Against the backdrop of an agrarian landscape that has become more homogenous, sterile and empty over the past 50 years, a new movement of Dutch farmers and citizens is emerging. They want to support a type of agriculture that does not damage the environment, enriches the life of farmers and citizens, and produces healthy food. This desire is expressed through a vast array of initiatives. It includes growers who allow citizens to undertake their harvesting, dairy farmers who plant trees and herbs in the field, cereal farmers who sell directly to local bakers, farms in which citizens become shareholders, and many more.

These initiatives spring from both new farmers without a history in farming as well as established farmers who choose to chart a new course and do things differently. Together, these different initiatives come together in what is known as ‘agroecology’. Agroecology is a broad term that encompasses elements of food production, processing and distribution. It is a daily practice based on traditional and new knowledge of the entire agro-ecological cycle and its many complementary interactions. These interactions between people and nature form the basis for continued innovation. It is thanks to these innovations that we can enjoy our rich diversity of vegetables, grains, livestock, fruits and dishes.

Agroecology stands in contrast to an industrial agricultural model in which growth is based on the prescriptions of the scientific establishment and a technological treadmill of chemical inputs. In agroecology, the knowledge, resources, and wishes of farmers and citizens are foregrounded. Agroecology also prioritizes shorter food chains and local/regional markets in which values such as cultural taste, landscape preservation, strengthening local communities, animal welfare, and health all play an important role. In this way, agroecological initiatives respond to the societal demand for a more sustainable, just, and social form of agriculture.

Despite this wellspring of new initiatives, the burgeoning agroecology movement in the Netherlands also faces a number of challenges, not least the difficulties in gaining secure access to land. In this longread, we explore the land politics behind developments in Dutch agriculture, the challenges and opportunities this presents, and the ways in which agroecological initiatives are reacting by developing alternative markets, values, and understandings of ownership and property.

Developments in Dutch agriculture

Dutch agriculture has changed considerably over time. Until the 1950s, Dutch agriculture was mainly characterised by small, mixed livestock and cereal farms. Average farm size was no more than a few hectares and often comprised multiple parcels of land spread out from one another. This changed after the Second World War following the Dutch experience with hunger and food shortages. It was considered imperative to ensure food security by boosting agricultural production. So begins a long series of reforms of Dutch and European agricultural policy, ultimately leading to the Dutch agricultural system that we know today.

The Dutch government believed that in order to achieve national food security, it was vital to support the emergence of an efficient, competitive and ‘modern’ agricultural sector. This was to be achieved by programmes of land consolidation as well as a series of measures to bolster production and exports, including minimum prices for key agricultural products, tariffs on imports, and compensation schemes for exports. Starting in 1956, the government also invests in agronomic training in modern (industrial) farming techniques, believed to be superior to traditional farming knowledge passed along through families over generations. Farmers who could not adapt, or were pushed out due to farm size expansion, were stimulated by the government to emigrate to countries such as the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

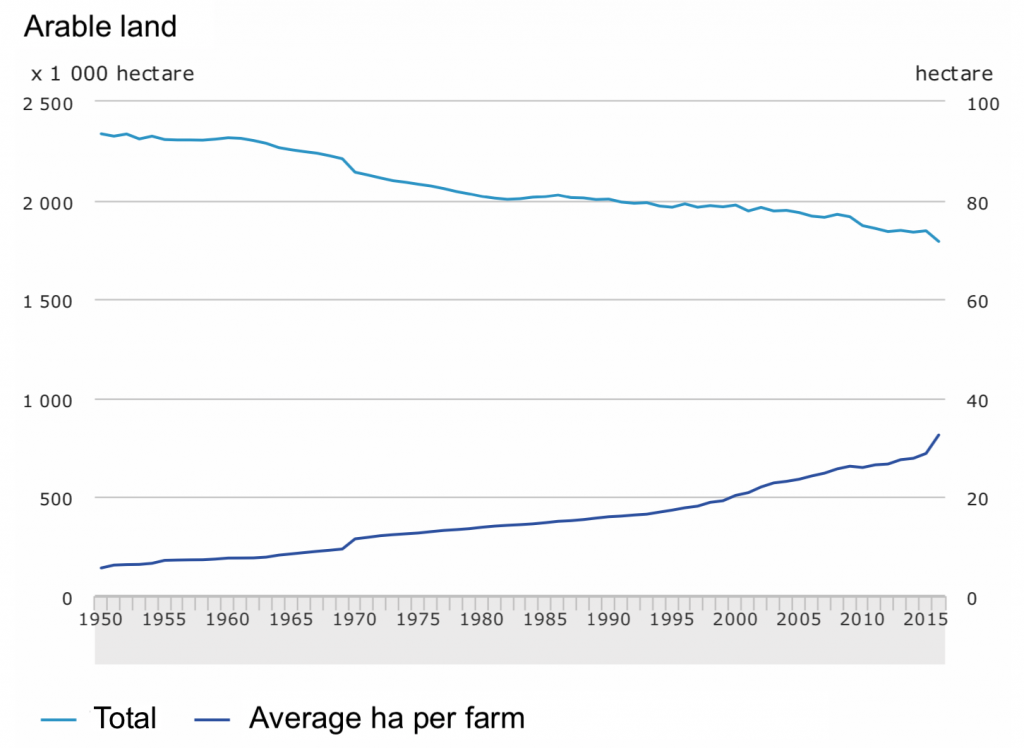

As a result of these measures, the average farm size in the Netherlands steadily grows, with the biggest growth observed in cereal and dairy farms. The livestock sector also expands significantly with the average herd size of cattle farmers increasing from 13 in 1950 to 160 in 2016. The number of intensive livestock farms (categorized as those with over 250 cows) increases from 44 farms in the year 2000 to 511 in 2016. At the same time as farms expand, intensify and consolidate, the total utilized agricultural area (UAA) decreases due to urban sprawl, and to a lesser extent, environmental measures. This leads to an increasing concentration of farmland.

Figure 1. Evolution of farm size and UAA over time

Source: Toekomstboeren

In the 1980s, Dutch agricultural policy shifts from import protection and price supports to a more free market model geared towards the production of cheap food and partial compensation. The agricultural processing industry grows and exports increase rapidly as Dutch and European policy incentivises (multinational) agribusiness instead of production for domestic and local markets. The export value of Dutch agricultural goods stands at 44,6 billion euros in 2017, marking it out as a strategic sector for the Dutch economy.

These reforms have a strong impact on farmers, nature, and society. While Dutch agriculture is booming, the prices that farmers receive for their products have lagged behind as food has become increasingly cheap. Today, people in the Netherlands spend on average 11% of their income on food compared to around 25% in 1970. At the same time, costs of production have shot up as farmers have to expand, mechanise and intensify in order to keep up. This has resulted in a huge pressure to produce more if they wish to make a reasonable living. A significant number fall behind: it is estimated that as high as 20 – 40% of farming households are struggling along with an income under the officially registered low-income threshold.

As a result of this ‘cost-price’ squeeze, many Dutch farmers are increasingly reliant on loans from the bank leading also to a situation of high indebtedness. In 2012, the total Dutch agricultural debt was estimated at 42 billion euros – or 60,000 euros per farmholding. These debts are the cause of significant stress amongst farmers, leading many to give up and decreasing the appeal of farming for the next generation. This is reflected in the dwindling number of farms in the Netherlands which has fallen from 410,000 in 1950 to just 55,000 in 2017. In the past 35 years, the number of farms has halved. On average, 6 farmers exit agriculture a day. This is a trend that appears set to continue: of farmers older than 55 years of age, just 40% has a successor.

The developments in Dutch agriculture have also had negative impacts on the environment and on nature through the introduction of machines, agro-chemicals, synthetic fertiliser and veterinary antibiotics. Agro-chemicals are responsible for 25% of groundwater pollution while just 15% of indigenous plant and animal species remain and soil fertility has decreased by 55%. The intensification of production methods has also heightened risks for both animal and human health. In the past two decades, the Dutch livestock industry has had to deal with multiple outbreaks of animal diseases including swine fever, foot and mouth disease, Q fever, and birdflu. Several people have been ill and died as a result of Q fever.

While the Dutch government, in alignment with the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy, has introduced a number of measures to try and mitigate some of these negative effects, many of them are sector specific and are ill-adapted to grapple with the realities of mixed and diverse farming systems. They fail to address the underlying drivers related to a toxic production model and as such are more about combatting symptoms, rather than root causes.

Land tenure and use

Like the agricultural sector as a whole, Dutch farmland has also been liberalised over the past decades. This has had a number of effects as the market exchange value of farmland has increased and processes of financialisation have crept in.

Previously, the Dutch land lease law was quite regulated, setting a minimum duration for freehold lease arrangements of 6 years as well as an automatic extension of the lease period and a maximum lease price. This offered considerable benefits to the lessee but was less attractive to the lessor. In 1995 and 2007, new, more liberal forms of lease were introduced. This has resulted in an increase of (very) short-term lease contracts. This has made land more easily available (also for small and medium sized farmers), but it leaves farmers far less protected than before, making it more difficult for them to invest and develop a long-term business plan.

Between the 1940s and 60s, there was also a set of rules and regulations in place with respect to buying and owning land, including a temporary price stop and other controls. Today, the land market is fully liberalized with no specific policy on land prices. This has led to a surge in farmland prices: farmland prices have increased over 4.5 times between 1963 and 2018. This has made it much harder for farmers with fewer economic resources to buy farmland while for new entrants and young farmers it is near impossible.

One of the effects of the liberalisation of the market in agricultural land has been rising land concentration: the capturing of control over an ever increasing share of farmland by ever fewer hands. This is a common trend over the past decades throughout Europe where just 3% of farms control 52% of EU farmland.1 In the Netherlands, land concentration is expressed by a declining number of small farms and a growing number of large farms such that in 15 years, between 1990 – 2015:

- The total number of small farms (under 10 hectares) declined by 56%, from 59,310 farms to 26,190 farms

- The total number of large farms (over 100 hectares) increased 3.5 times, from 690 farms to 2,390 farms

Concentration of land in the Netherlands is in large part the result of larger farms buying up land from smaller holdings. This allows them to expand and take advantage of economies of scale in order to lower the unit costs of production. Farming enterprises that do not participate in this competitive cycle can face bankruptcy, bringing yet more land to the market to be accumulated by a small number of larger businesses. Without proper regulation in place to ensure that land remains available for small and medium farms, this risks setting off an inevitable and never ending process of concentration.

Land in the Netherlands is also increasingly seen as an attractive object of investment by non-agricultural actors. The largest private landowner in the Netherlands for example is the insurance company ASR which owns about 40,000 ha of land. While land is deeply embedded in the financial system through the extension of credit loans and mortgages in which land serves as collateral, new forms of financialisation have emerged following the 2008 financial crisis with farmland increasingly viewed as a safe haven for capital accumulation. This can have negative effects on volatile land, food, and agricultural commodity markets and unleash speculative tendencies.

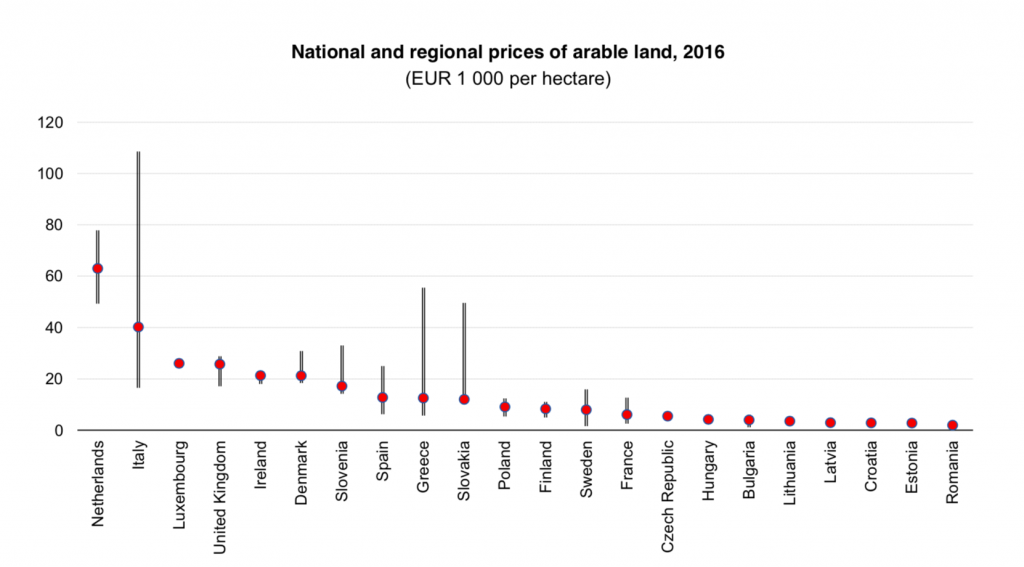

These tendencies can drive up the price of farmland in a context whereby land in the Netherlands is already amongst the most expensive in all of the EU. The price of farmland in the Netherlands varies between 40,000 and 80,000 euros, with an average purchase price of one hectare of arable land of 63,000 euros in 2016.

Figure 2. Land prices in the EU

Source: Eurostat, 2018

As land becomes an increasingly attractive investment and object of speculation, the landmarket becomes ever more competitive with different actors vying to buy up land. This can also trigger processes of land use change, as converting land from agricultural to non-agricultural use can drive up the price by as much as ten to twenty times. This is particularly the case for farmland situated on the outskirts of urban centres where pressure on land is often at its peak and the temptation for developers and investors to buy up farmland only to sell it off later at a much higher price is very great. In the absence of proper spatial planning and zoning policies, as well as other measures to protect farmland, this can lead to a significant loss of farmland and the abandonment of farms.

A relatively more recent development in the Netherlands has been the buying up and lease of farmland by investors for the installation of solar energy projects.2 These projects can be expected to increase as the Netherlands has been identified as the worst bar one performing EU country when it comes to renewable energy generation. The Energy Research Centre Netherlands (ECN) for example estimates that by 2050, approximately 0,5% (10,500 ha) of Dutch farmland will take on a dual agrarian and solar energy function if the goals contained in the Paris Climate Agreement are to be reached.

Land for agroecology and new farmers

Despite the difficulties that farmers are facing in the current land and agricultural system, there is a growth in a number of new approaches, such as agroecology. Agroecology involves a different form of agricultural production, processing and distribution: one that seeks progress in the strengthening of local resources, markets, and knowledge and in a different relationship with nature and with citizens. This stands in contrast to other, more conventional forms of agriculture that prioritise external (chemical) inputs, prescribed knowledge, and global value chains. In agroecological systems, there is an emphasis not just on food production, but also other values such as landscape preservation, biodiversity, a living countryside and nature.

In the Netherlands, agroecology encompasses a number of different movements including circular agriculture, biodynamic farming, permaculture, community supported agriculture (CSA), vegan farming, food forests, and regenerative agriculture. Exact figures on the size and scale of these initiatives are difficult to come by but all indicators point to a growth in their number:

- Between 2013 and 2017, the number of organic farms increased by 14,6%.

- In the past 10 years, the number of CSAs has grown from less than 10 to over 90 farms.

- The number of farms that engage in direct selling, processing, and on farm education has risen between 2008 – 2016 by 17%, 5%, and 84% respectively.

The growth in agroecological initiatives is the result of both conventional farmers deciding they want to change their agricultural practices and new farmers who want to engage with a new agricultural movement from the outset. A survey conducted by the Dutch small farmers organisation Toekomstboeren has brought into relief the profile of some of these new farmers engaging in the agroecology movement. It finds that these farmers are generally speaking relatively young (54% are under 40, 26% are between 40-49, and 29% are over 50) and majority (55%) women. In addition to a passion for farming, many are motivated by an effort to advance a more social and sustainable form of agriculture:

“I want a business that is people-centred. I like to have people on my terrain.”

“We want to live from the land and share this simple richness with others”

“I feel happy, free and blessed that I can live from the land in harmony with nature. I can see from the increase in biodiversity, in the growing numbers of butterflies for example, that nature benefits from the right kind of cooperation”.

These ideals are often difficult to combine with participation in the mainstream food market. Many of them therefore choose to develop alternative marketing channels such as farmshops, box delivery schemes, or self-harvesting by consumers. Consumers who engage in these marketing channels often share the values of agroecology and are therefore prepared to pay a higher price for their produce. This in turn allows agroecological farmers to make a living.

Still, many of these new farmers express the need for support in acquiring land, practical agroecological knowledge, marketing channels, processing activities, and starting a new business. Despite the significant social and environmental benefits that agroecology offers, these initiatives receive very little – if any – financial or other support from current national or EU agricultural and rural development policy frameworks. Not surprisingly then, 84% of farmers interviewed in the survey indicate that agroecology deserves a stronger representation in policy formation and decision-making processes.

One of the biggest obstacles for new farmers is access to land. For the majority of new farmers, buying or leasing land via the regular land market is simply too expensive. They must seek out other ways, including leasing land from environmental organisations, local or regional authorities, estates, or other farmers. Another option is to enter into the operation of an existing farm.

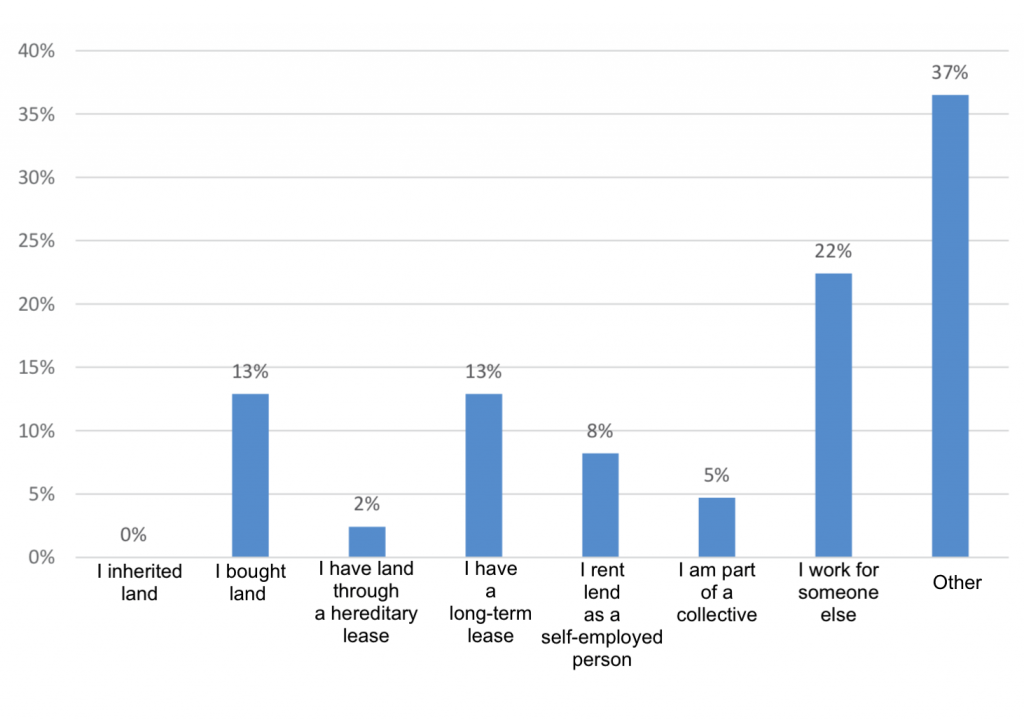

It is not just gaining access to land, security of tenure is also an issue. A series of meetings organized by Toekomstboeren reveals that tensions can frequently arise between a farmer and the landowner. In cases of conflict, the farmer often has to leave that same year. This also holds true when councils change their land use and allocation plans. The precarity of many new farmers is also demonstrated by a survey undertaken by Toekomstboeren which shows that only 13% of new farmers own land, and only 15% have a multi-annual lease contract. The remaining 72% has a contract of less than a year or no contract at all. This makes building up a consumer base and a form of sustainable agriculture extremely difficult: farmers will be less likely to invest in their business, make improvements to the land, and to experiment with new practices if they are unsure that they will reap the rewards of their efforts.

Figure 3. Land situation amongst new farmers

Source: Toekomstboeren

In the past years, a range of initiatives has emerged that are attempting to take land out of the market. They are unified in the belief that land should not just be a commodity but should serve a social as well as economic function. Some of these initiatives advance the concept of the ‘commons’ – lands which are in the hands of communities and whose use is to be collectively decided upon.

This can take on different forms. Land trusts for example collect donations, obligations, loans, and investor certifications in order to buy land which is then managed by a trust and leased out under favourable conditions to sustainable farmers. Another form is crowdfunding. This can involve many different strategies, depending on the particular circumstances of farms and regions. In the case of the CSA initiative ‘De Nieuwe Ronde’ (The New Round) in Wageningen, consumers have collectively fundraised to buy the land of a local farmer that will be paid off by the farmer over the years. In other constructions, land becomes the property of the consumers with the farmer paying rent. In still other examples, particular farm buildings are bought up by citizens or even, as in the case of the farm ‘Veld en Beek’ (Field and Stream), ‘cow shares’ are issued to a consumer network society. The consumer network also has annual meetings where consumers have a say in the running and direction of the farm.

There is also increased cooperation between different farmer groups and between farmer networks and local and provincial authorities in order to support access to land for sustainable farming. For example, Toekomstboeren is part of a new Federation of Agroecological Farmers Organisations that is standing up for the interests of agroecological producers and helping them to access land. Another example is that of ‘Grootschalige Kleinschaligheid’ which brings together growers, cereal and dairy farmers to support one another economically, make better use of local resources, and establish spaces that are attractive for people and nature. They engage in collective lobby work towards councils and government to gain access to land for such projects.

Some provincial governments in the Netherlands are also lending a hand. The province Noord-Brabant for example stimulates sustainable agriculture by paying out 50% of the land value to sustainable farmers that are settled in the vicinity of nature areas. The province has also developed a point system for land based on a number of sustainability criteria. Sustainable farmers who meet these criteria receive priority access to land as well as a discount on their rental fees. Strikingly, the total income the province has gained from leasing out land through this system has not diminished, demonstrating also the economic sustainability of this model.

Towards system change

In the current system, land and subsidies are not allocated to those that preserve values such as clean drinking water, biodiversity, a beautiful landscape and the production of healthy food, but to those that can extract the most money from the ground. This is often incompatible with sustainable land use. This system is not inevitable but is the result of policy choices that reward economies of scale and liberalization. This forces farmers to practice a particular type of agriculture that goes against soil health, animal welfare, climate justice, landscape and nature conservation – values that are not captured in the market price of land and therefore disadvantages those farmers who do take them into consideration.

Instead of transitioning towards a more diverse and resilient agricultural system, current policy only seems interested in tackling the symptoms of this failing model and mitigating the worst effects of industrial agriculture. This acts as a block on allowing agroecological innovations to flourish.

Despite these difficulties, the initiatives of new and agroecological farmers in the Netherlands demonstrate that it is possible to do things differently. They are circumventing the market by working with collective forms of property, directly connecting farmers and citizens, and developing agricultural practices that bring people and nature together. In this way, values other than just profit play a role in shaping the production, processing, and distribution of food.

However, much of their success is still dependent on the many long hours that these farmers are willing to put in and the good will of citizens to pay more to support the values behind these initiatives. Let’s therefore support the agroecological movement in all its diversity: with farmers, citizens, environmental activists and scientists showing how we can work towards an agricultural system that is colourful, resilient, and enriches nature, society and the farming community.

Toekomstboeren (‘farmers of the future’) is an organisation run for and by new farmers in the Netherlands. Toekomstboeren are those farmers that are interested in going beyond the confines of conventional agriculture and engage in creative and innovative thinking. www.toekomstboeren.nl

Acknowledgements

A Dutch report, upon which this longread is based, entitled ‘Grond Van Bestaan’ can be found here.

Translation and editing by Sylvia Kay.

About the Land Strategies partnership

This longread forms part of a Strategic Partnership about innovative land strategies and access to land for agroecology in Europe. Partners in this project include Eco Ruralis, European Coordination Via Campesina, IFOAM EU, Real Farming Trust, Terre de Liens, Transnational Institute, and Urgenci.

Strategic Partnership – Land Strategies – 2018-2020

Disclaimer: This longread represents the research and opinions of the organisations that have authored it. The content is the exclusive responsibility of the respective authors. The European Commission is not liable for any use that is made of the information contained within.

Disclaimer: This longread represents the research and opinions of the organisations that have authored it. The content is the exclusive responsibility of the respective authors. The European Commission is not liable for any use that is made of the information contained within.

Explanatory notes

1 For further statistics on the scale of farmland concentration in the EU, see TNI’s ‘Land For the Few’ infographics.

2 These renewable energy projects are not without controversy and have been described by some as a form of ‘green grabbing’. See here for example for a discussion of a contested photovoltaic energy project in Sardinia.