Lino Pichasaca and I walked the rough footpaths, the chakiñanes in Kichwa, around the Hacienda Guantug in the province of Cañar, Ecuador. It was 1967, and the Ecuadorian agrarian reform was getting started. Leaders like Lino saw great possibilities and huge obstacles. We walked past the fields evaluating the crops and talking to people nearby. We visited people in their houses, attended meetings, and planned.

Lino told me what he saw for the future, what he wanted to happen, and what the people wanted to make happen. The people needed schools. The children playing around the adobe houses would grow up to be the teachers. The communities needed experts, technicians, doctors, business leaders, and scientists, and they would all be from the indigenous Kañari community.[1]

He pointed to children chasing each other in the dust, and said, “This one will be an agronomist, this one a veterinarian.” He explained that the community had to supply its own experts to guide them to development, or their alternative to development, on their own terms. They do not want others to come in and tell them what to do and what kind of future to live in, he said. This will be decided by Kañaris on Kañari terms.

A meeting during the course on cooperatives in the abandoned house of the Hacienda Guantug. Right to left, José Zaruma, Mariano Zhinin, Lino Pichasaca, Antonio Quinde. Peace Corps Volunteer archives.

Lino was a Kañari leader from the Cañar village of Quilloac. The ethnic Kañari have lived in the high Andes of southern Ecuador for thousands of years. They built their traditions and culture over time. They suffered conquest by the Inca, and can still tell you why they didn’t like that. When I walked the trails with the people, they showed me where the Inca came the first time, and where the Kañari chased them away.

Then they suffered a double conquest by the Spanish and the abusive hacienda system that followed. One young man showed me the road that the Spanish used when they came in. “We didn’t know they would be worse than the Inca,” he explained. The Inca took away the Kañari independence and their sacred power sites, and they organized every detail of their lives, but the hacienda system brought cruel abuse, deprivation, misery and hunger.

The Kañari lost their freedom and their ability to make and act on their own decisions. But they did not lose their hope, or their culture, or their worldview. At the time of my visit in the 1960s, the agrarian reform gave them the opportunity to be free and determine their own future.

As we looked down on the valley from the high trail to the páramos, the high grasslands, Lino told me of his hopes and what he dreamed of. Then he added the fear that petty jealousies, abused soils, lack of education, corruption in the agrarian reform agency, racism, and poverty would make success impossible. Lino, like many leaders, could see the whole picture, the good and the bad, and carefully prepared for both.

Before irrigation came to Cañar in the 1990s, the ground was bone-dry for most of the year. (Archivo Cultural de los Cañaris/Preston Wilson)

There were other leaders, too, that I had long conversations with on those rough trails. They were the ones who worked against all odds and who faced great dangers on the outside chance that they would find some success. Pío Alberto Culala, from the village of Shuya, walked from community to community, from house to house, to convince campesinos, one at a time, to join the cooperatives. He taught cooperative law and agrarian reform law as he learned it, studying by his kerosene lamp. Other leaders also showed by example that the indigenous people could stand up to hacienda owners and local officials and demand their rights as equals: Juaquin Lala, Manuel Sinchi, Mariano Zhinin, José Buñay. They are gone now, but the generation living now in freedom and equality that they take for granted owe more to their grandparents than they can ever realize. Some are still leading the community, such as José Antonio Quinde, who has not lost his fire.

Participants in a course on cooperatives, 1967. Front left, Mariano Zhinin, Isidoro Guamán Quinde on his left. Right front, Lino Pichisaca next to José Zaruma. Back row, Jaime Pastuizaca left of Anthony Quinde, Luis Salorzano. Peace Corps Volunteer archives.

In September of 1969 my time in the Peace Corps was up. I left at a time when the cooperatives were facing serious problems. I left wishing that I had been able to do something to help.

I never went back to visit. Meantime another Peace Corps volunteer who had been with me, Preston Wilson, went back, as many do, and saw some of the changes. He left my email address with the Peace Corps volunteer he met there. That simple act led to a profound change in my life.

One morning in May of 2013 I got an email from Nicolás Pichazaca, one of the children that Lino had pointed to, now in his fifties. He said that the Peace Corps volunteer had been helping his son with English, and Nicolás learned that he had my email address. Immediately, he wrote and asked me to join the work that they were doing, to finish what I had started, he said.

Nicolás Pichazaca with Cañar agave (Photo courtesy Mushuk Yuyay)

He went on to describe what he and the Kañari community were doing. I was stunned! Everything that Lino had dreamed of was being done. Years after Lino had died, his dream was being realized by the next generation. I read what Nicolás wrote, and I could hear Lino speaking. At the time, I was getting ready to retire, but I immediately knew what I would spend my retirement doing.

Pío Alberto Culala, was now in his 80s, barely able to walk and nearly blind, heard that I was still alive and asked the lady in the post office to help him find me. She did. We also got Pío together with Judy Blankenship, a photojournalist putting together the story of the people of Cañar. Judy recorded Pío’s story and helped me Skype with him a couple of times. Thanks to Judy, we have Pío’s story of how the Agrarian Reform led to the people building their cooperatives, taking charge of marketing and finances. Pío Alberto emphasized throughout his narrative that this success was entirely due to the efforts of the Indigenous people themselves. They built on that small and shaky beginning and now have a foundation that is solid and lasting.

Mother and daughter irrigating potatoes in community of Zhuya (Photo courtesy Mushuk Yuyay)

I told Nicolás that I was ready to begin right away. After I got going, Mushuk Yuyay gave me the title of Asesor, making me their official advisor or consultant. I advocate for their work and search for financial and technical assistance everywhere I can. In the six years since I began, I have worked from my home in New Jersey, online, on the telephone, and in person when Kañari community members are in the area visiting or when I can speak to individuals and groups who might be interested in working with us.

They formed a savings and loans cooperative called Mushuk Yuyay. They are their own bankers.

In 1994, they incorporated a non-profit to work on several other agricultural initiatives, also called Mushuk Yuyay: La Asociación de Productores de Semillas y Alimentos Nutricionales Andinos, the association of producers of seeds and nutritious Andean foods. Nicolás Pichazaca is in charge of projects in Mushuk Yuyay, and I work closely with him.

While I was still in the Peace Corps, leaders would argue for hours, sometimes heatedly, about the best way of forming an organization to encompass all of the small individual community cooperatives to work on problems they had in common. I was delighted to learn that it has been done. It is called TUCAYTA. That name is an acronym for All Cañari Cooperatives Together, in Kichwa.

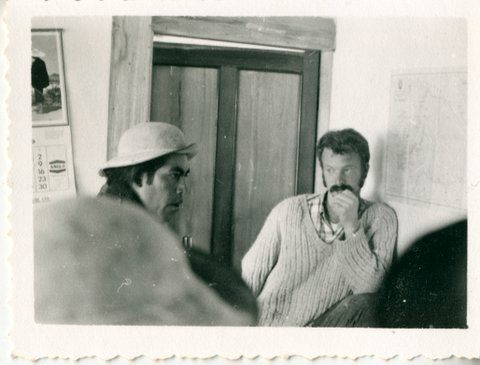

The author in a meeting in 1969 listening to Antonio Quinde (Photo: Peace Corps Volunteers archives)

People were arguing at the time about the value of publishing news in Kichwa, because very few could read it. They barely read Spanish. Now they have universal education in bilingual schools and many of the teachers are the children that I saw playing in the dirt. The Kañari people participate in the national bilingual/bicultural system and use the standardized language, spelled Kichwa.

Alan Adams, third from left, with Kañari colleagues during his Peace Corps stint in 1967-69. (Peace Corps Volunteers archives)

I saw the beginning of the Green Revolution before I left the Peace Corps, and was convinced it would make the minifundio — the small family farm of a few acres, or chakra, as it’s called in Kichwa, productive enough to support the families and forestall the population stress that would lead to emigration. The introduction of agricultural chemicals and mechanized equipment promised a new era of scientific farming, high-yield crops and abundance for all. In reality, the Green Revolution delivered poverty and despair in Cañar as in many parts of the world, causing family farms to fail and be swallowed up by new forms of haciendas.

It began in the late 60s with the Agrarian Reform. The local agronomist performed an experiment that was met with great ceremony. At least he cared to try, and that attention was appreciated. However, quietly, the campesinos confided in me that the plants treated with chemical fertilizers did not fare as well as those given traditional manure. Nobody understood the reasons for that, and outside pressures convinced the Kañari farmers to try more chemicals and the best seeds the world had to offer.

Nicolás, a trained agronomist with wide experience with the National Agricultural Research Institute (INIAP), explained to me that after three years, the local insects and diseases outsmarted the greatest universities of the world and ate their seeds. The amount of biomass in the soil diminished. Erosion sped up. Production took a nosedive. After a few years the Kañari farmers called a halt to the Green Revolution and began to look to their traditional indigenous knowledge that had sustained them for so many generations. Lino wanted Kañari farmers and Kañari technicians to solve the problems of improving production, and that is what is happening.

The author during his Peace Corps service, sitting outside the door. Fellow Peace Corps Volunteer Stuart Moskowitz is on the other side. (Peace Corps Volunteers archives)

In fact, this process of Kañari farmers looking to their more productive past began slowly as soon as the land was back in the hands of the Indigenous farmers. They remembered that production had been higher when the Inca controlled farming, and asked for technical help in reopening the irrigation canals they had built under the direction of the Incas. Over the intervening 400 years, these canals had been washed out in some places. I remember that the surveyors were amazed at the perfection of the Incan engineering. Now, more and more, the younger generation of Kañari professionals are recognizing the value of ancestral wisdom and supplementing it with modern science.

Lino knew that if farming methods were not improved, the people who had been so happy to have their small farms that they had purchased from the Agrarian Reform Institute with so much sacrifice through their newly formed cooperatives, would soon discover that it would be impossible to make a living on them. People would be forced to make a living outside of the Kañari homeland. Emigration was not a new phenomenon for Kañari men, who for years had gone to the coast to earn wages on the large plantations or to carry loads for travelers in bus or train terminals. This gave them some exposure to the outside world, gave them a chance to learn Spanish, but disrupted family and community life.

Restoring the land to acceptable productivity after centuries of abuse under the hacienda system is a slow process. The next meal can’t wait. Besides, there were three other factors that Lino could not foresee that added to the stresses. The Ecuadorian economic crisis of the 2000s wiped out any savings and ruined agricultural markets. The Green Revolution caused sudden crop failures. And climate change turned centuries-old weather patterns into chaos.

People risked the dangers of traveling thousands of miles to the United States and other countries while hiding from police to be able to send cash to their families. The hacienda system had taught them to live with being marginalized. They could live with the deprivations of being on the outside of society in a foreign county. In many cases they were able to send home money, but that did not compensate for the hardship caused by their absence.

But Lino did foresee the resilience, the determination, and the imagination of the Kañari people. He knew that, given the opportunity, they could solve the problems. That is what they are doing through TUCAYTA, the bilingual/bicultural education, the Savings and Loan Cooperative, the community cooperatives, and through Mushuk Yuyay, the association of seed and nutritious food producers.

Typical harvest time scene in Cañar. Archivo Cultural de los Cañaris/Henry Wetsman

Mushuk Yuyay means New Thought, but it is a new way to apply ancestral knowledge and wisdom to a new and changed world. It is an ancient method used to solve problems and confront situations never before seen. The Yuyay that maintained balance for thousands of years can be used to restore balance to Pachamama, the mother that is our Earth. The Western ideas, the thoughts, that caused the problems the people are now facing, are not going to solve them. I read that Einstein said something like that. The Kañari already knew that.

The restoration of balance is an exercise in complexity. Any one change, changes everything. Mushuk Yuyay does not design projects to solve one problem, but to address every aspect of the issues at once. If not, nothing will change. Lino explained that to me. And when, in that morning email in May of 2013, Nicolás showed me what Mushuk Yuyay was doing and planning, I knew that the people understood what needed to be done to make Lino’s dream come true. I could stop wishing that there was a way to make the dream real, and join the effort to do it!

I began my work with Mushuk Yuyay with little preparation. It was obvious immediately that I had to learn a lot about botany, biology, agriculture, economics, and so much more. My five decades as an ESL and bilingual teacher didn’t prepare me to research funders and have long talks with people who were thinking about the problems of poverty and development. I didn’t even know what climate change was. I had to learn about GMOs. Know your enemy. What is quinua? What are the problems with exporting crops? It was like being lost in a large city. You have to learn how to turn around at the end of dead end streets. You have to know how to back out of alleys. You have to read street signs that may or may not be accurate.

Meeting in Newark, September 2016. The author is in the center with wife Paulette to his right. Nicolás is second from the right. Sara Ñusta Pichazaca is in the middle. Her daughters and granddaughter are at the ends. (Photo courtesy Sara Ñusta Pichazaca)

I had to read hundreds of case studies to learn what doesn’t work and who is full of it. I learned that funders favor organizations that feature photos of big gringo bosses who don’t get their hands dirty. I would tell people that we don’t have a big gringo directing this project, but a little old gringo working for the directors. That didn’t work, either.

As Nicolás supplied me with plans, ideas, and budgets and I presented them to foundations, I learned a tremendous amount. At one point I was writing one proposal a week, and my inbox was filling with rejections. It was like fishing, I suppose. Sometimes I got a nibble. Rarely a bite. But, hey, once I reeled in a good one. First Peoples Worldwide helped fund our nutrition education program for a few months. I networked with anyone who would show an interest in helping. I’ve made good friends that way. Returned Peace Corps Volunteers continue to be good collaborators. One suggested the group Friends of Ecuador. I wouldn’t have thought of that. They have been a great help. All donations sent to Mushuk Yuyay through Friends of Ecuador are matched. Terrific! They helped get our nutritionist to the Primer Congreso Mundial del Amaranto in México. They are currently paying for a course that Nicolás will be taking.

Mushuk Yuyay products. Alli Mikuna (Good Food) brand. (Photo courtesy Mushuk Yuyay)

The most fruitful relationship has been with a breeder of quinoa (English translation of the ancient grain that has sustained Andean peoples since time immemorial) at Washington State University. My wife saw a photo in an old National Geographic of a man in a field and said, “Isn’t that quinoa?” I said “Yes.” She said, “You should contact him.” Another shot in the dark. He was developing quinoa for farmers in the Pacific Northwest. Another person making export impossible. It turned out that he had a student from Ecuador and, yes, he would be interested in working with Mushuk Yuyay. Kevin Murphy has been instrumental in developing strains of quinoa for the Cañar communities as well as new varieties of barley adapted for the area. Kevin’s student Leonardo Hinojosa has graduated and is working in Ecuador. He continues to work closely with Mushuk Yuyay.

Try everything. Listen to everybody.

Mushuk Yuyay is organizing women’s farming associations in various communities because emigration has created a labor shortage. The women work together to cultivate and market. These groups address emigration, seed diversity, soil improvement, family nutrition, climate change, resilience, and marketing. My role is to try to find financial and technical assistance to get the groups moving. Their goal is economic self-sufficiency within five years.

Cañari “madrinas” (godmothers) of the Fiesta de Pawkar Raymi hold flowers and guinea pigs, a traditional source of protein for Andean peoples and symbol of abundance. (Archivo Cultural de los Cañaris/Judy Blankenship)

There is an effort to hold soil from erosion, improve nitrogen content, retain water, return carbon to soils, and find new sources of income for the smallholder farmers. This is a three-pronged effort using agave, broom, and bees. I am talking to anyone with ideas about how to make this work and anyone who sees potential problems with it. The agave retains water and soil and produces a sweet juice. The broom fixes nitrogen and holds soil, and has a sweet yellow flower that attracts bees. We need to restore the bee population. They pollinate and make honey. Nobody has just one job.

To address childhood malnutrition, and everything else, Mushuk Yuyay sponsors Healthy Children, Healthy Future (Niños Saludables y Futuro Saludable) in the elementary schools. One of the goals is to produce healthier children who are better students and will make healthy diets a lifelong practice. The program produces amaranth snack bars to sell locally to help support the initiative. Healthy snacks replace junk food. Nutritious local foods replace the national school meals full of food colors and sugar added to GMO soy that contributes to deforesting the Amazon and many other places.

Children participating in Healthy Children, Healthy Future program. (Photo courtesy Mushak Yuyay)

Now, I am talking to nutrition researchers who may help us evaluate the results of the Mushuk Yuyay programs in order to determine how well they work and how they could be improved. This would be participatory research with the community people as well as the Kañari nutritionists and nurses involved.

The community has made great strides during the past 50 years, but they recognize that they have, and will always have, a long way to go. To restore ecosystems, to strengthen agrodiversity, to establish a community solidarity economy, will be an ongoing task, perhaps forever. To create an agriculture that will support food security and a living income will take decades and constant reevaluation and keen innovation. To reverse climate change will take many years of working with millions of people. We’re starting. To create Sumak Kawsay, a beautiful life, wellbeing for all, is a constant effort to seek balance and harmony with Pachamama.

The view in the Cañar highlands is a much greener one today, since the Kañaris have recovered their irrigation system. (Archivo Cultural de los Cañaris/Judy Blankenship)

The Kañari see the world they live in as a tightly unified system that is currently out of balance. One problem affects all of the rest. All issues must be addressed as a whole, and by the united community. Any progress is to be celebrated and evaluated as the people plan for the next step. Sometimes I say that we fit all of the projects together like pieces of a puzzle, but they are pieces that can be fluid. We need to watch, readjust, ask innovative questions, find possible answers. All of the complexities must be nurtured together.

It’s exciting. I love this job! I tell people that retirement is the best job I’ve ever had, but, actually, working with Mushuk Yuyay is the most interesting job I’ve ever had. (And I loved teaching. I retired at age 70.) The possibilities are endless. Every day I read, and search, and talk, and write, and read some more. Since retiring from over forty years of teaching, I have gone through a difficult cancer, but working with Mushuk Yuyay, the projects and the people kept me going, fascinated and hopeful, too involved to give up. We are addressing issues that our lives, the life of the planet, the societies we live in, depend on. Tomorrow will only get better. ¡Esperanza!

[1]Cañar with a “c” is the state nomenclature for the province; Kañari with a “K” is the people. Kichwa lingüistas have replaced the old “c” spelling with c with k: Inka, Kañari, etc. The old “C” spelling is considered the colonial spelling.

An enthusiastic Kañari youth enjoying an amaranth snack. (Photo courtesy Mushuk Yuyay)

Teaser photo credit: Cañari women carry a platform bearing a cornucopia of fruit, flowers and other food in a daylong procession on a fiesta day. (Archivo Cultural de los Cañaris/Judy Blankenship)