Any plan for the future is a gamble. We cannot know what the future holds, we can only make a reasoned guess based on the evidence we have available.

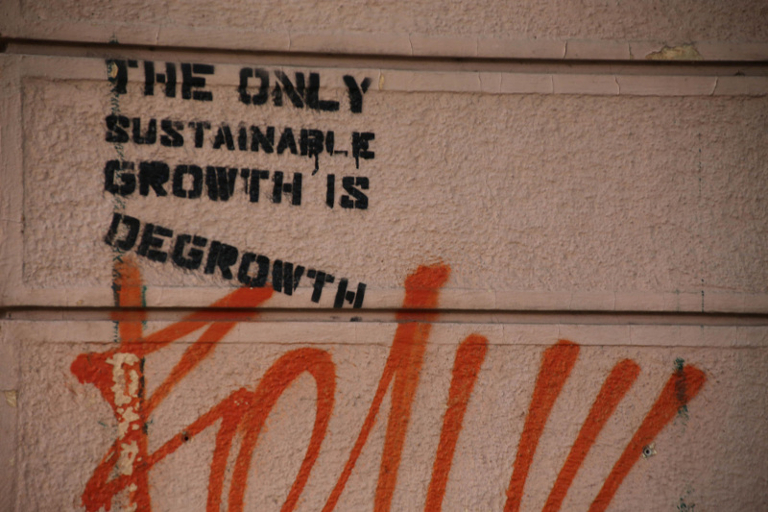

But not all gambling is the same. Different bets have different odds, and different stakes. Sustainable growth is a bad bet, the stakes are high, the odds low and the payout low. On the other hand, degrowth is a good bet: its stakes are low, odds high and the payout high.

Clearly this view is very different than the one Leigh Phillips set up in his recent essay ‘The Degrowth Delusion’. Here, Leigh attacks what he sees as a revival of Malthusian thinking in ‘sections of the environmental community’, which have embraced ‘limits to growth’ arguments.

He lumps together several thinkers whose views are by no means identical, and accuses them of abandoning progress. Leigh’s main contentions are these:

1) The continuation of economic growth is necessary for continued human progress.

2) To reject the ideology and established forms of economic growth is to embrace ‘Malthusianism’ and ‘eco-Thatcherism’.

3) We have clear evidence that the industrial capitalist economy can incrementally absolutely decouple economic growth from damaging ecological externalities.

4) The best way to achieve sustainable green growth is to establish central socialist planning which will deliver an eco-friendly high-technology economy.

5) There are in effect no limits on economic growth, and thus we can have the boundless technological progress on which he believes our wellbeing depends.

He is wrong on all these points. He is making a bad bet.

Can we have absolute decoupling to enable endless growth?

The core problem with the sustainable growth bet is that there is very little evidence that it can be achieved in a timeframe that will enable us to avoid catastrophic climate change. Sustainable growth requires us to ‘decouple’ environmental impact from economic activity. That is, we have to work out a way to produce more stuff while producing less carbon dioxide. For the last 300 years, we have only been able to produce more stuff by producing more carbon dioxide.

Leigh argues that this is because we have failed to use the right policies to control and eliminate negative externalities such as pollution and dangerous climate disruption. In recent decades we have fixated on market-based solutions to the problem of reducing carbon emissions or other harms. These cannot do the job properly. What can do it, argues Leigh, is determined state-led regulation and standard-setting. Leigh’s prime example here is the rescue of the ozone layer from degradation by CFC gases, thanks to regulation by governments the industries concerned. Given enough determination by state actors, we can regulate our way to sustainable growth and achieve, as in the case of elimination of ozone-depleting chemicals, an absolute decoupling of economic growth from a harmful externality. In other words the problem is not growth, it is neoliberalism.

Neoliberal economics is fundamentally at odds with radical decarbonisation. State regulation does have a crucially important role to play in giving ‘long, loud and legal’ signals and incentives to enterprises to make changes in design and production. None of this changes the challenge of growth. Whether socialist or neoliberal, growth requires ‘absolute decoupling’: achieving economic growth while reducing and removing the inputs and impacts it has previously relied on.

Absolute decoupling is tough. There are many examples of relative decoupling of growth from damaging side-effects and inputs, as technologies become more energy-efficient, for example. But relative decoupling is nothing like enough to deal with the challenges posed by climate disruption. Efficiency gains at the margin are swamped by increases in consumption that generate more emissions. Relative decoupling only means that things like carbon emissions go up less fast. We need them to go down. So we need absolute decoupling, above all of economic growth from fossil fuel emissions. Everything hinges on achieving it across the board in the space of a few decades, and in the case of greenhouse emissions much sooner in the wealthy countries.

Leigh relies heavily on the case of ozone-depleting chemicals to show that this is feasible. But to ensure sustainable growth on his terms, given that he accepts the urgency and necessity of breaches in planetary boundaries such as the onset of climate disruption, he needs absolute decoupling to take place across many sectors and especially in the link between economic growth and greenhouse gas emissions. Decoupling CFCs from economic growth is trivial by comparison with the task of decoupling growth from the entire fossil energy base that has made it possible at all.

According to Leigh: “The only question that remains is whether absolute decoupling can be extended across all sectors, or sufficient sectors as to eliminate undermining of ecosystem services.” It cannot.

There are very few examples of absolute decoupling. Consider the conclusions of a comprehensive recent review of the evidence by the NGO research network EEB:

“…not only is there no empirical evidence supporting the existence of a decoupling of economic growth from environmental pressures on anywhere near the scale needed to deal with environmental breakdown, but also, and perhaps more importantly, such decoupling appears unlikely to happen in the future.”

The EEB team note that this is no reason to abandon efforts to achieve absolute decoupling of economic development from environmental bads. But it does give reason to “have major concerns about the predominant focus of policymakers on green growth, this focus being based on the flawed assumption that sufficient decoupling can be achieved through increased efficiency without limiting economic production and consumption”.

As the climate crisis unfolds around us, can we seriously rely on faith in rescue via absolute decoupling of growth from greenhouse gas emissions through unproven new technologies?

Even if we assume that we can have such faith in technological innovations to generate absolute decoupling, we also have to ask whether they can arrive in time. We need to limit global heating to 1.5 degrees in the next few decades. The world’s economies currently emit some 37 billion tonnes of carbon per annum, and that number is still growing. If emissions continue at this rate, the carbon budget will be used up in less than 20 years.

The rate of decarbonisation that’s needed is huge, all the more so if we in the wealthy countries allow, as we should, for gains in consumption and production in poor countries. Continuing economic growth as we know it makes this enormous challenge even tougher. The deadline for achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions is close: Tim Jackson’s recent report ‘Zero Carbon Sooner’, suggests that “reduction rates high enough both to lead to zero carbon (on a consumption basis) by 2050 and to remain within the carbon budget require absolute reductions of more than 95% of carbon emissions as early as 2030.”

Reliance on absolute decoupling via new technologies cannot be justified except as an act of faith. Technological innovation for emissions reduction is a vital part of transition to a sustainable economy. It is a key ingredient in proposals for ‘Green New Deals’. But it is far from clear that new technologies will be developed in time, if at all (e.g. nuclear fusion); or that they will be safe and governable (e.g. large-scale geo-engineering); or effective (e.g. so-called negative emission technologies).

It is also arguably the case that the rate of significant innovation overall is slowing. Development of new technologies of these kinds also requires large-scale inputs of investment, materials and energy, all representing a huge opportunity cost and diversion of resources.

There are also two fundamental ecological factors to contend with. First, as argued by the ecological economists Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen and Herman Daly, thermodynamics sets inescapable constraints on economic growth and the use of non-renewable resources, and generates inevitable costs in capturing value from resources, even the free solar energy falling on to the Earth. There are no free lunches. All economic activity requires energy and materials. Infinite growth on a finite planet cannot happen.

Second, our economies are dependent on an immense, intricate and poorly understood web of bio-geophysical systems, from the oceans to the upper atmosphere, that set what have been described as ‘planetary boundaries’, tolerances for Earth system functioning that we adjust, disrupt or ignore at our peril. Breaching the boundaries – in particular disrupting the carbon cycle and forcing global heating as we have done – is a civilisational risk. The onset of severe disruption in planetary life-support services is very likely to undermine societies such that economic growth will not continue in any case. The other is that the reason the disruption is happening or in prospect is because of the scale and impacts of the economic growth that we have had.

We are thus in a ‘growth trap’. The only way out of this dilemma and secure further growth, is either to find a spare planet to mine and pollute, or to achieve absolute decoupling via new technologies. Spare planets or asteroids will not come to our aid in any timescale that will allow us to avoid climate crisis. And, as we have seen, there is little evidence to support the idea of absolute decoupling via technology.

For all these reasons, aiming for ‘sustainable growth’ in the form of an absolutely decoupled version of industrial growth as we have known is a bad bet with long odds which puts the livelihoods of billions of people at stake. We therefore have to confront the challenge of another kind of absolute decoupling, that of prosperity and wellbeing from growth in material extraction, production and consumption. What can that mean?

What we mean when we talk about ‘degrowth’

Degrowth is a contested idea. However, it is not the same as recession (negative GDP growth) and imposed austerity, as are experienced when the capitalist growth machine stalls. Because ‘degrowth’ can evoke misleading images of decay and regression, some thinkers and advocates for a radical reimagining and reshaping of the economic system speak instead of ‘post-growth’ models. Yes there needs to be radical reduction in demand for forms of consumption and production that cannot be sustained ecologically. But this must come from a reorientation of economic purpose from away from maximisation of market value.

Degrowth and post-growth advocates contend that we need to focus on the ends of human wellbeing and ecological health. Economic tools and policies are a means to those ends. The growth economy as we know it is fixated on growth as an end, not just as a means. Its defenders, like Leigh Phillips, fail to ask the fundamental questions posed by degrowth and post-growth advocates. When we speak of economic growth in a world of limits, we have to ask always, growth of what, where, for whom, with what impacts, and for how long?

There is no reason to see boundless economic growth, even if it could be achieved, as essential to progress in wellbeing. The evidence is clear that beyond a certain level of income, diminishing returns set in for wellbeing as growth goes up. This especially true for the poor and has even been true for large sections of middle classes worldwide over the past three to four decades. The gains from growth have been skewed to the rich, and remain so. And there are other ways in which growth fails to benefit the worse-off, and to undermine wellbeing for all. As environmental problems mount up, and as social divisions and public services worsen for many, so an increasing proportion of GDP growth is taken up by ‘defensive spending’ on problems generated by the economic machine and its political priorities.

Post-growth visions of the economy are founded on profound reorientation of economic policy and social priorities. Post-growth and degrowth advocates are intensely concerned with injustice and inequalities and with ensuring fair transitions and redistribution within a reformed economy, as is clear from the literature. The goal is to enable and enhance wellbeing.

To grow our collective wellbeing, some parts of the economy need to contract and some need to expand. For example, we need radical reduction, indeed probably the elimination, of fossil fuel inputs. But this is coupled to need for a great expansion in renewable energy systems. It is also plain that up to a point economic growth is correlated with material progress and gains in wellbeing for the poor. We in the rich global North need to allow the ecological ‘space’ or ‘headroom’ for substantial economic growth in much of the global South, on grounds of social justice and equity. That means a programme of demand reduction, redistribution and reorientation of social goals in the rich world to enable this.

In a post-growth economy, innovation will continue. But it will be a different kind of innovation. Instead of innovation that aims to deliver yet another new iPhone, we need social and institutional innovation that enables us to live better, happier lives. Post-growth economies and societies will not be static; they will be developing still, but within planetary limits, and they will not be betting their futures on the assumption of endless material growth that can always achieve absolute decoupling from bad side-effects.

In other words, the potential winnings from the degrowth bet is a society focused on providing things that make life worth living, beyond new consumer goods. More time with your family, more creative work, a more equitable distribution of income. And it aims to provide these without undermining the ecological systems that enable us to live in the first place. None of this means abandonment of technological innovation or of wellbeing. Rather, it means focusing on more meaningful types of innovation and wellbeing than can be provided by the expansion of consumer goods alone.

Prosperity without growth, or growth with socialist planning?

Post- and de-growthers are concerned to bring about a democratic, cooperative and equitable shift – a Just Transition – to a humane, convivial and ecologically healthy economic system. What we don’t yet have is a comprehensive programme for doing this – hence the rich diversity and debate among de- and post-growth advocates and with proponents of ‘green’ or ‘sustainable’ growth. As Katherine Trebeck and Jeremy Williams point out in their book ‘The Economics of Arrival’:

“…post-growth economics is not a fully fleshed-out system waiting in the wings for some big future switchover. Nor are our own notions of Arrival and making ourselves at home. Moving towards these alternatives will be an evolutionary process, driven partly by new ideas and partly by the failure of old ones… The alternatives will be something that people and communities discover together.”

One perspective argues for a pragmatic and mixed-economy approach to the shift to post-growth. It will require experimentation at all levels and across sectors. It will call for state regulation and also new forms of bottom-up grassroots social enterprise; it will demand high technology and social innovations; it will be multi-level and ‘polycentric’; it will involve coalitions of the willing between capitalist big business and sustainability NGOs; it will be messy and improvisational as well as based on state-led steering and foresight. It will not be ‘neoliberal’ in spirit or policy, and it will have more to do with new forms of regulation and decentralised planning and innovation than was the case in postwar state-directed economic planning.

By contrast, Leigh Phillips argues that the way ahead is centralised state socialist planning. He doesn’t tell us what the political and cultural path is from here to this regime for the management of boundless growth and sustainable abundance. At the least, we might question whether the history of central planning, whether in nominally state socialist societies or in the social democratic states of the postwar West, gives confidence in policymakers’ ability to direct economies through the immensely complex transitions that lie ahead for the next two generations. In both cases, economic growth was accompanied by, and gave rise to, immense ecological damage and consequent harms to health and quality of life.

Degrowth vs sustainable growth: a hopeful gamble vs a fools bet

To recap:

1) Human knowledge, technology, freedom and prosperity can continue to develop in the absence of economic growth.

2) Moving beyond economic growth does not necessarily involve a mindset and strategy of austerity.

3) The balance of evidence suggests that economy-wide absolute decoupling of GHG emissions and harms from growth within the required timescale is highly unrealistic.

4) There is still immense work to be done in deciding how to organise our economies to deliver sustainable prosperity for all.

5) We have to take the physical and ecological limits of our planet as the starting point.

Sustainable growth is a bad bet. The odds of success are bad. For sustainable growth we have to escape the limits of the Earth or decouple absolutely from negative externalities. We have no evidence that this can be done, certainly not in time to mitigate dangerous climate disruption. Climate disruption will end growth. The claim and insistence that absolute decoupling can be done are little more than a quasi-religious belief in economic growth as the fundamental precondition of hope in a secularised immanent worldview. The payout of the sustainable growth bet is also low. Sustainable growth offers us more of the same. More stuff, not more meaning or control.

‘Degrowth’ is a good bet. There is sound empirical and theoretical evidence that our economies are dependent on material and energy resources and embedded in the delicate balance of the Earth’s life systems. And if we pull it off, the payout is huge. Not more of the same, but a radically reimagined economy that prioritises the good life over growth. Yes, less stuff. But in return – more community, more nature, and more say over how we live our lives.

Further reading

Centre for Understanding Sustainable Prosperity, www.cusp.ac.uk

D’Alisa, G. et al, eds. (2015), Degrowth: a vocabulary for a new era, Routledge: Abingdon

Gordon, R. (2016), The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living since the Civil War, Princeton University Press: Princeton

Jackson, T. (2017), Prosperity without Growth, second edition, Routledge: Abingdon

Jackson, T. and Webster, R. (2016), Limits Revisited, APPG Limits to Growth/University of Surrey: http://limits2growth.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Jackson-and-Webster-2016-Limits-Revisited.pdf

McNeill, J. and Engelke, P. (2014), The Great Acceleration: an environmental history of the Anthropocene since 1945, Belknap Press: Cambridge, MA.

O’Neill, D. et al (2018), ‘A good life for all within planetary boundaries’, Nature Sustainability, vol.1, 88-95, February: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-018-0021-4

Raworth, K. (2017), Doughnut Economics, Penguin: London

Steffen, W. et al (2015), ‘Planetary boundaries: guiding human development on a changing planet’, Science 1259855.

Trebeck, K. and Williams, J. (2019), The Economics of Arrival, Policy Press: Bristol

Victor, P. (2019), Managing without Growth, second edition, Edward Elgar: Cheltenham