The UK has just three decades to reach net-zero emissions and tree planting has emerged as a prominent part of the government’s plan to get there.

With technological solutions in their infancy, trees are for now the only scalable “negative emissions” strategy and can come with additional benefits for wildlife, flood management and health.

Moreover, there is strong public support for tree planting to tackle climate change. This was evident during the last general election, when parties competed to produce ever-more ambitious afforestation targets.

The recent budget saw new chancellor Rishi Sunak announce a forest “the size of Birmingham” across England, a contribution to the wider UK target to plant 30,000 new hectares every year.

But the apparent simplicity of planting trees to “suck” carbon from the atmosphere masks a highly complex issue. Forests are not a “silver bullet” for cutting CO2 emissions and previous drives to ramp up UK afforestation have not always gone smoothly.

The evidence is clear that even if tree planting meets its highest potential for carbon storage, it would only offset a small fraction of the UK’s current and future emissions, meaning efforts to dramatically reduce fossil fuel use should remain top priorities.

In this in-depth Q&A, Carbon Brief looks at what will be required to reach the UK’s tree-planting target, as well as the broader issues that must be addressed if forestry is to help achieve net-zero emissions.

- What is the current state of the UK’s forests?

- How will trees help reach the net-zero target by 2050?

- What kind of trees will be planted?

- Do we need to use more wood?

- Where will all the trees be planted?

- Is it possible to plant that many trees?

- Is planting new woodland the only solution?

- What new policies are required?

What is the current state of the UK’s forests?

The UK has a long history of deforestation. At the turn of the 20th century, the nation had just 5% forest cover and tree felling intensified even more during the first world war.

This prompted the creation of the Forestry Commission to buy up land for woodland expansion, which, alongside private efforts, helped to steadily expand the country’s forest.

However, even today tree cover in the UK is far lower than its closest neighbours – just 13% compared to the European average of 38%.

Current afforestation is a fraction of what it was mere decades ago, falling from a peak in the 1970s and 1980s when tax breaks fuelled extensive conifer planting. The chart below shows this decline, as well as the recent uptick in Scotland due to an improved application and funding process for new projects.

Tree planting in the UK nations from 1976-2019. Source: Forestry Commission. Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

This matters for the UK’s climate targets. Trees store carbon because they use CO2 in the process of photosynthesis to feed their growth and woodland soil is rich in organic materials, accounting for nearly 75% of the UK’s forest carbon stock.

All this means that UK forestry is a net carbon sink. The exact size of this sink recorded in the UK’s greenhouse gas inventory has shifted in recent years as new evidence has emerged but Indra Thillainathan, a land-use analyst at the Committee on Climate Change (CCC), says it currently stands at 18MtCO2e. She tells Carbon Brief:

“The land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF) inventory is subject to lots of uncertainty and has been known to vary from year to year.”

She notes that a previous adjustment from 24 to 18MtCO2e could be explained by an error that resulted in some inputs being double counted.

Whatever the exact figure, after years of declining tree-planting rates and with carbon accumulation falling as British woodlands mature, the rate of absorption is projected to fall in the coming years.

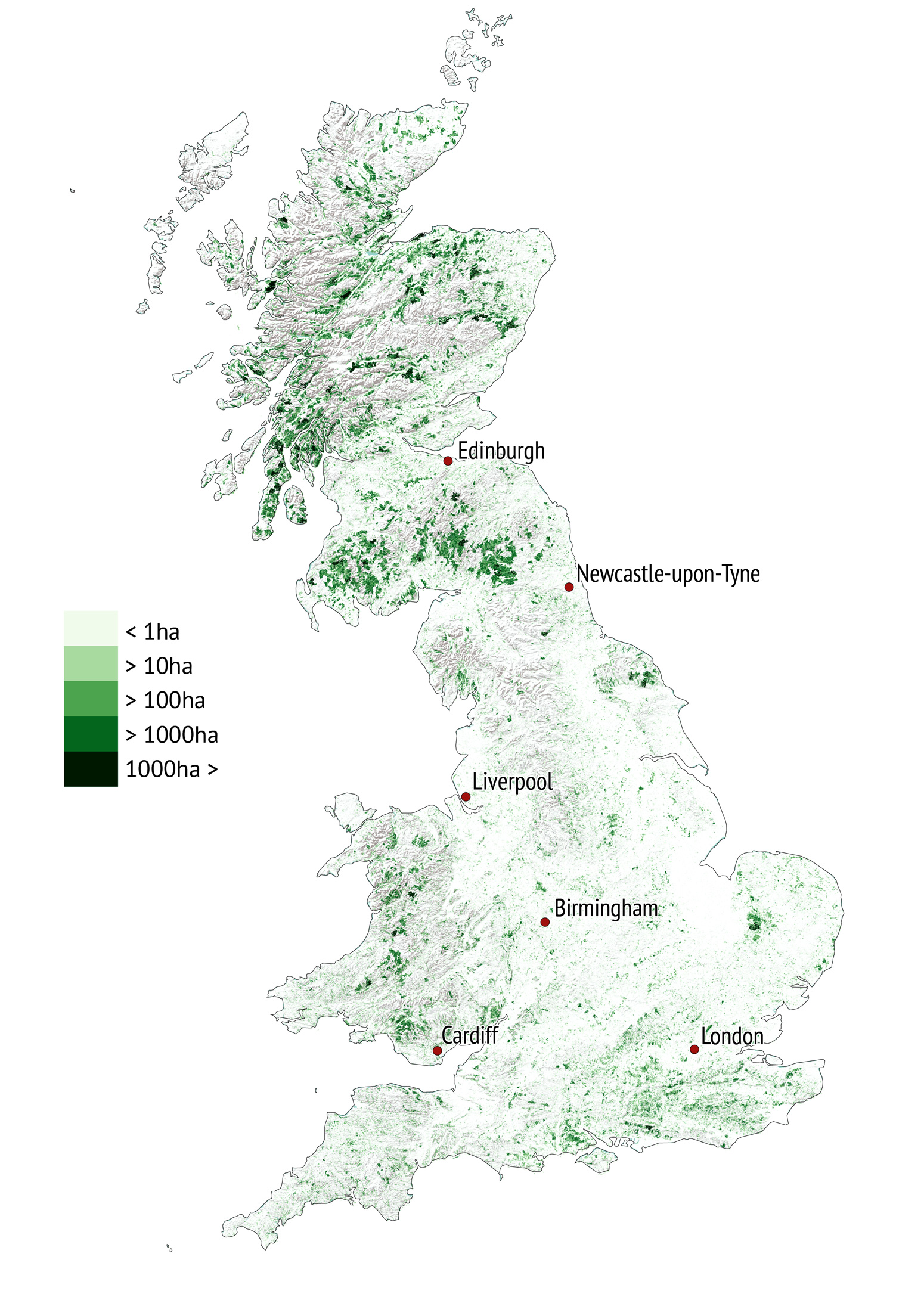

Woodland cover in Great Britain in 2018. The definition of woodland used here is a minimum area of 0.5 hectares under stands of trees with, or with the potential to achieve, tree crown cover of more than 20% of the ground. Source: National Forest Inventory. Graphic by Carbon Brief.

With climate change moving up the UK policy agenda, the last general election appeared to signal a cross-party shift in attitudes to afforestation.

However, given the country has not been on track to meet relatively low targets in recent years, Woodland Trust policy lead Andrew Allen tells Carbon Brief significant action will be necessary:

“The general election was a round of tree-planting Top Trumps – who could come up with the biggest numbers – and I’m tempted to say it was slightly divorced from reality. It’s so different from what we have done for the last two to three decades.”

The CCC’s net-zero report released last year made this clear. The government’s official climate advisory body noted that afforestation targets it had previously set for 20,000 hectares per year across the UK, which are due to increase to 27,000 by 2025, “are not being delivered, with less than 10,000 hectares planted on average over the last five years”.

The Conservatives had previously made a manifesto pledge in 2015 to plant 11m trees in England by 2020, which was subsequently adjusted to 2022. The failure to meet this “modest” target has been criticised by NGOs and the forestry sector.

Nevertheless, a Conservative election victory gave Boris Johnson’s government a mandate to pursue its target to work with the devolved administrations to “triple UK tree-planting rates to 30,000 hectares every year”. This goal was based on the CCC’s recommendation for achieving net-zero emissions by 2050.

How will trees help reach the net-zero target by 2050?

While the scientific community has pushed back against the boldest claims about the potential of tree planting for carbon sequestration, governments, businesses and the general public have largely embraced trees as an appealing climate solution.

The UK’s 30,000-hectares figure was laid out by the CCC in its net-zero report, which it said equated to planting between 90-120m trees per year.

This has since been elaborated in the committee’s net-zero land-use report. It concluded increasing forest cover to “at least 17%” of the UK’s land area, together with improved woodland management, would sequester an additional 14MtCO2e each year. This figure is based on planting 30,000 hectares annually from 2024.

In a more speculative scenario, the CCC also considers raising annual tree-planting levels to 50,000 hectares, resulting in 19% forest cover by 2050.

Based on the starting point of an 18MtCO2e forestry sink today, which was the estimated total at the time of the net-zero report, the committee calculated the 2050 sink would reach 22MtCO2e per year if their recommendations are followed. Of this, 16MtCO2 is from afforestation and 6MtCO2e from improved management of broadleaf forests.

As a comparison, under the CCC’s “business-as-usual” scenario the annual forestry net sink drops from 18 to 8MtCO2e in 2050, due to ageing woodland and low rates of planting.

Forests act as a carbon store in the landscape, but wood can also be an additional, semi-permanent store when used in construction and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). Therefore, the CCC also envisages that an additional annual 14MtCO2e could be displaced elsewhere in the economy using this harvested wood.

The government adviser also concludes that planting trees on farmland as part of agroforestry schemes “could deliver a further 6MtCO2e savings by 2050”.

The CCC commissioned the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology (CEH), which produces greenhouse gas inventories for the LULUCF sector, to generate these future estimates using a model called “C-Flow”, which was used for the inventory until 2012.

Thillainathan explains to Carbon Brief that the committee opted for this model over the “much more complicated” CARBINE model – which the centre has used for more recent inventories – to obtain a relatively simple gauge of how afforestation rates change carbon sequestration.

The CCC’s analysis was based on the planting of generalised woodlands containing representative conifer and broadleaf species, in line with UK forestry standards. Specifically, the committee opted for sitka spruce – the UK’s most popular commercially grown conifer – and beech.

Planting density is pre-allocated by the model at 3,000 trees per hectare. This number varies considerably between trees, but the CCC says 2,000-3,000 trees per hectare is a typical stocking density for new conifer forest, with the final mature yield around 300 per hectare.

The committee provided the CEH with each species’ “yield class”, a measure of tree productivity that essentially indicates how much atmospheric carbon a tree is converting into timber each year.

Finally, the CCC determined achievable tree-planting rates based on what had been achieved in the past, during the afforestation heydey of the 1970s and 1980s.

Tree planting has rapidly gained traction as a climate solution, with unlikely figures including Donald Trump and Nigel Farage getting behind it. But as with other proposed negative emissions strategies, there are concerns it could legitimise and lock in fossil fuel use as high-polluting sectors choose to rely on offsetting.

Dr Charlotte Wheeler, a forestry scientist at the University of Edinburgh, tells Carbon Brief it must not be viewed as a panacea:

“It’s being readily promoted by governments and big international organisations because it sounds very positive…but in some cases I think people are anxious that it could become a distraction from reducing fossil-fuel emissions.”

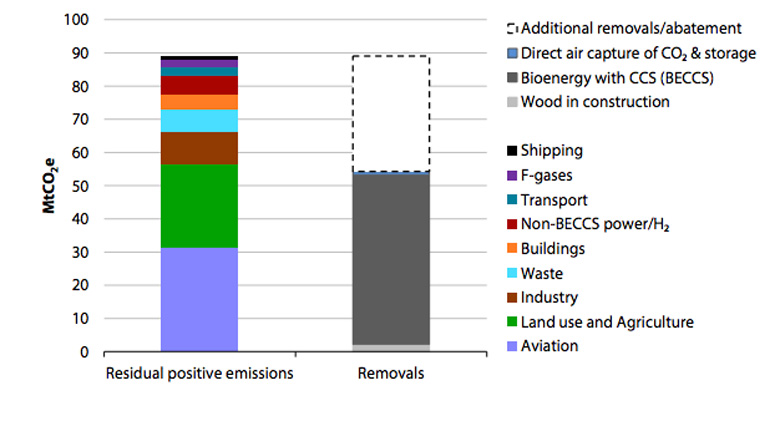

The projected 22MtCO2e sink will be important, but will only go so far. The latest UK greenhouse gas figures show emissions are 452MtCO2e and by 2050 the CCC still expects around 90MtCO2e of “residual” emissions that will have to be removed by other means.

While the CCC’s work has distilled UK tree planting down to a handful of key numbers and targets, their first land-use report, released at the start of 2018, made it clear there are major challenges ahead:

“Meeting these planting rates would require significant scaling up across the sector, from research into the most appropriate species to plant across the country, scaling up the nursery sector to grow the saplings, to actual planting on site.”

Moreover, with the clock ticking on the 2050 target, it is important that afforestation is well thought out. Otherwise, well-meaning efforts could be ineffective or even undermine the target. For example, if the wrong species or locations are chosen, as Wheeler tells Carbon Brief:

“You actually really need to pay attention to some of these things because if you don’t you could end up promoting and investing a lot of money in a scheme that actually might not have an enormous net benefit in terms of its carbon stocks.”

What kind of trees will be planted?

A vast tree-planting campaign does not necessarily mean miles of untamed woodlands. The reality is that 83% of UK forests are managed for production purposes.

Whatever the function of the woodland, from a purely climate perspective the only aspect that should matter is carbon uptake. This varies significantly between tree species, but establishing which varieties are best to plant is not straightforward.

At the most basic level, there is a divide between conifers and broadleaves when it comes to carbon sequestration. As a rule, the conifers preferred by timber producers are faster growing and, therefore, absorb a lot of carbon quickly.

This is exemplified by sitka spruce, a non-native species that makes up more than half of the UK’s commercial conifer plantations and is also the representative conifer species in CCC modelling.

Dr Eleanor Harris, policy researcher at trade association the Confederation of Forest Industries (Confor), tells Carbon Brief these trees are a key species for the 2050 target:

“If you want carbon in the next 30 years and you are starting from scratch, there’s no contest. Sitka has been bred to convert atmospheric carbon into wood.”

Sitka spruce has a very high yield class (YC). This is a measure used in UK forestry to gauge the productivity of trees and it can, therefore, also be used, as the CCC does, as an indicator of how much carbon they are absorbing.

As yield class is based on the annual volume of timber being added by a tree on a particular site under specific conditions, each species can have a range of values.

However, broadleaves generally grow with a YC of between 4-8, meaning they grow 4-8 cubic metres per hectare per year. Oak grows at around 6, wild cherry at 8 and poplar achieving rates of up to 12.

By contrast, the industry average for sitka spruce is considered to be around 16. Harris says it is not unheard of for stands of sitka to reach as high as 44.

(In its modelling, the CCC assumes YC13 for conifers and YC7 for broadleaves. Thillainathan tells Carbon Brief that as the CCC prepares its sixth carbon budget advice, due later this year, it is likely it will increase the YC used for sitka spruce.)

The chart below shows that by the 2050 net-zero deadline, a conifer plantation made up mainly of YC20 sitka spruce would sequester more carbon than a native broadleaf plantation with YC6.

Carbon sequestration up until the 2050 net-zero deadline in a conifer (dark) and broadleaf (light) stand of trees. This chart is based on 50-hectare plantations, one made up of conifers planted to the UK Forestry Standard (75% sitka spruce at yield class 20, 10% Douglas fir and Scots pine, 5% native broadleaves, 10% open space), and one a native broadleaf scheme with yield class 6 (90% broadleaves, 10% open space). Both assume no thinning or felling has taken place. Source: Forest Carbon, based on Woodland Carbon Code lookup tables. Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

Despite their high productivity, however, vast plantations of sitka spruce may not be the best solution, even if carbon is the only priority taken into account.

A report by centre-right thinktank Policy Exchange last year warned that the 2050 net-zero target might distort policy in favour of quantity over quality in woodlands.

In fact, extensive research has demonstrated that diverse forests are actually better at sequestering carbon, as well as providing more biodiverse habitats and greater resilience to diseases, pests and climate change.

While the Woodland Trust’s Andrew Allen says sitka spruce is “absolutely part of the solution”, he emphasises the need for other varieties, including broadleaves and native species.

Conifers were the dominant trees being planted in the UK until the 1988 budget (grey area in the chart, below). Then-chancellor – and prominent climate sceptic – Nigel Lawson, removed beneficial tax breaks for afforestation, partly in response to a backlash against harmful planting of conifer monocultures in Scotland’s Flow Country.

There was then a surge in enthusiasm for broadleaf planting (orange), partly paid for with early forms of carbon offsetting, before renewed interest in planting for timber in Scotland drove a recent uptick. These trends can be seen in the chart below.

Tree planting between 1976-2019 by variety of tree. The rate of conifer planting (dark) dropped off in the 1990s and has only recently recovered in Scotland, while broadleaf planting (light) has become more popular. Source: Forestry Commission. Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

The CCC’s 2050 pathway is based on a woodland creation split of 60:40 broadleaf to conifers. The CCC noted that “planting requires both productive conifers and standing broadleaved woodland”.

Broadleaves may grow slower, but a species such as oak can ultimately lock more carbon into its dense wood than softwood species, such as sitka spruce. As they tend to be left to grow, they will continue absorbing carbon for decades after commercial conifers have sprung up and been harvested.

In its “emergency tree plan”, the Woodland Trust states “the majority of tree cover expansion should be delivered with native woods and trees, due to the importance of tackling the nature and climate crises together”.

Dr James Morison, who leads the climate change science group at Forest Research, the scientific division of the Forestry Commission, says even if considering carbon storage in isolation there are no simple answers. An often-quoted phrase in the sector is “the right tree in the right place”, as the growth rate of any species is influenced by factors including soil type and local climate.

Moreover, focusing on productivity as a measure of carbon sequestration comes with problems, as Morison tells Carbon Brief:

“If we are thinking of fastest growth, a forester will probably think of volume [of timber], but the rest of the tree – which can be 50% or more of the tree – is also important. It’s not just the volume of the timber stem and so on. Actually, the carbon density varies a lot.”

The need for diversity in afforestation is reflected, to an extent, in the UK Forestry Standard, which has guided tree planting since 1998. It states that within new woodland “a maximum of 75% may be allocated to a single species”, with 10% for other species, 5% for “native broadleaved trees or shrubs” and 10% for open ground or conservation areas.

Prof Nathalie Seddon, a biodiversity scientist at the University of Oxford, says while such standards are welcome “it seems like we are going back to the 1980s”, with current planting trends focusing on productive conifers. She tells Carbon Brief:

“Even if your primary objective is carbon storage, which as a caveat is extremely dangerous thing to do because you end up compromising the other vital things that ecosystems do…that carbon storage is not going to be resilient in a rapidly changing world if it’s in a monoculture or a low-diversity plantation.”

There are already efforts (pdf) to increase the genetic diversity of forests by incorporating trees from southern latitudes and, in doing so, increase resilience to future warmer, dryer conditions.

Morison says this is part of wider efforts to guide tree planting based on how climate change is expected to affect the UK. Forest Research has incorporated this guidance into its toolkit for advising landowners on the best trees to plant in their locations.

Outgoing Forestry Commission chair Sir Harry Studholme has also stated foreign species could help provide resilience against climate change.

Ironically, beech, the species used to represent broadleaf trees in the CCC’s modelling, is likely to be one of the British species most threatened by drier conditions in the near future.

Do we need to use more wood?

Forests are not permanent stores of carbon. Even without human intervention, there is a natural flow of CO2 in and out of woodlands as trees grow and die.

Harvesting trees reduces the carbon stored in the forest even more. Despite this, there are clear benefits to a well-developed timber sector, which could drive the creation of new forest by making it an appealing business prospect.

As the chart below shows, most afforestation since the 1980s has been carried out by the private sector. Government bodies, such as the Forestry Commission and its equivalents in the devolved administrations, decided around this time it was more cost-effective to pay private landowners grants per hectare than to buy the land and plant it themselves.

Tree planting in the UK between 1976-2019, hectares, by type of organisation. The private sector (light) has dominated over public planting (dark) since the 1980s. Source: Forestry Commission. Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

In an ideal situation, besides creating a large store of carbon in the landscape, wood production can also create another store in the products being made.

“You’re not just creating a forest, you’re actually creating the materials that will decarbonise the economy,” Confor’s Eleanor Harris tells Carbon Brief, noting the potential of British wood to replace concrete and plastic, and drive down the overexploitation of woodlands overseas.

As it stands, the relatively young British timber industry, largely based on conifers such as sitka spruce, is a long way from this idealised view.

The UK is one of the largest net importers of forest products by value in the world, second only to China. In total, 80% of the nation’s wood is imported.

There are also issues with the uses that wood products are being put to. From a carbon accounting perspective, there is a considerable difference between wood used in construction, which may last a century, and wood used in fencing, which may last 15 years.

The CCC envisages wood being used to produce low-emissions energy, as bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), or in construction. Andrew Allen from the Woodland Trust tells Carbon Brief this is not what is currently happening:

“At the moment, we reckon only 20% of the sitka spruce grown in this country ends up in things like construction, so actually holds its carbon in the long term. A lot of it ends up in things like fence panels and palettes, which with the best will in the world are either rotting away or burnt within 10-15 years, releasing all the carbon.”

In 2018, at least half of UK-grown wood was being used in relatively short-term applications, such as panelling, fencing and pulp. A further quarter was being burned for energy.

This is highlighted in a report produced for the RSPB, which points out that the climate benefits of fast-growing conifers will be rendered useless if their products are releasing carbon straight back into the atmosphere.

Even so, the Woodland Trust and other pro-afforestation NGOs agree that a strong timber sector can still be a crucial component in tackling climate change.

In a Policy Exchange report titled “Bigger, Better Forests”, the thinktank calls for an overhaul of the UK’s forestry sector to drive the uptake of timber in construction. It states that, compared to masonry, concrete and steel, timber can reduce a building’s “embodied carbon” by between 20-60%.

Therefore, it recommends various policies to expand the sector, including a drive to expand the UK broadleaf timber sector, something the government itself has also alluded to. The report also calls for a carbon tax on the embodied carbon in new buildings to encourage a switch to timber.

Incorporating more wood into construction certainly appears to be a win-win, especially considering its cost which is roughly equivalent to similar building materials – and it is being pushed by the forestry industry as a good argument for productive conifer plantations.

Greenhouse gas removals needed to balance remaining positive emissions in 2050, according to the Committee on Climate Change. Source: CCC analysis from net-zero report.

This fairly small saving is based on the advisers’ more ambitious scenario in which 40% of houses and flats are built with wooden frames, up from 30% now. The vast majority of the 14MtCO2e savings from harvested materials are expected to come from BECCS.

More broadly, the RSPB report states that estimates of the capacity for harvested wood products to displace carbon-intensive materials, such as steel, varies widely, with some authors finding that “commonly cited figures are gross over-estimates”.

Similarly, while burning wood for fuel without carbon capture can be viewed as an effective way of displacing fossil fuels, the report argues that the time it takes for those emissions to be reabsorbed means it should not be viewed as carbon neutral.

The CCC has established a hierarchy of how biomass should be used by 2050, with wood use in construction at the top, followed by BECCS, and burning it for power towards the bottom.

Where will all the trees be planted?

The CCC’s target for 30,000-50,000 hectares a year from 2024 amounts to 0.9m-1.5m hectares of new woodland planted by 2050, raising forest cover to 17%, up from 13% today. A top priority for UK forestry in the coming years will be identifying space for these trees.

Doing so will inevitably result in compromises, as the competing needs of agriculture, wildlife and the general public are balanced. However, there have been attempts to identify areas more amenable to tree planting.

Unpublished Forestry Commission analysis has identified 3.2m hectares of “low-sensitive” areas for planting trees in England alone.

These so-called “low risk areas for woodland creation” include lower quality agricultural land and other areas that are a considerable distance away from sites for biodiversity and conservation.

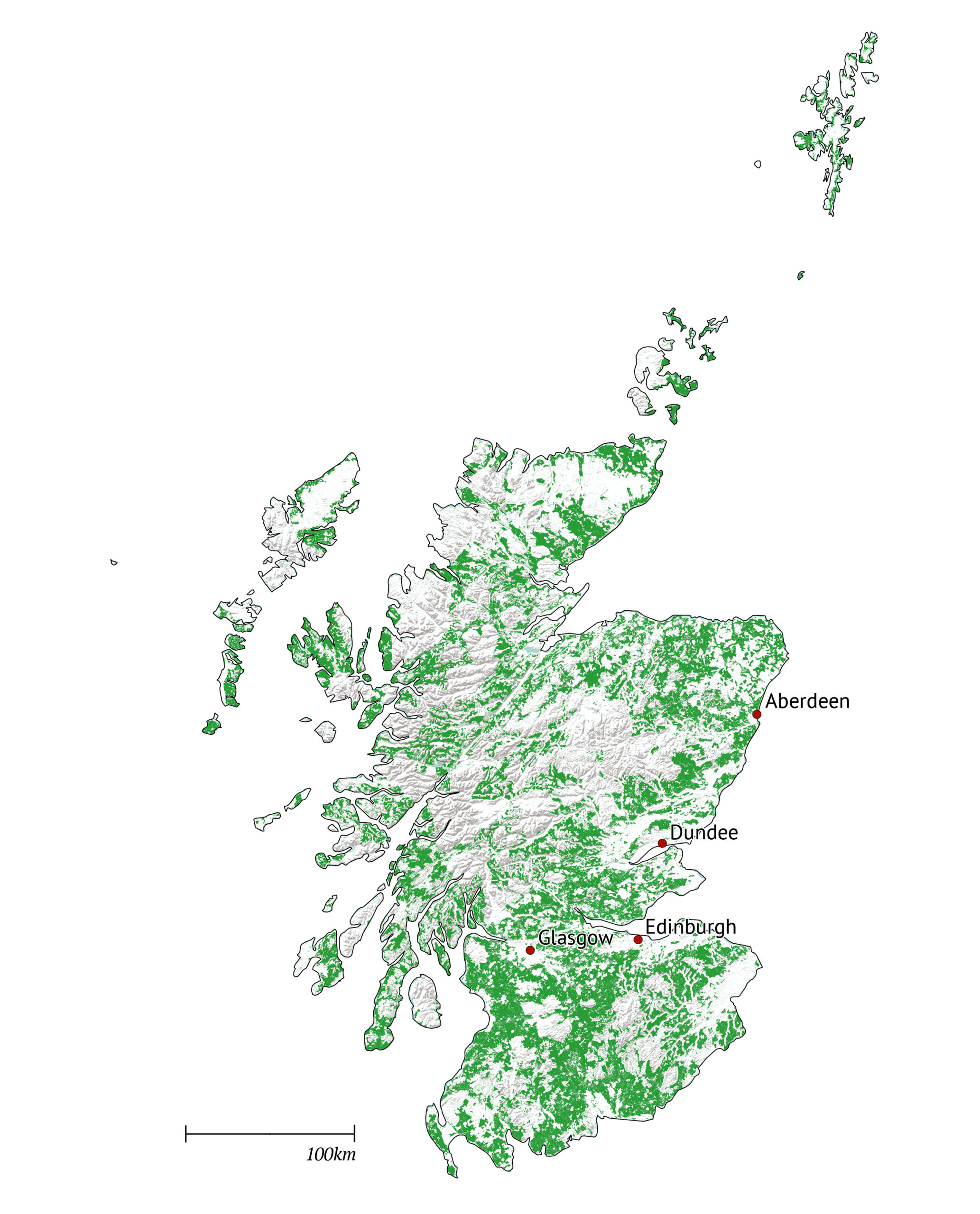

Similar analysis undertaken for the Scottish government in 2012 identified an additional 2.7m hectares, roughly a third of the country, that has potential for woodland expansion. This area can be seen in the map below.

While this work represents a broad-brush approach to the issue and does not necessarily recommend these areas as specific targets for afforestation, it does give a sense of the available space within the UK.

It also shows that woodland expansion could easily be accommodated within areas identified as “low-sensitive”, without needing to plant trees elsewhere.

Map showing land in Scotland “most likely to have potential for woodland expansion” (green) in 2012, based on a three tiered approach developed by the James Hutton Institute and Forest Research for Scottish government. They identified 2.69m hectares (representing 34% of Scotland), taking into account the quality of land for agriculture, its suitability for woodland, the presence of priority habitats and the presence of deep peat which is unsuitable for woodland creation. Source: Woodland Expansion Advisory Group. Graphic by Carbon Brief.

Tree planting is not expected to be spread evenly across the UK. Prior to the focus on net-zero, the government’s 25-year environment plan set a target of planting 180,000 hectares in England by end of 2042, though last year the nation missed its annual target of 5,000 hectares.

The Scottish government’s annual planting target is 10,000 hectares, with the goal of increasing this to 15,000 hectares by 2025 and even 18,000 hectares by 2030.

This reflects key differences that also play out on a regional scale. Broadly speaking Scotland has more low-quality agricultural land than England, which makes it more appealing for afforestation.

Wales has set a target of 2,000 hectares per year between 2020 and 2030, although the CCC has recommended it should aim for 4,000 hectares per year (roughly what it has achieved in the past decade).

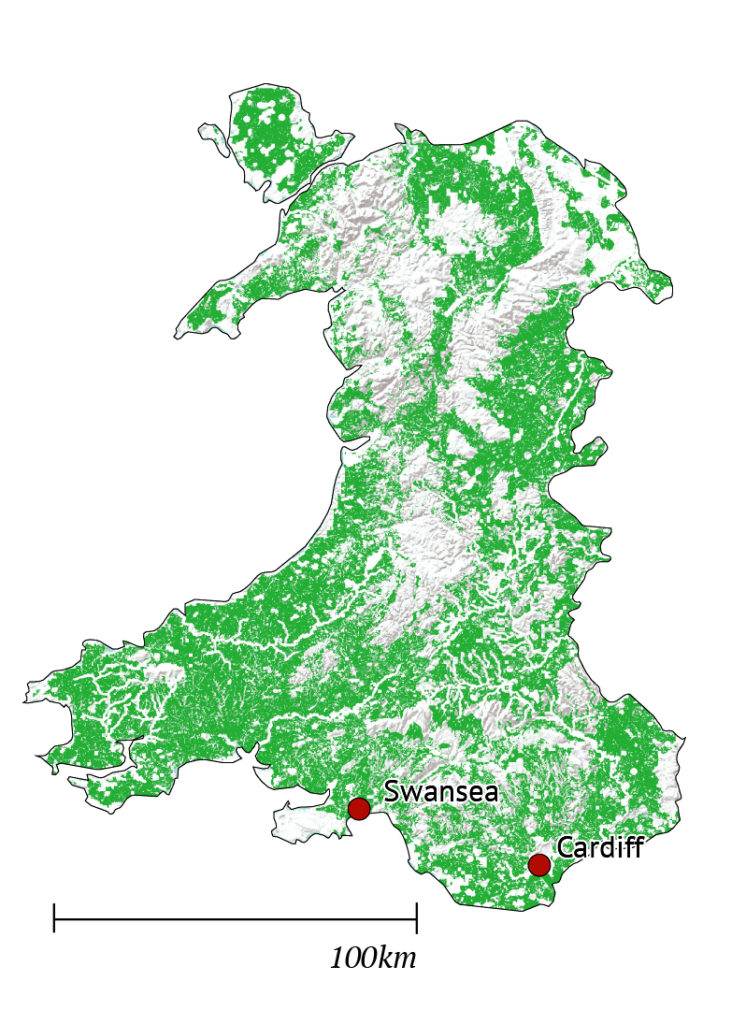

The Welsh government’s Glastir programme has graded areas of the country’s landscape to identify possible tree-planting locations. A simplified version of the resulting map can be seen below.

Map showing potential opportunities in Wales (green) for afforestation and reforestation through the Welsh Government’s Glastir programme to contribute to their target of 2,000 hectares of new woodland per annum. Sensitive areas to woodland creation, such as areas of deep peat, or scheduled ancient monuments, are coloured grey, although there may still be possibilities for woodland creation there. Unlike the data for England and Scotland, in the original dataset (which can be viewed here) the green area includes a range of suitabilities for tree planting, with darker tones indicating greater suitability. The map does not constitute a statement of where Welsh Government will be planting. Source: Welsh Government. Graphic by Carbon Brief.

Northern Ireland, the least forested nation in the UK, has a more modest target of 9,000 hectares of new woodland by 2030, or 900 every year, in line with CCC recommendations. Taken together these pledges still fall short of the 30,000 figures required under the CCC’s ambitious scenario.

Ted Wilson from Silviculture Research International tells Carbon Brief that while there is “plenty of land” in the UK to achieve the government’s targets, the main issue is accessing this land and incentivising landowners to make the switch to forestry.

As around 70% of the UK’s land area is farmland, it seems inevitable that some of this would need to be converted to woodland, particularly lower quality pastures for grazing livestock.

Indeed, the CCC concluded in its most recent land-use report that 22% of agricultural land must be turned over to carbon sequestration if the net-zero goal is to be achieved. This would include peatland restoration and energy crops, as well as afforestation.

In this scenario, the committee said farmland would be released as a result of reductions in meat and dairy consumption, increased farm efficiency and reduced food waste, all while maintaining UK food production and not increasing imports.

However, persuading farmers to become foresters will require policies that can overcome the “deep cultural divide” that many feel has emerged between the two sectors (see the next section for discussion of policies).

This divide is reflected in the National Farmers Union (NFU) net-zero strategy, which places a lower emphasis on tree planting than the CCC’s strategy, estimating woodlands planted on farms could deliver savings of 0.7MtCO2e by 2040.

The NFU’s climate change adviser Dr Jonathan Scurlock tells Carbon Brief the union does not accept that reducing agricultural areas should be an “explicit goal” of climate policy, although they accept that market forces may drive things that way:

“[The CCC] believes a very substantial increase in forest and woodland cover is achievable. But we do have our doubts…you’re going to need really significant intervention to drive land-use change in terms of making a business case for long-term permanent woodland on agricultural land.”

If landowners are incentivised to plant trees, the next concern will be how to ensure they are planting them in locations that can maximise carbon uptake.

This includes accounting for the carbon that is already stored at a site prior to woodland growth. “You can’t just assume that where you’re planting has nothing there already,” Dr Charlotte Wheeler tells Carbon Brief.

A historic example of such mismanagement was the conversion of peatland in Scotland’s Flow Country into conifer monocultures between the 1950s and 1980s, with harmful effects (pdf) for local wildlife and carbon storage. The CCC’s Indra Thillainathan says this particular issue is reflected in its scenarios:

“We constrain future planting [in our modelling] to ensure that it is not being planted on deep peat. However, some planting does happen on shallower peat with the exception of priority habitat, protected landscapes, above the moorline or SSSIs/SACs/SPAs.”

She notes that this is consistent with the UK Forestry Standard, which sets minimum standards for sustainability and will govern future tree planting.

However, the RSPB has suggested this standard does not provide sufficient protection for biodiversity and may push tree planting into areas that threaten vulnerable species. The Woodland Trust recently faced an outcry over a patch of trees that had been planted on a rare wildflower meadow.

Andrew Allen notes that with so many different factors for landowners to take into consideration – not only carbon and biodiversity but also flood alleviation and public access – there is a need for high-level guidance and mapping of which areas should be targeted for tree planting.

“I think it’s fair to say there is a gap at the really large scale, landscape planning area,” Dr James Morison from Forest Research tells Carbon Brief, noting that the various English agencies are currently discussing how best to join up their activities.

Finally, afforestation projects must take the future climate into consideration. A report compiled by consultancy Environment System Ltd (Envsys) for the CCC found that under a “medium” emissions scenario, the area of land classed as “suitable” for oak trees falls from 12% of the UK’s land to 9% by 2050. Such outcomes could mean less suitable land has to be utilised for tree planting, or other species used instead.

Is it possible to plant that many trees?

Upon the release of its latest report on land use, CCC chief executive Chris Stark said their recommendations for an uptick in afforestation meant it was “a good time to be a silviculturist”.

However, around the general election there was much speculation in the media about whether the various tree-planting proposals on offer would be feasible. Fact-checking organisation FullFact noted Labour’s pledge in particular “ruffled a few leaves”.

While large-scale tree planting is possible, there are many practical obstacles that will need to be overcome to achieve the CCC and government targets for tree planting in the UK.

Many working in the sector warn that decades of underinvestment, particularly outside Scotland, mean there is a lack of infrastructure, expertise and workforce. “[There’s] this idea that we can just magic up enough trees for 20-30,000 hectares of planting a year, and we just can’t,” says the Woodland Trust’s Andrew Allen.

Trees are initially grown from seeds in nurseries, and the UK’s nurseries are currently not able to produce new plants in the quantities required.

Allen says that while it is difficult to gauge exact numbers, a “significant proportion” of the trees planted in this country are imported from the continent.

This is especially concerning given the threats posed by imported diseases, such as ash dieback, which was brought from mainland Europe around 30 years ago and is expected to kill up to 95% of the UK’s ash trees.

Nurseries must be able to make predictions around three years in advance and, therefore, will not be able to invest in capacity building without stability. In the past, nursery managers have been forced to burn their young trees when demand vanished due to shifts in subsidies.

There are also concerns about who will plant all of the trees. A 2017 report by the Royal Forestry Society (RFS) identified skills shortages and declining enrolment in forestry courses at UK institutions.

While a skilled individual can plant thousands of trees in a day, a recent BBC News report highlighted the lack of expertise in the UK, with many tree planters coming from Canada, Australia and Eastern Europe.

This issue “will only be exacerbated” by the net-zero planting target, RFS chief executive Simon Lloyd tells Carbon Brief:

“To do this will require more researchers, silviculturists, ecologists, planting, maintenance and harvesting contractors. It will also require a huge retraining of land managers who lack knowledge and understanding of woodland management.”

Silviculturist Ted Wilson says the sector has been further dented by cuts to research funding, such as the 25% reduction for the Forestry Commission in 2011. He says the situation has improved slightly in more recent years, but the majority of spending is on tree health issues:

“We need to have a significant increase in funding for forest research and especially a commitment to long-term research studies in silviculture, tree genetics and forest resilience to environmental threats.”

Of the devolved administrations, Scotland has been recognised for recent efforts to boost its forestry sector, which could serve as a model for the other nations.

Applying to plant trees can be complicated, according to Confor’s Eleanor Harris. She says the Scottish government has restructured its application process to simplify matters and supplied sufficient grants as well.

“Land came forward, farmers started coming forward,” she says, resulting in the announcement last year that Scotland had, according to the Scottish government, “smashed” its tree-planting target, the only part of the UK to do so.

Is planting new woodland the only solution?

While finding new land to plant trees on can throw up various complications, there are large areas of forest across the UK that are currently not meeting their carbon storing potential.

The vast majority of the UK’s broadleaf forests are currently unmanaged or at least undermanaged. These stands are often damaged by deer or squirrels, or afflicted with disease.

These trees are not being grown for timber and their lack of economic value means landowners are often unwilling to invest in them.

If 80% of the UK’s broadleaf forests were brought into active management that is compliant with the UK Forestry Standard, the CCC projects that significant carbon savings would result. In fact, around a third of the 2050 carbon sink is expected to result from improved management.

It also says that if the initial cost barriers can be overcome there are financial benefits to bringing these woodlands under management.

Management can help younger and better quality trees to thrive, which can promote carbon storage and also resilience, which avoids carbon losses from dead trees. Moreover, these trees do not require land being freed up from other uses.

Nevertheless, according to Confor’s Eleanor Harris: “it’s a bit of a hard sell because politicians want hectares of new woodland”.

Another alternative to planting trees is simply allowing nature to take its course, a strategy which Prof Nathalie Seddon says “ends up producing ecosystems with fewer trade-offs”.

Richard Bunting from Rewilding Britain emphasises the importance of “first and foremost, protecting what we have got and expanding it” over tree planting:

“Natural regeneration is going to be slower to accumulate carbon in tree biomass than planting trees, but we think they are both really important because of the ecological benefits of regeneration.”

Rewilding Britain’s report on this topic, “Rewilding and Climate Breakdown”, examined the potential for naturally regenerating forest to absorb carbon. It notes that such forests are likely to absorb around 2.4 tonnes of carbon/hectare/year by 2050, ultimately rising to 4.1.

By way of comparison, the report states the maximum sequestration rate for fast-growing lowland British forests are between 6-10 tonnes/hectare/year. This tallies with a long-term case study for Confor which finds a 75% sitka spruce forest absorbs 7.3.

(These figures are not the same as yield class, which is used to indicate the productivity or the amount of timber produced.)

Seddon also notes that when land is allowed to revert to functioning ecosystems, culling of squirrels, rabbits and deer – recently advocated by the new Forestry Commission chair Sir William Worsley – is less likely to be needed.

To promote nature-based carbon sequestration, Rewilding Britain suggests the introduction of a carbon price payable per hectare. It says despite the slower rate of carbon sequestration, this price should stay the same for naturally regenerated land to account for ecological benefits “such as minimised disturbance to the ground”.

The group suggests such payments should also be made to managers of old-growth native forests to remove “perverse incentives” to deforest and then restore those areas.

Following the announcement that Alok Sharma had been appointed president of this year’s COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, a group of research organisations and NGOs wrote an open letter calling on him to recognise the value of these kinds of “nature-based solutions” to climate change.

What new policies are required?

There is general agreement that if the UK government is going to effectively triple the national rate of tree planting, a primary concern will be convincing landowners to turn their land over to forestry in large enough numbers.

There are various barriers that can prevent farmers, who are used to working with food crops and livestock, from throwing their lot in with forestry.

Forests are currently supported with grants to cover their startup costs, after which landowners will not see a payout for a few decades, beyond some initial maintenance grants and money from “thinnings” as they remove smaller, weaker trees.

There are technical considerations, such as how to plant trees that are suitable for the location and abide by the UK Forestry Standard, which requires special expertise. Roughly a quarter of land area in Great Britain is run by tenant farmers, who may be banned from using their land for alternative purposes.

Crucially, there is also the concept of “permanence” which is embedded in UK forestry, as the NFU’s Dr Jonathan Scurlock tells Carbon Brief:

“The problem with the Forestry Act is that it means all the land valuers and land agents who buy and sell agricultural land see a permanent decrease in the capital value of land if it is put into permanent woodland, because it is very difficult to reverse it.”

When land is covered in trees, if those trees are subsequently removed the owner is obliged to replant them. According to Scurlock, this permanence is a deterrent for farmers who are used to working under more flexible models.

He says they are far more likely to embrace climate beneficial measures, such as growing energy crops, or even planting isolated stands of trees, as long as there is the future possibility the land could be returned to other uses.

Moreover, parliament’s Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee has described the main source of public funding, the countryside stewardship scheme (CSS), as “not fit for purpose”, “overly complex” and a barrier to new woodland creation.

Despite several different funding streams for new forests, a Friends of the Earth analysis last year concluded funding for trees was “opaque, complicated and confusing”, and said the future of these grants looked uncertain.

Nevertheless, many in the sector think the time is now ripe for new policies as the UK leaves the EU and with it the common agricultural policy (CAP), which has been blamed for propping up otherwise unviable farming practices in the UK, such as upland grazing.

Instead of “basic payments” for each hectare of land under the CAP, English farmers will instead have access to funding through a new environmental land management (ELM) system, which pays them for “public goods” including afforestation. This new system, which is still under development, will be rolled out gradually over the next seven years.

The CCC has called for a range of measures to make tree planting a more attractive prospect, including a more streamlined application process for landowners. Its land-use report estimates a cost of £500m per year to reach the 30,000 hectare target, plus £200m per year to support agroforestry.

The committee advocates the use of both public and private funds to pay for this and says the “main instrument” should be market mechanisms, either a trading scheme or auctioned contracts similar to those for renewable energy. This, it says, could be funded by high-polluting sectors, such as airlines and fossil-fuel suppliers.

Forestry carbon credits are not included in the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS), although the UK does have the Woodland Carbon Code, which enables companies to offset their emissions and currently includes around 16,000 hectares of forest.

The Woodland Carbon Fund and Woodland Carbon Guarantee are other schemes that have already been set up to incentivise woodlands for carbon storage.

The CCC also warns that it is “important to ensure that carbon credits from land-based solutions are not allowed to reduce effort elsewhere in the economy”. Policy Exchange has stated that the current Woodland Carbon Code pricing is not high enough to ensure additionality, meaning projects it enabled could have happened even without it.

Ahead of the recent budget announcement, there was an expectation the chancellor Rishi Sunak would elaborate on the new £640m “nature for climate” fund, described in the Conservative manifesto.

The fund was mentioned as a means of driving 30,000 hectares of new woodlands over the next five years in England, but was criticised by scientists as being insufficient.

It also added to claims by campaigners that, despite the government’s poor recent performance on tree planting, it was still not providing sufficient financial support.

Additional, smaller funds were also mentioned, although these were dwarfed by the commitment to new infrastructure, such as road building.

How do international tree-planting efforts compare to the UK?

The UK is not alone in its goal to meet its climate targets with the help of afforestation. Carbon Brief has previously produced an interactive map showing where tree planting took place in the world from 1990-2015.

Tree planting and forest management are included in many nations’ Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement, with the land sector and forests in particular expected to contribute roughly a quarter of their pledged mitigation efforts up to 2030.

Major emitters including China, India, Brazil and Russia have all made it clear that forestry will be an important component in their climate-change plans.

Unsurprisingly, these large nations have dominated global tree-planting efforts, according to United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) data.

Other nations, including Ethiopia and Turkey, have also made international headlines following major afforestation pushes, prompting questions of how many trees it is possible to plant.

Top tree planting countries by 2015, showing the UK in comparison. Source: Global Forests Assessment, United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO). Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

Various international challenges have been set out to promote afforestation around the world. The Bonn challenge aims to restore 350m hectares of deforested land by 2030 and more recently the Trillion Tree campaign has gained traction.

However, there are significant concerns about the quality of the forests being planted around the world and how this will affect their carbon sequestration.

Globally, one Nature paper found that nearly half of the official tree-planting pledges in place would consist of monoculture plantations. But research has found again and again that mixed forests are better at storing carbon.

The paper, led by Prof Simon Lewis and co-authored by Dr Charlotte Wheeler, concluded that while natural forests could store 42bn tonnes of carbon by 2100 if the Bonn challenge was met, if 100% monocultures were planted just one billion tonnes of carbon would be sequestered.

This work makes it clear that while there is significant potential to combat climate change with trees, they are not the simple answer they first appear to be.

Even if the most ambitious Bonn challenge goal is met, it would still only account for around four years of current CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and industry (based on the latest estimates from the Global Carbon Project).

This means that most of the effort to reach net-zero emissions must come from reducing fossil fuel use, rather than simply relying on trees to offset emissions. Prof Nathalie Seddon summarises this issue:

“I just think the most dangerous thing about this whole focus on tree planting [is that] it is being used by some to distract and delay from the primary objective to keep fossil fuels in the ground…Because, actually, the numbers don’t really work.”

Teaser photo by Rural Explorer on Unsplash