Onondaga Nation, New York – Angela Ferguson opens a door unveiling thousands of jars filled with corn seeds from across Turtle Island. The color and the sheer number of seed varieties washing over the room is overwhelming in and of itself, but it is what these seeds represent that is truly inspiring. Angela Ferguson is a Traditional Corn Grower from the Onondaga Nation and one of the founders of Braiding The Sacred, a growing network of indigenous corn keepers that help Indigenous Nations across Turtle Island recover and reunite with their communities sacred seeds and traditional food sources.

Years ago, Ferguson was given a seed bank that consisted of thousands of varieties of heritage corn seeds from across Turtle Island. The seed bank was initially managed by Carl “White Eagle” Barnes. When Barnes passed away, he bestowed the collection to his apprentice who in turn gave it to Ferguson.

When Ferguson first saw the collection, “I cried, just looking at all these seeds in these big giant tubs, thinking how many people have traveled, been displaced, took those seeds with them on their journeys, and grown them throughout millennia.” When the collection made its way to the Onondaga Nation, Ferguson and members of the Onondaga Nation sorted it, had ceremony for it, burnt tobacco, and diligently cleaned it up with help from volunteers. So far, they have sorted and identified 1,167 of the more than 2,000 varieties in the collection.

Angela Ferguson, a leader in the Onondaga Nation Farm Crew and Braiding the Sacred displaying some of the corn varieties they are reviving and propagating to feed to the people. Photo: Garet Bleir

“It’s overwhelming because some of these seeds have no more people,” Ferguson told IC. “All their people are extinct, wiped out, or absorbed into other tribes. But the food lived on.” Some varieties of the corn lining the shelves are the last of their kind on Earth. Now Ferguson and others at the farm crew are responsible for growing the seeds out and getting them back to their own people. Or, if there are willing planters in those nations, Ferguson makes sure they can propagate the seeds themselves. Ferguson is currently working with approximately 100 different planters across the U.S. In addition to the corn varieties, she is also working with over 500 varieties of beans.

This work has not only protected thousands of varieties of heirloom corn for future generations but also has inspired seed keepers across Turtle Island. Douglas “Jack” DesJarlait of Red Lake Nation, Minnesota, attended a food sovereignty gathering last year that Ferguson and other representatives of Braiding the Sacred happened to be attending. After learning more about Braiding the Sacred, he gifted Ferguson a jar of corn seeds; a variety of which he was the last grower. Ferguson recalls him telling her, “The corn that I’m going to give to you came with our Ojibwe people. Our medicine people told us to migrate West from the mouth of the St. Lawrence Seaway to this location, and we brought those seeds with us. I think the reason that I met you guys is that the seeds want to go back home. You all are from there, and I want you to take the corn back.”

When Ferguson returned home, she propagated the seed on the Onondaga Nation. After harvesting the corn, she then took the seed to the Mohawk community of Akwesasne so they can grow the seed and send it on to the Kahnawake Mohawks, who will in turn send it up to a third Mohawk community, Kanesatake, where the seed originated. “It’s making its journey, and in the meantime all these connections are being made between communities,” says Ferguson. After hearing of this story, Ferguson and members of the Mohawk Nations invited DesJarlait to come East to tell his story to the new growers of these seeds.

Before this, DesJarlait had almost quit growing the seeds forever. Ferguson recalls him saying, “I used to wonder, why do I grow this? Nobody cares about it anymore. Everyone makes fun of me. They think I’m just a poor little farmer and no one thinks any value of it. Until I met you, I was going to quit planting this very same year.” With newfound purpose and inspiration, DesJarlait decided to continue planting his seeds for future generations.

On the Onondaga Nation, Ferguson has shown how these heirloom seeds have the power to not only bring together indigenous nations but also individuals within their own communities.

Cherokee Glass Gem Corn. Photo: Garet Bleir

ANCESTRAL DIET AND FARMING PRACTICES OF THE ONONDAGA NATION

The present-day Onondaga Nation extends over 7,000 acres of land south of Syracuse, New York in its ancestral territory. A member nation of the Six Nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy–more commonly known by its French-given name, the Iroquois Confederacy–the Onondaga traditionally resided on the hilltops surrounding the Finger Lakes region of present-day New York. When it came time for summer planting, people came down to the cornfields and gardens of the flatlands set up adjacent to their spring and summer fishing villages. Varieties of corn, beans, and squash, known as the Three Sisters, served as the basis of the Onondaga diet. The transition into Fall and Winter signaled a time for hunting deer, turkey, rabbit, and other game found throughout the area.

In order to ensure the community has enough to prosper, hunters and planters alike are taught to take only what is needed. “It was the duty of the people that grew those communal gardens to provide enough for all of the ceremonies, to plant for the elderly or sick people who were not able to do that, and to share the abundance at the end,” says Ferguson, who also serves as a leader of the Onondaga Nation Farm Crew. Anything that was left over was equally divvied up amongst everyone in the community.

Today, the Onondaga Nation Farm Crew works to continue and reconnect members of the Onondaga Nation with their ancestors’ traditional methods of agriculture, hunting, fishing, food gathering, and preparation. The farm currently employs fifteen women who handle the traditional agriculture, foraging, cooking methods, and beekeeping; as well as five men who handle the hunting, fishing, and foraging. As many as ten youth are also mentored during the summer season.

Onondaga Nation Farm Crew Beehives. Photo: Angela Ferguson

When the Onondaga Nation Farm Crew first started its work nearly eight years ago, Ferguson and several others prioritized their efforts to deliver foods to elders in the community. This gave them an opportunity to form new relationships and share traditional recipes with the elders, as well as a chance to learn the history of the Onondaga Nation from them.

After five years of working like this, Ferguson decided that she wanted to serve the whole community. In 2015, through Onondaga Nation Council approval and funding, Ferguson was able to expand the operation, moving from individual visits to community gatherings in a central location. Vegetables, meat, salmon and other foods are laid out and presented to the community, all for free. Other members in the community were so inspired by these gatherings that they started giving out their own vegetables from their garden.“It’s not just the food that’s the medicine, it’s also the coming together, the exchange, the laughter, the conversation, good energy, and then the food at the end is the gift,” says Ferguson. “And that is the component that is going to draw communities back together; it’s the food.”

FOOD FOR COMMUNITY, RELIEF FOR MOTHER EARTH

The crew does everything by hand–from planting seeds to pulling weeds to gathering the ripe crops come harvest time. “We don’t let machinery replace the value of the human being, but rather allow for the connection that needs to happen in what we call Sacred Space of those gardens,” says Ferguson. This also allows the community to abstain from the use of fossil fuels, instead opting for nature to provide everything needed to grow, cook, and store the food for the future.

A Tuscarora White Corn Plant grown in the gardens. It appeared as a sacred white plant, which is recognized as a visit from the spirit of the corn herself. Photo: Angela Ferguson

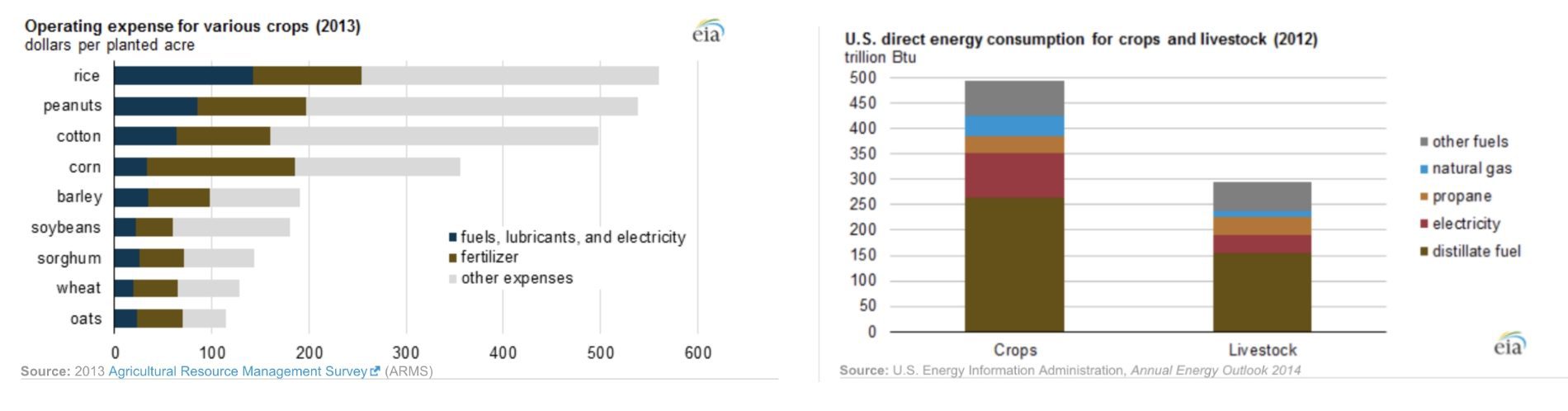

This traditional method of agriculture stands in stark contrast to the U.S. agriculture and food supply system today, which is highly dependent on non-renewable energy. As much as 16 percent of the total U.S. energy budget goes to food-related consumption, according to the USDA Economic Research Service. Second only to the energy sector, the agricultural industry is also the second largest emitter of greenhouse gases worldwide, according to the World Resource Institute (WRI). Over two-thirds of these emissions are from Methane produced by cattle and Nitrous Oxide produced during the extremely energy-intensive production of synthetic fertilizers, according to the WRI.

Operating Expense for Various Crops (2013) and U.S. Direct Energy Consumption for Crops and Livestock (2012) Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

By following their ancestral food propagation systems, the Onondaga Nation Farm Crew naturally addresses both problems. The community’s meat consumption is switching from packaged meat on the shelves to deer, turkey, rabbit, and fish, from hunts. Men in the community hunt what is in season based on traditional hunting cycles to prevent over-hunting. When the hunting season ends, their efforts are transferred toward fishing or joining women in the community to gather foods and medicines.

Thomas Benedict, a member of both the hunting and fishing crew, has been fishing for the nation since April of 2016 and just finished his first hunting season. “At the beginning of the season I didn’t know a lick about hunting, but by the end of the hunting season, I could confidently go out and get a deer, clean it, skin it, and distribute the meat, which I learned from listening, getting in there and learning, and asking questions,” says Benedict. “And what I’ve been taught I can pass on to the next group that comes in.”

Onondaga Nation hunters prepping deer. Photo: Angela Ferguson

Benedict is proud to be able to provide wild food to the community that is sustainably sourced, processed themselves, and healthier than the meats found on the grocery store shelves. “Giving the community the option to eat more naturally for free, giving an opportunity that people otherwise wouldn’t have; for me, that’s what it’s all about,” he says.

The community is also forgoing fertilizers and manure usage by using traditional methods of natural compost that includes utilizing fish guts left over from fishing, infrequently burning the fields, and using ash from cooking fires. Another part of their ability to forgo fertilizer usage comes from the natural symbiotic nature of the sacred Three Sisters.

THE THREE SISTERS

The Three Sisters–corn, beans, and squash–are planted in the Onondaga Nation gardens using a rotating crop system that naturally nourishes and replenishes the soil after the harvest. The crew plants the corn in one spot for three years, then rotates it out with the beans, and then squash before the team eventually plants the corn once more.

Corn consumes a lot of nitrogen as it grows, says Neil Patterson of the Haudenosaunee Environmental Task Force and Assistant Director at the Center for Native Peoples at SUNY-ESF. The beans and their nitrogen-fixing bacteria provide some additional nitrogen for the corn plant, while squash shades the ground, retaining water and creating a space that offers premium habitat for corn and beans. By using fertilizers, Patterson explains, there are three essential nutrients you’re trying to manage: Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Potassium. Companies make these fertilizers by breaking down petroleum into these essential nutrients, an extremely energy intensive process. This is where these bacteria on the nodules on the roots of beans come into play because they’re able to fix nitrogen in the soil that otherwise would not be available to corn.

Iroquois Strawberry Bush Bean Plant. Photo: Angela Ferguson

The Three Sisters are also significant to the Haudenosaunee because they were the first plants that Sky Woman, the Haudenosaunee Mother Goddess, had brought to them. The Three Sisters were traditionally planted all in one mound, supporting each other as they grew.

The mound of dirt represents a turtle’s back, Turtle Island. The corn plant is symbolized as the strong leader. It is the first to stand and holds everything else up. The beans then twist up and around the corn stalk, relying upon the strength of the corn. At the same time, they also protect the corn from toppling over when troubles arise such as the blowing winds. Following that comes the squash that acts like a scout on guard as it spreads its thorn-covered leaves around the garden floor. This helps to ward off animals and prevents the weeds from choking out the other plants.

Ferguson explained that the Three Sisters represent three types of people in a community that can support and protect one another just like corn, beans and squash. “We’ve learned from our elders to watch our gardens for signs of the struggles or strengths in our communities.” Is there trouble with the corn? Perhaps it is signifying trouble with community leadership. Is there trouble with the beans? Perhaps there is trouble with the community’s support for that leadership.

The Three Sisters were also chosen to be the staples of the Haudenosaunee diet because they provide all the main dietary components that people need, but the significance of these foods goes far beyond dietetics. “In our communities, food has always been considered medicine. When talking about our diet, there’s a complexity to that word that’s very different than what a colonized view of diet usually means, thinking about energetics specifically in a very linear, metabolic way,” says Patterson. “For the Haudenosaunee culture and belief system, there is a concept of our diet as a part of a food, medicine, and cultural complex, as well as an element of our fitness as planting and tending to the Three Sisters, expends a lot of energy.”

“Our communities are going through a renewal of experiencing the relationship between food, medicine, fitness, ceremonies, knowledge, and wisdom about the land that for a long time was not our highest priority because we were just trying to survive after colonization,” says Patterson. “Food sovereignty is a big part of the movement of resurgence in Indigenous communities. The Onondaga Nation’s support for these farm programs is part of the larger effort to regain our national sovereignty and self-determination in indigenous nations.”

Iroquois Wampum Dent Corn. Photo: Garet Bleir

Ivy Bennett, one of the members of the Farm Crew working in the gardens, has experienced this renewal directly. “I think I’ve grown as an indigenous person because we all know that we’re Native, but it’s different when you’re working with your indigenous food, taking care of it, and hoping it grows,” she says. “You feel a connection to your people while carrying on that tradition. This is what it means to be sovereign. We’re feeding ourselves and feeding our people.”

While the goal of most U.S. agriculture is primarily about the yield–deriving as much food as quickly as possible on as little space possible–for the Onondaga Nation, the goal is different. “For us, it’s how are the people going to benefit from that connection to the land and community. U.S. agriculture, due to the system that has been laid out, is based on a financial gain, but our agriculture is based on spiritual gain,” says Ferguson. “We want our foods not just to be great big, beautiful plants, but we want them to be nutritionally sound, with the most possible nutrients they could [hold] inside each and every seed that we’re feeding our people.”

Traditional varieties of heirloom corn have been diminished through years of genetic modifications that brought us the pale to light yellow varieties of sweet corn we see on the grocery store shelves today. European settlers first encountered the variety during a scorched-earth campaign against the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, according to The New York Times. After finding a field of extra-sweet corn with golden kernels, a lieutenant took some seeds to share with others. “Our old-fashioned sweet corn is a direct descendant of these spoils of war,” reads the article.

The modern varieties of sweet corn have an incredibly high sugar content and they contain less protein, beta-carotene and anthocyanins, which are responsible for the red, purple, and blue colors in fruits and vegetables, according to a report by the National Institute of Health. “Scientific studies…show that anthocyanidins and anthocyanins possess antioxidative and antimicrobial activities, improve visual and neurological health, and protect against various non-communicable diseases,” the report continues.

Many varieties of heirloom corn, such as the ones grown by the Farm Crew, are higher in nutritional value than their genetically modified counterparts. However, these varieties do not produce as many cobs per stalk. Since farmers are usually paid by the amount of corn they produce, not its nutritional value, the nationwide availability of heirloom corn is limited.

Onondaga Nation Farm Crew corn varieties. Photo: Garet Bleir

RECONNECTING

Cooking has also been a positive force for both the men and women in the community. “I want some of the young men in the community to see that it’s not women’s work to cook food or do certain activities,” says Ferguson. Historically, Onondaga men always made the soup and cooked the meat, but colonization imparted gender roles that altered this. “Traditionally in the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, when they saw that you had a talent for something, they would encourage you to move in that direction with your gift. It’s giving thanks to the creator for putting that gift in the person. So now we’re focusing on reconnecting in the kitchen as well.” After requests from the community, a variety of people are now helping to teach both traditional recipes as well as recipes from other indigenous nations, allowing the community to fully utilize the harvest with traditional meals. Ferguson and others have attended many food sovereignty summits with Indigenous Nations around the U.S. sharing each other’s recipes and bringing what they learn back to the Onondaga Nation.

ONONDAGA RECIPE: Three Sisters Corn Bread

- In small size saucepan, boil 1 cup Iroquois Cornbread Beans (or Iroquois Cranberry Beans) until tender, drain, then set aside.

- Begin boiling water in full 8-10 qt pot. Allow water to remain at rapid boil.

- Grind up 1 qt. Mohawk Yellow Flour into fine flour, (food processor or blender will do if traditional corn pounder is not available) and sift to remove any loose pieces, set sifted flour aside.

- Peel and dice one medium size (uncooked) Iroquois Crookneck Squash into small bite size pieces, (save the seeds!) & set aside.

- In large mixing bowl, add 2 cups of the sifted corn flour, 1 cup of diced squash, & 1 cup of beans.

- Mix dry ingredients with your hands to evenly distribute.

- Add 1 cup of boiling hot water to dry mixture and mix with wooden spoon. Mixture will be scalding hot! Be careful!

- Mold hot mixture with your hands into a firm ball to remove air pockets, then press down on wooden cutting board into a “wheel” shape rounding out the edges with your palms.

- Place wheel into pot of boiling water, it will sink to the bottom.

- When the wheel floats to the top, its done! Remove from water in one piece with wooden spatula or wooden corn bread utensil.

- Place cornbread on sheet of tin foil twice the size of the wheel.

- Wrap up in tin foil immediately so no moisture is released.

- Let stand for ten minutes.

- Unwrap tin foil then slice up wheel into half inch thick pieces and drizzle maple syrup over each individual serving.

- Enjoy & Share!

Ferguson sees what we now verbalize as food sovereignty, as a continuation of Onondaga cultural activities and instructions given to them since the time of creation. One of Ferguson’s primary motivations for this work has been witnessing a rise in health issues and loss of people across all indigenous communities, including the Onondaga Nation. “When there is a lack of participation in planting, foraging, hunting, and fishing in our communities, this is where we have seen alcoholism and drugs step in due in part to missing that sense of connection to the Earth, a duty to our people, or feeling a lack of purpose,” says Ferguson. Returning to who we traditionally are, to the activities and ceremonial and spiritual components that make up who we naturally fix many of the issues that society tries to repair reactively. People are willing to invest in repairing the effects of these issues through reactive governing, but “we want to reverse that and invest in the health of our nations before these problems take hold.”

Over the years, many people have come to Ferguson just wanting a job, without any spiritual connection to agriculture; but after working to produce food for the community, she has seen them make complete lifestyle changes, transitioning towards sober living, returning to ceremonies, coming back to the community, and returning to personal peace. “The first duty of every indigenous person across the whole turtle’s back, is to care for the land, the water, and all elements in our area, to give thanks for those, and to tend to the seeds given to us,” says Ferguson. “To watch people come back to that and grow into well-respected pillars of the community, that people go to for advice, friendship, laughter, and help has been amazing.”

Working in these gardens brings “that reconnection again in that sense of self, sense of belonging, sense of dignity, and the spiritual component of the relationship not only with the plants themselves, but with the Earth, your community, and the people you’re planting with,” says Ferguson. “It allows a person to realize where they fit in as a piece in the overall puzzle of our community.”

From revitalizing traditional food propagation, cooking, and distribution, to ensuring the seeds are there in the first place, the Onondaga Nation Farm Crew and Braiding the Sacred are taking significant steps to ensure food sovereignty is a reality for indigenous nations.

Follow Garet Bleir Journalism on Facebook or @GaretBleir on Instagram and Twitter

bookmarks Follow IC on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter

This article is a part of Food as Medicine, an exclusive series made possible by a grant from the Elna Vesara Ostern Fund.