At this point in human history, the limits of capitalism and the limits of our species’ life on Earth have converged. We have never been here before, and we cannot go back.

The political activism of my youth was largely in solidarity with anti-colonial movements in Africa and Palestine, anti-US imperialist movements and dictatorships in Latin America, and solidarity-building between the labour and other social movements around a broad program of democratic, anti-capitalist reforms. In those struggles, there was always an assumption that social transformation could draw upon the resources of a reasonably intact natural world. No more. Capitalism, patriarchy, and racism now threaten to destroy this world, along with its tenuous civilizational achievements. We are all of us, now, face to face with the kind of ‘deworlding’ that traumatized Indigenous peoples following the arrival of colonizers.

We, on the left, keep trying to find analogous moments in human history (the rise of fascism, world war two) when ‘normal’ life is upended and nothing can go on as before – including academic work, which must give way to activism on every front. Apart from the threat of nuclear war, humans have never faced a ‘limit’ like this, and even that threat was unlike climate destabilization because at least it could be controlled by disarming the technology. What we have set in motion now, in the capitalocene, is likely beyond technological solutions, notwithstanding Promethean male fantasies of Mars colonies and planetary geological engineering.1 What we have set in motion is now, at least in part, beyond human control. That is, no re-engineering of social relationships and modes of production will reverse the biological and physical processes that have been unleashed.

Breakdown of a Climatic System

In the span of a single lifetime, since WWII, industrialized societies have loaded enough greenhouse gases (GHG) into the atmosphere – mostly from the combustion of fossil fuels – to cause the breakdown of a climatic system that was relatively stable and friendly to biodiverse life for 800,000 years.2 More than half of all the GHGs emitted since 1750 have been emitted since 1989 – that is, when we knew what we were doing.3

To give you just a few examples of climate breakdown: Thawing soil in the Arctic is now releasing an estimated 600 million tons of C02 per year – an amount that exceeds the CO2 emissions of 189 countries. This is a biofeedback effect of warming at the north pole, which has now warmed by 4ﹾC (over the pre-industrial average).4 This is not a genie that we can put back in the bottle.

Our emission of greenhouse gases has caused ocean warming,5 acidification, and anoxification. One of the (frankly terrifying) consequences of ocean warming is reduced phytoplankton growth. Phytoplankton are the basis of the marine food chain, producers of half of the oxygen in the Earth’s atmosphere, and drivers of the “biological pump that fixes 100 million tons of atmospheric carbon dioxide a day into organic material, which then sinks to the ocean floor…”6 They are responsible for half of the photosynthesis that takes place on Earth’s surface, although they account for less than 1 per cent of photosynthetic biomass. Studies indicate that phytoplankton biomass has decreased by more than 40 per cent since 1950 and continues to decrease at an increasing rate.7 Scientists warned in 2010 that if – due to warming surface waters – the phytoplankton in the upper ocean stop pumping carbon down to the deep sea, atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide will eventually rise by another 200 ppm and global warming will accelerate.8 (We’re now at about 411 ppm, having passed 400ppm in 2013.)

Meanwhile, the die-off of phytoplankton, kelps, and corals has already affected marine species that depend on them for food or habitat. With the crash of wild fish stocks (due to multiple causes, in addition to global warming) humans are losing a source of protein that currently supplies one fifth of our protein consumption. One marine scientist says that, “in the best case,” it will take another 1,000 years “for the current damage to be reversed.”9

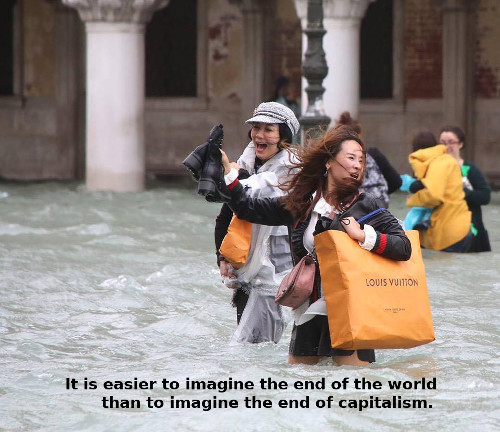

Eco-Marxists like John Bellamy Foster and Brett Clark have drawn attention to Marx’s investigation of the problem of the loss of soil fertility in 19th century Britain, following the commercialization of agriculture and changes in farming practices.10 I picture Marx in the library at the British Museum, devouring all kinds of contemporary science, and wishing he had time to follow all the threads. I suspect that Marx would have been very interested in the life cycles of phytoplankton, had their existence been known to him. Could he have imagined that capitalism could survive in the face of widespread knowledge that it is destroying the conditions for life on our planet? That we could we arrive at a place, where, for millions, it is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism?11

From the Catastrophic to the Unthinkable

Future scenarios range from the catastrophic to the unthinkable. We are now on track for warming of more than 4ﹾC by 2100,12 or 3.5ﹾC if all countries actually meet their Paris COP commitments, and 8ﹾC is no longer impossible (although we do still have a window of opportunity to hold the global average temperature increase to the lower end of the spectrum). In a 4ﹾC world, climate models predict that the planet will not have the carrying capacity to support the current human population.13 Professor Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, an eminent climate scientist and director of the Potsdam Institute, said earlier this year that “at 4ﹾC, Earth’s … carrying capacity estimates are below 1 billion people.”14 Professor Kevin Anderson of the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change has reached a similar conclusion, estimating that “only about 10% of the planet’s population would survive at 4ﹾC.”15

The UN predicts that there will be 200 million climate refugees by 2050.16 Depending on by how much global temperature rises, there could be “a billion or more vulnerable poor people” displaced from their homes by mid-century.”17 Today’s governments are unable to co-operate to deal with 6 million Syrian refugees. Instead, most are building higher walls, using coast guards to turn back ships, and building detention centres.

And, of course, one can go on… I haven’t touched on the effects of chemically-and-fossil-fuel-intensive agriculture, beef consumption, over-fishing, toxic chemicals, plastics, industrial pollution, and so on. I haven’t mentioned the great loss of other species – half of all non-human life on the planet in my lifetime in this sixth period of mass extinctions. Our destiny is entwined with that of the other species with whom we share the planet.

That the over-shoot of planetary ecosystem boundaries is a limit to capitalism – and to human population growth and consumption – like no limit we have faced before, is what the global movement of school-strikers is trying to tell us. It is what the Extinction Rebellion movement is telling us.

Political Economy

What does this mean for political economy? Well, if I can repeat an argument I made in the pages of Studies in Political Economy in 1994 (25 years ago!) we have to stop thinking, programmatically, in terms of economic growth.18 We must take up the calls for degrowth – in whatever discursive form best fits our political contexts – and for the rapid decarbonization of our systems of production, consumption, communication, and transportation. This is not the moment to rally behind incremental, contradictory, and often socially regressive, market-based approaches to environmental regulation; it is the moment to shift popular consensus in the direction of a much more radical agenda of reforms rooted in ecological and egalitarian principles. This agenda needs to be developed regionally, by civil society actors, taking into account local ecosystems and other factors, but in connection with other regions. We are at a crossroads where either global apartheid and authoritarian, nativist regimes will prevail, or a radical democratization from below motivated by humanist and universal values as well as love of biodiversity.

Actions like protests and civil disobedience need to be articulated to an agenda of reforms to realize political democratization and green transition. Where civil society is weak and disorganized – as in Alberta – we need to bring together our intellectual, institutional, and leadership resources to develop a program around which we can mobilize support. A major resource in this regard is the university, but disciplinary and incentive structures mean that there are trenches that must be won here, too, for the university’s resources to become available to community partners.19

Elections seem to be windows of opportunity and it is understandable that we turn our energies toward the debates and campaigns – and to preventing the worst outcomes. But given the existing institutional barriers to electing a green-left government, I think we should prioritize the work of coalition-building and democratic planning – bringing forward concrete alternatives that people can fight for. The slogan “What do we want? Climate action!” is a starting point, but it puts the ball in the court of governments (and economists) that are only going to offer market-based measures – at best – or delay meaningful action.

A few further points with regard to planning for green transition:

- Instead of thinking in terms of full employment, we need to be thinking about how to ensure income security that is delinked from wage-labour and – for farmers – from commodity prices.

- Instead of thinking about raising revenue only in terms of taxation, we need to be figuring out how to finance a rapid energy transition and other measures through public banks and public ownership of the new sectors.

- In the Canadian context, green transition must also take as a starting point the restoration of land to Indigenous peoples and recognition of their full sovereignty over those lands.

- A lot of thinking has been done about the general directions for green transition, and coalitions are starting to come together at provincial and municipal levels.

This organizing work is also a way of coping, psychologically, with the overwhelming grief that many of us feel about the world we are losing – a world our children will never know – and about the world they will be inhabiting in the decades ahead. At the very least, we must be able to say we tried.

Greta Thunberg uses the phrase: “We will not be bystanders.” I don’t know if this is her intention, but this phrase could be a reference to the choices available to people in the 1930s, as they observed the rise of fascism and the deportation of Jews, Communists, homosexuals, the disabled, the gypsies, and others to “concentration” camps.20 Thunberg’s call is a moral one, recognizing that the world’s poorest populations will be the most devastated by climate destabilization. Shall those of us who are privileged to live in the northern hemisphere and in the global middle class ‘stand by’ while millions die, or flee, from the disasters wrought by global warming?

Will we ‘stand by’ while short-term greed renders our planet uninhabitable for future generations? Or we will commit ourselves fully to making another future possible? To wresting power from the ecocidal one per cent and its governments? •

To mark its 40th anniversary, Studies in Political Economy, A Socialist Review sponsored a conference October 26 at Carleton University, Ottawa. The theme: “The Limits of Capitalism and the Challenge of Alternatives.” Among the speakers was Professor Laurie Adkin of the University of Alberta, who addressed the conference via Skype. Prof. Adkin has kindly agreed to the publication here of the notes she prepared for her panel presentation, in my opinion an outstanding contribution — Richard Fidler.

Endnotes

- On carbon capture, for example, see Mark Z. Jacobson, “The health and climate impacts of carbon capture and direct air capture,” Energy & Environmental Science (2019) [DOI: 10.1039/C9EE02709B].

- Rob Moore, “Carbon Dioxide in the Atmosphere Hits Record High Monthly Average,” Scripps Institution of Oceanography, May 2, 2018.

- Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Centre, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, “Global, Regional, and National Fossil-Fuel CO2 Emissions” (Oak Ridge, TN. 2-17).

- Joe McCarthy, “Soil in the Arctic is now releasing more carbon dioxide than 189 countries,” Global Citizen, October 23, 2019. The report is: Susan M. Natali, Jennifer D. Watts, Donatella Zona, “Large loss of CO2 in winter observed across the northern permafrost region,” Nature Climate Change, 21 October 2019.

- About 90 per cent of the heat trapped by greenhouse gases is absorbed by oceans.

- Quirin Schiermeier, “Ocean greenery under warming stress,” Nature 28 July 2010 [doi:10.1038/news.2010.379].

- Ibid.

- A paper in Nature, published in 2012, explained that the atmospheric level of carbon dioxide had already risen to more than 390 parts per million. This is 40 per cent higher than before the industrial revolution. See Paul Falkowski, “The power of plankton,” Nature vol. 483 (1 March 2012), S17-S19.

- Paul Falkowski, interviewed by Michael Eisenstein, in Nature 483, S21 (29 February 2012).

- John Bellamy Foster and Brett Clark, “Ecological Imperialism: The Curse of Capitalism,” in Socialist Register 2004, pp. 186-201.

- No, I don’t know who said it first! But see Fredric Jameson, “Future City,” in New Left Review, May/June 2003.

- IPCC, Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report, Summary for Policymakers (Geneva, 2014), p. 11.

- David Wallace-Wells, “The Uninhabitable Earth” (annotated), New York Magazine, July 10/14, 2017.

- Quoted in Robert Unziker, “Earth 4C Hotter,” Counter Punch August 23, 2019.

- Ibid. See also, the map of the world at 4ﹾC by Parag Khanna.

- Baher Kamal, “Climate migrants might reach one billion by 2050,” ReliefWeb, August 21, 2017.

- United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification, “Sustainability, Stability, Security.”

- Laurie Adkin, “Environmental politics, political economy, and social democracy in Canada,” review essay in Studies in Political Economy no. 45 (Fall 1994), 130-169.

- This internal war of position is made harder when the universities are under attack by neoliberal petro-politicians, as is the case in Alberta. But the priorities of university research and the shaping of their degree programs are influenced, more generally, by corporate-government-determined “innovation” agendas. (See Laurie Adkin, Knowledge for an Ecologically Sustainable Future? Innovation Policy and Alberta Universities (Edmonton, AB: Corporate Mapping Project and Parkland Institute, forthcoming in 2020). Moreover, most universities have now implemented budget models that allocate revenue by performance criteria that put faculties (and departments within faculties) in competition with one another for student enrolments and external research funding. This competition suffocates interdisciplinary research and teaching. On the other hand, within faculties there can be a stronger esprit de corps and a degree of politicization vis-à-vis the neoliberal state.

- It is not surprising that analogies are made so often between the effort needed to wrest power from the ecocidal one per cent and its governments, on the one hand, and the massive mobilization that was necessary to defeat fascist governments in WWII, on the other hand. There are significant differences, worthy of consideration because they are of strategic importance. For example, some governments mobilized their populations to fight Hitler and Mussolini; today, it looks like we are going to have to mobilize ourselves against our own governments.