Sometimes a headline gives you practically the entire story. Take this one: “Gene-Editing Unintentionally Adds Bovine DNA, Goat DNA, and Bacterial DNA, Mouse Researchers Find.” The writer details how this happens, of course. And, there is an important subtext. The problem is chalked up by scientists and regulators to incompetence on the part of the company doing alterations to create cattle without horns.

But the real news is this according the author: “[F]oreign DNA from surprising sources can routinely find its way into the genome of edited animals. This genetic material is not DNA that was put there on purpose, but rather, is a contaminant of standard editing procedures.” [My emphasis.]

At the risk of sounding like a broken record (remember records?), as Garrett Hardin, the author of the first law of ecology, reminds us, “we can never merely do one thing.” Why is this truism so hard to accept, so hard that I feel compelled to refer to it in consecutive posts? The simple answer is that as long as there is profit in ignoring it and as long as it is possible to pass the bad consequences on to others, people will act as if Hardin’s first law was never spoken.

Unfortunately, we ignore Hardin in practically everything we do. For example, we discover the convenience of tough, clear plastics and create health damage with the chemical that makes them that way. We later discover that plastic degrades into very tiny particles that are now ubiquitous on the planet and in our bodies as well.

In each case the damage is spread around as the profits mount for the makers. But even they can no longer escape their handiwork. The damage now makes its way into the corporate suites and penthouses.

Any thinking person can understand the system we now have. Each company and its employees, even if they know they are degrading the environment and undermining the health of their customers with their products, focus on doing these anyway believing that somehow they can “get away with it.” But when contaminated food, dangerous products and environmental damage are generated by competitors and practically every other business on the planet, no one can escape.

So, is there any possible escape from such a system? Must it first collapse before anything new can take its place? I believe the answer to the first question is “yes” and the second “no”—though collapse may be the most likely trajectory.

Already there are many, many people who reject genetically engineered foods; who are growing clean foods in ways that improve the soil; spreading natural therapies for better health and vitality; rebuilding links to their neighbors and fellow citizens; and doing their best to abstain from acts that speed up the mess.

Are these efforts enough to avert a collapse? The answer is that these efforts are not directed at stopping a collapse of our current system. Rather, they are directed at building the new forms of living that will replace the current system as it collapses. Whether that collapse is piecemeal or involves a horrible and dramatic climax, no one can say for certain. But it should be clear that the current system is changing and being slowly replaced by new forms that better attend to our health and happiness—even if society must first go through the terrible throes of loss as the existing system crumbles.

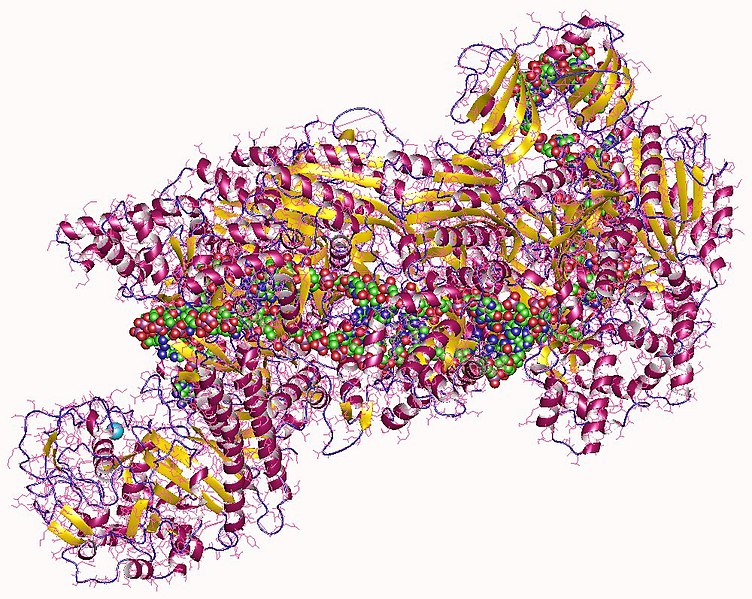

Image: CRISPR (= Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) + DNA fragment, E.Coli. From RCSP Protein Data Bank (2014). Via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:4qyz.jpg