If we want a new economy, we need a new economics. Kate Raworth, author of Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist, talks with Tellus Senior Fellow Allen White about what mainstream economics gets wrong and how “doughnut economics” can open up possibilities for nurturing both people and planet.

To start, what drew you to the field of economics?

Looking back to the 1980s, when I was a teenager, I can vividly remember watching the TV news cover the famine in Ethiopia, the hole opening in the ozone layer, and the deepening problem of the greenhouse effect. For me, these were defining events. By the time I was ready for university, I wanted to help change the world and study a subject that would equip me to do so. I majored in economics, philosophy, and politics at Oxford, but I gradually became disillusioned with economic theory and the lack of discussion of topics that I really wished to pursue, such as ecological integrity and social justice.

Following my undergraduate work, I obtained a Master’s Degree in development economics and then worked as a civil servant in Zanzibar at the Ministry of Trade Industries and Marketing. This was a formative experience, working closely with barefoot micro-entrepreneurs and witnessing economics in the context of human survival. I realized that I never studied power, gender, and the dangers of reliance on expert knowledge. I then co-authored UNDP’s Human Development Report for four years, and joined Oxfam as a researcher, covering the exploitation of women in global supply chains, the neglected value of women’s unpaid caring work, and the social injustice inherent in climate change.

These first twenty years of my career focused on trying to make visible things left invisible by mainstream economics, and I was determined not to spend the next twenty years doing more of the same, from the margins of the profession. When the 2008 financial crash triggered calls for new economics thinking, I already believed we needed new thinking to respond to both the ecological crisis and the crisis of inequality. So I left my job at Oxfam, immersed myself in all the economic perspectives I had never been taught, and asked myself what would happen if the insights of ecological, feminist, complexity, behavioral, and institutional economics were all to dance on the same page. The result was doughnut economics.

What is “doughnut economics” all about?

In my book, Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist, I try to reframe economics through the power of images. The diagrams that we draw profoundly shape our thinking. If we’re going to thrive in the twenty-first century, and if economists are going to be helpful in doing so, we need to rename and redraw the economy.

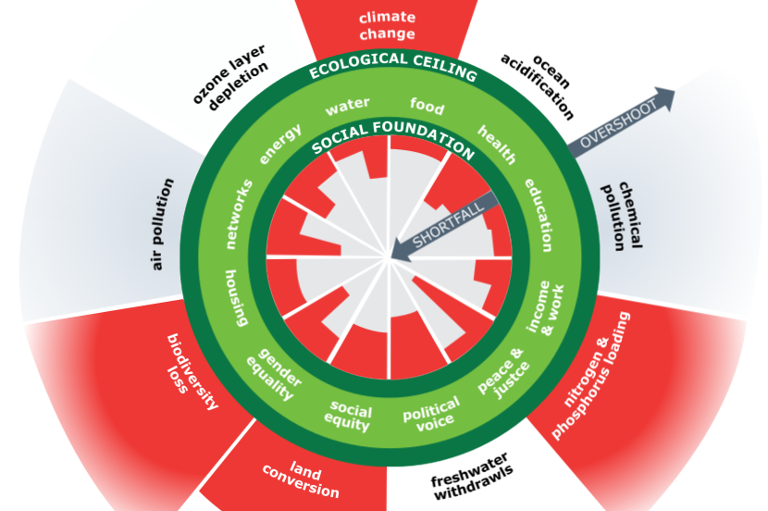

Think of the doughnut as a visual compass for how to meet the needs of all people within the means of a thriving planet. The outer circle represents our ecological ceiling, consisting of nine planetary boundaries beyond which lie unacceptable environmental degradation and potential tipping points in Earth systems. The inner circle represents our social foundation, derived from internationally agreed minimum social standards, as identified by the world’s governments in the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015. The space in between—where our needs are met and the earth’s systems are protected—is where humanity can thrive.

My inspirations include the concept of environmental space developed by Friends of the Earth in the Netherlands, and the work of ecological economist Herman Daly. Daly’s elegant diagrams showing the economy as a subsystem of Earth’s ecosystems challenged everything I’d been taught. In order to re-educate myself, I dove into ecological economics, feminist economics, complexity economics, institutional economics, and behavioral economics. I became concerned about the fragmentation across these various schools of thought, a situation that left them always at the periphery of mainstream economics. I wanted to explore their synergies in a book. And to counter the individualistic, utilitarian foundation of mainstream economics, I would start with the doughnut in order to give economics a social and ecological purpose, namely, meeting the needs of all human beings within the means of our delicately balanced living planet.

Why are images and metaphors so important to economics?

I’ve always doodled in the margins of my notes, and I liked to include pictures in reports for Oxfam and the UN. The original doughnut diagram was published in an Oxfam discussion paper I wrote in 2012, and, almost overnight, it had a significant impact. People started calling me “the doughnut lady,” and I knew there was no going back.

Following the release of the Oxfam paper, I started reading about the power of imagery and learned that over half of the nerve fibers in our brains are connected to our eyesight. We are born pattern-spotters, which is why we see faces in the clouds and ghosts in the shadows; we are constantly looking to make meaning with our eyesight. So the images we draw influence us deeply—and wordlessly.

One of my favorite guiding quotes is a line from the statistician George Box: “All models are wrong, but some are useful.” I always share this observation with my students. None of the models, including mine, are the “true” version of the world. Once we realize that, the question to ask is, are they useful relative to the values we hold? The goals we are pursuing? The context we face?

Supply and demand is still the quintessential economic image today, and it immediately throws us into the narrow sphere of market thinking. But for the ancient Greeks, “economics” meant the art and norms of household management. Who could aspire to do anything more valuable than to master the art of managing our collective household—our planetary home—in the interest of all its inhabitants? It’s time for economics education to return to its roots but adapted for modern times: it is the art of managing our planetary household in the interest of all its inhabitants.

When teaching, I begin not with supply and demand, but with a diagram called the Embedded Economy, in which the economy is embedded within society, itself embedded in the living world. And within the economy are four fundamental forms of provisioning for our wants and needs. Yes, we have the market and the state, but the twentieth-century ideological boxing match between these two meant that we lost sight of two others: the household, where we all begin every day, dependent upon unpaid caring work, and the commons, in which people come together as a community to co-create things that they collectively value. When this is our starting point for economic analysis, a far greater range of possible economies opens up.

Economics, as you often point out, originally grew out of moral philosophy. What role should morality play in economics today?

In hindsight, I was very troubled by the moral positioning of economics. During my first week at Oxford, we studied philosophy and economics side by side, discussing the concept of utilitarianism according to John Stuart Mill at the same time as we derived utility curves and supply and demand in market settings. This link between philosophy and economics was exciting, but short-lived. In week two of philosophy, the professor argued that utilitarianism is a very limited way of looking at the world, so we turned to alternative moral framings. Meanwhile, our economics studies stuck with utility theory for the following three years, leaving me flummoxed and disillusioned. Years later, I was introduced to the work of Amartya Sen, whose point of departure is not the market, but ensuring the essential capabilities of every human being. Sen’s fundamental position is that we should all have the capability to lead long, healthy, empowered, engaged lives and that economic systems should be designed to enable such outcomes.

Modern economics isn’t amoral; it does have a philosophy, namely, deep utilitarianism based on the idea that markets are the ultimate arbiters of value. But, as we know, markets only value what is priced, and they only work for those who can pay—and those are big caveats. Economics is far too often taught as though it were a positive science, not a normative one. But there are norms and values embedded at the heart of neoclassical economics; they’ve just been tucked away so deeply that we don’t immediately see them.

If economists aren’t conscious of the values embedded in the frameworks that they teach, then they’re not aware of what they’re tacitly passing on to the next generation. That alone is alarming.

What is wrong with the way economics portrays human nature and behavior?

To understand the portrayal of humanity in economics, we must go back to the nuanced arguments of Adam Smith. Smith argued that self-interest helps to make markets work, but he also recognized that our concern for others is essential to making society work. Indeed, he celebrated and championed our sense of justice, our generosity, and our public spirit.

Over time, Smith’s nuanced portrait was stripped back and simplified, resulting in the caricature we know as “economic man,” which assumes that individuals behave rationally, with complete knowledge, while seeking to maximize personal utility, or satisfaction. The more that students learn about this “economic man,” the more they say they value traits such as self-interest and competition over altruism and collaboration. Who we tell ourselves we are shapes who we become: the model remakes the person, in this case, not for the better.

Likewise, the heavy focus in economic education on the supply and demand of goods and services is a political act. From day one it places market mechanisms at the center of our economic vision. It privileges price as the metric of value, and it leaves invisible all the unpriced forms of value that contribute to a good life. If anything we value, good or bad, falls outside of a market contract, it is called an externality.

My great awakening came in my second year of economics study when I wanted to talk about climate change, acid rain, the hole in the ozone layer, and the collapse of ecosystems. To express this, economics offered two words: “environmental externalities.” In the twenty-first century to still speak of the death of the living planet as a mere environmental externality is disturbing, to say the least.

Inequality, you observe, is not an economic necessity but a “design failure.” How can we redesign the economy to produce more equitable outcomes?

Consider how economists have traditionally thought about inequality. Long ago, Vilfredo Pareto observed that 20% of people owned 80% of the wealth. The 20/80 pattern appeared in different countries, reinforcing his conviction that it was a natural phenomenon. He reasoned that if we want to expand well-being, we should invest in the rich people because they, in turn, will expand income for the benefit of all, a precursor to the trickle-down perspective embraced by conservative politicians.

In the 1950s, Simon Kuznets analyzed data on income inequality over time in the UK, the US, and Germany. He found an upside-down U-shape, indicating that inequality first increased and then decreased. Kuznets was surprised and couldn’t make sense of his finding—he had expected the rich to get richer, not the poor to catch up—and he presciently worried that his finding would become an “unwarranted, dogmatic generalization.” He was right: that upside-down U shape became known as the Kuznets curve and turned into the most influential diagram on inequality in all of economic theory.

As the curve gained traction among economists, it started to whisper a mantra of its own: if you care about inequality, don’t intervene to redistribute because you may well actually get in the way of growth, which—as the curve shows—will eventually even things up again. We’ve now lived through decades shaped by the political consequences associated with that assumption. Trickle-down economics. Austerity economics. Both are rooted in the idea that growth will yield greater equality over time, so today’s inequality must be endured.

In 2014, Thomas Piketty revisited Kuznets’s analysis with far richer data. He concluded that Kuznets was right, but that he had been studying a very unusual period: pre–World War I to post–World War II. It turns out that war destroys the capital of the wealthy and postwar governments invested heavily in health, education, and housing. This was what bent the curve down, not the inherent workings of the market. But the myth lived on for half a century.

There’s nothing “natural” about economic dynamics that lead to extremes of inequality: they arise from patterns in the ownership of wealth. We’ve got a real chance this century to change our approach to inequality by moving from redistributing income to pre-distributing the sources of wealth creation. For the first time, we have the technologies to do this. Instead of oil rigs and coal mines, we can generate energy on the roofs of our own houses, or through community-owned wind turbines. We have instant communications with near zero marginal cost of speaking with somebody on the other side of the world. We have 3D printers and shed-size machinery as opposed to massive factory-sized, industrial processes. The combination of these technologies—distributed energy, production, communications, and knowledge—is an unprecedented opportunity to democratize the sources of wealth creation and the ownership of enterprises that are the basis of such wealth creation. For the first time, we have the chance to build truly distributive economies. In a moment of often overwhelming bad news and economic injustice, these opportunities provide a basis for hope and action.

Recent years have seen a surge of interest in alternative economic paradigms, among them “degrowth,” “new economy,” and the “well-being economy.” In what ways do these overlap with and differ from doughnut economics?

These concepts are first cousins, or even siblings, of doughnut economics. There is difference in nuance, in emphasis, but overall we share core beliefs.

I don’t use the term degrowth, because in terms of framing, I think it confuses, rather than clarifies, debate. But in terms of the substance of what the degrowth movement stands for, there is deep alignment. The same is true for the well-being and solidarity economy. But I’ve learned that the name “doughnut economics” is accessible to a wide array of people who tell me they would never have picked up a book with the word “economy” in the title. Its playfulness, it turns out, is a plus.

Is this multiplicity of concepts a problem? No. Nature evolves by diversifying its options, selecting the variations that perform best, and then amplifying them. When it comes to creating a new economic paradigm, I feel we are in the diversification phase. As we struggle to escape the straitjacket of neoclassical economics, the healthiest thing we can do is diversify. I like the metaphor of a flotilla of diverse boats, some with sails, some with oars, others with engines. I’m probably sitting in an inflatable doughnut rubber ring. But we’re all heading to a similar destination.

One of your priorities is changing the way that economics is taught. How receptive has the economics discipline been?

There is, I believe, a very strong desire internationally among economics students for transformation in economics curricula, as seen in their dynamic movement, Rethinking Economics. When I speak in university economics departments, it’s usually because students have invited me: they are the ones driving change. On the other end of the spectrum are the more conservative economics professors. They can get quite emotional—upset and angry. I gave a talk at a conference recently, and a professor who was asked to respond began by saying, “As a citizen, I’m almost persuaded by you, but as an economist, I must tell you that you make a very big mistake when you antagonize economists.” I responded by noting that economists for decades have been antagonizing philosophers, political scientists, sociologists, psychologists, historians, and many others.

People often believe that it’s the older-generation economists who are the problem and that we’ll change economics “one funeral at a time.” I disagree. After a talk to academics in Belgium, one young assistant professor casually told me that he found the ideas in my book very exciting and would love to teach them, but since he was on track for getting tenure, he had to be cautious. This comment stuck with me and reinforced my belief that it’s not the people but the system that stands in the way of transformation.

I’m in the process of setting up an organization, Doughnut Economics Action Lab. One of its goals is to provide materials for high school teachers and university professors seeking to teach alternative economics, including the doughnut concept, a new view of “economic man,” complexity, and beyond-market ideas.

It will take a deep transformation of values and culture—what we call a Great Transition—to reach a future rooted in justice, well-being, and ecological resilience. How can doughnut economics contribute to such transformation?

Since the publication of my book, I have spent two years presenting its ideas to companies, cities, teachers and students, civil servants, communities, and many more. The requests have been more than I ever imagined. That gives me great heart, because it means there’s a hunger for transformational change.

But I want to move from talking to doing. As Buckminster Fuller said, you never change things by only fighting the existing reality, without building a new model that makes the old one obsolete. I’m now moving from talking about the doughnut to working with those communities that most want to put these ideas into practice. We are working with teachers to make videos and lesson plans for the classroom. We are working with cities to turn the doughnut into a tool for reimagining their futures. And we are working with companies, including the financial community, to ask what kind of business is fit for the twenty-first century.

We also are working with governments seeking to create a well-being economy, developing new metrics that move beyond GDP toward more holistic measures of progress. And we’re working with artists and performers to turn the doughnut concept into a game or a work of art—making it playful and widely accessible.

We must demonstrate that we can reinvent our economies and our businesses by putting values at the heart of a twenty-first-century economy. At forty-eight, I see myself observing younger generations emerging with new voices and ideas. I am thrilled to work with them, creating possibilities neither generation alone could have imagined as we undertake this journey of transformation.