A few weeks ago I walked into a bar in San Jose, California. The power in my neighborhood had just been restored after being shut off for two days by a PG&E-instituted series of rolling blackouts to minimize the risk of their aging power lines being knocked down by windy conditions and potentially sparking another massive wildfire.

It was a dry and unusually warm night for October, and I could smell the subtle scent of smoke in the air, potentially from one of the many blazes currently burning around the Bay Area. As I scanned the draft list for something to drink, my eyes were drawn to a beer brewed by Shady Oak Barrel House, a brewery based out of Santa Rosa, California. I wasn’t really feeling like a pale ale, but there was no way I wasn’t ordering this beer — if only so that I could say its name out loud. “I’ll take a ‘F*ck PG&E.’”

It’s no surprise that northern Calfiornians are disaffected with the investor-owned electric utility. They’ve been found culpable for gas line explosions, for some of the state’s deadliest and most destructive wildfires, for diverting safety money toward profits and executive bonuses, and — most recently — for a grossly mismanaged series of intentional blackouts that impacted millions in the Bay Area alone.

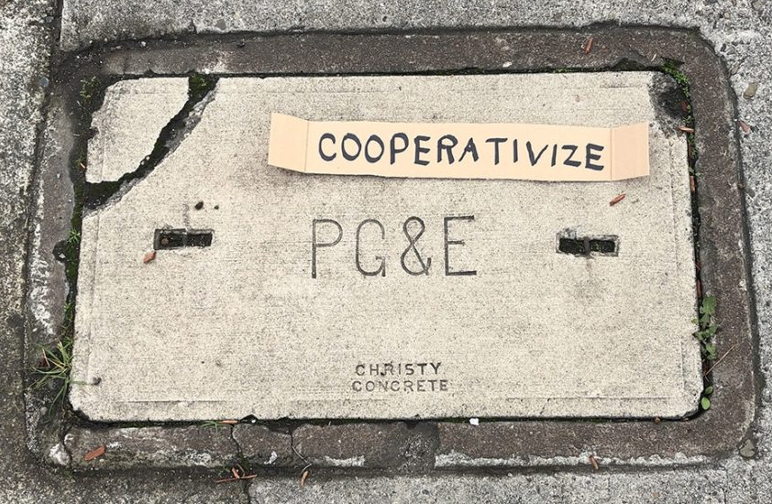

But if there’s a silver lining to the PG&E disaster, it’s that — in the midst of filing for bankruptcy — they’ve opened up the space for conversations about alternatives. And perhaps one of the most interesting of these conversations is based on the idea of transforming the utility into a network of cooperatives: utilities owned and managed by the ratepayers themselves. It’s an idea that’s being discussed by the mayors of 22 California cities including San Jose, Oakland and Sacramento, and although it might sound a bit far-fetched, there are actually many precedents for it.

“The history of co-ops in the electricity sector is fascinating,” Johanna Bozuwa, co-manager of the Climate & Energy Program at Democracy Collaborative told Shareable. “They go back as far as the 1930s, during which a key tenet of the New Deal was to provide access to electricity by creating the rural electric co-op model that continues to provide energy today.”

There are, in fact, over 900 rural electric co-ops operating in 47 states providing electric service to 56 percent of the U.S.’s landmass. And, according to Bozuwa, many of these were started during the New Deal.

Electric co-ops work pretty much the same way as an investor-owned utility like PG&E, except instead of being owned by shareholders, it’s the ratepayers — the people actually paying for and using the electricity — who are the owners.

“The shareholder, in the case of a cooperative, is you and your fellow community members,” Bozuwa explains. “So that means that at the end of the day, electric co-ops are supposed to be beholden to their customers. Any of the revenues or benefits are supposed to benefit the customers.”

This is very different from an investor-owned utility model which is looking to return profit to investors. It means that an electric cooperative does not have the same incentives that PG&E has in terms of diverting money away from infrastructure investment and toward executive bonuses.

Another benefit of electric cooperatives is that they run on the principle of democracy. That means that unlike with PG&E, which operates on the traditional business structure of a top-down hierarchy, the electric co-op model gives ratepayers democratic control of their utility through a radical concept that you might have already heard of: voting.

In practical terms, if the executives were — for example — working to sow disinformation about climate change, and were promoting climate denialism, as PG&E was doing as early as the 1980s, ratepayers could simply vote them out. Or, if funds meant to be reinvested back into the grid were instead spent on executive pay raises, those executives would probably be out of a job fairly quickly.

When the profit motive is stripped from the equation, a lot of interesting things begin to happen. For example, PG&E has absolutely no incentive to lower their rates — in fact, they have every incentive to increase them, since that means more money in the pockets of shareholders. But when ratepayers are the shareholders, the goal is to keep rates stable, or even to lower them.

“Electric co-ops are better situated to not exploit ratepayers in the same way that investor-owned utilities do,” Bozuwa says. “One example of this is the Wichita Electric Cooperative. They were one of the first utilities to actually lower their rates, and that was because they invested in renewable energy.”

The incentives in a co-op are shifted away from profit and toward reliability, which opens up a space for these utilities to really explore innovative ways of creating a reliable energy system for their communities. That means reinvesting money into the grid and also investing in renewables.

“Another good example of an electric co-op that’s thinking about its role to its customer-owners is Kit Carson Electric Co-op, which has made the commitment to be 100 percent solar powered during the day by 2022,” Bozuwa says. “They’ve made large structural changes to how they operate so that they are coherent with the realities of climate change.”

And here’s where things start to get really interesting. The Kit Carson Electric Company is going beyond just solar energy — they’re also thinking about what other needs their community has. For instance, providing access to broadband, which is actually a major issue in rural communities.

The Nine Star Electric Co-op in Indianapolis, Indiana is doing the same thing — except not only with broadband, but also with drinking water. The co-op, which also serves a rural area, has taken over a municipal water district and has begun getting clean drinking water into their community.

“The PG&E crisis presents to us not just a crisis of electric utilities, but an opportunity for a truly publicly oriented utility as a whole,” Keith Taylor, a co-op specialist at UC Davis told me. “So we’re talking electric, broadband, water, wastewater — the co-op model gives us some best practices that are not baked into public policy yet.”

Because most of the electric co-ops in the United States serve rural communities, they have a history of working in very challenging service territories, which has led to the development of innovative solutions to a wide variety of challenges.

“Every time the electric co-ops run into a challenge, they have figured out a way to overcome it,” Taylor explains. “And they don’t just go off and do this by themselves. Instead, they often work with one of their federations to come up with a solution that benefits not just them, but dozens of other electric co-ops. So what this means is that each individual electric co-op has a whole tool box that they can dip into to make themselves far more resilient.”

It’s through these integrated networks and federations that we can see how the co-op model might begin to solve the problem of scale, which is an important consideration when it comes to distributing energy or other public utilities.

“Where the performance really comes out is when you step back and you look at each individual electric co-op, and realize that they’re in a network system — that’s where it gets really exciting,” Taylor says.

And, there’s more to an electric utility than just its power lines. For example, Touchstone Energy is a national network of over 700 electric cooperatives, spread out over 46 states. It provides resources and leverages partnerships to help its member cooperatives and their employees better engage and serve their members. National Information Solutions Cooperative (NISC) is another example of a federation of electric co-ops which provides IT solutions for 845 energy and telecommunications co-ops in all 50 states.

“With basically any kind of service, you find that an electric co-op shares the service with another co-op. They try to form a second tier co-op to aggregate and to build economies of scale,” Taylor says. “So you’re actually able to take local control and scale it, which I think is something that’s always been a conundrum. How do you scale local? Well, electric co-ops actually give us an amazing vision of what scaling local could look like.”

As cities like San Jose and Oakland begin to explore the electric co-op model, they are going to run into many challenges, particularly from PG&E, which exerts a significant amount of political control in California.

“Even Gov. Newsom has had hundreds of thousands of dollars in PG&E campaign contributions,” Bozuwa told me. “PG&E does a significant amount of lobbying and they are a major political force in California and have even captured the California Public Utilities Commission.”

Still, the idea is gaining steam — especially since San Jose mayor Sam Liccardo was able to raise support for PG&E’s mutualization from more than 20 other California mayors, including from Oakland, Berkeley, Sacramento and Stockton. The mayors are pressuring Gov. Newsom and the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) to seriously consider transforming PG&E into a customer-owned co-op before going ahead with a bankruptcy reorganization plan.

In a letter addressed to the commission, Liccardo and the other mayors urged the CPUC to approve their plan, citing higher rates caused by the burden of paying dividends to shareholders — as well as their lack of focus on maintenance and repairs — as important reasons why it makes sense to mutualize PG&E.

The San Jose plan demonstrates that people are ready for a major shift in the conversation around the for-profit model of utilities in California, and it could very well be the first step in a movement that spreads across the entire state.

Of course, San Jose could have simply chosen to bring PG&E under municipal control, something that has been proposed by many Californian cities as well. But there are some key problems with municipalization. Namely, if cities begin to municipalize their grids piecemeal, more rural communities will be left with skyrocketing rates. This is because it is much more expensive to build power lines through more remote areas. But since PG&E has a monopoly over both cities and rural areas in northern California, this burden is distributed evenly, meaning city ratepayers are ultimately subsidizing the costs for rural ratepayers.

Cooperativization could avoid this problem, however, by creating a system of federated cooperatives that all work together, potentially mitigating the issue of higher costs in certain areas by bringing a larger part of the grid into community ownership.

“By taking over in a cooperative manner instead of a municipality pulling itself off of the grid, San Jose could help spur a movement to bring a larger part of the grid into community ownership,” Bozuwa explained. “And this is significant because there is power in numbers — there is power in having multiple communities that refuse to continue to work with PG&E.”

The future of energy in northern California is still very much uncertain. But as I sat sipping on my “F*ck PG&E” ale, I realized that what’s not uncertain is the collective revulsion towards PG&E in California right now. But ultimately, the problem is not just PG&E as an individual bad actor — it’s a structural problem. It’s a failure of the profit-motive, of privatization, of monopolization, and — ultimately — a failure of a capitalist economic system that encourages all of these misguided and dangerous tendencies. And if the public is able to progress from their anger at one company toward a more systemic analysis – one that understands the root causes of PG&E’s failures — then perhaps this moment of frustration could lead to a movement for real, structural change.

This article is cross posted with permission from Shareable.net.