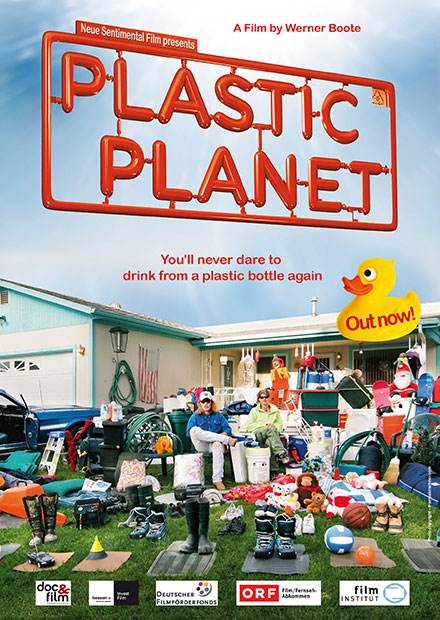

Plastic Planet

Plastic Planet

Written and directed by Werner Boote

Cinematographed by Thomas Kirschner

Edited by Ilana Goldschmidt, Jack Moik, Tom Pohanka and Cordula Werner

Produced by Thomas Bogner and Daniel Zuta

Executive produced by Tom Gläser and Ilann Girard

Music by The Orb

Additional music composed by Andreas Lucas

Special effects by Cine Cartoon Filmproduktion and SVC

A production of Brandstorm Entertainment, Cine Cartoon Filmproduktion, FunDeMental Studios, Neue Sentimental Film Entertainment GmbH and Zuta Filmproduktion

Release Date: Sep. 2009 (Austria)

Running time: 99 minutes

Of all the documentaries that have been made about the dangers of plastic, the one that has stuck with me the most is Plastic Planet. It’s my favorite for numerous reasons, the first of which is the breadth of its scope. Whereas some films focus on just one facet of the issue, such as plastic in the ocean, this one surveys the entire picture. Other qualities I admire about Plastic Planet are its uncompromising realism, its finely written narration, its very effective musical score, its droll eccentricity and the way it doubles as a deeply affecting memoir by someone with a long personal history with plastic.

Filmmaker Werner Boote is that someone, and his feelings about plastic are conflicted. On one hand, he grew up enamored of the stuff thanks to his late grandfather, who worked in the German synthetics industry and surrounded his grandson with all manner of miracle products made from plastic. (Boote recalls how his toy collection made him a hero among the neighborhood kids.) However, as an adult living in an age of greater scientific understanding, Boote knows that his grandfather’s work immersed him in chemicals that altered his biology and likely contributed to his early passing. Boote’s goal in making this documentary was to investigate the perils that attend our society’s plastic addiction, and what we can do about them. The film takes us along on Boote’s journey, which turns out to involve just as much inner contemplation as discovery about the ills of plastic usage.

While Boote repeatedly mentions the time his grandfather spent toiling in a plastics factory, a key takeaway of this film is that you need not have worked in plastics manufacturing to have suffered from exposure to plastic’s harmful chemicals. Moreover, you need not even have lived someplace where plastic is widely used: Research has shown that everyone, even those in traditional indigenous societies, has plastic in the blood. A few months ago it was even reported that Arctic snow and sea ice are now suffused with microplastics, the original plastic objects having been weathered down into tiny fragments that then became airborne and fell back to the ground along with snow. In short, Boote is entirely correct when he remarks at the film’s outset that there is no pure, untouched nature left on our planet.

Boote concedes that for all its adverse environmental and human health impacts, plastic does have advantages over its alternatives. Bottles made from polyethylene or polypropylene are lighter and more durable than glass bottles, making them less expensive—in both money and energy terms—to transport, as well as less fragile. Plastic in general is an incomparably versatile substance, capable of being fashioned into everything from drink bottles to packaging to outdoor furniture to clothing to high-pressure pipes. Boote admits to being seduced by plastic’s magical chameleon-like nature. At one point he’s making his way through a trade show, ready for a big confrontation with a prominent plastic industry leader, when he sees a sleek, shiny hot rod with an all-plastic body. He climbs in and works the controls with a boyish grin. “I’ve hardly entered the exhibition hall,” he says, “when I feel my grandfather next to me. He shows me all the wonderful cars, motorbikes and rockets. A real dilemma.”

The first couple of interviews in Plastic Planet are with plastic industry stakeholders. As one would expect, they display exactly the same sort of awe over their product as Boote does in that hot rod cockpit. Chemist Peter Lieberzeit describes the process of creating plastic as “Lego for grown-ups,” with hydrocarbon molecules standing in for the toy blocks. He asserts that plastic production is safe and that there’s a “practically negligible” risk of harm to one’s health from touching plastic—claims that Boote knows to be false (though we don’t see him challenge Lieberzeit). Boote also talks with John Taylor, president of industry group PlasticsEurope and chief executive of polyolefins manufacturer Borealis. While extolling the virtues of plastic, Taylor has a smile that would do the Cheshire Cat proud. Asked whether plastic isn’t more of a burden than a benefit to society, he first punts the question (“Do you feel that?” he asks Boote back) and then minimizes the issue, avoiding any mention of plastic’s problematic aspects beyond the obvious one of litter.

Regarding plastic’s dark side, our second group of experts shows as much openness as the first group did evasiveness. Among others, Boote interviews a human health scientist, a reproductive biologist, a pharmacologist/cell biologist, an environmental toxicologist, an environmental analyst, the senior vice president of the World Wildlife Fund and the boat captain/oceanographer famous for first bringing widespread attention to the Great Garbage Patch in the Pacific Ocean. The litany of bad news they have to deliver is so dire and seemingly interminable that it feels like we’re stuck in a never-ending nightmare. The filmmaker also has his blood drawn and analyzed to find out how much of the estrogenic, endocrine-disrupting chemical bisphenol A his body has absorbed. (The answer, according to biological scientist Frederick vom Saal, is that it’s enough for him to produce an abnormal baby.)

Bisphenol A and the group of chemicals known as phthalates are among the more harmful compounds found in plastic. Bisphenol A is in beverage bottles, food can linings, food storage containers, tableware made from polycarbonate and countless other products. When you put water into plastic containers made with bisphenol A, the chemical leaches into the water, especially upon heating. Endocrine biologist Scott Belcher explains that by mimicking estrogen, bisphenol A can interfere with brain development and functioning. Phthalates are just as ubiquitous as bisphenol A and are especially apparent in that film that coats the inside of a car windshield on a hot day, says vom Saal. The heat causes the car’s plastic interior parts to off-gas their phthalate content, which the car’s occupants then inhale. The phthalates go on to stimulate body weight gain, alter fetal development and reduce testosterone levels and sperm production in men, among other nasty things.

The filmmaker notes that in the time since plastic first became big in the 1960s, there’s been a 50 percent drop in human sperm production. We don’t yet fully understand the cause of this decline, and Boote is careful not to posit a causal link to plastic exposure (just as he never definitively says that his grandfather’s work in plastic production killed him). So concerned was Boote by this trend that he commissioned his own, first-of-its-kind study of sterile couples. The study sought to answer the question of whether sterile couples have more plastic in their blood than do non-sterile couples. Curiously, Boote neglects to tell us whether the study’s findings bore out its hypothesis. He implies that they did, however, by way of a scene in which he and a fellow researcher counsel a couple on their results and recommend ways to rid their home of polyvinyl chloride (PVC).

Boote has a bit of the performer in him, and when he lets this side loose it makes for some thoroughly entertaining—and at times captivatingly weird—theater. My favorite set-piece is one in which he stands in the middle of a crowded marketplace with a bullhorn, shouting “Plastic causes cancer,” “Plastic causes allergies,” “You will get big breasts” and “Plastic harms your descendants,” among other blunt facts. We later see him slapping stickers with similar messages onto plastic bottles in a supermarket. And while visiting the production line of a company that makes biodegradable plastic, he rubs a handful of the bioplastic pellets all over his face to show his delight at how natural they feel and smell. Boote’s antics provide just the comic relief this film needs.

A big part of what makes Boote’s portrait of plastic so engrossing is its experiential approach, which seeks not only to impart knowledge but also to engage our senses. Boote makes a point of smelling the various types of plastic he encounters, and he admits to becoming “stoned” off the scent of one of them. He goes to a refinery where crude oil is turned into PVC and dips his fingers into a beaker of crude, a move he’s told could damage his blood if the oil diffuses through his skin. Later, while visiting a landfill in the Indian city of Kolkata, he sifts through trash with a ragpicker and tastes a piece of salvaged plastic. He handles even more trash while volunteering for an annual cleanup effort off the Japanese island of Tsushima, where vast quantities of plastic wash ashore each year.

Plastic Planet’s soundtrack is another of its high points. Written and performed by the electronic music group The Orb, with additional music composed by Andreas Lucas, it has a psychedelic, atmospheric sound that knows exactly how to perturb us with its stretches of unsettling quietude and eschewal of melody and rhythm.

A pall of death and loss hangs over much of this film. We hear from the daughter of a man who blew the whistle on a PVC plant where 170 employees died of cancer and 377 became seriously ill. We meet Japanese sculptor Hiroshi Sagae, known for the amazingly realistic figurines he handcrafts out of plastic. Sagae confides that he fears for his health after a friend died from inhaling plastic vapors. (Sadly, Sagae himself passed away just a couple of months ago from cancer at 52.) And the film’s parting image is of Boote’s grandfather’s grave. Boote and his mother go there to lay down a fresh bouquet of flowers, and Boote tells his mother he’s proud of her for having gotten rid of the old plastic flowers.

Though Plastic Planet does touch on plastic alternatives, it has the candor to acknowledge that they aren’t a panacea. Boote points out that the plastic detritus already flooding the biosphere will take at least 500 years to break down, and thus even if henceforth we were to use only harmless plastic, we would still need to contend with vast quantities of traditional, toxic plastic in our environment for centuries to come. “Will there still be life on our planet then?” muses Boote darkly. This film’s core message seems to be that, in the interest of not worsening our predicament, we should all eliminate plastic from our lives as much as possible. However, we shouldn’t trick ourselves into believing that in doing so we’ll somehow be magically solving the mess we’ve already made of things.