Scientists tend to fall into one of three camps.

They consolidate knowledge, perform great technical feats, or explore a new vision with the boldness of a Basquiat.

Crawford Stanley “Buzz” Holling, one of the world’s great ecologists, did all three.

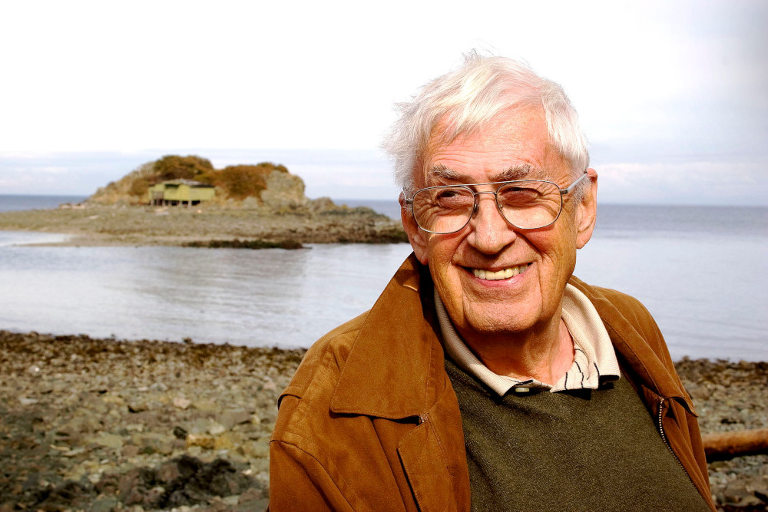

He died in August at the age of 89 in Nanaimo.

You probably didn’t hear much about the passing of this scientific visionary. Let’s be honest: Canada, a mining republic, isn’t all that fond of ecologists.

But every Canadian should know something about Holling, because his revolutionary work explains why ecosystems and civilizations collapse, and why our time is marked by increasing turbulence.

He also believed that our complex, high-energy-consuming society was on the verge of major shakeup or worse, what he called a “deep collapse.”

A deep collapse, for example, is a forest burned by wildfire and then desiccated by drought, pancaked by climate change. In the end there is no cycle of renewal, because the forest ceases to be a forest.

“This is a moment of great volatility and instability in the world system,” Holling told Thomas Homer-Dixon in an interview a decade ago.

“We need urgently to do what we can to avoid deep collapse. We also need to figure out how to exploit the opportunity provided by crisis and collapse when they occur, because some kind of systemic breakdown is now almost certain.”

Holling, a genial man, had an illustrious career.

In many respects he followed the instructions for a good life described by the poet Mary Oliver: Pay attention. Be astonished. And talk about it.

He spent his youth in the boreal forest of northern Ontario, and it remained one of his most important tutors.

Throughout his life he studied everything from the very small (beetles) to the very big (forests).

As a young researcher he worked for Canada’s Forest Service and later taught at the University of British Columbia and Vienna’s International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis. In the latter part of his life, he studied the decline of the Everglades at the University of Florida.

But to most scientists Holling is generally regarded as the father of resilience thinking.

Everybody from the digerati to economists to politicians now bandy about the term “resilience” without understanding what it really means. It has become a buzzword.

Holling basically defined the term as the ability to recover from wild shocks or the unexpected, such as a storm of bark beetles or budworms.

Natural systems are most resilient when they showcase a lot of diversity — something our economic monocultures ignore.

A wild forest can absorb many surprises from fires to insects, for example, because its diverse ecosystem ensures robustness over centuries and allows for collapse and renewal.

In contrast, human-managed forests tend to be big, dull, short-term pathologies where fires and disturbances are banished. Humans design things to exist in a steady state because we detest volatility, let alone variability. In short, we make things fragile.

In fact, that was the finding that most surprised Holling. After studying predators, forests, fisheries, lakes and swamps, he learned that they all shared the same properties.

A forest occupies a limited range for stability and constancy. Once a lodgepole pine forest reaches maturity, it is ready for a fire or a typhoon of bark beetles: collapse and renewal. And once a fir forest ages, it too is ready to be taken down by clouds of budworms.

A lake can support blue waters and lots of fish until industry and agriculture flush it full of nutrients. Then it erupts into a bloom of toxic algae, during which low oxygen conditions smother the fish. Even the plankton species change.

In many ways, Holling affirmed the old ways of thinking about the cycle of life. The myth that everything sought out some straight line of balance like a high-wire act was just that, a myth. Things can and do reach a breaking point and flip. Moreover, returning to that original state can be damned difficult.

To Holling, the big problem with human-engineered systems such as managed fisheries was that they removed resilience or flexibility from equation, the way a toddler withdraws blocks from a toy building before it crashes.

That’s why Holling helped to found the Resilience Alliance, a research group that explores “the dynamics of complex adaptive systems,” nearly 40 years ago.

He always thought that 10-year-olds understood the mechanics of overcoming adversity better than a rigid 50-year-old. You don’t have to explain resilience to a child, but governments and economists still require conferences, complex diagrams and foreign vocabularies.

Holling’s research radically revived an ancient view of nature. Unlike some environmentalists, the ecologist didn’t think the natural world operated like a steady-state Disneyland.

In Holling’s universe, tragedy, wonder, poetry, loss and instability punctuated natural life with unpredictable oscillations. There are surprises, some slow and some fast, and not all agreeable. He realized that societies and landscapes couldn’t have beauty without death, or greatness without tragedy.

Holling also understood that the natural world never really occupied a steady state or favoured “a balance.” It was always teetering or evolving from interlocking cycles of persistence and extinction, growth and collapse, constancy and renewal. He found that nature enjoys living on the edge, much like an extreme sports enthusiast.

Predator-prey cycles illustrated the dynamic. Cougar populations will swell with lots of deer and then crash. It can be a chaotic waxing and waning.

Humans generally have no idea where the edge lies in engineered environments, let alone natural ones, and they don’t want to admit their ignorance, wrote Holling.

Our attempts to engineer stability usually end in disaster, where either managed natural systems or human ones tip too far, much like the great cod collapse. We ignore small changes that inevitably lead to earth-shaking change that happen as quickly as a wolf kill.

Holling thought that human civilizations resembled a complex raft on water that could suddenly turn over, soaking or drowning the occupants.

Forests, lakes and climate can flip from stability to volatility in a heartbeat, he noted.

To Holling, an aging forest dominated by mature spruce or pine resembled a rigid global financial system controlled by a few banks or a state dominated by several corrupt political parties: “It is an accident waiting to happen.”

Holling also appreciated what Darwin observed: it is not the strong or the smartest that survive. It is simply those animals most responsive to change.

Holling worried a lot about climate change because he understood that living things managed the atmosphere, and that carbon pollution from fossil fuels had destabilized that system.

“If as is entirely possible, unexpected processes suddenly flip the system so that the changes occur much more rapidly, we will be in difficulty,” he told Alternatives Journal nearly a decade ago. “And we will need the most ebullient and powerful ways of inventing and resisting the forces that prevent or slow invention.”

The best outcome just might be an economic collapse first, he said.

“If the collapse occurs in a dramatic and extensive way so that the economic system can become partially disengaged, then the intensity of economic impact on the environment will weaken. But one hopes for something deeper, an integrative understanding and approach to the way that humans relate to the world, and the way the world relates back to humans.”

In an interview with Homer-Dixon, the ecologist explained why he felt the world was on the verge of a crisis.

Given the cyclical nature of life and engineered systems, “collapse is usually part of the story,” Holling said.

Second, he thought that the “rapidly rising connectivity within global systems, both economic and technological, increases the risk of deep collapse. That’s a collapse that cascades across adaptive cycles, a kind of pancaking implosion of the entire system as higher-level adaptive cycles collapse, which causes progressive collapse at lower levels.”

“The collapse doesn’t have to start at the top,” he added. “It can be triggered at the microlevel or the macrolevel or somewhere in between.” He knew that small things tended to bring down bigger systems.

His third reason of concern was “the rise of mega-terrorism,” which increased the risk of major disruptions in world systems.

“I’m not sure why mega-terrorism has become more likely now,” he said. “I suppose it’s partly a result of technological changes and the rise of particularly virulent kinds of fundamentalism. But I do know that in a tightly connected world where vulnerabilities are aligned, such attacks could trigger deep collapse, and that’s particularly worrisome.”

Holling thought there was only one way to approach the growing volatility and unpredictability of faltering economic empires and dying ecosystems. “One cannot predict what the future holds,” he often said.

As a consequence, he felt people had no choice “but to act inventively and exuberantly” by creating experiments and adventures in different ways of living. ![]()

Teaser photo credit: Photo via Simon Fraser University’s Flickr, Creative Commons license CC BY 2.0.