Having studied, written on and engaged in public discussion about transnational corporations (TNCs), I have reached the conclusion that we are not collectively equipped to think about the kind of power that they represent, the silent way they exercise their specific form of sovereignty and the numerous mechanisms that allow them to circumvent the law wherever they operate.

To illustrate this, I will focus on just one corporation –Total – as a textbook case, and show what it is capable of globally, rather than piecing together several examples that could be accused of being selectively chosen just to satisfy our research needs.

Total is a corporate group headquartered in France, with operations in 130 countries, 100,000 employees and ‘collaborators’, and a daily production of the equivalent of 2.8 million barrels of oil. In 2018, Total reported net profits of $13.6 billion.

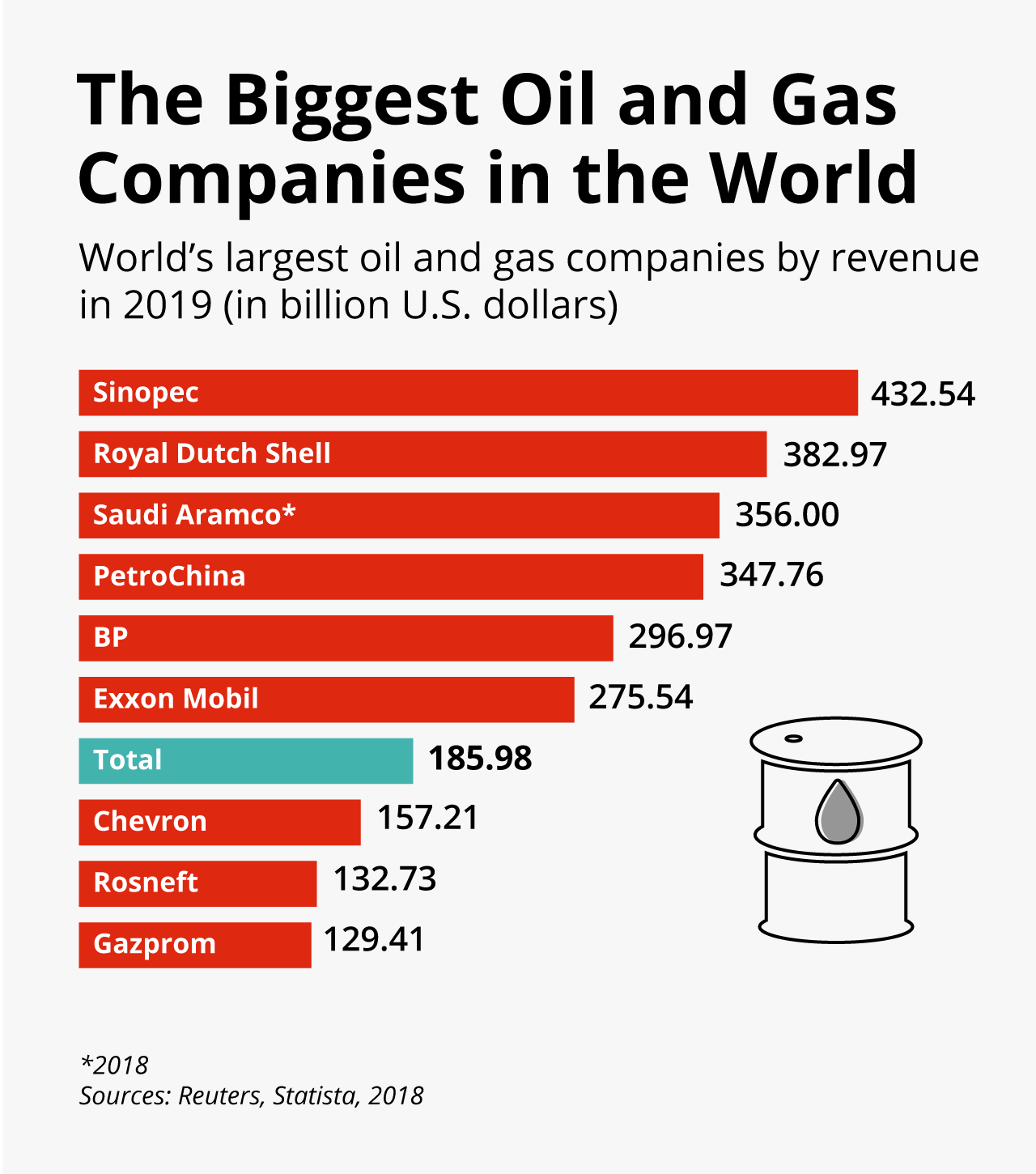

This energy giant, the world’s fifth-largest oil company and which has been around for almost a century, merits attention in view of the fact that it has been the subject of very little analysis, despite its shocking track record in human rights, the environment, public health and business ethics.

For instance, communities in Myanmar say they were forced to work on the construction of a gas pipeline. Dictatorships in Gabon and Congo-Brazzaville have received the corporation’s support for decades. It has openly used Bermuda as a tax haven to avoid paying taxes in France. And that is not to mention its polluting oil-exploration activities in northern Canada or the markets that it obtained following bombardments in Libya, to name just a few examples.

We begin by defining TNCs, disproving the image of Total as ‘a French oil company’, as is commonly believed. Each of these terms – ‘a’, ‘French’, ‘oil’ and ‘company’ – is misleading.

‘A’

First, by definition, transnational groups are not ‘a’ or ‘one’ company and do not formally constitute one legal entity, but hundreds of them – including its various subsidiaries, trusts, holdings, foundations, specialised firms and private banks.

These structures are legally autonomous, bound only by the laws of the jurisdiction in which they were created, but are in fact part of the networks that form transnational groups. They bill and even provide loans to each other.

Total has nothing in common with a local corner shop: it comprises 1,046 consolidated companies controlled by its board of directors on behalf of a common shareholder base.

If we were to imagine Total as an octopus the size of the Earth, the numerous states where its tentacles lie legislate only on what the tentacles within their territory do there; they are treated in isolation, as if they were not legally governed by the same brain or anything other than themselves. Total’s subsidiaries in Algeria, Bermuda, Bolivia, Myanmar, Qatar, the UK and the US have no official ties to the parent company based in La Défense in Paris, even though it coordinates their operations.

Only one law on the ‘duty of care’ passed in 2013 by the French National Assembly enforces the links of solidarity between them in cases where fundamental rights have been violated. In the rest of the world, through its subsidiaries, Total uses its full weight to influence each individual state where it establishes them, whereas none of these states is able to legislate at the global level, which is where the group is expanding its empire.

Each subsidiary is anchored in its respective territory as a local actor, while bowing to financial interests. In the global economy, Total finds all the flexibility it needs to escape the combined power of all legislation and all jurisdictions. It is at this level that, with full control over access to wealth, the subsidiary joins forces with other TNCs and can effectively dominate states.

‘French’

As for the word ‘French’, only 28% of Total is now French-owned. France no longer has any direct ownership, and institutional investors own 72% of the corporation worldwide.

In a series of waves of privatisation adopted by the Chirac, Balladur and Jospin administrations between 1986 and 1998, France got rid of its shares in Compagnie française des pétroles (CFP, owner of the ‘Total’ trademark) and in Société nationale Elf Aquitaine (trustee of the ‘Elf’ brand).

After intense negotiations, these companies merged with PetroFina at the turn of the millennium to form Total as we know it today. Chinese political authorities and the government of Qatar have since become shareholders, as have families who act as governors in their countries, such as the Frère family in Belgium or the Desmarais in Canada, for example. The latter held a seat on Total’s board of directors from 2001 to 2017. Today, US-based BlackRock is the majority shareholder of Total.

Total’s main shareholders are from the US, the UK and elsewhere. To date, the corporation has issued 2.6 billion shares that are not held by reference shareholders. In 2017, it dished out €6.1 billion in dividends to satisfy the beast and adopted the goal of increasing the rate from 5% to 6% per year, up from the previous 3%. It earned €11.4 billion in profits in 2018.

Since Total has no shareholder ties with France, its ‘French’ side amounts basically to its communications strategy. Back in 2015, the Énergies & environnement website announced that ‘[i]n 2012, 65% of its capital invested in refining and petrochemicals was concentrated in Europe, but the French oil company wants to reverse the trend by increasing the share of this capital in Asia and the Middle East to 70% by 2017’.

The corporation has invested enormously in megastructures, such as the one in Jubail in Saudi Arabia: investments of close to $10 billion guarantee Total 400,000 barrels of oil per day. Social and tax obligations are less strict in Saudi Arabia than in France. The corporation reduced the number of refineries in the city’s territory from eight to five – six including petrochemical sites. These are now generally either making a loss or their installations have been turned into niche entities.

‘Oil’

Screenshot of website: promoting its all-round energy solutions.

Total, the ‘oil company’, is reducing its focus on oil and petrochemicals and turning to diversification as a means to establish a place for itself in the sectors that will be favoured once it and its peers have depleted the last available oil deposits. Total clearly plans to exploit its deposits to the very last drop.

In 2017, it acquired assets in prospecting and exploitation and shares in two plants from the Brazilian Petrobras corporation for a total of $2.2 billion. In addition to those it already exploits in Gonfreville-l’Orcher (France), Anvers (Belgium), Jubail (Saudi Arabia), Port Arthur (USA) and Ras Laffan (Qatar), Total acquired an integrated refining and petrochemical platform in South Korea in 2017. At the time, it owned stakes in another 19 refineries worldwide, and continues to exploit the highly polluting tar sands in Canada.

By the 2040s, 35% of Total’s energy is expected to be produced from oil, 50% from gas and 15% from low-carbon energy sources such as biomass, solar power and storage. If global warming does not get the better of humanity after we have burned all the available fuel, Total anticipates having already redirected its distinguished customers towards its new energy markets.

Just as the chemical corporations BASF, Bayer, and Monsanto are quickly establishing themselves as the leading firms in the organic farming sector, Total is regaining control of the markets that compete with oil and working to turn its depletion into the market of the future.

The ‘Gas, Renewables & Power’ subsidiary is now Total’s fourth main business segment. Before its creation, management had plans for Exploration & Production (EP), Refining & Chemicals (RC) and Marketing & Services (MS). ‘The Gas, Renewables & Power segment spearheads Total’s ambitions in low-carbon businesses by expanding in downstream gas and renewable energies as well as in energy efficiency businesses’, it declared in its unique style.

Having tactically recognised its responsibility for global warming as an oil corporation, Total is now undergoing metamorphosis to make the gullible believe that ‘natural gas’, which it also exploits, is a solution. The group’s CEO is even advocating for the establishment of a reference carbon price that integrates the costs of CO2 emissions so that the price of coal serves as a foil for the gas sector.

However, opting to produce less oil in the long term and extract more shale gas instead is like choosing to pollute the atmosphere less (if we conveniently ignore the thorny issue of the methane that is released) to risk destroying groundwater sources instead.

Total uses the hazardous technique of hydraulic fracturing or ‘fracking’ in Australia, Denmark, and the UK and is aggressively arriving in or returning to the US, Argentina or Algeria to extract gas buried in rocks by causing underground tremors and whirlpools that potentially threaten the entire groundwater system – that is, when it is not launching deep-water gas prospecting and drilling projects such as those in Cyprus, Iran or Greece.

Total is also developing its shale-gas operations to target the markets for electricity and natural gas. For a while, it could rely on the support of Jean-Louis Borloo, the former French environment minister, who later became a ‘super-lobbyist for electricity in Africa’, as Le Monde newspaper put it. Borloo attempted to pave the way for relations in Africa among development fund directors, African leaders and French corporations such as Bolloré, Dassault, EDF, Total and Veolia that support the development of a vast continental electricity market.

By embarking on similar deep-water oil and gas projects, Total continues to push extraction from the ocean floor to new limits all around the world.

This does not, however, stop Total from advocating a clean economy, as it also produces solar panels. It became the world leader of solar energy after it acquired the US-based SunPower corporation in 2011 and then Saft in 2016 and it dominates the energy-storage sector.

This would make it a green company if we were to ignore – as it tries to do – the heavy metals that this industry requires. Total also carries out research in the energy-harvesting sector with the support of the Norwegian government. This new practice relies on the use of solvents that are capable of absorbing CO2 under certain conditions and its underground storage. Total’s efforts in this area are entirely self-serving, positioning itself ‘pre-competitively’ to respond to a technological demand that is anticipated from China.

Total is also drawn to agrofuels despite the threat they represent to food sovereignty, particularly in the Global South. It imports massive amounts of palm oil from South-East Asia to its French facility in La Mède – it needs 450,000 tonnes to produce approximately 500,000 tonnes of agrofuels per year – even though this operation is costly in terms of production, transport and processing, and thus, energy. Very little recycled oil will be included in their composition.

Palm oil plantations in East Kalimantan, Indonesia. Photo credit: European Space Agency/Flickr/CC BY-SA 2.0

As the CGT (French General Confederation of Labour) delegate Fabien Cros wrote on Total’s website, ‘All of this has a much bigger carbon footprint than if diesel were used directly! In sum, to produce this so-called green energy, we will pollute the rest of the world’. The satellite states in the Françafrique framework, such as Gabon, are following suit and plan to gradually convert to the agrofuels economy, rather than adopting agricultural policies to promote their own food sovereignty.

As the growth-based economic order must in no circumstances be stopped, Total is seeking to diversify it. There are several examples of this in 2019 alone. In addition to developing pipelines, lubricants, plastics and other petrochemical products, the corporation is involved in the battery and wood-pellets sector, and has also penetrated the hydrogen sector.

Despite the high cost of the chemical reaction needed to produce this energy, there is already lobbying for its promotion. Thus, to the gasoline sold through Total’s vast global network of retail service stations, we can now add natural gas and roadside charging stations for electric vehicles.

Total is busy not only producing these energy sources, but also trading them. It invests in structures designed to develop complex ways of selling these goods and has made some advances in the US and Japan.

In 2017, its subsidiary Total Marine Fuels Global Solutions positioned itself to sell massive amounts of marine fuel produced from liquified natural gas in Singapore. In 2016, it acquired the Belgium firm Lampiris, which buys 78% of the electricity that it itself sells. It returned to France in 2018 with Direct Energy.

It also plans to invest directly in its competitors’ funds such as Shell’s subsidiary in Nigeria or in Saudi Aramco in Saudi Arabia. Furthermore, it has invested in the Internet of Things and cutting-edge computer research. The corporation cannot claim that its operations are zero risk when it is developing a drone that is meant to ‘assess the extent of accidental pollution’.

‘Company’

Given the scale and level of diversity of Total (and its peers), it is no longer a ‘company’ in the sense of a meeting of duly identified business associates, nor an ‘enterprise’ understood as a structure engaged in a particular sector. Rather, it has become a power, a sovereign authority that sets itself apart from states and dominates and manipulates them to achieve its own self-serving goals.

Being a power rather than a simple company requires knowing how to take advantage of all situations – when, that is, the situation is not under its control in the first place. This diversity of activities and the fact that the company controls a multitude of aspects in the energy sector – prospecting, exploitation, transport, refining, processing, storage, distribution, trade, and so on – enables it to profit from each and every situation. Even though the price of oil dropped by 17% in 2016, the corporation still earned profits of at least $8.29 billion.

Johann Corric of Le Revenu observed that ‘The group’s accounts continue to be kept afloat by its downstream activities (refining, petrochemicals) and by a cost reduction plan implemented ahead of schedule. It exceeded its target of 2.4 billion dollars in savings for 2016 by 400 million dollars’.

Total has made reducing production costs a priority, which results in miserable wages, demanding working conditions, different treatment for local craftspeople and expatriates – these methods obviously please only the firm’s most powerful stakeholders: the Fitch credit-rating agency explicitly compensated Total for its strict management policies by stabilising the group’s rating at ‘AA–’.

Those nostalgic for state sovereignty are reluctant to consider the disturbing scope of these new power relations. Theoretically, as the guardian of the legitimate use of violence and the exclusive power to legislate, only the state should be in a position to assert its prerogatives over any private companies and foreign entities operating in its territory.

However, a new form of sovereignty is developing. Representatives of Total, its marketing industry and its tentacular PR services now have their say on and meddle in everything.

Total’s CEO Patrick Pouyanné, like his predecessor Christophe de Margerie, is involved in everything: the issue of the Syrian refugees, the trade embargo imposed on Russia, academic research, the revival of local industries, financial or technical support for small businesses, the fight against diabetes, museum exhibitions, the restoration of historical monuments and rejecting all social movements.

Recognised by states as a sovereign power itself, Total signed a declaration of support for the Paris Agreement at COP21 in which it pledges to work to keep global warming at the 2°C mark – even though in private, Pouyanné spoke about a significant increase of 3°C to 3.5°C.

Ideology of power

Our interest in using Total as a case study also stems from the fact that its representatives have become particularly vocal. Successive CEOs and various representatives do not hesitate to comment on their activities and even on current political affairs, giving us an insight into their fundamental ideology. In doing so, they inform the public of the ideological means they use to justify, in their own eyes, their authority. They present themselves in the long term as resolutely sovereign.

We analysed three types of sources:

- Total’s documents and public statements, as well as the publications of its historians and other intellectuals, which allow us to confirm by its own admission a whole series of facts.

- Specific legal documents that, depending on their status, provide evidence on specific matters.

- Critical and incriminating documents making claims to which the corporation’s directors have often responded.

We identified three constants in the corporation’s official discourse.

First constant: the presumption of legality

Whatever the form, Total’s representatives always insist on the legal nature of its operations. Whether dealing with its historical collaboration with the Apartheid regime in South Africa, the consultations that leave Latin American indigenous peoples frustrated, the influence peddling observed in Iraq or Iran in the late 1990s, the devastation of the Niger Delta region or the access to Algerian wealth enabled by odious debts, its rhetoric can be summed up as: we respect the law, we operate within the law, what we do is legal and as long as it is not prohibited (or sanctioned), it is permitted. These are the key phrases the group’s representatives use.

We took these claims seriously, so our work was not so much a critique of Total’s actions as an analysis of a system that allows so many actions to seem legal. We then asked ourselves about the very meaning of the phrase ‘it is legal’ in the various contexts in which it is used. We also examined how the corporation itself sometimes helps in drafting the legal frameworks that allow such actions to be considered legal.

Second constant: let bygones be bygones

When a journalist asked former CEO Christophe de Margerie about the suspicious commissions Total paid the Iranian regime in return for the concessions that it was awarded in the 1990s, he responded, ‘It’s good that you are starting to ask questions about dates because we can also talk about the Saint-Barthélemy massacre’ – which took place in 1572.

The firm’s representatives suggest that the historical slate should be wiped clean, perhaps in part to clear their conscience. For them, Total’s collaboration with the Apartheid regime is no longer up for discussion, even if its own documents boast that it has been in South Africa since 1954.

The TNC’s discourse minimises the past to favour only the present or a projected future. However, a firm’s capital, especially when it is colossal, is also its memoire, recording its actions in specific historical contexts. Capital is clearly crucial for any corporation, enabling it to take out loans, build partnerships, raise its share value on the stock market and invest in new projects in order to constantly expand it.

Minimising the past prevents the public from understanding how capital is accumulated – the very capital that now gives the group the means to launch multiple initiatives, reminding us of the saying, ‘the past guarantees the future’.

Third constant: don’t do politics

In issues involving Total in France and abroad, its representatives insist on saying that they do not do politics, then to add, only geopolitics. Together with other private-sector firms of the same magnitude, the corporation manages to shape much of the global industrial and financial order through a series of imperatives making it difficult for states to clearly exercise their sovereignty.

Whether in the chapter on procurement, pricing, diplomacy, lawsuits filed with ad hoc tribunals to ‘settle trade disputes with states’, lobbying and the establishment of power relations in regard to investment plans, everything is done to stifle debate on how liberal globalisation operates.

This is what led the current CEO, Patrick Pouyanné, to say that the left–right divide is obsolete and elections now merely endorse the neoliberal order that his group and several others helped to establish.

Moreover, since Total is active in all phases of the chain of exploration, exploitation, processing and distribution of energy assets, it can often avoid influencing the broader economic context, contenting itself with taking advantage of the stage of the chain favoured by the state of affairs at the time.

Conclusion

All these considerations led Total’s CEO to present himself as a sovereign ruler. After Patrick Pouyanné’s tête-à-tête with Vladimir Putin, which received all the pomp usually reserved for heads of state, he was quoted as saying, ‘Even if Total is a private company, it is the biggest French company and, in a way, it represents the country itself’.

Over and above this outrageous declaration, provoking not even a reaction on the part of the French president, the authority that corporate directors claim for themselves is supranational and specifically business-related. It is this power that now calls for further analyses and greater public awareness.

We need to treat Total not just as a large energy corporation, but rather as a private, multi- and transnational, private, sovereign power that serves the interests of a highly diversified shareholder base and intervenes in innumerable political, cultural, social, financial, industrial and academic issues.

This article is an abridged version of Alain Deneault’s book (In French), De quoi Total est-elle la somme ? Multinationales et perversion du droit, éditions rue de l’Échiquier et Écosociété (2017). Full references can be found in the book.