There are times in life when we wake up and realize we no longer recognize the world around us. When life throws us such curveballs, resiliency is what determines if we sink or swim. But what is resiliency exactly, and how do we foster it?

There are times in life when we wake up and realize we no longer recognize the world around us. When life throws us such curveballs, resiliency is what determines if we sink or swim. But what is resiliency exactly, and how do we foster it?

The following excerpt is adapted from Ben Falk’s book The Resilient Farm and Homestead (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2013) and is reprinted with permission from the publisher.

I am often asked at the end of presentations a question that goes something like this: “I have limited time, money, and skill. What would be the most important things to focus on in becoming more adaptive to the changes now underway in the world?” This is a difficult question, and the answers necessarily vary by region, one’s existing skill set, the area of interest, and the physical and social context of the transitionee. However, it seems useful to at least offer an attempted distillation of answers to this question. This list, of course, is not exhaustive. It should be useful in helping us ask the right questions and begin or continue to think more clearly about our resources and what remains to learn, acquire, and develop as we attempt to become more helpful and resilient members of a rapidly changing world. The steps toward a more resilient lifestyle can be thought of in the following order and categories: Empower/Mind Shift; Root/Community; Harvest and Cycle; Shelter; Feed and Vitalize.

- Empower Yourself: Reskill and Reattitude

Master something people need, not simply what they want: food, clothing, shelter, information, tools, wellness. Remember, skills are one of the only things no one can ever take from you. Skills also tend to accrue, and many of them only accumulate over life, rather than wither. We may at times be rich or poor, socially connected or relatively alone, but for the most part our skills are ours to keep. Our attitude manifests everything else. If you don’t believe you can do something, you certainly won’t. Those who learn fast, adapt to challenges in their lives, and are generally “successful” in any way, shape, or form in this world tend to have some traits in common with each other: They believe in themselves and act from a place of confidence, not fear; they tend to treat change as an opportunity; they do not bemoan challenges or loss; they look ahead; they look practically at the future— sober in what challenges it may bring and hopeful in what opportunities may emerge. All the other steps described below to becoming useful and adaptable in the transition can be achieved with relative ease if you empower yourself in skill and in attitude.

- Establish a Land Base and a Community: Put Down Roots

After a solid skill set and adaptable attitude, land and community are the two most fundamental tools for leading a resilient life. How will you connect with a piece of land in a long-term way? What legal or other agreements will allow you to stay on that piece of land and work toward its empowering you? Who are your people? How will you find them or attract them? Do you need to change location, career, outlook, or even paradigm to find them? Do you need to lead for others to follow? These questions must be addressed and pondered, if not necessarily answered, before you can proceed to the next step.

For wanderers who think one can be highly resilient in a nomadic way, I do not mean to discount that path. It seems plausible that a group of people—not an individual—could indeed develop some level of resiliency within a nomadic lifestyle. The challenge, however, becomes one of starting from scratch every time: Unless you’re a scavenger or a raider and live on the produce of others, you need access to land to be a producer yourself (barring the truly nomadic tribe lifestyle of ages past that hunted and shepherded). So at best, the nomadic path requires one to constantly be investing in establishing relationships with new places, new people, and new land. That approach hits the reset button constantly. While the nomad is all the time reinvesting, the person who chose to set down roots is growing shoots, putting up branches toward the sky, connecting with those who have rooted around them. This does not mean that one should not be ready and willing to pick up and move if necessary, but that certainly would be a major blow to the lifestyle of one pursuing resiliency and regeneration.

- Harvest and Cycle Energy, Water, Nutrients

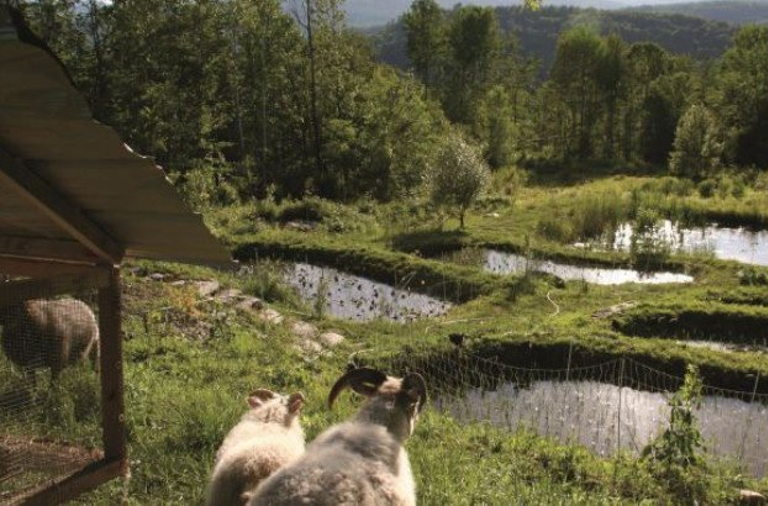

The productivity of the place you dwell is next in the order of establishing a viable lifestyle for the long haul. The land’s ability to produce is dependent upon its ability to capture sunlight, rain, snow, wind, atmosphere, and other forces and transform those forces into food, medicine, fuel, and other yields you need in a particular location. That transformation depends on sunlight’s being processed through functional water, soil, plant, fungal, and animal systems. It takes time to establish these fertility systems. Years. Best to get started now. These systems include compost, humanure, greywater, and nutrients salvaged locally. Because most other systems depend on the productivity of a site, making your place as fertile as possible should begin to happen as early as possible when you establish a home in a new place. It is this step and the following two that are the focus of much of this book.

- Develop Passive Shelter

Also at the beginning of establishing a resilient lifestyle is the need for shelter. Ensuring that this shelter goes up quickly and is as nonreliant on offsite resources as possible is a baseline part of the whole system. Keeping things simple here pays off in spades. You can always add comfort—read complexity and often expense—later. A highly functional nondependent shelter is most easily achieved if it is relatively small and very well insulated; has wood heat, gravity-fed water and a hand-pump backup; and has a cool/cold location built into it for food storage. Shelter fit for a dynamic future is fixable and adjustable by its user over the long haul.

- Learn to Cultivate and Wild-Harvest Food, Medicine, and Fuel

Food production and foraging is fundamental; so too, for an increasing number of people is the production and processing of medicine and fuel. The more self-reliant and skillful one can be with all the fundamentals of life, the more one can thrive through the period of change the world is entering. To survive and thrive in this changing future, one must be fluent with most or all of the basic production systems, including raising vegetables, foraging and hunting, animal husbandry, and growing perennial crops, such as fruits and nuts.

When Systems Fail: Emergencies and Resiliency

In my work the lines between planning a landscape and planning a lifestyle are becoming increasingly blurred. From increasing climate shifts to global economic insolvency, and the various instabilities these set in motion, sound planning for both land and lifestyle looks forward and aims to respond ahead of the curve—where response is most strategic (before the flood, before the well dries up, before the dollar tanks, before a gallon of gas is six bucks). It’s becoming increasingly clear that both our habitats (land and infrastructure) and our lifestyles (and the community they are connected to) must adapt to increasingly rapid economic, social, and political shifts that ultimately determine what ways of living will be more or less viable.

And viability or—more accurately—resiliency is what we’re after. That means responding ahead of the actual event, swinging the bat before the ball whizzes by. Responding deftly to changing conditions is at the core of successful adaptive responses in all creatures great and small on this particular planet. This holds true both for individuals and for species. To be adaptive we must extrapolate current conditions into specific future conditions that guide our planning. Since we can’t accurately predict the exact future, we must entertain diverse scenarios and plan around a selection of them—including those that present acute challenges—emergencies.

Scenario Planning and Acting

Planning for the future is greatly aided by organizing around specific events and their particular consequences—aiming to avoid the “wish I’d done that” pitfall common to generalized planning. While we cannot go through all scenarios that are worthwhile planning for, we can “mock up” some aspects of almost all of them. For instance, you can’t simulate a nuclear power plant spewing radiation into your neighborhood, but you can run a fire drill in which you do what you’d need to in such a situation: communicating with family and friends, sealing up the home and garden, potentially evacuating to a predetermined location, and so on. Only through activating these scenarios can you learn the particulars—often crucial details—that will empower a more successful response when the event is not a drill. Running event scenarios, however, takes time, and not everyone has the time or resources available to run such drills. Therefore, a combination of drills (event acting) and event planning is practical for most people to carry out as one decides what to prepare for and how.

Since we do not know which events and which particulars will come to pass, we should think through many of them; scenario planning with diverse possibilities is most helpful. Once scenarios are laid out before us, we can decide which of those are most important to actually practice around. It is most effective to start scenario planning and acting with foundational questions specific to each of our living situations. These questions are identical from location to location, but the answers vary (sometimes) with location, people involved, and other context aspects.

Scenario Mapping: Planning Questions

What events can happen globally, regionally, and locally that will impact me in significant ways? What would it mean, and what will the results be in each situation? What is currently in place in my life that can improve my ability to deal with each of these events? What aspects of my life currently present the biggest challenges to dealing with these events? Who would I turn to for help, and who would need my help in each event? What tools, equipment, skills, and other resources would be utilized in each event? And finally, what resources would most likely be lacking?

As you go through this mapping process, be sure to note, especially, all strong points and missing links or weaknesses. Write them down, and make an action plan for addressing each of these. It’s also very easy to know something is a weakness but forget to do anything about it. For instance, I always knew in the back of my mind that my lighting situation for dealing with power outages was not ideal, involving only multiple headlamps, batteries, and candles. When I did lose power a few years ago, it became apparent that the light from my Coleman Lantern was so much more helpful than candles or headlamps when a group of us gathered together to cook and eat a meal. Although I had the lantern, I did not consider it part of my lighting plan and only had a few ounces of old white gas for it. Now, I know its value and have put up a couple of sealed jugs of white gas, which, unlike gasoline, lasts a very long time, and have procured another lantern, since two is one, one is none. And one sure is useful.