A Case for Recovering Forgotten Ethical Traditions in the Business World

————–

Albert Einstein famously remarked that we cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them. Put differently, an edifice will never be round if one lays a squared foundation, nor will a cello player perform decently by reading from a music sheet written for sax or for piano.

Faced with the scale of today’s societal and ecological challenges, Einstein’s dictum is timely for the business world. After more than two centuries of applauding industrialization and the growthism that has gone with it, it’s no news that we’ve currently surpassed human and planetary boundaries. And these, in turn, are calling into question the well-established mind-maps that have enabled us to get where we are at today.

Allegedly designed to overcome old harms, one of such mind-maps is found in the now-famous Creating Shared Value (CSV) paradigm and its different variants. Business prosperity, it affirms, should be shared, instead of coming at the expense of the broader communities where companies operate.

All good. In theory.

But despite its popularity ever since Harvard’s Michael Porter popularized it in 2011, perhaps we need a far more substantial approach to get us away from what Porter himself called the “vicious circle” implicit in today’s “old, narrow view of capitalism”. And this because the CSV-approach is close to a rebranded version of the “narrow capitalism” it aims to outflank.

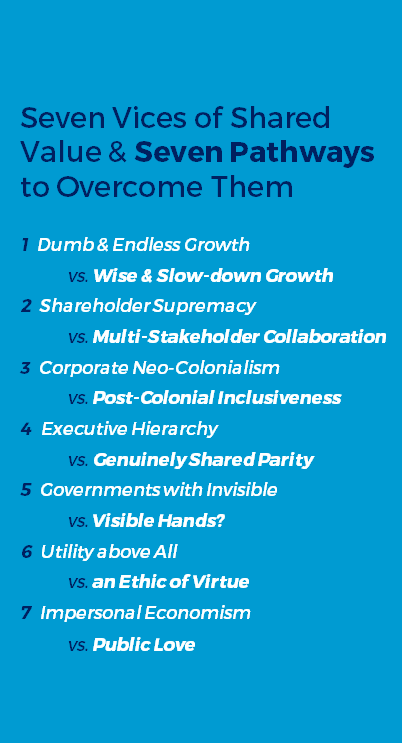

In contrast, drawing on this longer white paper, below is a sketch of

- one of the several hidden foundations of traditional business models that CSV paradigms fail to address;

- a pathway to move beyond shared value towards the recovery of virtue and of ancient spiritual horizons in the business world.

Dumb Growth or Smart Growth?

Following the CSV-paradigm, often proposals related to sustainability are coupled with phrases such as ‘enhanced brand value’, ‘creation of social capital’, ‘improving efficiencies’, and so on. Adjustments must be made, it is argued, so that the institution of business — as such — may continue to have its right to exist.

Even if slogans like these do have a valid place, however, often they are embraced under the ‘you-can-have-it-all’ sort of mentality that has characterized traditional business culture since the get-go. And they tend to ignore the pink elephant on the planet, bypassing how growth-based industrialism is in fact at odds with the limits of our overpopulated biosphere.

Not to say, of course, that all growth is unwelcomed: we do need the growth of regenerative agroecology, of 100% bio-based compostable packaging, of collective solutions to relocalization and urban mobility — to name just a few.

A collective solution to urban mobility, by Pixabay

Still, not all growth is good. For instance, even if Walmart has fortunately improved its distribution routes and has designed leaner, eco-friendly packaging, such cost savings can (and have) then leveraged the ongoing opening of new megastores. One step forward, but only to take two or three steps backward.

In Capitalism, As If the World Matters UK’s former Green Party member Jonathon Porritt once characterized this kind of mind-maps as perpetuating “dumb” economic growth. And that partially because the so-called ‘shared value’ may seem to increase, but so does net consumption. Betrayed by the very language we use, the pressure for expansion thus remains untouched. (And that’s just one of the several limitations of shared value.)

Leaving Behind 17th & 18th-Century Business Thinking

In The Moral Dilemma of Growth, former director of the New Economy Coalition Bob Massie examined what he called the “restless yearning for growth” that has characterized the United States since the 1600s. Having been economically and religiously repressed in Europe, industrious Puritan refugees and other European immigrants met (an already-inhabited) continent with an unexpected combination of opportunity and what seemed to be an unlimited amount of resources.

Back then, faith in business made perfect sense: population was small, material needs were big, and the land and its resources seemed unlimited.The combination thus fostered very much a religious enthusiasm for innovation, expression, and expansion. Liberty and the potential of growth appeared to be boundless, becoming imperatives quickly ingrained in American politics, economics, institutions, and culture.

Pilgrims in New England, by George Henry Boughton

But the world has changed more than a little since the 17th and 18th centuries. As Massie suggests, what we now need is more time, more peace, more calmness. And that, in turn, calls for business models of permanence that grow for a time, but only to stabilize and be put at the long-term service of fairness, wisdom, and life for all.

Shared well-being — instead of shared value — should be the aim of our companies and public policies. On balance, it was business that was created for humankind, not humankind for business.

How can today’s organizations begin to get there — all the way from enlightened B Corps to activist companies to social enterprises?

A Pathway from Value to Virtue

Many fruitful proposals have emerged in the last decades with alternative economic and business models responding to the challenge of expansionism — notably Tim Jackson’s Prosperity Without Growth or Herman Daly’s Beyond Growth. But space forbids us to reinvent their wheels.

However briefly, here it’s simply worth touching on two dimensions that can more fully nurture our journey towards more sustainable frontiers: the recovery of virtue and the need for transcendence.

To illustrate the former, recall the caricature of two elderly ladies trying to cross a busy street. One of them was aided by a teenager with a red cap; the other by a teenager with a blue cap. Both youngsters could be said to have accomplished the same action, assisting the elderly to get safely from one side to the other.

Still, the red-capped teen helped one of the ladies primarily to take a selfie and then get likes on her Instagram feed — she wanted to display her good deeds. Conversely, blue-capped teen assisted the other lady out of a sense of benevolence and duty — she did it ‘just because’.

Still, the red-capped teen helped one of the ladies primarily to take a selfie and then get likes on her Instagram feed — she wanted to display her good deeds. Conversely, blue-capped teen assisted the other lady out of a sense of benevolence and duty — she did it ‘just because’.

Not that the selfie wholly demerits the cause, but it carries an implicit risk.

Notre Dame’s moral philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre has shed light on the sort of motivations behind actions like these, contrasting them as “goods of effectiveness” and “goods of excellence”. In short, red-cap acted out of a want for recognition (effectiveness); blue-cap acted out of benevolence and virtue (excellence). The former’s desire for fame operates on a surface-level (it’s an “external good”); the latter’s display of virtue runs deep (being an “internal good”).

Hence the great unspoken danger of the CSV paradigms: one opts for ‘the right thing’ — not really because of its internal worth — but because of its external value: one does ‘good’ because and inasmuch as one can make a profit.

Virtuous Leadership

This illustrates the sort of dilemma we face in the business world. And it places a call to go stop weighing every action in the calculating scale of ‘utilitarianism’ towards taking heart to act out of excellence and virtue.

For example, when someone like Patagonia’s founder decided to go 100% organic in their supply of cotton fabric, he was not prompted by monetary considerations.

True, organic garments are more expensive and affordable only to certain populations. But listening to any of Chouinard’s interviews and conferences quickly reveal that his motivations for being responsible stem from a duty to do the right thing as best one can — in this case, by sacrificing the urge for higher-profit-margins-at-whatever-expense at the altar of the collective good.

Patagonia’s organic cotton fields, by Tim Davis

“Leading an examined business life is a true pain in the [a%*],” Chouinard remarked once. “It adds an element of complexity to business that most businessmen are not willing to hear.”

Patagonia’s governance structure allowed it to achieve this complex leap by following four major steps:

- making “an absolute decision” to take an “audacious” stand to switch to 100% organic cotton;

- working closely and strengthen the relationship with all its suppliers — from cotton farmers to spinners, knitters, weavers and dyers — to achieve the deep changes in farming and production methods necessary to make the shift;

- influence a wider change in society toward more sustainable agriculture, through catalogues and in-store education;

- influence other clothing companies to use organic cotton (ongoing, and mostly failing due to low-adoption rates).

Something similar could be said of a restaurant chain that closes its doors on Sundays in all of its 2,300 locations. Such is the case of Chick-fil-A, a privately-owned company that respects the ancient Jewish tradition of a common day of rest — a practice the company has observed since its foundation in 1947.

Leaving aside for a moment Chick-fil-A’s controversial position towards the LGBT community, as well as its shortcomings regarding the many ethical considerations around eating animals, it could be argued that owner and CEO Dan Cathy has opted for closing all stores on Sundays merely for PR purposes.

A restaurant chain that closes on Sundays, ever since 1946

But even if there was some sort of marketing motivation behind it, the practice is commendable for being grounded in the owner’s willingness to express the counter-cultural virtues of his faith by living them out in the business world — in this case, by working out the (often unprofitable) duty to care for one’s neighbor and the biblical mandate to allow the land to rest.

Not to say that Patagonia or Chick-fil-A ‘have arrived’, because every company is compromised in one way or another (the Cathys have often been discriminatory following their same-sex marriage stance). Still, what is commendable is how instead of seeking recognition or effectiveness, both Chouinard and Cathy are business executives at least oriented towards excellence and virtue. And, however imperfectly, they thus begin to display the sort of values-first/beyond-profit, transcendental leadership that we need as we face the challenges of the 21st century.

(Quite surely, something similar could be said of Anita Roddick of the Body Shop, or of the founders of Cadbury Chocolate, both of which were known for recovering and pursuing the forgotten horizons of ancient spiritual traditions.)

Recovering Old Horizons of Transcendence

In response to the question of the managerial styles he found most promising, Ashoka’s founder Bill Drayton has spoken about the need to radically reframe business leadership models and priorities.

Convinced as he is that the world needs social entrepreneurs who are committed to a noble mission, Drayton pointed back to the ‘everyone-a-change-maker’ example of the medieval order of the Jesuits.

“Are you really maximizing works in faith? And do you do it with love?” he responded by highlighting the 16th-century spiritual exercises of Ignatius of Loyola. “This is old language, but that’s what you need in today’s organization.”

Ashoka’s founder Bill Drayton, photo by B the Team

Faith and love are certainly not two words that figure in most business textbooks. But if we are going to somehow honor Einstein’s dictum highlighted above, it follows that we must look beyond the seductive smokescreens of utility and value. And such challenge, I’d like to propose, calls for recovering the transcendental grand-view cracked open by the millenary spiritual traditions that we have either distorted or dismissed in our secular Western worlds.

As laid out in A Climate of Desire, this places a call for stretching our personal and collective aspirations into the infinite horizons of eternity. It also calls us to recognize that the furnaces of hope will light up once we allow the stars to shine brighter than our neon lights.

Will business leaders look beyond the confinement of their walls? Will virtue and excellence be put at the service of life, reorienting our companies’ raison d’être and stretching their goals to prioritize a truly multigenerational, long-term view?

* * *

“A picture held us captive”, said once Ludwig Wittgenstein. “And we could not get outside it, for it lay in our language and language seemed to repeat it to us inexorably.”

This and all the above to remark that there is an entirely new world waiting for us beyond the limiting (and often illusory) picture of shared value. Far more promising, instead, is the radical healing and bold transformation required of today’s business enterprise — a journey in which the very language we use (let alone the virtuous practices that should go with it) may very well be the starting points towards more excellent destinations.