Huichol Center’s Susana Valadez: What a long, strange trip it’s been

Susan Eger was more adventurous than your average UCLA anthropology student in 1975 – even for a psychedelic-savvy follower of Carlos Castañeda. But a chance meeting with a fellow adventurer would set her life course in ways she could never have imagined. Nearly half a century later, with three grown indigenous children, a Mexican nonprofit that’s become a living institution and a Nobel nomination to contend with, Susana Valadez, as she is now known, is on fire with the certainty of one who is living her destiny.

With her long mane of curly red hair, her brightly colored traditional Mexican clothing, an easy laugh and her sometimes spicy use of three languages, Susana cuts a larger-than-life figure in the high Western Sierra Madre, and also in the San Francisco Bay area, her base in the U.S. As the founder of the Huichol Center for Cultural Survival and Traditional Arts and a lifelong advocate for their cause, she was chosen by an Amsterdam-based nonprofit, the Drugs Peace Institute, to represent the indigenous Wixárika (Huichol) people, whom the group nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize for “their efforts in favor of a sociable, ecologically friendly and peace-promoting use of mind-altering substances.”

Susana’s dream is to take that Nobel nomination and turn it into long-term institutional support for the Huichol Center, which has served for more than 30 years as a lifeline for thousands of Wixárika families seeking assistance to navigate their way out of desperate poverty and ongoing systemic colonization. And now, as she vies with the likes of Greta Thunberg for the Nobel nomination, she knows her odds are long – but she also knows they are on the same team. “I’d give Greta my vote,” she says.

Susana at home in a hand-embroidered scarf and with a banner her Wixárika friends made to celebrate her return home. “A culture is beautiful but what is lovelier is the one who struggles to keep it alive and perserve it, people like you, Susi.” (Courtesy/Huichol Center)

But Susana has a climate change strategy of her own, and it goes back to the Huichol people and the plant that is their teacher. She has dedicated her life to the cultural survival of these people, and she believes that they and their “sacred medicine plants” hold the key to a breakthrough that could permit humanity to ascend to a higher level of consciousness.

“The only way we will end the war against nature is through a global attitude adjustment, via the use of entheogenic plants,” she maintains. “When people have access to the otherwise inaccessible spiritual realm, under the guidance of practitioners during the ceremonial use of these plants, they enter into an altered state of being where the ‘mind behind nature’ imparts information about the role of humanity as caretakers, stewards of the planet. Once these messages are heeded, individuals experience epiphanies, breakthrough shifts in consciousness that are needed for people to treat nature not as a resource, but as a loving Mother, thus resulting in a paradigm shift.”

A cultural anthropologist following in Castañeda’s footsteps – indeed, her professors had taught the famous author and cultural psychonaut — Valadez had long been intrigued by the hallucinogenic plant traditions found in the Mexican countryside. So naturally when one of her professors introduced her to a man who was living in a remote Huichol village high in the Western Sierra Madre – a backcountry explorer by the name of Peter Collings — and he invited her to come down and check it out, she accepted.

“He talked to me about how there was a desperate need for medicine because so many people were dying from malnutrition, whooping cough, measles and tuberculosis,” she recalls. “So I amassed over a ton of medical supplies, just by going around to nearby Beverly Hills doctors’ offices asking them to clean out their sample drawers. I was able to stockpile a garage full of medicines and lab supplies and dental equipment – but that was my trip: Give me a chore to help solve problems in the world and I’ll do it.”

That’s still her trip, nearly half a century later. At 68, she finds that the chores have just gotten bigger, and she longs for a time when she can sit down and enjoy a stress-free life with her three grandchildren. But for now, she’s showing no signs of slowing down. She’s built a solid hub for the sprawling Wixárika communities, who inhabit a territory larger than the Mexican state of Colima. There she’s built a community in the mountain town of Huejuquilla el Alto, Jalisco, to support a multifaceted organization to thwart cultural extinction that includes an indigenous school, various projects to promote economic self-sufficiency, a sustainable agriculture program, a vast ethnographic archive, a Wixárika art gallery, and an ongoing fund to assist and provide relief to families and individuals in crisis.

Susana’s daughter Rosy making a traditional yarn painting, embedded with the key symbols of the Wixarika cosmology (Courtesy/Huichol Center)

The Huichol Center works with local health care practitioners as well as traditional shamans to provide medical assistance where there is limited access. Widows and domestic violence victims are taken under the wing of the Huichol Center and taught how to fend for themselves by learning marketable skills to support their families. And the Huichol School teaches children to navigate the modern world while uplifting and validating the Wixárika culture, rather than erasing it, as the dominant society and government schools tend to do.

It’s taken years of painstaking work to get to this point, generating operational funds for the Huichol Center by selling the art and jewelry created there, and Susana worries that it could all disappear if she’s not able to find more ongoing sources of support. And she is also concerned that she won’t have time to properly archive and interpret the decades of ethnographic research she’s collected on the fly. Sometimes she jokes about winning the lottery; most of the time she prays for miracles, which she relies upon as her “modus operandi”. Now, with the Nobel nomination in play, she hopes to rise to another level in the global playing field.

“If we set our intentions right, we can raise the consciousness of humanity at large, about the magnificent contributions that indigenous people have gifted to the world for all these centuries. I personally feel the deepest sense of remorse about how much was stolen from First Nations peoples, both physically and spiritually, and how badly they’ve been abused by the greater part of the human population under the guise of colonialism,” she said. “They were the weaker ones because they were – and are – involved in tending to spiritual matters, and not so much matters of the physical world.

“And what the Nobel nomination can give back to them is a real voice in the global arena, about how decisions are made regarding their sacred visionary plants, to give voice to the people and to their plants, by giving them the recognition, and mas que nada, the veneration that is their due, to restore the equilibrium between First Nation peoples, their connection to nature and the world at large – the invaders.

“We need to come to a conclusion about that – that’s never been concluded or resolved. All the treaties have been broken — you went to Standing Rock, right? How can that still be happening to Native people in the modern age?”

Students from the Huichol School practice a traditional song. Unlike most Mexican public schools, the Huichol School works to honor the Wixárika culture and keep the traditions alive. (Courtesy/Huichol Center)

Standing at a Crossroads

The Wixárika territory that Susana arrived in that summer of 1975 was beyond imagining. She and her precious cargo of medical supplies were flown in with a big World War II army plane. The vista that opened up to her was breathtaking: A vast, Grand Canyon-like landscape, covered in pine forests and dotted with tiny settlements.

She was entranced by what she found: A people with a complex ancient cosmovision fueled by an entheogenic connection to the ancestors, the elements and the forces of life on the planet — about to be crushed by the steamroller of Western civilization.

“Back then, ceremonial dress was everyday dress. And there was so much embroidery – San Andres women fully embroidered up – maybe they’d be in ceremonial dress or sometimes just a skirt that they’d wear around the ranch would have two or three lines of embroidery,” she said. Having studied the symbols that Norwegian ethnographer Carl Lumholtz recorded a century earlier, she recognized them. “Oh my God, this scene is taken right out of Lumholtz’s time,” she thought.

“The moment I got there I realized I had stumbled upon a treasure trove of indigenous knowledge, the real Treasure of the Sierra Madres” she said. “I found a diamond in the rough in the Huichol community, because I realized that they themselves didn’t know the importance of what they were holding onto and hopefully safeguarding for future generations.”

Wixárika members of the San Andrés community of La Laguna prepare to descend into the canyon to perform a corn ritual. (Tracy L. Barnett photo)

Susana arrived in the village of San Andrés Cohamiata at a point in time when the first road was being completed into their remote homeland. She brought three planeloads of medicines to deliver to the village nurse, Rocio Echevarria, who invited her to stay for a while; besides her fascination with the people and their culture, a romance was developing between her and her guide, Peter.

“I was standing at a crossroads in my life at the same time the Huichols were standing at a crossroads for their future,” she said. “They really had no idea what was about to hit them — nor did I.”

The first few months when she was just getting acclimated, she began to notice that there were far too many deaths occurring in the village. “Our house was on the path to the graveyard, and people passed by carrying coffins a LOT,” she recalled. “Huichols leaving their communities and returning to the isolated homeland where their immune systems were unable to fend off these newly introduced epidemics. So that became apparent. Lots of malnutrition, lots of babies so malnourished and sick that I could hardy bear to look at them because of the flies crawling in their eyes and around their mouths. Brutally bad poverty.”

Susana, right, in San Andrés Cohamiata in 1975 (Courtesy/Huichol Center)

She began a collaboration with Rocio Echevarría, the nurse who later went on to found the Casa Wixárika, another regional institution in Guadalajara dedicated to combating disease among the Wixárika population and assisting them through the sometimes byzantine Mexican public health process.

Her relationship with Collings didn’t last. But it brought her face-to-face with her destiny and then with the man who would be the father of her children: Mariano Valadez, a traditional artist who specialized in yarn painting, from Santa Catarina Cuexcomatitlán. Thus began a whole new chapter of her life.

Mariano practiced a high form of art that was derived from the votive art the Huichols created as offerings to spiritual beings to venerate their creators and celebrate their human existence. Shamans with their magical feathered wands would spring from his canvas, along with deer and wolf and eagle spirits, elements of wind and fire and water, and at the center of it all, the deeply sacred peyote cactus, emanating waves of energy and colors that pulsed with light.

Traditional yarn painting by Mariano Valadez (Courtesy/Huichol Center)

“He was extremely talented – but also extremely poor,” she said. The young married couple migrated to Santiago Ixcuintla, in the neighboring state of Nayarit, a gritty tobacco town where his family, like so many other impoverished Wixárika families, including pregnant women, infants and children had seasonally migrated to for years to work in the tobacco fields. The work was grinding and dangerous – constant exposure to toxic pesticides led to scandalous levels of cancer and other more immediate ailments, leading to the groundbreaking documentary by Patricia Díaz Romo, Huicholes y Plaguicidas (Huichols and Pesticides).

That’s where Susana established the first Huichol Center, doing what she could to help with the profound levels of need that she saw all around her. There was no money – she had been on scholarship at UCLA, and her family was not well-off. So she began making trips to California to sell the colorful beaded jewelry and yarn paintings that her new husband and family of friends were making. She and Mariano went to LA for months at a time, where they started a lawn care business (“He was the mower, I was the driver”) and she began what would be a lifelong mission to raise money to improve the quality of life for the impossibly poor Wixárika people.

But her goal was to awaken the Huichols to how to use their cultural heritage as an asset, by “transforming field hands into creative hands,” as her early campaigns put it. Eventually she opened a gallery in the bohemian seaside village of Sayulita, Nayarit, where she was able to funnel a stream of tourist dollars into her charitable organization. In the process, they raised their three children – son Cilau, an accomplished and high-profile artist in his own right; Rosy, now a schoolteacher; and Angélica, a Huichol jewelry designer and Huichol Center representative.

Susana and Mariano in the sierras with their growing family (Courtesy/Huichol Center)

In 1994 the Huichol Center moved from Santiago in Nayarit back up to the Sierra of Northern Jalisco, to the town of Huejuquilla, to be closer to the Wixárika communities. There she resides on a 12-acre ranch and permaculture center, dividing her time between overseeing the farm and the Huichol Center School, organizing permaculture and biodynamic farming trainings and jewelry-making workshops for the Wixarika people in the town, while also working on the ethnographic archives and dreaming up new ideas to keep the Huichol Center alive and thriving into the next generations.

Right now she’s getting ready to launch a new project that she hopes will bring in a steady stream of revenue for the Center: “Ethno-Graphics,” a website where people can download line drawings of the ancient art and symbols and use it to make their own sacred art and designs.

“I think that’s one of the best innovations I’ve ever had,” she said. She worked for years with shaman friends and artists to document thousands of images, later transformed into line drawings, and hit upon the idea as a way to generate income in a low-carbon way, instead of traveling all over selling the art.

“We already have all these educational materials and line drawings that we use in our school to teach the Huichol children about their symbols and traditions. And the most exciting thing about that is that the descriptions of each drawing can be translated on our website into many languages, making these beautiful drawings and explanations available to a global marketplace. We’re thinking of putting up something like one of these line drawings every day for people to download and print, then to color or use for inspiration.” she said, opening her notebook excitedly to show a sample of a peyote mandala radiating life force to the people attending a ceremony.

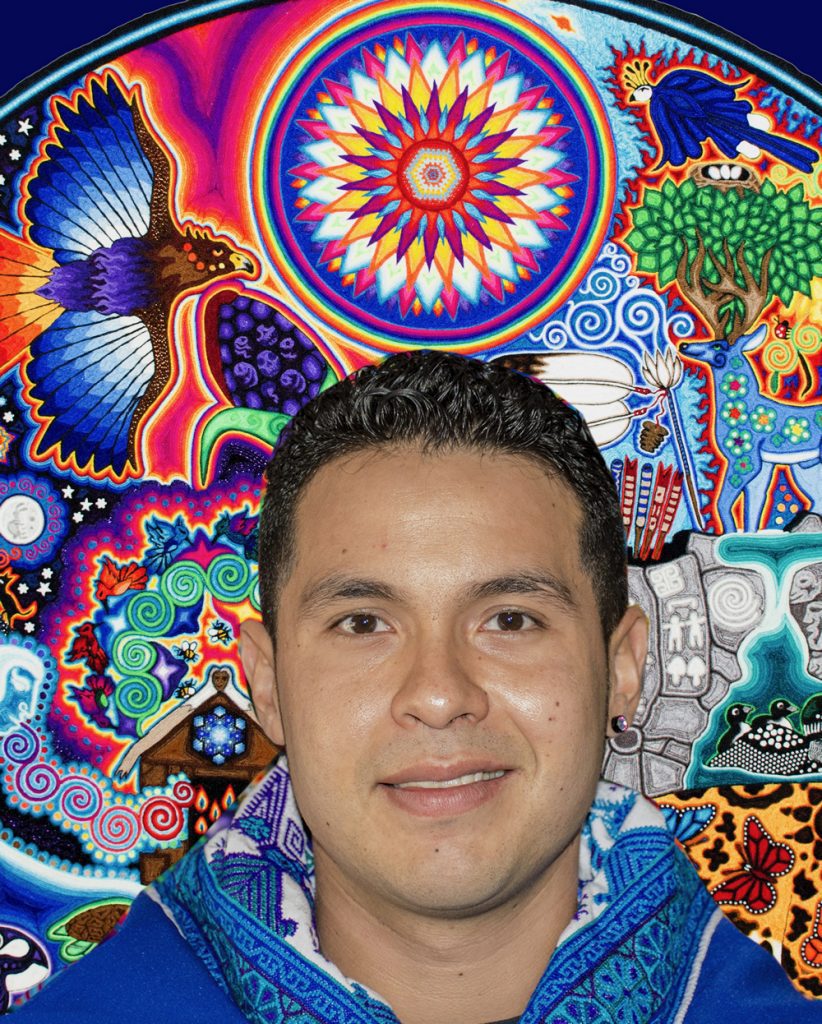

Cilau Valadez, Susana and Mariano’s son, is now an internationally recognized contemporary yarn painter with a studio and gallery in Sayulita, Nayarit. (Courtesy/Huichol Center)

Ethno-graphics is just one of her many ideas to ensure the continuation of this endangered population, from a mind that is brimming with them. A benefit of her alliance with the sacred plant medicines, perhaps. And she knows it’s a long shot that she’ll nail the Nobel Peace Prize, but she’s been working the nomination non-stop to bring benefits to the Wixárika people, and doesn’t plan to quit, no matter who wins the honors.

“You know, whether or not it happens, I’m going to keep going, because I really believe that my whole destiny has led me up to this point,” she said. “It’s like having seeds that you’ve been incubating for all these years, and now it’s time to plant them into the fertile soils of our times, when our planet is in peril. We’ve been making the soil ready for these new ideas and seeds of consciousness.

“I look forward to the day when the sacred plants will be decriminalized, so that people will be able to explore Nature’s hidden mysteries, and learn the ethics of Earth care. I have faith that indigenous wisdom will play a huge part in the future of humanity. And if we win, we win; and if we don’t, we don’t – but I love my life’s work, and I’m having a great time.”

Susana with children at the Huichol School (Courtesy/Huichol Center)

Next: Susana on the “sacred plants” as medicine, as a human right and as a teacher and guide to other dimensions of knowledge — teachings we badly need in these perilous times.

To support the Huichol Center, follow them on Facebook; browse their extensive website; make a tax-deductible donation here, and/or help steer them towards individuals or organizations that may help them procure long-term institutional support. They are also seeking collaborations that will further their goals: to provide humanitarian aid while implementing many long term, successful strategies to raise the quality of their lives and safeguard their ancient ways. These programs include Huichol language education at the Huichol School, skill training that fosters economic self-sufficiency through the production of native arts, support for the guardians of the peyote traditions and the elimination of hunger by teaching eco-technologies to insure food and water security.

Susana with daughter Angélica, Huichol designer and Huichol Center spokesperson, at the Huichol School (Courtesy/Huichol Center)