adopting the values, attitudes and beliefs of a particular group can lead to hostility to and rejection of information which contradicts group assumptions and attitudes. Only information acceptable to the group is propagated within its ranks. This ‘echo chamber effect’ propagates fake news within the group even when external evidence suggests otherwise. Familiarity becomes the basis for judging the validity of statements.

How appearing to know a lot when knowing only a little spreads misinformation

We see how ready access to information produces people who believe they know a lot about a topic when they really know little. This is another gateway to personal vulnerability to fake news when the person spreads their limited knowledge, says the article.

The phenomenon has come about in part because social media manipulators weaken belief in expert opinion to sow the seeds of disbelief and further their own agendas. We see this when climate change deniers attack scientists even though the deniers have no qualifications in science. The result is a pervasive anti-expert attitude in which fake information and misinformation spreads like a contagion.

A vaccine against manipulation

In these circumstances, the article’s idea of teaching media literacy in schools makes sense. It could be a vaccine against manipulation and, also, inoculate children against advertising.

Some countries are now taking the initiative to educate children. Faktabaari teaches media literacy and fact-checking in schools in Finland. The UK may soon get its own program.

Our citizen journalism role

As media workers, we citizen journalists can play a role in discrediting fake news and media manipulation by exposing it in our work. Fact-checking websites like Snopes and others are useful, as is researching the background to stories.

You might find useful a new publication from UNESCO: Fake News’ and Disinformation: A Handbook for Journalism Education and Training. The existence of the publication highlights how fake news and the spread of misinformation and lies is affecting the public’s beliefs and attitudes.