The 1973 dystopian science fiction film “Soylent Green” is set in the year 2022, just one year after a nonfictional Finnish company hopes to begin selling an artificially produced yellow protein-laden flour created by bacteria that the company says will revolutionize food production.

The flour is derived from vats of yellow bacteria whose fermentation process create a yellow protein that when dried looks like flour. That yellow flour contains 50 percent protein, 20 to 25 percent carbohydrates and 5 to 10 percent fat. This basic foodstuff can then presumably be turned into products such as meat substitutes, bread products and filler in myriad foods needing a protein boost.

The entire process takes place indoors and the company claims that it dramatically reduces the amount of water, land and other resources needed to grow or raise the equivalent amount of protein using modern farming techniques.

The normally sober-minded environmental columnist, George Monbiot, tells us that this process may be 20,000 times more efficient than farming and could in the future produce protein that is one-tenth the cost of animal protein. So-called “farm-free” foods as a category could lead to the collapse of the global livestock industry by 2035 when industry boosters expect meat to be grown primarily in factories.

What makes Monbiot a fan? It is the possibility of returning vast tracts of land to the wild for regrowth that could potentially reverse climate change. These food production methods also address the growing need for food among a continuously increasing human population in a world now cursed with climate change—climate change so bad that it will turn our current breadbaskets into dustbowls.

Can we blame Monbiot for looking for solutions, any solutions that won’t involve the collapse of human society?

But can such methods actually do what they promise? And, if they can, do we want them?

The first problem I see is that food is as much a cultural artifact as a biological necessity. And, growing it is as much a cultural act as preparing it and eating it. The disappearance of farms in favor of industrial vats will certainly take some getting used to.

Second, farming has been a robust form of food production for at least 10,000 years. We have a lot of knowledge about how to do it, and we humans have been exceedingly successful at making it work for us. After all, there are almost 7.8 billion of us on Earth. What happens if this new, barely tried system doesn’t work in the long run and we find out only after much of our farming knowledge has disappeared. Keep in mind that most of the knowledge about farming isn’t in books. It’s in farmers’ minds. What happens when we have few or none of those minds left to reteach us how to grow food.

Third, the unintended consequences of switching much of our food supply over to factory production will undoubtedly be many and significant. The most obvious issue is what to do with all those currently engaged in farming who will be out of a job. And, there will likely be many other unintended consequences which we cannot foresee and which might unpleasantly surprise us. The shrinking diversity of food sources used to feed humans and livestock will become an even bigger problem should we become dependent on two or three strains of bacteria for our main sources of protein.

Finally, there is what I’ll call for lack of a better term the “yuck factor.” I am reminded of the old joke that one does not want to witness how laws or sausages are made.

In the film “Soylent Green,” climate change is well-advanced. Charlton Heston plays a police detective who is always dripping with sweat. The mainstay of the human diet is a protein-rich food called soylent which comes in red, yellow and green, green being the tastiest and most difficult to get. Real honest-to-God food, when it appears, is valued like gold and carefully hidden from others. For those who haven’t seen the film, just let me say that the “yuck factor” plays a central role in the plot.

I am also reminded of those rare scenes in the “Star Trek” television franchise when characters discuss “real” food versus what comes out of the ship’s food replicators. Their eyes widen (and though they should be salivating, that part is too unseemly to show on television). The character who purports to have eaten real food is gazed upon with wonder and envy.

Will we become like those characters in “Soylent Green” and “Star Trek” who go all misty-eyed at the thought of genuine food? I don’t think we will because I believe that somehow factory food production will prove much more problematic than the inventors have foreseen. I can only hope that we will find that out before we reach the point of no return. Otherwise, many humans will be condemned to malnutrition and starvation because our “solution” to a climate-induced food crisis didn’t work out.

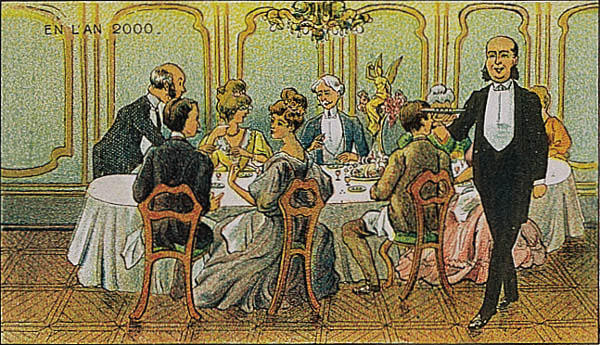

Image: A Chemical Dinner in the year 2000. French post card (1910). Via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:France_in_XXI_Century._Chemical_food.jpg